Scientists claim they have discovered the Higgs boson, also called the "God particle," that could help explain what gives all matter in the universe size and shape.

Scottish physicist Peter Higgs and other scientists predicted in the 1960s that particles interact with one subatomic particle, called the Higgs boson or the "God Particle." Scientists are calling the discovery "Higgslike," a key to understanding why there is diversity and life in the universe, according to The New York Times.

Higgs has said he objected to the "God particle" label because he "worries that the title 'might offend people who are religious.'" The 2008 interview with New Scientist (registration required) does not explain what he feels might be offensive about the connection, whether there was something inherently contradictory between what scientists believe to be the universe's origins with what those who are religious would believe, connected specifically to the boson. A similar idea was repeated in The Guardian, linking the term to another physicist, who intended something completely different for the name.

Its theistic nickname was coined by Nobel-prize winning physicist Leon Lederman, but Higgs himself is no fan of the label. "I find it embarrassing because, though I'm not a believer myself, I think it is the kind of misuse of terminology which I think might offend some people."

It wasn't even Lederman's choice. "He wanted to refer to it as that '[g–d–-] particle' and his editor wouldn't let him," says Higgs.

Lederman's own book The God Particle uses the same line

This boson is so central to the state of physics today, so crucial to our final understanding of the structure of matter, yet to elusive, that I have given it a nickname: The God Particle. Why God Particle? Two reasons. One, the publisher wouldn't let us call it the [G–d–-] Particle, though that might be a more appropriate title, given its villainous nature and the expense it is causing. And two, there is a connection, of sorts, to another book, a much older one…

And then he writes about the story of the Tower of Babel and the "curious intellectual stress" it illustrates.

In an interview with NPR, Victoria Martin, a lecturer in physics and astronomy at the University of Edinburgh and a former student of Higgs, explained why scientists don't like the "God Particle" term.

SIEGEL: I want to ask you about this particle's nickname, the "God particle." What did Higgs, who've I've read is an atheist, think about the nickname the "God particle"?

MARTIN: I'm sure - I actually haven't ever asked him this directly, but I'm sure he doesn't like it. Almost all particle physicists detest that name. ...

So the name stuck and I think it's fine because then people know what we're talking about. But secretly, all of us hate the name, the "God particle."

Science writer Dennis Overbye, who covered Wednesday's news, wrote a fascinating essay for the New York Times in 2007 on the challenge of inserting (or not inserting) God into science writing, particularly when writing about the "God Particle."

Last week a reader accused me of trying to attract religiously inclined readers by throwing out "God meat" for them.

It was not the first time that I had been accused of using religion to sell science. Or was it using science to sell religion?

...My guide in all of this, of course, the biggest name-dropper in science, is Albert Einstein, who mentioned God often enough that one could imagine he and the "Old One" had a standing date for coffee or tennis. To wit: "The Lord is subtle, but malicious he is not."

...I wouldn't dream of depriving any future Einstein of his or her rhetorical or metaphorical tools.

Here's how the Associated Press explains the scientific discovery.

The Higgs boson, which until now has been a theoretical particle, is seen as the key to understanding why matter has mass, which combines with gravity to give an object weight. The idea is much like gravity and Isaac Newton's discovery of it: Gravity was there all the time before Newton explained it. But now scientists have seen something very much like the Higgs boson and can put that knowledge to further use.

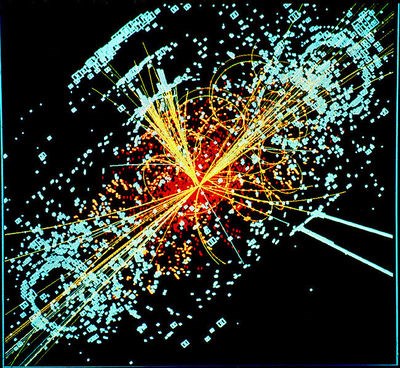

CERN's atom smasher, the $10 billion Large Hadron Collider on the Swiss-French border, has been creating high-energy collisions of protons to investigate dark matter, antimatter and the creation of the universe, which many theorize occurred in a massive explosion known as the Big Bang.

A Sydney Morning Herald piece collects the jokes:

A Higgs boson walks into a church, according to one joke which did the rounds.

"We don't allow Higgs bosons in here!" shouts the priest.

"But without me, how can you have mass?" asks the particle.

The Christianity Today July/August cover story will be on "The Tale of Two Scientists: They agree about the scientific method—but not about what happened 'in the beginning.'"

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month