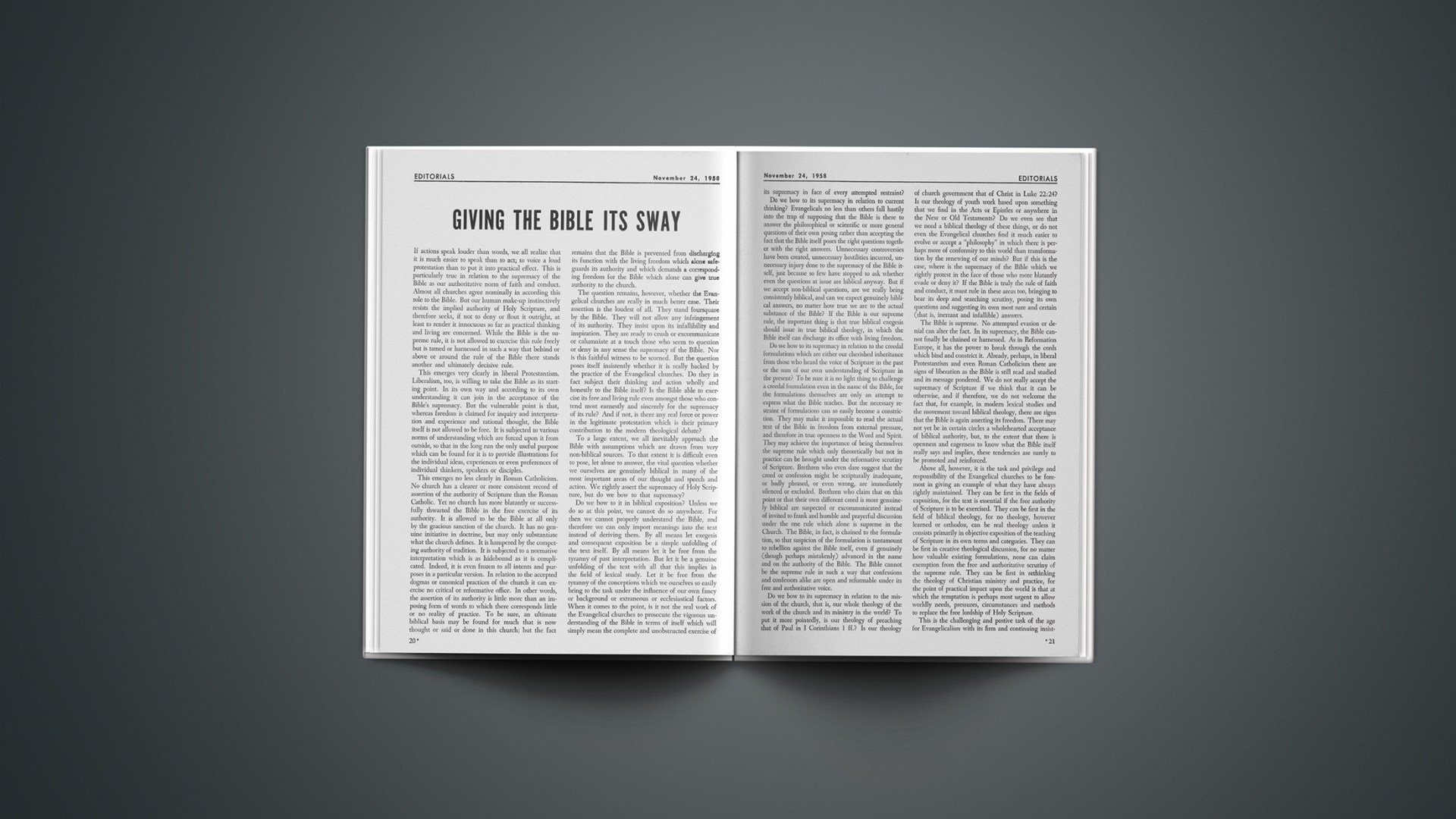

Giving The Bible Its Sway

If actions speak louder than words, we all realize that it is much easier to speak than to act; to voice a loud protestation than to put it into practical effect. This is particularly true in relation to the supremacy of the Bible as our authoritative norm of faith and conduct. Almost all churches agree nominally in according this role to the Bible. But our human make-up instinctively resists the implied authority of Holy Scripture, and therefore seeks, if not to deny or flout it outright, at least to render it innocuous so far as practical thinking and living are concerned. While the Bible is the supreme rule, it is not allowed to exercise this rule freely but is tamed or harnessed in such a way that behind or above or around the rule of the Bible there stands another and ultimately decisive rule.

