“Had not Christ by his own omnipotence healed some lepers, none would have been healed; had he not opened some sightless eyes, all the blind would have continued in darkness.” So wrote Charles Hodge, noted Presbyterian theologian, to stress the fact that, in the present state of mankind, had not God chosen to rescue some from the error of their way, none would be saved. And all Protestants agree. But theologians today debate the nature of divine election no less vigorously than in earlier Christian ages. Does divine election imply God’s sovereign or his conditional choice of individuals?

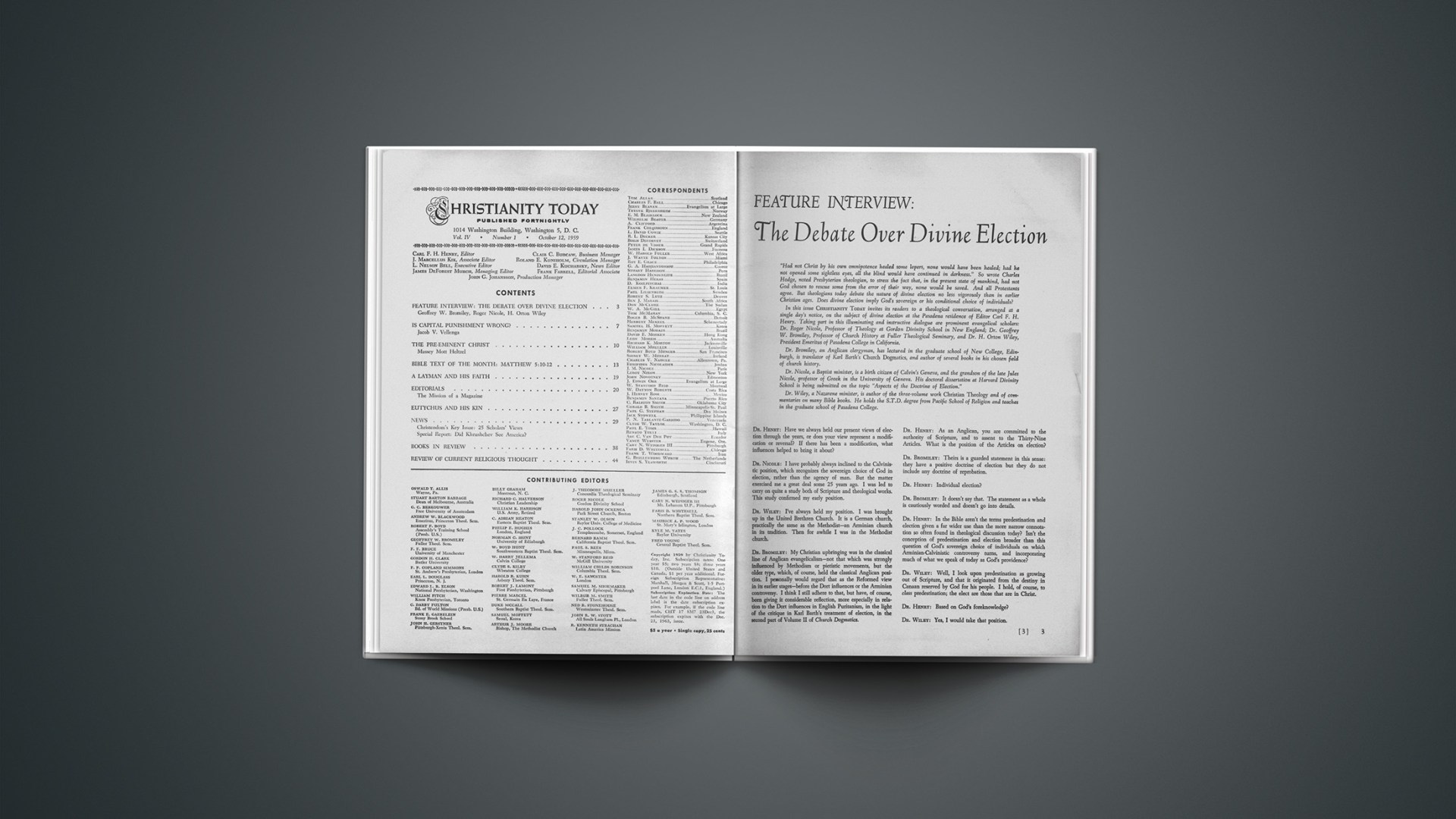

In this issueCHRISTIANITY TODAYinvites its readers to a theological conversation, arranged at a single day’s notice, on the subject of divine election at the Pasadena residence of Editor Carl F. H. Henry. Taking part in this illuminating and instructive dialogue are prominent evangelical scholars: Dr. Roger Nicole, Professor of Theology at Gordon Divinity School in New England; Dr. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Professor of Church History at Fuller Theological Seminary, and Dr. H. Orton Wiley, President Emeritus of Pasadena College in California.

Dr. Bromiley, an Anglican clergyman, has lectured in the graduate school of New College, Edinburgh, is translator of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics, and author of several books in his chosen field of church history.

Dr. Nicole, a Baptist minister, is a birth citizen of Calvin’s Geneva, and the grandson of the late Jules Nicole, professor of Greek in the University of Geneva. His doctoral dissertation at Harvard Divinity School is being submitted on the topic “Aspects of the Doctrine of Election.”

Dr. Wiley, a Nazarene minister, is author of the three-volume work Christian Theology and of commentaries on many Bible books. He holds the S.T.D. degree from Pacific School of Religion and teaches in the graduate school of Pasadena College.

DR. HENRY: Have we always held our present views of election through the years, or does your view represent a modification or reversal? If there has been a modification, what influences helped to bring it about?

