In this series

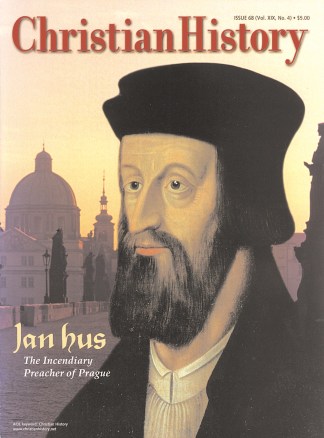

Jan Hus has always been difficult to place precisely in the history of Christian thought. Does he belong to the Middle Ages or to early modern times? Is he a representative of medieval heretical dissent or a precursor of Martin Luther, John Calvin, and the sixteenth-century Reformation? Was he merely a local leader of a Czech movement or a figure of wider European significance?

Recent scholars have protested the earlier tendency to depict Hus as a mere echo of English reformer John Wyclif (whose writings he knew and quoted) or a simple forerunner of Luther. These cautions are well taken.

Furthermore, unlike many other reformers, Hus retained much of Catholic theology. He did not teach the doctrine of justification by faith alone, a fact Luther noted when he observed that, unlike himself, Hus had attacked only the life, not the doctrine, of late medieval Catholicism.

All the same, Luther was not entirely without reason when he applied to himself the prophecy attributed to Hus as he faced the martyrs’ pyre: “Today you will roast a lean goose, but a hundred years from now you will hear a swan sing, whom you will leave unroasted and no trap or net will catch him for you.” Luther posted his theses 102 years later; soon after, he read Hus’s work and realized, “We are all Hussites without knowing it.”

Local roots

Hus’s work was deeply rooted in the Czech reform movement that was already well under way when Hus was born in 1372. The religious awakening in Bohemia was related to the emergence of the Czech language and the revival of national identity led by Charles IV, king and emperor, who ruled in Bohemia from 1333 to 1378.

Charles wanted his capital, Prague, to be a great political and cultural center, and in 1348 he established there a university modeled on those at Paris and Oxford. The exchange of ideas that flourished at Charles University profoundly affected Hus and others of his era.

Early proponents of church reform included Konrad Waldhauser and Matej of Janov. These preachers criticized the loose morals of many of their fellow clergy and encouraged the study of the Bible in the Czech language. Scholars have discovered more than 50 manuscripts of the Bible in Czech, all in circulation before the invention of the printing press.

Another key figure in the early Czech reform movement was Jan Milíc from Kromeírž (1325-1375). Like Hus, Milíc was both a scholar and a preacher: he broke through the language barrier by preaching in Latin for the university audience, in German for Prague’s upper classes, and in Czech for the workers and common people. He called for personal conversion, but he also emphasized the practical and ethical consequences of following Christ.

In Prague, Milíc established a house he called “New Jerusalem.” It was a haven for prostitutes, one of the most despised and marginal groups in medieval society. The name was taken from the Book of Revelation and indicates the strong eschatological character of the Czech reform movement.

One of the ironies of church history is that frequently those who have the most acute sense of the future reign of God—of living in the “last days”—are precisely those who invest themselves with purpose and energy in changing things here and now. Hus too brought together the sense of living at the edge of history (for example, the Antichrist was one of his major themes) with an earnest hope for the renewal of church and society.

Milíc is called “the Father of the Czech Reformation,” but he was not able to carry forward the reforms he had begun. He died in Avignon while defending his cause before his accusers at the papal court. But in 1391 some of his disciples established Bethlehem Chapel, a public center in Prague for preaching and worship where Hus was appointed chaplain in 1402.

From the pulpit in Bethlehem Chapel, Hus preached with great power and persuasion to a large number of followers. At the same time, he emerged as a leader in the university, serving terms as both dean and rector. Like Luther a century later, Hus was trained in scholastic theology (though he never obtained the doctorate), but he also appealed to the masses and became widely known as a popular religious leader.

The invisible church

During the two years of exile between his departure from Prague and his trial at Constance, Hus wrote some 15 books. In these he continued to sound the alarm against church abuses, criticizing the papacy and the practice of indulgences. But his most important work during this period was a Latin treatise De Ecclesia (1413), “On the Church.”

Hus insisted that the true church was invisible, the Body of Christ comprised of all the redeemed of all the ages, God’s chosen elect known infallibly only to Him.

“The unity of the church,” Hus wrote, “consists in the bond of predestination, since the individual members are united by predestination, and in the goal of blessedness, since all her sons are ultimately united in blessedness.” The “chief abbot” of the church was not the pope but Christ, and it was possible to be in the church (visible) without being of the church (invisible).

This idea was not new. Wyclif had said much the same thing, echoing earlier theologians such as Augustine. But in the context of the religious awakening in Bohemia, Hus’s correlation of predestination and ecclesiology ignited a national reform movement with revolutionary implications.

Near the end of his life, Wyclif had repudiated the entire papal system and called for its abolition. What Hus called for was not the abolition of the institutional church, nor even the separation of the godly from the impure (as some later Hussites believed), but rather the reform of the church based on the example of Christ and apostolic simplicity.

