How well does the average American understand basic Christian doctrine? For that matter, how about the average evangelical?

Perhaps not all that differently. And perhaps it matters how the questions are asked.

Reprising their ground-breaking study from two years ago, LifeWay Research and Ligonier Ministries released an update today on the state of American theology in 2016. Researchers surveyed 3,000 adults to measure their agreement with a set of 47 statements about Christian theology—everything from the divinity of Christ to the nature of salvation to the importance of regular church attendance.

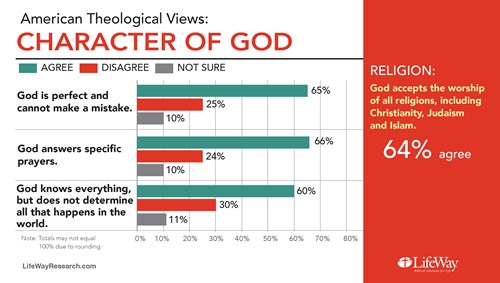

About two-thirds of Americans said that God accepts the worship of Christians, Jews, and Muslims (64%); around the same number agreed strongly or somewhat that there is one true God (69%), that he is perfect (65%), and that he still answers prayers (66%).

Of the 3,000 respondents, LifeWay identified 586 as evangelicals by belief: those who strongly agreed that the Bible is the highest authority for Christian belief; that personal evangelism is very important; that Jesus’ death on the cross was the only way to cancel the penalty of sin; and that trusting in Jesus is the only way to eternal salvation.

In the previous study, evangelicals identified themselves. The results revealed that they had a surprising level of confusion surrounding core Christian doctrine, including whether Jesus was fully divine, whether the Holy Spirit was a force or a personal being, and whether salvation depends on God or humans making the first move.

But this year’s study showed similar results, indicating that not only are those who self-identify as evangelical confused about the basic tenets of their faith, but so are those who fit the National Association of Evangelicals’s definition of evangelicals based on their stated beliefs.

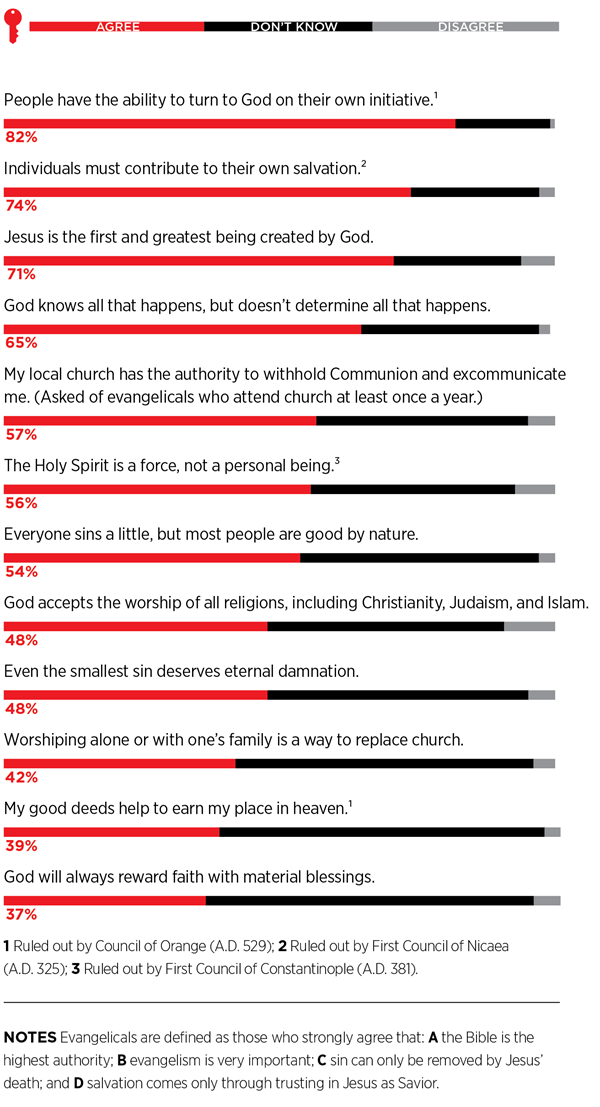

Here are the 12 questions where American evangelicals (as defined by belief) were most likely to deviate from traditional Christian orthodoxy—or at least demonstrate confusion over it—in 2016:

While virtually all of Americans with evangelical beliefs agreed that there is one true God in three persons (97%), that he is perfect (97%), and that he answers prayer (94%), respondents stumbled over the nature of Jesus. Seven out of 10 said he was the first and greatest being created by God (71%), an enormous jump over the 19 percent of self-identified evangelicals who agreed that Jesus was “the first creature created by God” last year.