DR. NICOLE: I have probably always inclined to the Calvinistic position, which recognizes the sovereign choice of God in election, rather than the agency of man. But the matter exercised me a great deal some 25 years ago. I was led to carry on quite a study both of Scripture and theological works. This study confirmed my early position.

DR. WILEY: I’ve always held my position. I was brought up in the United Brethren Church. It is a German church, practically the same as the Methodist—an Arminian church in its tradition. Then for awhile I was in the Methodist church.

DR. BROMILEY: My Christian upbringing was in the classical line of Anglican evangelicalism—not that which was strongly influenced by Methodism or pietistic movements, but the older type, which, of course, held the classical Anglican position. I personally would regard that as the Reformed view in its earlier stages—before the Dort influences or the Arminian controversy. I think I still adhere to that, but have, of course, been giving it considerable reflection, more especially in relation to the Dort influences in English Puritanism, in the light of the critique in Karl Barth’s treatment of election, in the second part of Volume II of Church Dogmatics.

DR. HENRY: As an Anglican, you are committed to the authority of Scripture, and to assent to the Thirty-Nine Articles. What is the position of the Articles on election?

DR. BROMILEY: Theirs is a guarded statement in this sense: they have a positive doctrine of election but they do not include any doctrine of reprobation.

DR. HENRY: Individual election?

DR. BROMILEY: It doesn’t say that. The statement as a whole is cautiously worded and doesn’t go into details.

DR. HENRY: In the Bible aren’t the terms predestination and election given a far wider use than the more narrow connotation so often found in theological discussion today? Isn’t the conception of predestination and election broader than this question of God’s sovereign choice of individuals on which Arminian-Calvinistic controversy turns, and incorporating much of what we speak of today as God’s providence?

DR. WILEY: Well, I look upon predestination as growing out of Scripture, and that it originated from the destiny in Canaan reserved by God for his people. I hold, of course, to class predestination; the elect are those that are in Christ.

DR. HENRY: Based on God’s foreknowledge?

DR. WILEY: Yes, I would take that position.