This emerges very clearly in liberal Protestantism. Liberalism, too, is willing to take the Bible as its starting point. In its own way and according to its own understanding it can join in the acceptance of the Bible’s supremacy. But the vulnerable point is that, whereas freedom is claimed for inquiry and interpretation and experience and rational thought, the Bible itself is not allowed to be free. It is subjected to various norms of understanding which are forced upon it from outside, so that in the long run the only useful purpose which can be found for it is to provide illustrations for the individual ideas, experiences or even preferences of individual thinkers, speakers or disciples.

This emerges no less clearly in Roman Catholicism. No church has a clearer or more consistent record of assertion of the authority of Scripture than the Roman Catholic. Yet no church has more blatantly or successfully thwarted the Bible in the free exercise of its authority. It is allowed to be the Bible at all only by the gracious sanction of the church. It has no genuine initiative in doctrine, but may only substantiate what the church defines. It is hampered by the competing authority of tradition. It is subjected to a normative interpretation which is as hidebound as it is complicated. Indeed, it is even frozen to all intents and purposes in a particular version. In relation to the accepted dogmas or canonical practices of the church it can exercise no critical or reformative office. In other words, the assertion of its authority is little more than an imposing form of words to which there corresponds little or no reality of practice. To be sure, an ultimate biblical basis may be found for much that is now thought or said or done in this church; but the fact remains that the Bible is prevented from discharging its function with the living freedom which alone safeguards its authority and which demands a corresponding freedom for the Bible which alone can give true authority to the church.

The question remains, however, whether the Evangelical churches are really in much better case. Their assertion is the loudest of all. They stand foursquare by the Bible. They will not allow any infringement of its authority. They insist upon its infallibility and inspiration. They are ready to crush or excommunicate or calumniate at a touch those who seem to question or deny in any sense the supremacy of the Bible. Nor is this faithful witness to be scorned. But the question poses itself insistently whether it is really backed by the practice of the Evangelical churches. Do they in fact subject their thinking and action wholly and honestly to the Bible itself? Is the Bible able to exercise its free and living rule even amongst those who contend most earnestly and sincerely for the supremacy of its rule? And if not, is there any real force or power in the legitimate protestation which is their primary contribution to the modern theological debate?

To a large extent, we all inevitably approach the Bible with assumptions which are drawn from very non-biblical sources. To that extent it is difficult even to pose, let alone to answer, the vital question whether we ourselves are genuinely biblical in many of the most important areas of our thought and speech and action. We rightly assert the supremacy of Holy Scripture, but do we bow to that supremacy?

Do we bow to it in biblical exposition? Unless we do so at this point, we cannot do so anywhere. For then we cannot properly understand the Bible, and therefore we can only import meanings into the text instead of deriving them. By all means let exegesis and consequent exposition be a simple unfolding of the text itself. By all means let it be free from the tyranny of past interpretation. But let it be a genuine unfolding of the text with all that this implies in the field of lexical study. Let it be free from the tyranny of the conceptions which we ourselves so easily bring to the task under the influence of our own fancy or background or extraneous or ecclesiastical factors. When it comes to the point, is it not the real work of the Evangelical churches to prosecute the vigorous understanding of the Bible in terms of itself which will simply mean the complete and unobstructed exercise of its supremacy in face of every attempted restraint?

Do we bow to its supremacy in relation to current thinking? Evangelicals no less than others fall hastily into the trap of supposing that the Bible is there to answer the philosophical or scientific or more general questions of their own posing rather than accepting the fact that the Bible itself poses the right questions together with the right answers. Unnecessary controversies have been created, unnecessary hostilities incurred, unnecessary injury done to the supremacy of the Bible itself, just because so few have stopped to ask whether even the questions at issue are biblical anyway. But if we accept non-biblical questions, are we really being consistently biblical, and can we expect genuinely biblical answers, no matter how true we are to the actual substance of the Bible? If the Bible is our supreme rule, the important thing is that true biblical exegesis should issue in true biblical theology, in which the Bible itself can discharge its office with living freedom.

