Many observers are speaking, often with reluctance, of the “resurgence of evangelical Christianity.” The modern mind had hardly expected the twentieth century to lift conservative Christianity once again into such significant orbit. Not only philosophers and sociologists, but even theologians awaited the secure triumph of classical liberalism and the decline of biblical theology. Now, however, it is clear that the religious experiment dating from Schleiermacher to Fosdick detoured Protestantism into the wilderness of modernity, and that the Great Tradition—the heritage of Moses and the prophets, and of Jesus and his apostles—was not really to be found there.

In this century after Marx and Darwin, when theological destinies revolve around such modern names as Dewey and Tillich and Niebuhr, it would be absurd to contend that evangelical Christianity is the only option on the horizon of contemporary decision. Many false gods peopled the ancient world; the modern world too has more than its quota. Swift and sundry have been the regroupings of theological positions in our shaky generation—liberalism, humanism, realism, neo-orthodoxy—and their adjustments and readjustments are not over.

Over against them I speak nonetheless of evangelical advance, of a recovery in the religious realm of new relevance and vitality by the forces of biblical theology and evangelism. The day is gone when religious couriers bear tidings only of loss after loss for the evangelical movement; of conservative scholars dwindling until at last Machen and Warfield seem almost to stand alone; of revealed religion demeaned as fundamentalist cultism and fundamentalism disparaged in turn as sheer anti-intellectualism. That day is gone. One fact stands sure: evangelical claims are being reasserted today with a vigor and wideness surprising to most interpreters of contemporary religious life.

To describe this phenomenon, the term “resurgence” is perhaps well chosen. It means much the same, of course, as revival or renaissance. But it is less familiar, less speech worn, and therefore avoids the full connotation of those words. We are witnessing no spiritual breakthrough of Reformation proportions, at least not yet. Spontaneous unleashings of spiritual dynamisms there are, however, and with these a dramatic vitality manifest at grass roots, and a clarion call to total dedication ringing with the fervor of martyrs and calling even communism to repentance.

In this surging spiritual crescendo discords are also to be heard, and it is only fair to make note of them. These flaws may not be failures of the kind depressing other spiritual movements of the day, but they are distressing weaknesses nonetheless.

Signs Of Weakness

For one thing, the cause of Christian unity today is publicly identified with theologically inclusive ecumenism more than with doctrinally exclusive evangelicalism. The ecumenical movement may have many deficiencies—it may elevate the concern for unity above passion for the truth, and it may represent Protestantism less universally and less objectively than its spokesmen imply—but nonetheless it appears to be a denominational consolidation linking widely scattered churches into one vast world community. Criticize this effort as they will, stress the fact that the unity of believers is essentially spiritual as they do, the fragmented evangelical churches in their judgment of ecumenically organized Protestantism nevertheless fail at two levels. They lag in stating a compelling theology of the visible unity of the evangelical churches, and they fail to exhibit to the modern world that outward cohesion which submerges the spirit of competition to one common witness. Free enterprise is a good thing even in religion, but Christian rivalry is out of bounds. Evangelical Protestantism lives too fully on the fissuring front of denominational divisions, and teems even along its far-flung evangelistic lines with the clan spirit of party labels. The New Testament family of faith radiates a central concern for the unity of believers in the world. In our generation the evangelical movement has lost too much of the passion for Christian unity.

Then too, the lack of cultural vision and social concern has plagued twentieth century evangelicals. Of course, social action may stray far from the light of the Cross and thus become short-lived and self-defeating. The social gospel a generation ago forfeited, even betrayed, the most propitious opportunity for world impact that Protestantism may ever again see. And the negative social outlook in evangelical circles must be understood in part as a protest against this evangelsuppressing social activism, even as a reaction against a social vision lacking in redemptive depth. The neglected message of the foregiveness of sins and supernatural regeneration, faithfully proclaimed by evangelicals, now became virtually the whole of the Gospel, and its social significance was largely confined to divine deliverance from personal vices. Unchallenged by the Lordship of Christ were many great areas of culture, literature, and the arts. Where Christian education survived as a commendable ideal, the river of pietism often ran deeper than the currents of world-and-life concern, applying the Christian revelation comprehensively to the social crisis, with the result that the evangelical challenge to the secular universities scored low. The heartbeat of evangelical worship and witness was set to tawdry music in which the world could hear the beat of the times more than the cadences of eternity. But after the romantic dream of the social gospel faded, it was almost inevitable that a new sense of urgency about the social order and the culture crisis should devolve upon the evangelical commitment.

