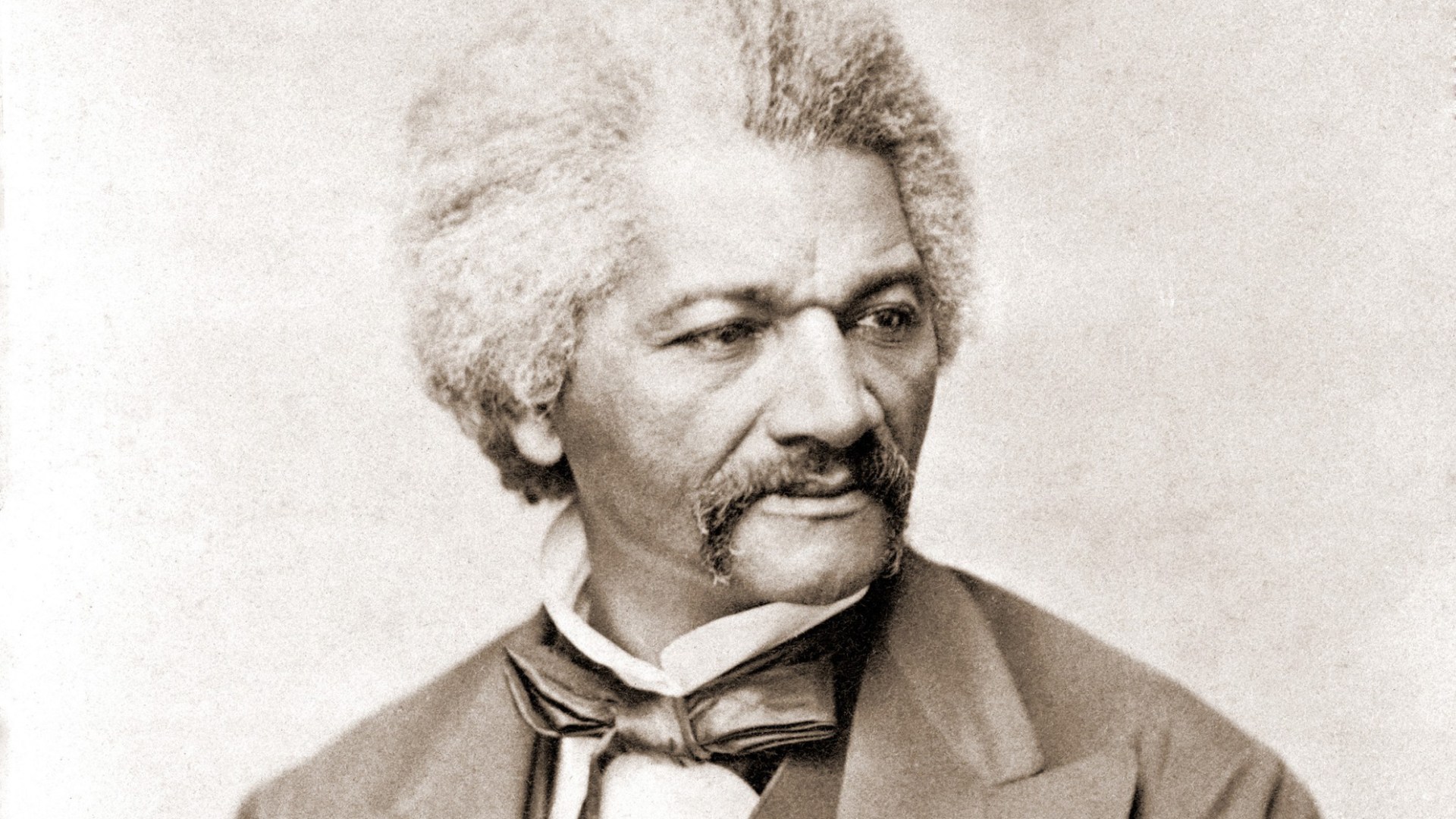

Frederick Douglass might be called the Barack Obama of the early 19th century—a figure who revolutionized expectations of black people simply by being himself. A brilliant writer, thinker, and orator, Douglass repeatedly confounded both friends and critics. They found it hard to believe a self-taught former slave could engage as an equal with the intellectual leaders of his day.

