You’ve heard the buzz: A Wrinkle in Time, based on the classic children’s book by Madeleine L’Engle (1918–2007), hits theaters this week as a 0 million Disney movie.

A lot more than money is riding on the film’s success. Not only is the sci-fi novel beloved by millions of readers—since winning the 1963 Newbery Medal, it has sold upwards of 16 million copies—but its author was one of the most adored writers of Christian faith in recent history.

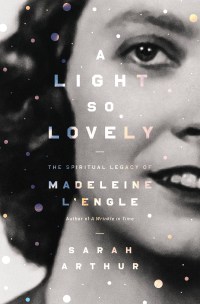

As I’ve learned while writing her spiritual biography (A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle, which releases in August), her fans among millennials and my own Generation X, in particular, are as vast as the cosmos she so loved. For many who struggle with faith and doubt, L’Engle has become a kind of patron saint for the wavering, the wondering, and the wounded.

No pressure, Hollywood.

This new adaptation of Wrinkle, directed by the irrepressible Ava DuVernay (Selma, 13th, Queen Sugar), stars no less than Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling, and Chris Pine. Frozen’s Jennifer Lee adapted the storyline for the screen, and along the way the main characters have been creatively recast as a multiracial family. DuVernay herself is the first female director of color to oversee a budget this size.

Newcomer Storm Reid plays Meg Murry, the story’s teen protagonist, who is sent by a triad of angelic beings (Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which) on a quest to find her missing scientist-father trapped behind a dark force in the universe. The “Mrs” trio teaches Meg and her companions how to fold, or wrinkle, the space-time continuum so they can skip from galaxy to galaxy, planet to planet—a concept called tessering.

“I think you have to prepare yourself that the movie will look different than the book,” producer Catherine Hand told me. “I hope people who love the book don’t just focus on the trees and not see the forest.” Hand first sat down with L’Engle in 1979 to discuss bringing the story to the big screen and now, nearly 40 years later, is seeing her dream become reality. “The movie is going to look different because it had to look different,” Hand explained. “Too many filmmakers, writers, directors, all sorts of creative talent have been influenced by Wrinkle for 50 years. Some of the visuals that we hold dear in Wrinkle we’ve already seen on film. We had to take the essence of the emotional story—e.g., why did this happen in the book?—and explore how to give it a new look but with the same meaning.”

The question many are wondering is whether the “essence” and “meaning” will include the spiritual themes that were vital to L’Engle’s Christian faith.

Asking ‘Cosmic Questions’

During the 1950s, as a 30-something transplant from New York City to rural Connecticut, L’Engle struggled to balance writing, child-rearing, and small-town life. She also wrestled with what she called “cosmic questions”: Does God exist? Why are we here? Do we exist after death? Well-meaning pastors encouraged her to read German theologians (she rarely ever named which ones, exactly, although philosopher Immanuel Kant is a strong contender). But she found no solace there. Such theology, for L’Engle, emphasized a limited God definable by human categories, a concept wholly at odds with the awe-inspiring, star-strewn universe she saw at night while walking her dogs.

By contrast, it was the wonder and humility of scientists, especially theoretical physicists like Max Planck and Albert Einstein, who eventually convinced her to become a Christian. If the Creator of a vast and surprising cosmos could love this small planet enough to become one of us, then—despite her ongoing questions—that was a faith worth clinging to. As L’Engle said in a 1979 interview with Christianity Today, “I believe that we can understand cosmic questions only through particulars. I can understand God only through one specific particular, the incarnation of Jesus of Nazareth.”

Thus, “A Wrinkle in Time was my rebuttal to the German theologians,” L’Engle wrote in Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (1980). Her protagonist—angry, nerdy Meg Murry, in many ways a portrait of L’Engle herself as a girl—is unwilling and unable to conform to cultural expectations, to the usual categories by which we define human worth. By the end of her story, Meg must confront the source of the darkness that’s at war with the light: a pulsing, disembodied brain that threatens to absorb everything into the pattern of itself. Its goal is to annihilate the created particularity of each unique thing, down to the smallest particle.

For anyone who’s ever fallen asleep reading German theology (raises hand), this is a stirring concept. If faith can be reduced to an intellectual exercise, to mere agreement with certain principles and precepts, then all you have left is knowledge without agency, without mercy or compassion. All you have is a disembodied mind, out there in the universe, coldly detached from human suffering. And a thing without a body could never, ever love you the way God in Christ does.

Translating a ‘Core Story’

One could argue that Wrinkle is a “core story” in American literature: one of those seminal classics that takes on the status of myth. Myth’s essential nature is to articulate truths about the human experience that are universal, that are beyond mere human invention, pointing to a pattern of meaning that undergirds our existence. For literary-minded Christians like C. S. Lewis (The Chronicles of Narnia), myths offer partial glimpses of a foundational Story written by the Author of all authors, a Story that became historical fact in Jesus. Myths may not be about what literally happened, but they are most certainly about what happens: birth, joy, passion, longing, loss, death, redemption.

Meg’s journey to fight not only the darkness “out there” but to fight it within herself is one such story. Indeed, I would argue that Wrinkle qualifies as “mythopoeic”: a term Lewis and his friend J. R. R. Tolkien (The Lord of the Rings) used to describe a created thing that is somehow more than itself, whose spiritual and theological underpinnings are able to transcend the original storyteller and context.