Do we bow to its supremacy in relation to the creedal formulations which are either our cherished inheritance from those who heard the voice of Scripture in the past or the sum of our own understanding of Scripture in the present? To be sure it is no light thing to challenge a creedal formulation even in the name of the Bible, for the formulations themselves are only an attempt to express what the Bible teaches. But the necessary restraint of formulations can so easily become a constriction. They may make it impossible to read the actual text of the Bible in freedom from external pressure, and therefore in true openness to the Word and Spirit. They may achieve the importance of being themselves the supreme rule which only theoretically but not in practice can be brought under the reformative scrutiny of Scripture. Brethren who even dare suggest that the creed or confession might be scripturally inadequate, or badly phrased, or even wrong, are immediately silenced or excluded. Brethren who claim that on this point or that their own different creed is more genuinely biblical are suspected or excommunicated instead of invited to frank and humble and prayerful discussion under the one rule which alone is supreme in the Church. The Bible, in fact, is chained to the formulation, so that suspicion of the formulation is tantamount to rebellion against the Bible itself, even if genuinely (though perhaps mistakenly) advanced in the name and on the authority of the Bible. The Bible cannot be the supreme rule in such a way that confessions and confessors alike are open and reformable under its free and authoritative voice.

Do we bow to its supremacy in relation to the mission of the church, that is, our whole theology of the work of the church and its ministry in the world? To put it more pointedly, is our theology of preaching that of Paul in 1 Corinthians 1 ff.? Is our theology of church government that of Christ in Luke 22:24? Is our theology of youth work based upon something that we find in the Acts or Epistles or anywhere in the New or Old Testaments? Do we even see that we need a biblical theology of these things, or do not even the Evangelical churches find it much easier to evolve or accept a “philosophy” in which there is perhaps more of conformity to this world than transformation by the renewing of our minds? But if this is the case, where is the supremacy of the Bible which we rightly protest in the face of those who more blatantly evade or deny it? If the Bible is truly the rule of faith and conduct, it must rule in these areas too, bringing to bear its deep and searching scrutiny, posing its own questions and suggesting its own most sure and certain (that is, inerrant and infallible) answers.

The Bible is supreme. No attempted evasion or denial can alter the fact. In its supremacy, the Bible cannot finally be chained or harnessed. As in Reformation Europe, it has the power to break through the cords which bind and constrict it. Already, perhaps, in liberal Protestantism and even Roman Catholicism there are signs of liberation as the Bible is still read and studied and its message pondered. We do not really accept the supremacy of Scripture if we think that it can be otherwise, and if therefore, we do not welcome the fact that, for example, in modern lexical studies and the movement toward biblical theology, there are signs that the Bible is again asserting its freedom. There may not yet be in certain circles a wholehearted acceptance of biblical authority, but, to the extent that there is openness and eagerness to know what the Bible itself really says and implies, these tendencies are surely to be promoted and reinforced.

Above all, however, it is the task and privilege and responsibility of the Evangelical churches to be foremost in giving an example of what they have always rightly maintained. They can be first in the fields of exposition, for the text is essential if the free authority of Scripture is to be exercised. They can be first in the field of biblical theology, for no theology, however learned or orthodox, can be real theology unless it consists primarily in objective exposition of the teaching of Scripture in its own terms and categories. They can be first in creative theological discussion, for no matter how valuable existing formulations, none can claim exemption from the free and authoritative scrutiny of the supreme rule. They can be first in rethinking the theology of Christian ministry and practice, for the point of practical impact upon the world is that at which the temptation is perhaps most urgent to allow worldly needs, pressures, circumstances and methods to replace the free lordship of Holy Scripture.