Douglass was born as a slave in rural Maryland in about 1817, though the date of his birth went unrecorded. He never knew his father, and his mother died when he was a boy. Early on, according to his own recollections, Douglass felt the pain of being enslaved for life and longed for freedom. Sent to Baltimore by his master, he managed to teach himself to read and write while earning money for his master as a laborer on the docks. In 1838, probably just out of his teens, he escaped to the North. Arriving in New Bedford, Massachusetts, Douglass joined the local anti-slavery association, was eventually "discovered" as an eloquent abolitionist, and began to make speeches throughout the North.

Douglass's first autobiography, published in 1845, was Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. It was so well written many critics doubted that he had written it himself. In 1847 he moved to Rochester, New York, to start his own newspaper, The North Star. Through his writings and lectures he became a major contributor to the abolitionist movement. Douglass was also one of the first to support the woman's rights movement, attending and speaking at its first convention in Seneca Falls, New York.

As the following excerpts from his writings show, Christianity and Christian ethics shaped Douglass's thinking—both the positive example of love for all people he learned in his reading of the Bible, and the hypocrisy he often excoriated in his description of slaveholders' piety.

I was not more than thirteen years old, when I felt the need of God, as a father and protector. My religious nature was awakened by the preaching of a white Methodist minister, named Hanson. He thought that all men, great and small, bond and free, were sinners in the sight of God; that they were, by nature, rebels against His government; and that they must repent of their sins, and be reconciled to God, through Christ. … I was, for weeks, a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through the darkness and misery of doubts and fears. I finally found that change of heart which comes by "casting all one's care" upon God, and by having faith in Jesus Christ, as the Redeemer, Friend, and Savior of those who diligently seek him.

After this, I saw the world in a new light. … I loved all mankind—slaveholders not excepted; though I abhorred slavery more than ever.

I became acquainted with a good old colored man, named Lawson. A more devout man than he, I never saw. He drove a dray for Mr. James Ransey, the owner of a rope-walk on Fell's Point, Baltimore. This man not only prayed three times a day, but he prayed as he walked through the streets, at his work—on his dray—everywhere. His life was a life of prayer, and his words, (when he spoke to his friend,) were about a better world. … Becoming deeply attached to the old man, I went often with him to prayer-meeting, and spent much of my leisure time with him on Sunday. The old man could read a little, and I was a great help to him, in making out the hard words, for I was a better reader than he. I could teach him "the letter," but he could teach me "the spirit;" and high, refreshing times we had together, in singing, praying and glorifying God.

The good old man had told me, that the "Lord had a great work for me to do;" and I must prepare to do it; and that he had been shown that I must preach the gospel. His words made a deep impression on my mind, and I verily felt that some such work was before me, though I could not see how I should ever engage in its performance. "The good Lord," he said, "would bring it to pass in his own good time," and that I must go on reading and studying the scriptures … . When I would say to him, "How can these things be—and what can I do?" his simple reply was, "Trust in the Lord." When I told him that "I was a slave, and a slave for life," he said, "the Lord can make you free, my dear. All things are possible with him, only have faith in God." "Ask, and it shall be given." "If you want liberty," said the good old man, "ask the Lord for it, in faith, and he will give it to you."

— From My Bondage and My Freedom, 1846

But you will ask me, can these things be possible in a land professing Christianity? Yes, they are so; and this is not the worst. … I have to inform you that the religion of the southern states, at this time, is the great supporter, the great sanctioner of the bloody atrocities to which I have referred. While America is printing tracts and bibles; sending missionaries abroad to convert the heathen; expending her money in various ways for the promotion of the gospel in foreign lands—the slave not only lies forgotten, uncared for, but is trampled underfoot by the very churches of the land. What have we in America? Why, we have slavery made part of the religion of the land. Yes, the pulpit there stands up as the great defender of this cursed institution, as it is called. Ministers of religion come forward and torture the hallowed pages of inspired wisdom to sanction the bloody deed. … I have found it difficult to speak on this matter without persons coming forward and saying, "Douglass, are you not afraid of injuring the cause of Christ? You do not desire to do so, we know; but are you not undermining religion?" This has been said to me again and again … but I cannot be induced to leave off these exposures. I love the religion of our blessed Savior. … It is because I love this religion that I hate the slaveholding, the woman-whipping, the mind-darkening, the soul-destroying religion that exists in the southern states of America.

—From Reception Speech at Finsbury Chapel, Moorfields, England, May 12, 1846

Copyright © 2008 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History & Biography magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History & Biography.