The church largely settled the question of Jesus’ origin in A.D. 325 with the Nicene Creed, which states that Jesus is “begotten not made.” The belief that Jesus was created is called Arianism, named after the fourth-century priest Arius who argued from Bible verses such as John 3:16 and Colossians 1:15 that “there was a time when the son was not.”

But Timothy Larsen, professor of Christian thought at Wheaton College, said the fact that nearly three-quarters of evangelicals are confused about Jesus’ origin isn’t as dire as it sounds.

Evangelicals believe in “dramatic, life-changing adult conversions,” he said, and such conversions mean that new believers may have little training in the core tenets of their new faith.

“Much depends on how a question is phrased,” he said. “There is a lot in this survey which shows that the respondents are not even being internally consistent, but have been led to contradict themselves based on how the question sounded to them.”

Howard Snyder, visiting director of Manchester Wesley Research Center and former seminary professor, had similar reservations about the research. He said the confusing wording of the questions might actually falsely inflate the amount of heretical beliefs.

In fact, both Snyder and Larsen said they were impressed with the high percentage of orthodox agreement. Almost all evangelicals by belief said there is one God in three persons (97%), that Jesus rose physically from the dead (98%), and that the Bible is fully accurate in all it teaches (95%).

But they said they were disappointed with the confusion surrounding the Holy Spirit.

About the same number of evangelicals as the previous year (56%) said that “the Holy Spirit is a divine force but not a personal being,” and more than last year’s self-identified evangelicals (28% vs. 9%) believe “the Holy Spirit is a divine being, but is not equal with God the Father or Jesus.”

The beliefs that the Holy Spirit is an impersonal force and is not equal to the other two members of the Trinity were both condemned at the Council of Constantinople in 381, which generated additions to the original Nicene Creed to clarify the issue. The updated creed affirms the full divinity of the Spirit, and is the form of the creed most commonly recited in churches today.

“Clearly there is confusion about the nature and being of the Holy Spirit,” said Snyder, calling it “a theological concern.”

Beth Felker Jones, professor of theology at Wheaton College, agreed. The contemporary focus on “personal salvation” without always acknowledging the role of the Holy Spirit may have contributed to this confusion, she said.

“I’m surprised that people seem to know and affirm the formula for the doctrine of the Trinity, but aren’t able to connect that to the gospel truth that Jesus and the Spirit are truly and fully divine,” she said.

Consistent with the previous year’s findings is the confusion over the role of God’s grace in salvation. Four out of five evangelicals by belief (86%), more than last year’s self-identified evangelicals (71%), agreed that “a person obtains peace with God by first taking the initiative to seek God and then God responds with grace.”

Additionally, three out of four evangelicals by belief (74%, more than the previous year’s 56%) believe that “an individual must contribute his or her own effort for personal salvation.”

But a similar percentage (80%) also believe that “salvation always begins with God changing a person so that he or she will turn to him in faith,” indicating significant confusion about salvation.

The idea that people can choose God by the strength of their own will was taught by a fifth-century monk named Pelagius, who was a frequent theological opponent of Augustine. Pelagius’s beliefs were condemned at the councils of Carthage in 418 and Ephesus in 431, and a milder version of his beliefs was later rejected by the Council of Orange in 529.

While a person’s role in their own salvation is still a matter of debate among orthodox Christians today (such as the Calvinist vs. Arminian debates), Christians have historically affirmed that whatever role humans play in salvation is first and foremost a result of the work of the Holy Spirit in the life of the believer.

The seemingly contradictory responses from evangelicals to questions about grace and salvation may stem from contemporary culture, Snyder said. “The results show awareness that God alone by his grace provides salvation, but that salvation also involves ethical responsibility to put forth effort in seeking God.”