This is the challenging and postive task of the age for Evangelicalism with its firm and continuing insistence upon the normativeness of the Bible as our rule of faith and conduct. It is not enough to assert this against the world and others. What is now required is to show it in practice for the world and others. It is not important that we should increase the vociferousness or violence of our assertion. What is required is that Evangelicals first should show what it means in the positive subjection of their own exposition, thinking, confession and practice to the free authority of the Bible. Then others will see that they really mean what they assert. They will also see what the assertion means. Indeed, it may well be that, unable to evade or escape the enduring supremacy of the Bible, they will be caught up in the movement of reformation and reconstruction in which the Bible is again the free and living voice which rules supreme in the faith and practice of the Church.

END

Election Trends: Observations And Lessons

Whatever truth there may be in President Eisenhower’s post-election appraisal (and it was a generalization) that the American public “obviously voted for … the spenders,” no sound judgment will view the national election results as a mandate for bigger government, wider controls, larger expenditures, more inflation.

As many interpretations are likely to be put upon the election outcome as there are special interests.

Labor bosses will tend to view the fate of right-to-work laws as a blanket approval of unionism, as a mandate to Congress to enact labor’s legislative program, including “full employment.” Politicians indebted to the labor vote (the Committee on Political Education [COPE], political arm of AFL-CIO, promptly interpreted election results as a .685 efficiency in its endorsements) will be tempted to ease demand for union reforms and curtailment of graft. As long as bosses achieve their special ends through established parties, the prospect of a Labor Party in American politics remains submerged. Labor’s legislative goals include widening the right-to-work setback and multiplying required welfare benefits that corrode the free enterprise system. What will be swiftly forgotten is that 2 million Galifornians approved Senator Knowland’s gubernatorial race on a right-to-work platform; that a special right-to-work proposition on the ballot was supported by 1½ million voters there. In fact, although right-to-work legislation carried in only one of the six states in which an amendment was sought, more than 3 million voters upheld it in these states in the face of highly powered union opposition, and the Kansas victory widened the number of right-to-work states to 19.

Nor is it possible to view the election as a strategic breakthrough for some religious faction in American life, Roman Catholicism especially. Senator John Kennedy’s re-election in Massachusetts was expected and, despite his popularity, it remains unlikely that he will be his party’s presidential nominee. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown’s election in California was in no sense a test of Roman Catholic strength; it resulted from the split in Republican ranks and organized labor’s campaign against Senator Knowland. Despite a vast Catholic minority in California, voters opposed taxing private schools below college level (from which parochial schools stand to gain most) by a two-to-one margin, with the encouragement of leading Protestant religious journals.

An eight-term campaigner, Congressman Brooks Hays, Democratic representative from Arkansas and president of the Southern Baptist Convention, narrowly lost re-election when a political neophyte, Dr. Dale Alford, outspoken segregationist, unofficially approved by Governor Faubus, conducted an eight-day write-in campaign. It was Hays who arranged the Eisenhower-Faubus meeting at Newport, Rhode Island, in 1957. His position as a “moderate segregationist” was made increasingly difficult in Arkansas through secular and ecclesiastical integrationist pronouncements neglectful of States’ rights. This will probably not be the last time in American life, unless there is some major regrouping of political forces, that an evangelical moderate is likely to suffer wounds in the crossfire of extremists to the right and to the left.

President Eisenhower rightly senses that the great issue before the American people today is the survival of the tradition of liberty. The “whole theory of liberty and freedom and of free enterprise” may be imperiled, he warns, unless present “money spending” trends are halted. As dangerous spurs to inflation he singles out the continuing wage-price spiral and unnecessary Federal spending involving huge budget deficits. But Mr. Eisenhower’s own party has neglected its opportunities to revise this tendency in recent years which have witnessed a further dilution of the dollar and approval of the largest peace-time budget in history. Under pressure from its liberal wing, the Republican party drifted from its own principles, and even tended to disguise its Republicanism so that the image of the party in the public mind was confused and uncertain. Coupled with the far-reaching strength of Democratic forces, this added up to nothing less than a Republican debacle. Even Republican successes (Nelson Rockefeller as governor in New York; Senator Barry Goldwater in Arizona) reflected a difference almost as wide as the “house divided” in which terms President Eisenhower has depicted his Democratic opponents.

The November vote seems not so much a permanent Democratic commitment as an alternative to anxiety. Where it leads next is important for the nation, and that direction is not at all sure.

END