In this series

“High King of heaven, my victory won

May I reach heaven’s joys, O bright heaven’s sun!

Heart of my own heart, whatever befall,

Still be my vision, O Ruler of all.”

With these words, the ancient Irish poet brings us into a different world. It is a world where God is not just the omniscient, omnibenevolent deity of scholastic logic, but the “high King of heaven.” This title moves the mind back through time to a different political moment, a time when security rested not in democratic freedoms but in the local king submitting to the high king in his hall. The poet reaches for the political structure of ancient Ireland to describe the spiritual relationship of Christians. Just as the local king ruled his kingdom under the authority of the high king, so each Christian man and woman becomes a king or queen ruling creation under the benevolent grace of our Father.

In Poetics, Aristotle describes the goal of poetry as mimesis, imitation. The poet seeks to artfully construct a sort of mirror reflecting reality back to his audience. It is in this sense that Christian theology is a poetic, or perhaps mimetic, discipline. Theology is not necessarily creative but seeks to reflect the work of God back to the current generation of Christians. Just as the poets of ancient Greece reflected their historical context, so, too, Christian theologians bring their own historical moment into the task of writing theology.

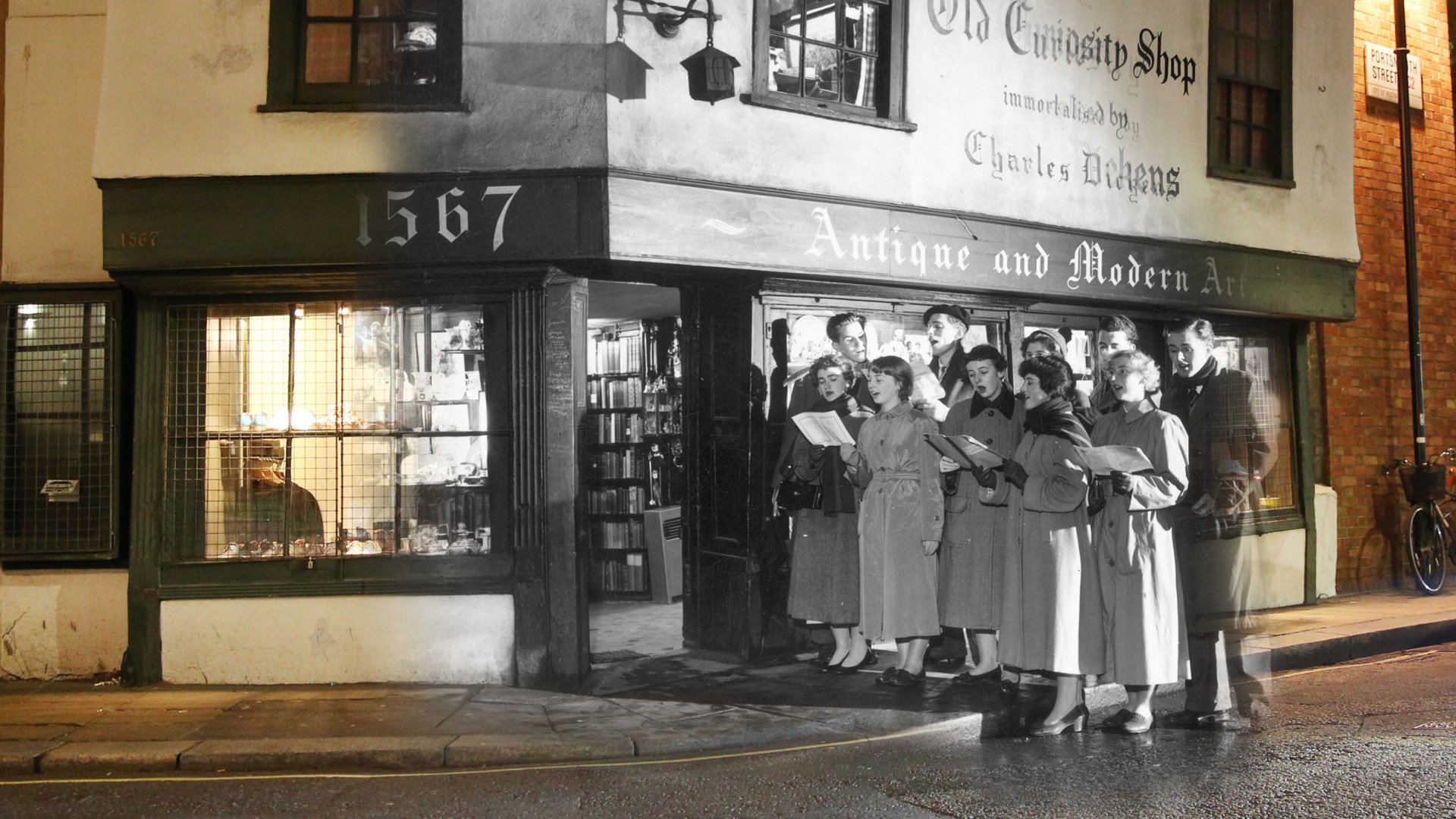

In the genre of Christmas hymns, we can see commonality as medieval, modern, and contemporary hymn writers draw on both the gospel accounts of Christ’s birth and the political and theological categories of their day to shape their hymns. By increasing our awareness of the riches available in the hymnic tradition, we deepen our worship through a new perspective and we demonstrate the chronological unity of Christ’s church.