Lisa Ann Cockrel, director of Calvin College’s Festival of Faith and Writing, was a college student when she saw Wrinkle performed as a stage play at the Lifeline Theatre on Chicago’s North Side. “It was my first really powerful, personal engagement with Madeleine’s work,” she said. “I can’t even describe it to you, the stagecraft of how they managed to pull off a tesser. It was magic, magic, from what I can tell.” Just one example of how the truly mythopoeic can transcend even the medium by which it comes to us, whether children’s book, stage performance, opera, graphic novel, or, one hopes, a blockbuster movie.

During a Q&A at the 1996 writing festival, L’Engle was asked about a possible film version of Wrinkle. She claimed she had told Catherine Hand, “I can’t sign the average Hollywood contract because I cannot sign that clause giving the producer freedom to change character and theme.” L’Engle explained that she eventually got the clause reversed, but the contract also included language granting the producers the rights to the movie “in perpetuity throughout the universe.” So, she said, she took a red pen and made an asterisk, noting, “With the exception of Sagittarius and the Andromeda Galaxy.” As the festival audience erupted in laughter, L’Engle joked, “They had a serious meeting of their lawyers before they would accept this, in case I knew something they didn’t know.”

Then, in a more earnest tone, she continued: “I would like it to be made into a movie, but a good movie, not a bad one. I believe my books, and so I can’t sign that clause. And I’d rather not have them done than have them come out and say something I’m not saying, which is very easy in the world of Hollywood.”

Only after various fits and starts, a low-budget, made-for-TV movie finally aired in 2004 that was panned by reviewers for its clunky special effects and slow pace. It also notably left out both a key biblical text (John 1:5) and a direct reference to Jesus that together distill a vital spiritual theme in the book: the source of the light by which the darkness is overcome is not we ourselves—though we’re invited to join it. Yes, Jesus told his followers “you are the light of the world” (Matt. 5:14), but only because they participate in the light of Christ that “shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:5). (For the record, this particular viewer wept openly when Mrs. Whatsit, before taking leave of the Murrys in the final scene, told Meg, “Well done.” Three out of five stars.) But anyone who loves the book was left wanting more.

Despite ongoing obstacles, Hand didn’t give up her quest to bring the film to the silver screen. It’s a big story, after all—galaxy-jumping is no trifle and deserves big effects. But its themes are also, as Hand is well aware, cosmic. “My curiosity about a spiritual life absolutely was one of the driving forces behind why I did what I did for 30 years,” she told me. “When I was a young girl, my mother said, I used to wake her up in the morning around five to make sure we weren’t late for church. So there must’ve been something in me that was always drawn to faith.” She went on to say, “I think I had an understanding of what God was from a 10-year-old point of view, which deepened when I got to know Madeleine, who expanded my views.”

The two developed a friendship over the decades, one that Hand treasures. “There is no one on this planet that loves A Wrinkle in Time more than I,” she said. “However, we had to make a movie of the book, which meant we had to rethink the story. Jennifer Lee, Ava DuVernay, the creative team at Disney, and Jim Whitaker, the other producer, were essential in finding a fresh approach to the material. We all loved the themes, the characters—the essence of the story. And I hope audiences will agree that we stayed true to that essence.”

Entertaining Possibilities

Of course, insert Oprah into any story, and it will mean whatever Oprah wants it to mean. But does it retain its mythopoeic nature as a story with theological underpinnings? And does that matter?

“When it was announced that Ava DuVernay was going to do the adaptation, I was so excited,” YA author Sara Zarr told me, “because I felt that Selma [DuVernay’s film about the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama] had a really strong directorial point of view. And that’s what you need when you’re taking on a story that’s so well known. Because if you don’t have your own strong point of view and confidence in executing it, you’re going to try to make it into something that everyone will like or approve of, maybe in a tepid way, and no one will criticize.”

Zarr’s own Story of a Girl was made into a television movie starring Kevin Bacon and Ryann Shane, and the process of watching her own book become film was a fascinating one. “When I’m writing a book,” she said, “I may or may not have an idea in my head of what a character looks like, and I may or may not do a decent job of describing that.” Then the reader gets a hold of the book, and “they’re recreating the image in their head, and it’s going to come together differently than in someone else’s head. So when we’re reading a novel, we’re recreating a story.” When it comes to a film adaptation, “we have to go in realizing not every single person in the world sees or experiences things in the same way we do. And I think that’s really cool.”

Film critic and novelist Jeffrey Overstreet (Auralia’s Colors) agrees: “I hope that there’s still that sense of expansiveness in all the story means,” he told me. “Anytime you adapt a story like this from one medium to another, from one translation to another, you’re going to end up entertaining possibilities that were just suggested in the original and thus also inevitably minimizing things that are emphasized in the original. That’s just the nature of adaptation. It’s sort of like an illustrated manuscript among many illustrated versions of the same thing.”

Zarr added, “If an adaptation is not how they imagined it, fans can feel it’s a defilement of the original thing. But the original thing will always still exist.” And it’s not going away anytime soon: As of this writing, L’Engle’s book is sitting at number one on Amazon’s current bestsellers list.

“Madeleine would want us to go to the movie with an open mind and a willing heart,” Hand told me, “because that’s how she saw the universe.”

It remains to be seen whether the film will qualify as mythopoeic, theologically speaking. It may not address all our “cosmic questions.” But it can still be darn good fun.

Sarah Arthur is the author of a dozen books about the intersection of faith and literature, including the forthcoming A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle (Zondervan).