DR. NICOLE: The biblical language is somewhat varied. The term predestinate itself is not found often in Scripture—about four times, if I’m not mistaken—and there are other terms: counsel, and determination, and then, foreknowledge; while the term providence, commonly used in theology, if I remember rightly, is not found in Scripture at all. So the whole matter of God’s relationship to his creation, which is subsumed under providence, may also be subsumed under the general doctrine of the decrees. And the decrees are, in part at least, made manifest in connection with salvation in the doctrine of predestination. So that I would say predestination is part of the decrees, and the decrees, if you want, are a broader term that includes also providence—although the term providence is commonly used with respect to the precise relation that the Creator sustains to his world after he has created it.

DR. BROMILEY: One or two additional things need also to be said. First of all, certain people have taken this view, of course, historically. Thomas Aquinas dealt with predestination or election under the heading of providence. And, in the period of the Reformation, Zwingli did also. He regarded predestination as one species, as it were, in the common genus of providence. My own feeling is against that, however. I think Barth’s criticism is extremely good. He thinks the relationship ought to be reversed, which would really come in his language very much to what you were saying, and what Dr. Nicole was saying. Providence is God’s overruling of his creation, but with a view to election, rather than the other way around (that election is a single part of the general providence). Therefore, election itself is the broader term, rather than providence. I tend to go with that, personally.

DR. HENRY: As we examine the debate over predestination and election in the narrower sense, on what points do all evangelical disputants agree, whether Arminian or Calvinist?

DR. NICOLE: Well, I would say that all agree that God is in fact sovereign. I am quite sure that the Arminian does not wish to deny that. He is often accused of doing it by the Calvinist, but I’m sure that he doesn’t want to do so.

DR. BROMILEY: I think all would relate the decrees or election or predestination of God to the saving work of Christ, although in different ways. But I think all would in fact agree that the election of God is fulfilled in or through Christ.

DR. WILEY: I would add also that we all believe in salvation by grace from beginning to ending, from the first dawn of salvation to final glorification.

DR. NICOLE: I want to add another item on which all agree—that man in this involvement is acting as a responsible agent and not as a robot. The Calvinist wishes to assert that, even though at times he gives the Arminian the impression that he doesn’t.

DR. WILEY: I think there is another likelihood of misunderstanding. We both believe in faith as the means of the acceptance of the gift of God—not faith as a substitute for righteousness, but faith as the exercise from the point of human helplessness, that gives all merit to Christ.

DR. HENRY: That faith is the appropriating means of salvation? The work of Christ is the ground of our salvation?

DR. WILEY: But no merit in faith! So many speak of Arminians as if we substitute faith for righteousness. We don’t believe that.

DR. HENRY: All agree also that not all men are saved, and that not all men will be saved—a significant point. Does this exhaust the areas of agreement?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, I think all would agree about the work of the Holy Spirit and the calling of believers, even though they may envisage the calling slightly differently. The universal offer of salvation is another point.

DR. NICOLE: And the general benevolence of God.

DR. BROMILEY: I’m not so sure all the Reformed really do.

DR. WILEY: We believe there is a continuity in grace.

DR. NICOLE: That is, if grace has once been given to someone, it will keep on being given?

DR. WILEY: No. We hold there is no distinction in the nature of grace between prevenient grace and saving grace; that it’s all of one nature. Consequently, we don’t draw the distinction, frequently drawn in Calvinism, between common and saving grace. We think one merges into the other.

DR. NICOLE: Well, at that point the Calvinist is not in agreement. That is a place where we disagree.

DR. BROMILEY: Karl Barth would cut right across all these distinctions of subdivisions of grace, which he thinks really were carried forward into the Protestant discussions out of Romanism. He would relate the grace of God more strictly to Christ himself, in his own person. In that sense he would be forced, of course, to hold to continuity, not in the sense in which it was mentioned, but to a unity of grace.

DR. WILEY: Can we all agree that Christ is really the elect?

DR. BROMILEY: That is a Barthian note. I don’t know that the Arminians actually have this.

DR. WILEY: Arminians stress and Ephesians teaches that we are predestinated as the children of God by Jesus Christ. I look at Christ as really the seed. He is in a sense the seed to which all others are gathered.