Vassals in the Kingdom of God

The Middle Ages is a fascinating time period including the fall of Rome, the rise of European states, the spread of monarchy, the birth of the university, and the nearly universal practice of Christianity. Throughout the Middle Ages (approximately 476–1492), Christianity provided the impetus for national and international unity. Through the work of missionaries like Patrick, Columba, Boniface, Augustine of Canterbury, and countless others, the Christian faith spread throughout Europe, reaching a point of cultural saturation unimaginable today.

Politically, kingdoms tended to be small and were ruled by powerful warlords commanding personal loyalty. The vast majority of Europeans lived in extreme poverty as serfs. Education was sparse, concentrated in the monastic hall; medical knowledge was mostly wrong, leaving peasants without recourse when plague struck. Farming served as the nearly universal occupation, with most families being but a single failed harvest away from starvation.

In this historical period, Christianity thrived. Faithful people passed on the truths of the gospel, and several hymns from this millennium still resonate with contemporary audiences. One of these hymns emerges from the halls of the past each Christmas season.

“Good Christian Men Rejoice” dates to the 14th century and comes from a Latin and German origin. The more popularly known traditional English version of “Good Christian Men Rejoice” reflects substantial evolution throughout the centuries; the 14th-century translation illustrates both a physical understanding of heaven and a feudal soteriology. Henry Suso rendered the third verse as “Where are joys? / Nowhere more than there / Where angels sing / New songs / And the bells ring / In the courts of the King. / Oh, were we only there!” In these lines, heaven is described in terms of physical sounds connoting joy and location: Angels “sing,” bells “ring,” which we could hear if we were physically present in the king’s “courts.” Heaven has not only sounds to be heard, but also an existence as a court ruled by the benevolent lord and filled with his faithful vassals. The verse ends with a sense of longing—“Oh, were we only there!” which conveys the hope of achieving entry as vassals into this wondrous court.

This language reflects the recent (within the 11th and 12th centuries) impetus toward crusade. In 1095, Pope Urban II proclaimed the necessity for all good Christians to journey to Jerusalem to regain the Holy City. By the second Crusade, Bernard of Clairvaux used the language of regaining Jesus’ kingdom, viewing Christ as a feudal lord: “The earth trembles and is shaken because the King of Heaven has lost his land, the land where once he walked. … I tell you, the Lord is testing you.” The vision of heaven as a physical destination (a court analogous to an earthly king’s court), which the faithful should hope to gain because of Christ’s victory on the cross, provides a window into how medieval Christians related to God.

From boisterous angels to a silent night

Medieval hymns like “Good Christian Men Rejoice” cast the work of salvation in the model of feudal relations; 18th- and 19th-century hymns employed different motifs drawn from different eras. By the 18th century, the era of exploration had resulted in a wider world traversed by international commerce. The development of the scientific method and its application altered the very view of the solar system; the Enlightenment fostered a greater focus on the individual and his or her capacity for reason.

Politically, monarchy was the traditional paradigm in Europe during this period, with general acceptance of the body politic theory. This metaphor envisioned society as a body with each social class corresponding to hands, heart, feet, and so on. The king as the head (or heart depending on the theorist) provided unity and a focal point for loyalty. Hymns in the 18th century, as represented in the work of Charles Wesley, came into their own as a vehicle for teaching complex theology to literate laymen. Brother to John Wesley, Charles was a gifted poet and wrote hundreds of hymns over his lifetime.

One of Wesley’s most famous Christmas hymns, “Hark the Herald Angels Sing” contains echoes of “Good Christian Men Rejoice” in that it recalls the events in Luke 2 and summons the hymn singers to join with the angels in rejoicing. Its uniqueness begins with Wesley’s description of the “newborn king.” This King is the reason all nations should “rise [and] join the chorus of the skies;” he is the “everlasting Lord.” This perfect King who frees from death is King over all nations and will bring “peace on earth and mercy mild.”

In contrast to absolutist kings (Louis XIV in France and Charles I in England), the ruler Wesley describes is a King who has laid “his glory by.” Additionally, Wesley locates reconciliation between “God and sinners” here on earth; salvation is not something to win or reach, but it begins here. This 18th-century hymn lacks the idea of escaping the horrors of the world; instead, the world becomes the place where God’s redemption begins.

Wesley illustrates a more positive theology of the world. Alongside his more famous brother John, Charles Wesley helped develop a Methodist form of Christianity combining the more democratic movements of the 18th century with hierarchical elements of Anglican practice, eventually resulting in a flourishing expression of Christianity which spread throughout the world.