While conditioning the hope of a new life for man and society upon individual response to the evangel and the birth of a new race of men, evangelical Christians in principle related Christ’s supernatural incarnation, atonement, and resurrection to the redemption of humanity and history. The force of evangelical social impact, however, still lags in its first phases in the world of labor, the world of learning and the arts, and in other centers of modern culture. Whatever may be said of the current resurgence of evangelicalism, it has not yet borne the undeniable social fruits of the Evangelical Revival of the age of Wesley and Whitfield, whose fervent piety quickened all England from 1750 to 1830, nor of the 1859 Revival which carried new life to English-speaking Christianity both in the United States and Great Britain and ushered in a half century of church influence and expansion.

Signs Of Vitality

In view of these weaknesses, some may ask, why speak of evangelical resurgence? Lack of direct political and cultural influence, lack of organizational cohesion in the evangelical movement, lack of worldly greatness—are not these disqualifying factors? I think not. The evangelical movement does not rely on ecclesiastical structuring, nor does it promote the direct Christianization of the sociopolitical order as its first task. Modern Christians are prone to appeal to the early Church while reconstructing and romanticizing it by modern norms. Even the infant churches were tense with turmoil when the first apostles carried the Gospel to the pagan West, although their disunity was not so often due to ecclesiastical politics and politicians as in our day. From the outset, even in ancient Greece with its heritage of classical culture, the Christian movement had to confess the virtual absence from its ranks of the wise, the noble, the mighty. And a characteristic of ancient intellectuals, no less than of modern minds, has been the tendency to discount the Christian impact as a cultural force. Seldom is a pagan society aware of vital spiritual energies in its midst. “The greatest religious change in the history of mankind,” wrote Lecky in his History of European Morals, took place “under the eyes of a brilliant galaxy of philosophers and historians” who disregarded “as simply contemptible an agency which all men must now admit to have been … the most powerful moral lever that has ever been applied to the affairs of men” (Vol. I, p. 338). The surest index to the spiritual dynamisms quickening the popular masses is never simply a count of professional noses. Whatever its weaknesses, the evangelical movement flames today with new fire, and we must measure its power in modern life.

Apostolic Evangelism

1. The spirit of apostolic evangelism hovers over this movement. A hallmark of its witness is the appeal for “personal decision for Christ”—in evangelistic services, in house to house visitation, in mass meetings, on radio and television and screen. It was Charles E. Fuller who first made the radio a national and even international instrument for confronting men with their sins and the offer of God’s forgiveness; others followed in his train. It was an evangelistic passion to reach lost men that made the screen—the silent film and then the sound film—not simply a medium of entertainment or of religious education, but a vehicle of spiritual decision and commitment. It was Billy Graham who so made television the mirror of personal destinies that mail inquiries to New York had to be transported literally by the carload. Criticize Mr. Graham as men may for halting short of a complete agenda for civilization, his message rings with the only priorities discoverable in the Acts of the Apostles: the death of Jesus Christ for sinners, his resurrection and exaltation as Lord and Saviour, and the indispensability of man’s total commitment to the living God. In an age wherein social gospelism had come to disparage if not to disdain evangelism, Graham’s plea for decision drew phenomenal response in New York, San Francisco, London, Glasgow, Berlin, Madras, and Melbourne that perplexed earnest churchmen who sought to improve Christianity’s position mainly by unifying its organizational structures. The spirit of apostolic evangelism still hovers over the evangelical movement.