DR. HENRY: This would be held by all, that election is in Christ?

DR. NICOLE: Some supralapsarians [SUPRALAPSARIAN: one who holds that God’s decree of election determined that all men should fall, as instrumental to the redemption of certain individuals.—ED.] don’t share that view. Some say that election is prior even to any thought of redemption, and therefore that it would not be in Christ. So the passage in Ephesians about election in Christ would have to be explained by them with respect to some other decree.

DR. HENRY: Barth is a supralapsarian, is he not? And yet he says that election is in Christ.

DR. BROMILEY: Well, he takes the very simple view that Christ is in the beginning of all the ways and works of God, and therefore you cannot possibly have anything that is prior to Christ. He also bases this on the Scriptures, on a twofold point—that Christ is in fact the elect according to the express statements of Isaiah, and also that Christ himself being the substitute is necessarily the elect. Otherwise, there is no genuine substitution.

DR. HENRY: By pushing Christ in this way into all the works and activities of God, does Barth place Satan, death and hell in Christ also?

DR. BROMILEY: No, because they are not the ways and works of God.

DR. HENRY: On the supralapsarian view?

DR. BROMILEY: Not in the sense that God positively wills them. They are willed by God only in a negative way, not in a positive way. Otherwise God is the author of sin—if sin is willed in the same sense that the good creature of God is willed.

DR. WILEY: But Christ is made a reprobate.

DR. BROMILEY: Ah, yes, but that was for us, taking the place of the sinner, you see. It’s not directly that he is willed as himself a sinner, but he is willed as a substitute of the sinner, who takes to himself the reprobation of the sinner. And the reprobation is the judgment positively willed by God in exercising his righteousness.

DR. HENRY: Looking beyond the earlier areas of agreement, what formulation seems objectionable to each of us? Dr. Wiley, what about the Calvinistic formulation?

DR. WILEY: Well, I object to both the ‘supra’ and sublapsarian (or infralapsarian) views. [SUBLAPSARIAN: one who holds that God’s decree of election presupposes the fall as past, and as providing redemption for certain individuals already in a fallen and guilty state.—ED.] We think that God elects people in Christ, but we do not think that he elects whether or not individuals should be in Christ. Christ says “If I be lifted up, I will draw all men unto me”—so that there is a universal call, and a universal atonement and a universal gift of the Spirit. But not picking out people, as to whether they can be saved or whether they can not (which is very strong in Calvin: some are to be saved through Christ, but others are to be reprobate. Calvin is emphatic, that to believe in the salvation of some means the reprobation of others). That God has determined beforehand whether some should be saved or not, applied to individuals, is objectionable, in that it doesn’t make possible the salvation of all men through Christ.

DR. HENRY: What don’t you like about this?

DR. WILEY: Well, I don’t think God does that. I think God has called all men to be saved, but only in Christ, and only those who reject are reprobate, and those who are in Christ are the elect.

DR. HENRY: Do you feel the position impairs the love of God?

DR. WILEY: It not only impairs God’s love, it impugns God’s justice, for him to decide—regardless of whether a man believes or not—whether he can, whether he will be saved. To me it is out of harmony with the whole tenor of Scripture.

DR. HENRY: And where do you think this Calvinistic doctrine of election leads?

DR. WILEY: Go back in history and you will find that following Jonathan Edwards’ great revival, based on preaching the sovereignty of God, people took the position, ‘Well, if I’m to be saved, I’ll be saved; if not, why bestir myself?” It led to discouragement in many cases, and to despair. Finney preached the other side. He tried to balance things, and had a great revival. Now I believe in the sovereignty of God; I think one of the greatest needs in the present day is to preach the sovereignty of God. But not that God elects some to be saved and others to be lost, but that all can come to him through Christ.