The results probably reflect the country’s “can do” mentality, he said.

In addition to questions from last year’s survey, LifeWay added new questions this year that shed light on how culture and evangelicalism interact.

MORE THAN ONE WAY TO GOD?

Though less than the general public (64%), nearly half of all evangelical respondents (48%) agreed that “God accepts the worship of all religions including Christianity, Judaism, and Islam,” showing a surprisingly pluralistic streak amongst an otherwise fairly conservative group.

This finding is striking primarily because all of those evangelical respondents also strongly agreed that “only those who trust in Jesus Christ alone as their Savior receive God’s free gift of eternal salvation.”

While the difference here could be a matter of wording (saying that God accepts the worship of all religions does not necessarily mean such worship leads to salvation), it still indicates an unexpected level of acceptance of other belief systems.

OPEN TO INTERPRETATION

Evangelicals were surprisingly relativistic as well, especially when it comes to the Bible. While all evangelical respondents strongly agreed that “the Bible is the highest authority for what I believe,” and nearly as many (95%) said “the Bible has the authority to tell us what we must do,” nearly a third (30%) believe that “the Bible was written for each person to interpret as he or she chooses.”

This could indicate that while evangelicals want the Bible to have the last word, they want the freedom to understand what that means in their own way.

Interpreting the Bible on an individual basis probably “sounds to a lot of [evangelicals] like the Protestant principle of the right of private judgment,” Larsen said. “It would take a series of questions to figure out what’s really going on here.”

WHO’S IN CHARGE?

While Christians have historically affirmed that the whole of history is in God’s hands and under his control, nearly two-thirds (65%) of evangelical respondents said that “God knows everything that occurs in the world but does not determine all that happens.”

The response reflects the recent debates about the meticulous sovereignty of God, spurred by natural disasters, humanitarian crises, and wars that can lead Christians to wonder if they are part of God’s plan. Some reconcile the seeming disconnect between a good God and a suffering world by arguing that God is not in direct control of all that is happening and allows the free will of human beings to determine, in part, the direction of history.

A few of these views, such as open theism and process theology, are still being actively debated by Christian thinkers, and the unresolved status of the discussion is reflected in the broader evangelical public.

Some of this straying from traditional Christian beliefs may stem from the fact that nearly a quarter of evangelicals believe that “there is little value” in “studying or reciting historical Christian creeds and confessions” (23%). Another 9 percent said they weren’t sure, the second-highest level of uncertainty across all questions.

While a plurality agree that historic creeds and confessions are important, if one in four evangelicals doesn’t see the point in studying the defining documents of the faith, perhaps it is not surprising that evangelicals are confused about what Christians believe.

LifeWay also asked evangelicals about their views on church and the Bible. Respondents were surprisingly apathetic about church attendance, given that three-quarters of them attend at least once or twice a month. Two out of five believe that “worshipping alone or with family is a valid replacement for regularly attending church” (42%).

Probably as a reflection of American culture, evangelicals’ views on church authority indicate a preference for autonomous individualized faith. Nearly three in five evangelicals think that the local church should not have “the authority to withhold the Lord’s Supper from me and exclude me from the fellowship of the church” (57%), and more than two in five said that “the church should be silent on issues of politics” (46%).

Evangelicals also wavered a bit on the authority of the Bible. While 95 percent agreed that “the Bible is 100 percent accurate in all it teaches,” 17 percent also thought that “the Bible, like all sacred writings, contains helpful accounts of ancient myths but is not literally true,” and 4 percent weren’t sure.

More than half of all evangelicals either believe that “modern science discredits the claims of Christianity” (45%) or aren’t sure if it does or doesn’t (11%).

Snyder blamed the overall lack of orthodoxy on the fact that “most evangelicals churches have largely abandoned catechesis (or a functional equivalent). ... Theologically informed discipleship is mostly absent from churches.”

“The survey underscores our desperate need for sound doctrinal teaching in the local church,” agreed Jones. “I fear that we’re spending too much time in cults of personality around charismatic superstar pastors, who often focus more on their personal theological idiosyncrasies and pet ideas than on basic Christian orthodoxy.”

She found the results of the survey to be a call to action: “People are hungry for orthodoxy. Church leaders need to feed them.”

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month