Missionary Martyrdom

2. The spirit of missionary martyrdom is another evangelical hallmark. In the past generation it was John and Betty Stam facing Communists in South China and preferring death to denial of Jesus Christ; in our times, the missionary martyrs of Ecuador, willing to give their lives to reach the Auca Indians for Christ. Such martyrdoms are a needless waste to all who measure spiritual worth by the yardstick of religious synthesis and syncretism. Place a premium on religions-in-general and Christianity becomes a necessary offense through its once-for-all and one-and-only claim of redemption in Christ. The martyr spirit wanes whenever men “rethinking missions” lay stress on “the truth in all” faiths. But it stirs and throbs wherever missionaries are convinced “there is no other name under heaven given among men whereby we must be saved.” To those five widows of Ecuador their husbands’ contact with the Aucas (even by maryrdom) was half the answer to a prayer to reach these benighted pagans for Christ. Since then, the women missioners have moved in with the Aucas, instructing them in the promises of redemption. Is it any wonder that New York publishers, seeking a modern missionary epic, reached for Elisabeth Elliot’s Through Gates of Splendor, and that more than 100,000 readers have purchased copies? The spirit of missionary martyrdom throbs blood-fresh in the evangelical witness.

The Inspired Scriptures

3. The strength of evangelical Christianity lies also in its reliance on the inspired Scriptures as a sword and shield. Other theological movements always invoke the Scriptures somewhat apologetically. Before they say “Thus saith the Lord” they draw up a twentieth century preamble for saying it with modern overtones: “The Bible is this, but not that,” and the not that dissolves much of the this. Where but among evangelical Protestants is Scripture named as the Word of God with the trusting confidence of the prophets and apostles, and of Jesus of Nazareth in the midst of them?

About a dozen years ago in New England I was lunching with a distinguished personalist scholar, Dr. Albert C. Knudson, late dean of the School of Theology at Boston University. These occasional luncheons with men of liberal views were always times of theological exchange that I treasured. Mrs. Knudson had but recently died, and I recall that as we drove to Dr. Knudson’s home he mentioned that his recent thoughts had been much about the subject of immortality—of how there must be immortality if the most treasured values of this life are to be preserved. “There must be immortality,” he said, “if this life is to make sense.” With a feeling for the moment, I added: “Of course there is immortality.… Remember (our Lord’s words in John 14) ‘if it were not so, I would have told you.’ ” I shall not forget Dean Knudson’s reply. “You know,” he said, with a long pause, “I have never thought of those words in that way before.” That way is the evangelical way. “Did not our hearts burn within us,” the disciples commented, “while he (the risen Lord) opened to us the Scriptures” (Luke 24:32).

To the disciples of Jesus Christ, Scripture was life’s lamp and light; “ye do err,” he reminded his contemporaries, “not knowing the Scriptures.” But for most modern theologians, the Bible gains its reliability from its concurrence with criticism: “ye do err, not knowing the critics.” I would not deny biblical criticism has a legitimate task. But dare we ignore the vast diversity among the critics themselves and the extensive disagreement of their dogmatisms? Many first-rate scholars—international and interdenominational—see no need to deprive Scripture of its power and authority in modern life, as witness the symposium on Revelation and the Bible just issued by two dozen world scholars.

Last year I was invited to speak at Union Theological Seminary, New York, on the authority of Scripture, and was given as courteous a hearing as one could wish. Yet the very first question raised by a student panel was this: ‘Would you say that higher criticism has made a positive contribution to faith, or that its influence has been wholly negative?” Though the theme be the ancient Scriptures, the center of divinity school interest is modern criticism. And my answer, now as then, is that modern criticism has shown itself far more efficient in creating faith in the existence of manuscripts for which there is no overt evidence (J, E, P, D, Q, first century non-supermaturalistic gospels, and second century redactions, and so on) than in sustaining the confidence of young intellectuals within the churches in the only writings that the Christian movement historically has received as a sacred trust. Modern criticism too often bestows prestige upon the critics by defaming the sacred writers.

“The Bible says” is not mere Graham platitude nor a fundamentalist cliché; it is the note of authority in Protestant preaching, lost by the meandering modernism of the past generation, held fast by the evangelical movement. Evangelical Christianity retains its reliance on the Bible as sword and shield.

4. Another mark of evangelical vitality, I think, is the theological approach to education and the social order. There remain long distances for evangelicals to travel in these spheres, and today’s culture crisis runs so deep that no Christian agency has time for self-congratulation. But we may speak of evangelical gains as well as of pitfalls.