DR. NICOLE: I find it objectionable that in the Arminian position the ultimate issues seem to depend upon the choice of man rather than upon the choice of God. And it seems to me that both the Scriptures and a proper understanding of divine sovereignty demand that the choice be left with God rather than with man. Now, precisely throughout Scripture there is a strong emphasis upon this divine priority, even in choice—which is the principle manifested in various areas of life, and which is more particularly emphasized in connection with the specific matter of salvation. The other position, I fear, might lead, when not carefully guarded, to an emphasis upon man—his choosing, his willing, his reason—and ultimately may turn to humanism.

DR. WILEY: I think that Professor Nicole’s position reflects one of the great Calvinistic errors concerning Arminianism. The Arminian does not make salvation to rest upon the human will or upon human works. It rests on faith as the appropriating of a gift, the merit of which belongs solely to Christ and not to any human effort. Faith is not a work. Faith is the acceptance of something that comes as a gift; the merit is all of Christ.

DR. NICOLE: The choice is man’s.… It’s man’s choice.

DR. WILEY: No, it’s not a choice of man. It’s a gift of God—but it must be received in some way.

DR. NICOLE: Yes, but the reason some receive it, and others don’t, is no differentiation in the work of God with man, but rather in the acceptance of man.

DR. WILEY: Yes, if you mean that the failure to be saved is due to man’s own will and rejection of the grace of God. But we believe in prevenient grace. We believe that the very first dawn brings the awakenings of the Spirit, and from that comes conviction, conversion and repentance, saving faith. But it is all the work of the Spirit. Now, we believe that the power to believe is of God; the act of believing is necessarily our own. That is fundamental in our thinking. It is the work of the Spirit all the way. And that is only exercised at the point of human helplessness and lack of merit. Therefore salvation is all of God, all of grace. But there must be some way of appropriating it and that’s by faith.

DR. HENRY: Would you like to comment, Dr. Bromiley?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, I hold a kind of mediating position. The Church of England has never committed itself (of course, there were two or three representatives at Dort, but it didn’t really commit itself beyond its own confession, which doesn’t give any judgment on the specific issue of the seventeenth century). As against the Arminians, the criticism of the Reformed school seems fairly well founded. To me it seems to presume a freedom of the will (I’m not thinking now of philosophical freedom) which is not in fact real, in the sense of response to the things of God. We have to reckon with the genuine bondage of the sinful will in relation to the message of the Gospel. And it seems to me that Arminianism doesn’t reckon seriously enough with that. It almost presumes that this bondage is not so—and that man has the freedom either to respond or not to respond. And even though Arminius himself seems to have stated his position very cautiously, and even the Remonstrance didn’t give a very blatant statement, yet that is implicit in the Arminian position, and is almost inevitably bound to lead to the kind of Methodist Arminianism and to the even more liberal forms that we have known in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. That seems to me to be the great weakness of the Arminian position.

On the other hand, quite a few points of difficulty remain in the position taken up at Dort, in its attempt to answer that. I won’t do more than just specify them. First of all, their scriptural exegesis gives the impression of being strained. The passages in relation to the universality of the work of Christ seem to most people “explained away” rather than genuinely exegeted and expounded. Secondly, they seem to be rather preoccupied with the data of experience rather than the data of the Gospel. The appeal is always: we evidently see before us certain people who are saved, and certain who are not, and we have to expound this situation; rather than allowing their exposition really to be an exposition of the data of the Bible. Thirdly, there seems to me to be a preoccupation with the question of efficacy rather than of sufficiency, and that really means with the question of what happens in me rather than what happened in Christ. So that ultimately the Dort position leads in exactly the same direction as the Arminian—to a concentration upon individual believers or non-believers, rather than upon God himself and his saving work. This was not an intention on either side. But in fact they contribute to the broad stream which ultimately gives us the present alternatives. And it is noticeable that the Reformed churches, even where they have attempted to maintain their emphasis, have been vulnerable to the modernist movements, no less than other churches.

DR. HENRY: Has the opposing view in fact led historically where its critics feared it would, when spelled out consistently? Do you think, Dr. Wiley, that the Calvinistic view has actually ended up historically where Arminian theologians warned it would?

DR. WILEY: It leads to despair and destroys human initiative—as well as impugns God’s justice and impairs his love.