A century later, the political context had shifted wildly. By the early 19th century the chaos of the French Revolution and Napoleonic era had given way to the new commercial opportunities of the Industrial Revolution. The missionary movement was underway, which paired with the growth of the British Empire. In America, the 19th century was marked by political upheaval culminating in the American Civil War to determine the questions of dissolving the federal union and slavery. It was a tumultuous, chaotic time marked by expanding technology but shrinking consensus in how people should live together in political society.

In that context, Austrian Roman Catholic priest Joseph Mohr and organist Franz Gruber first performed their new hymn “Stille Nacht” in 1818, later translated into English as “Silent Night.” In contrast to the chaos of life in 1818 Bavaria (Napoleonic Wars; the growing dominance of Prussia; competing nationalism, liberalism, and conservatism), Mohr depicted a “silent night / Holy night” perhaps intentionally putting together two qualities fading from his world: silence and holiness.

Mohr’s description of the infant Christ is also striking: “tender and mild” with “radiant beams from thy holy face” and “Jesus, Lord at thy birth!” Here is a Christology combining kindness with lordship and borrowing the language of light to convey divinity.

Rather than the king who won entrance into his court for his vassals or the king heralded by the mighty angels in the sky, this hymn envisions one who is “lord” at birth but filled with tender kindness alone. The political framework to support a vision of kingship as a gloriously good thing had shifted. In contrast to previous eras, Mohr’s hymn reflects a weaker image of Jesus as the ruling Lord who enters his creation in quiet and awe.

The contemporary “wondrous mystery”

The contemporary theological imagination has been shaped by the inerrancy debates brought on by the fundamentalism/modernism divide in the 20th century. The 21st century has been called both “post-Christian” and an era recovering the importance of religious truth. Multiculturalism has become normative in large sections of Western civilization; materially, the Western world stands at an unprecedented level of prosperity. Militarily, we have lived with the capacity for nuclear devastation since 1945 but have yet to destroy the world.

Postmodern philosophy has played a significant role in shaping thought and bringing to light the lack of consensus on fundamental questions. Within the church, these realities have encouraged many denominations to recover the resources history offers them in terms of creeds, councils, and habits of life.

Matt Papa’s song “Come Behold the Wondrous Mystery” encapsulates these historical realities in his approach to writing a 21st-century Christmas hymn. Rather than modernism’s attempt to reconcile science and theology, Papa calls the divine work the “wondrous mystery” which it is our task to “come behold.” This Christ is no mewling babe but a King who dawns powerfully like the sun.

This hymn celebrates not just the “silent night” of birth, but the whole life, death, and resurrection. Papa ventures into the Pauline epistles (particularly Romans) to write, “See the true and better Adam / Come to save the hell-bound man.” He looks backward to the Old Testament to claim “Christ the great and sure fulfillment / Of the law; in Him we stand.” This Christ’s victory is not in his birth, but in death: “Christ the Lord upon the tree / In the stead of ruined sinners / Hangs the lamb in victory.” This Christmas hymn concludes as several others do, with the promise of resurrection purchased through birth and death:

Come behold the wondrous mystery

Slain by death the God of life

But no grave could e’er restrain Him

Praise the Lord; He is alive!

What a foretaste of deliverance

How unwavering our hope

Christ in power resurrected

As we will be when he comes.

Here Jesus not only opens the door to the courts of heaven, nor is he merely an avenue for the nations to be ruled in peace, he also provides hope for all mankind. Matt Papa demonstrates a desire in the contemporary theological imagination to show Christ as the center of Scripture, the hope of all mankind, and the ultimate mystery worth studying.

Worshiping with the saints throughout the ages

Christianity is a historical faith, rooted in the temporal reality of the birth, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus. Because of this historicity, the way theologians write about the faith is shaped by their historical moment. When we assemble a list of hymns and songs for corporate worship, we are drawing together different ways of looking at the world from across the ages. Just as we might play certain choruses mixed with certain traditional hymns to draw a physical congregation together, when we mix hymns from across the ages we draw together spiritually with those saints who have passed on to glory.

This chronological awareness becomes one way to demonstrate the unity of the church across the ages. The picture of Revelation 7:9–12 shows the church gathered across all of time and space; there will be medieval Catholics seeing in Christ the fulfillment of their monarchical vision worshiping next to moderns with their democratic ideals beside postmodern Christians marveling at the great mystery.

As we incorporate different historical imaginations into our earthly worship, we prepare to commune with our brothers and sisters from different historical moments in the coming eternity. Such an approach, whether we realize it or not, demonstrates the diversity of approaches in Christology.

Christ as God is infinite, and poetic attempts to express the inexpressible illustrate the marvelous complexity of the Godhead. When we sing “Be Thou My Vision,” recognizing the meaning of the “high King of heaven” recalls relationships of loyalty, gratitude, and wonder which brings glory to God and joy to the world. We are his people, the redeemed sheep of his pasture, and as such we call him “Ruler of all.”

Josh Herring is a humanities instructor at Thales Academy, a graduate of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and Hillsdale College, and a doctoral student in Faulkner University’s Great Books program. He has written for Moral Apologetics, The Imaginative Conservative, Think Christian, and The Federalist.