Just the same, Hus’s appeal to the invisible church, as well as his elevation of Scripture as a superior norm for doctrine, proved a solvent to the kind of extravagant papal claims made by Boniface VIII in his famous bull, Unam Sanctam (1302), which made obedience to the pope a condition for salvation.

The Czech “Magna Carta”

The execution of Hus sent shock waves throughout Bohemia. Nearly 500 Czech nobles gathered in Prague to protest his condemnation and death. They entered into a solemn covenant, pledging to defend the Czech reformation against all external threats.

Out of this gathering emerged the Four Articles of Prague (1419), a manifesto that Czech theologian Jan Milic Lochman has called “the Magna Carta of the Czech Reformation.” Lochman sees these four principles as an extension of Hus’s basic theology.

1. The Word of God is to be preached freely.

Like Wyclif, Hus insisted both that the Scriptures be in the language of the people and that they be the normative rule of faith and conduct for all believers. Hus defied his archbishop’s order to cease preaching because he was committed to a prior authority, namely, the expressed law of Christ set forth in the Bible.

During his trial at Constance, Hus insisted that he be corrected out of the Scriptures before he would retract his views. This did not mean, of course, that he had no respect for the tradition of the church, but rather that church tradition could not be placed above the written Word of God.

In an age when printed books were not available, Hus stressed the importance of viva vox evangelii—”the living voice of the gospel.” For Hus, public preaching of the Word of God was an indispensable means of grace and a sure sign of the true church. The Scriptures must be proclaimed freely, without institutional constraints or political interference.

Some later Hussites, especially the Táborites, went even further than Hus in questioning the necessity of a formal preaching office. Táborites thought that all believers, men and women alike, should bear witness to the spirit-anointed Word. This motif was extended by spiritualists and radical reformers in the sixteenth century, some of whom disparaged the external form of the Bible for the “word of faith” and “inner light” within.

2. The sacrament of the body and blood of Christ is to be served in the form of both bread and wine to all faithful Christians.

The practice of withholding the cup from the laity during the celebration of the Lord’s Supper was rooted in early medieval traditions. By 1414, some of Hus’s disciples had begun to share the cup as well as the bread with their communicants. When the Council of Constance condemned this practice, Hus lent his considerable support to the serving of the Eucharist sub utraque specie (under both kinds).

Eventually, the chalice became the defining symbol of the Czech reformation. By sharing both elements with laity as well as clergy, the Hussites were reintroducing what later became known as the priesthood of all believers.

Unlike Wyclif, Hus supported the doctrine of transubstantiation, which to him meant that serving Communion in both kinds was that much more important. When priests withhold the cup from the laity, they actually become “thieves of the blood of Christ,” as the Hussite leader Jacob of Mies put it.

The eschatological dimension of the Lord’s Supper was also prominent among the Hussites. They often celebrated the Lord’s Supper under the open skies on mountaintops. As Jesus had ascended into heaven from the Mount of Olives, so he returned in bread and wine to celebrate with his people the coming kingdom of God.

3. Priests are to relinquish earthly position and possessions and all are to begin an obedient life based on the apostolic model.

The Hussites emphasized obedience and discipleship. They also picked up the earlier emphasis of St. Francis and the Waldensians in advocating a return to the example of Jesus and the apostolic church. Like Milíc with his ministry to the prostitutes and Hus with his devotion to Jesus, the King of the Poor, later Hussites took seriously the mandate to reform both church and society, with special care extended to “the least of these.”

4. All public sins are to be punished and public sinners in all positions are to be restrained.

In this last article, we hear a plea for intentional Christianity and a protest against the laxity that is endemic to every established religion. Christians should obey and live by the law of Christ and this requires both personal and corporate discipline.

There is an egalitarian thrust in that sinners “in all positions” are to be held equally accountable to the community of faith. This emphasis of the Hussite movement would later be picked up by Calvin and the Reformed tradition with their concern to bring every dimension of human life and culture under the lordship of Jesus Christ.

Many scholars see the Czech reform movement as the First Reformation. Luther claimed continuity with Hus in many respects, although there was a theological chasm between the two on the doctrine of justification. Likewise, Hus was not strictly a Wyclifite, although there were important contacts and some influence between England and Bohemia.

Clearly, Hus stood in an indigenous tradition of Czech reformers who emphasized preaching, studying the Scriptures, and eliminating clerical abuses. Hus’s rediscovery of the Augustinian doctrine of the invisible church enabled him to criticize contemporary church practices in the light of God’s sovereignty over time and eternity.

The motto of Hus’s life was “truth conquers all.” He was not without fault, and we may criticize him for his lack of understanding and theological mistakes. But all Christians can surely respond with gratitude to the kind of faith set forth in this letter written by Hus less than two weeks before his death:

“Oh most kind Christ, draw us weaklings after Thyself, for unless Thou draw us, we cannot follow Thee! Give us a courageous spirit that it may be ready; and if the flesh is weak, may Thy grace go before, now as well as subsequently. For without Thee, we can do nothing, and particularly not go to a cruel death for Thy sake. Give us a valiant spirit, a fearless heart, the right faith, a firm hope, and perfect love, that we may offer our lives for Thy sake with the greatest patience and joy. Amen.”

Timothy George is dean of Beeson Divinity School of Samford University and executive editor of Christianity Today

Copyright © 2000 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.