DR. HENRY: Actually, as you look out upon the Calvinistic movements, do you think they are characterized by this spiritual despair and lack of initiative? Or is there an initiative that reflects a dependence upon Scripture? Or would you grant that historically, Calvinism has not really led to those conclusions to which Arminian theologians say it consistently leads as a system?

DR. WILEY: Well, keep this in mind: what passes for Calvinism—like the Plymouth Brethren—is not Calvinism. It is Arminianized. The fact is, Presbyterianism in this country is Arminianized. Or you might call it modified Calvinism or modified Arminianism. Of course, the old Scottish Calvinism still holds to individual election. I think few folks today teach Calvinism.

DR. HENRY: Do the others hold that Arminianism historically has led to where, for example, Calvin, or at least the opponents of Arminianism in the councils, predicted that it would?

DR. NICOLE: Yes, I think it has precisely. I would have to acknowledge, however, that some Calvinistic churches have also departed from what I conceive to be ideal. But when you consider the Arminians in Holland as a group, there you have an abysmal departure.

DR. WILEY: They are really not Arminians, in the sense of Arminius, at all.

DR. NICOLE: But Arminius was worse in his beliefs than he was in his writings. And the Remonstrance was worse than Arminius’ belief, and Episcopius was worse than Arminius, and Limborch was worse than Episcopius! And from then on it was declension, and they were infiltrated by Socinianism. In England the Methodist movement also departed, and precisely at the point I mentioned. For instance, you have the old controversy with J. Agar Beet in which, in the interests of maintaining uniform treatment by God of all people, Beet was led to posit a possibility of salvation after death, and so on, and finally universalism. You have the movement of Methodism in America, and you get finally E. S. Brightman with his finite god. You have a denial even of foreknowledge in McCabe’s Divine Nescience of Future Contingencies. The emphasis upon human freedom is so strong that it more and more impairs the divine majesty. Now, I am wholly aware that there are evangelical Arminians who do not for a moment sanction these things. But the weight of logic prevails in due time and historically those fruits have been developed.

DR. WILEY: But, after all, wasn’t Unitarianism a reaction from New England Calvinism?

DR. NICOLE: Yes. I’m not trying to accuse somebody else from a standpoint of superiority. But if the question is, Do I think that the history of the Arminian movement has led to some things that I feared from the system of doctrine, the only answer I can give is yes.

DR. HENRY: As a church historian, Dr. Bromiley, how do you look at this?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, it is a very complex, historical question. On the one side, I think every Calvinist would have to acknowledge under sober judgment that in evangelism and missionary work he has been far surpassed by the type of movement that grew out of pietism. I don’t think in the face of the historical data any Calvinist could suggest that in the modern movement of evangelism and missionary enterprise he has really contributed to the same degree. I’m not trying to say he has done nothing. But it is doubtful that he has made a contribution similar to what he would regard as Arminian movements—though he may deplore the way they have done it and the results of it. Then secondly, of course, there is a certain measure of truth, you know, in the judgment that Calvinism—worked out in its pure sense—does not really lead to the kind of thing that we often associate with the Reformed or Calvinistic nations. In the Highlands of Scotland, for instance, although there is a certain amount of national temperament there, there are some instances from the last century of the type of thing that Dr. Wiley was speaking about. People became preoccupied with this question of their own personal standing in grace and were really “fit for nothing” in doing any active work for the Gospel or for anything else in ordinary life. And a good deal of the activism of the Calvinist nations is due to an infiltration of other elements—of moralistic elements and later Puritanism, for instance, often associated with the deistic tendency. So that we cannot glibly assume that because certain movements took place in Reformed countries, they were wholly fruits of Calvinism, as is often done by Calvinistic apologies. On the other hand, I think we have to say this in favor of the Calvinists, that the evangelistic and missionary movement of the last century was almost “easy game,” as it were, for liberalism, that the whole tendency of the evangelical movement in that century in its Arminian forms was towards the liberalism of the twentieth century. You can see that in its social work. You can see it in some of its missionary work. You can see it in a lot of its evangelism and its aftermath. So that, although they perhaps took the lead as one might expect in extending the universal offer of Christ, they tended to do so in such a way that the liberalism that we know is almost, so far as one can speak in that way, an inevitable historical consequence. After all, Schleiermacher was brought up in the pietistic circles, pietist of the pietists.