In education, evangelicals in the main sounded the Protestant criticism of John Dewey’s experimental philosophy, which lost supernatural realities and fixed truth and morality in the smog of evolutionary naturalism. It was the evangelicals who defended the unique contribution of Christian education when other Protestant forces crowned the cause of religion-in-general and blunted the priorities of revealed religion, and even diverted evangelical institutions and endowments to nonevangelical causes. Meanwhile, evangelicals championed the distinctively Christian school—the Christian seminary, the Christian college, the Christian day school—though limited resources often lowered their standards, and their exclusive witness sometimes raised barriers to recognition of which they were worthy.

It is well to remind ourselves that at the root of this evangelical interest in education lies a recognition of the role of the intellect in the service of God. During the past generation fundamentalism often was caricatured as anti-intellectual—and it would be difficult to defend the movement in toto against some of the complaints. But critics of fundamentalism today take a different line, acknowledging unwittingly the one-sidedness of earlier appraisals. Now they criticize fundamentalism for rationalism rather than irrationalism. In the present climate of theology, I think, evangelicals have less to fear from this type of criticism than their critics from the modern revolt against reason. They respect the Christian warning against the pride of reason—against making man’s mind an absolute and denying its dignity in the image of God, against refusal to bring man’s fallen reason into devout conformity to the mind of God. Yet they are confident that faith and reason are made for each other. They seek the rational integration of all life’s experiences under God. Here the great battle of contemporary theology is being fought. The newer forms of theology are skeptical about reason, even reason under God—where it belongs. They tend to rob revelation of rational status; they contrast theological truth with scientific and historical truth in a manner costly to Christian beliefs; they surrender Christianity’s significance as a world-and-life view because they no longer expect the rational unity of life and culture. Evangelical Christianity’s vision for education and culture honors divine revelation in the service of man, and it honors human reason in the service of God. It would be the greatest of irony were modern Christianity to give to Communists (who really do not understand the nature and glory of reason) the opportunity of systematically interpreting the whole of life and culture on alien naturalistic principles, while the disciples of Jesus Christ are stripped of the right to bring the whole of life and its experiences into the reasonable service of God.

The theological approach to the social order bears also in a decisive way upon the whole question of human freedom and duty. Political earthquakes the world over are shaking the foundations of freedom and destroying the sense of responsibility. The delinquent democracies, no longer aware of a mission “under God,” and seeking only the majority vote of the masses, are steadily declining toward chaos and anarchy, while totalitarian and collective powers are dissolving human liberties and destroying the opportunity for voluntarism. But evangelical Christianity relies on God’s revelation for the timeless moral principles of personal and social ethics and holds promise and potency for slowing, and even stopping and reversing, the modern travesty on human dignity. And evangelical concern is rising today for all life’s freedoms—spiritual, economic, political—with new awareness that man’s liberties depend in a determinative way upon the fate of revealed religion in our generation. The evangelical challenge to the social order reinforces man’s sense of obligation to God and neighbor, his sense of divinely given liberties and duties, and pledges new meaning and worth to the social order in our chaotic times.

There are other signs of awakening of which only briefest mention is possible. One could speak of World Vision conferences spurring thousands of native pastors throughout the Orient to deeper Christian commitment in the face of advancing Communist totalitarianism; of the witness of Inter-Varsity Fellowship on university campuses, and its remarkable influence especially upon the younger clergy of the Church of England, and the recruiting of many college converts by Campus Crusade for Christ; of the steady progress of evangelical institutions with accrediting agencies; of the emergence of an evangelical literature of Bible commentaries, reference works, and texts in the spheres of doctrine and ethics; of the emergence—if propriety will permit the mention—of an international, interdenominational journal of evangelical conviction in the fortnightly form of CHRISTIANITY TODAY; of the rising evangelical concern for all life’s freedoms—spiritual, economic, political—and the new awareness that man’s liberties depend in a crucial way upon the fate of revealed religion in our generation. Upon the rising tide of evangelical commitment in our times may well depend the Christian dedication of multitudes for whose allegiance the forces of atheism are today making history’s supreme bid. Either we shall soon see evangelical revival flaming like a prairie fire at grass roots, or a mighty wave of persecution will deluge the Christian movement, and in the once-Christian West the faithful remnant will go underground.

END

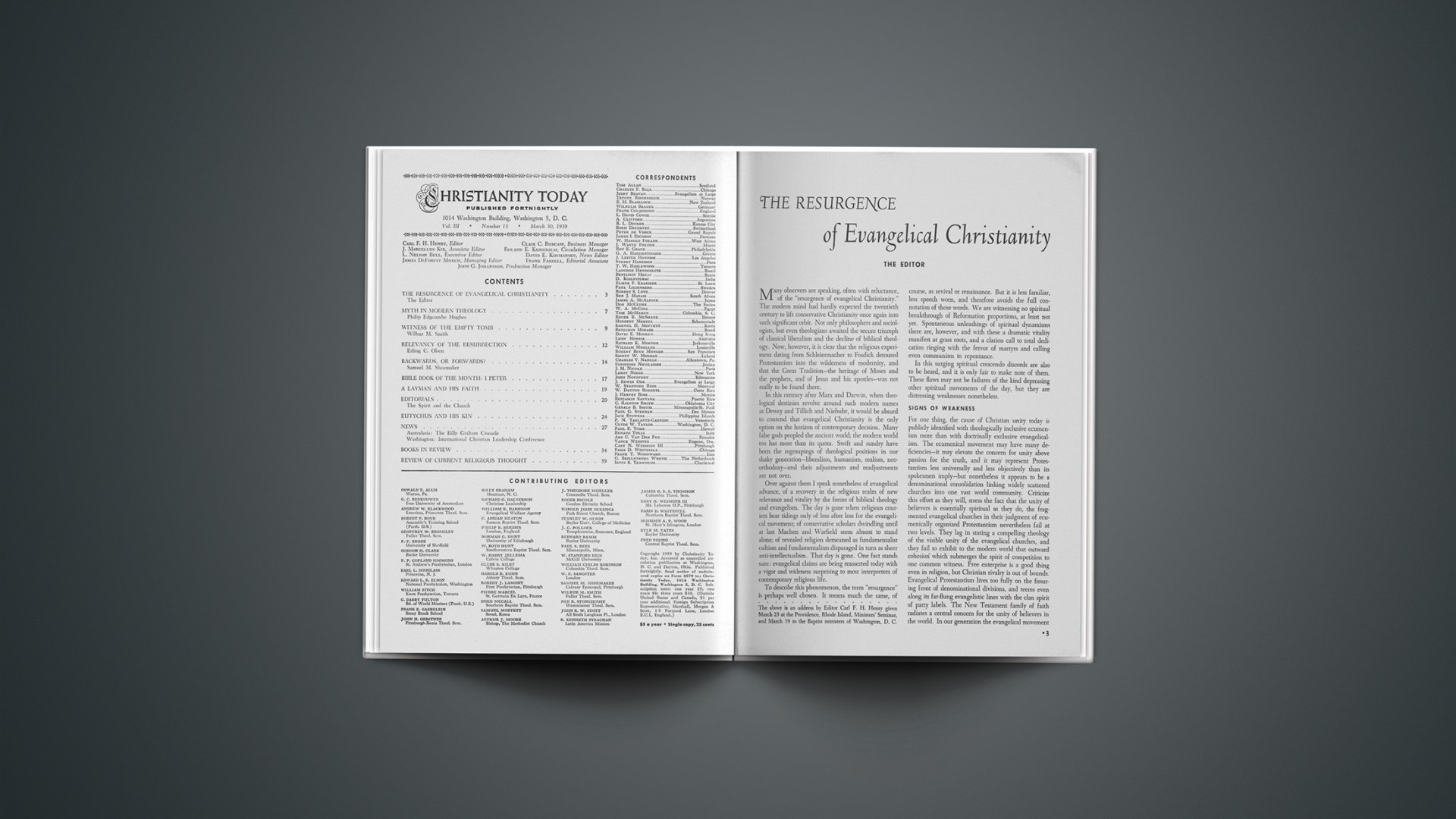

The above is an address by Editor Carl F. H. Henry given March 23 at the Providence, Rhode Island, Ministers’ Seminar, and March 19 to the Baptist ministers of Washington, D. C.