DR. HENRY: We have said that Calvinism has sometimes led to lack of missionary passion, to preoccupation with personal salvation, and perhaps to indifference to the ethical fruits of salvation. And that Arminianism has led to a concentration on social service, to sentimental notions of universal salvation, and so on. Do you think these objectionable fruits follow from Calvinism or Arminianism exclusively, or that these same results might follow from other contributing factors?

DR. WILEY: That thought has been in my mind. I don’t think that these things flow from either Calvinism or Arminianism. Well, take, for instance, the humanistic movement. I don’t know that that originated in Arminianism. I don’t believe latitudinarianism in England was a result of Arminianism at all. I grant Dr. Nicole that Calvinism as a rule is narrow in its views, and the old saying is “if you want to make a stream strong, you have to make it narrow.” But the idea of toleration has been associated with Arminianism too much.

DR. NICOLE: Well, it certainly would be precarious to isolate just one factor and say, this is the source of the whole situation. There are many factors that affect men, and in examining the origins of any particular movement it is wise to balance the various elements. However, I rather recognize Arminianism long before Arminius. Some of its dominant traits, in my judgment, are found in some phases of the Greek church; and in some of the teachings, although here in an exaggerated form, in Pelagius; and in the dominant movements of semi-Pelagianism that engulfed the Roman Catholic church; and in the Renaissance rather than the Reformation. Then right within the Reformation movement itself came Arminianism, and latitudinarianism in the Church of England and other elements of that kind. It may be bias, but I would recognize the stream in various places and correlate some of those phenomena as belonging to one basic factor. I recognize that probably many evangelical Arminians would take strong objection and feel that this is an arbitrary oversimplification, and that they want nothing in common with Pelagius.

DR. BROMILEY: There are many historical factors, so that the thing works itself out in different nations in different ways, and we can’t just oversimplify and say this comes from that. I would like here really to be a good Calvinist and to say: The source of all these perversions is the bondage of the mind and will of man. So that in every movement in the Church there is always that temptation or that pressure back to a Pelagian scheme, to put man in the place where Christ ought to be. And however carefully we guard against that, and sometimes by the very way in which we try to guard against it, we may in the long run help it forward in the next generation. Whether we are Arminians or Calvinists, we need to see that in the Scriptures God is always “the one who fills the picture” and we ourselves are related to him. Now the temptation to get away from that is equally strong in Arminianism and in historic Calvinism. So that through these historical movements and factors, we see always in the Church that reversion or inversion from a genuine objectivism to subjectivism. We can see it happening before us in our own day.

DR. HENRY: Was not Arminius really “more Calvinistic” than most Protestantism today, regardless of denomination?

DR. WILEY: Arminius was always Reformed. But he differed on the decrees.

DR. HENRY: Arminius held a view of human corruption, did he not, deeper than that in much contemporary American Protestant theology.

DR. BROMILEY: I think so. Unless you take the really strict Dort followers, I think that judgment would probably be true. The majority of American evangelicals or British evangelicals have more Arminian teaching than the actual statements that we have of the Remonstrance.

DR. HENRY: Would this be true also of the post-Niebuhrian views?… That despite the impact of Niebuhr on contemporary theology, and the so-called realistic theology, contemporary theology is nonetheless sub-Arminian in orientation?

DR. WILEY: If I understand you, I think that is quite right.

DR. NICOLE: Well, there are notable exceptions, like almost the whole Christian Reformed Church, and the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, and others. But if you take Christendom at large probably that would be true.

DR. BROMILEY: There are certain people on the Continent of whom that might not be true, of course. I’m thinking more specifically of English-speaking forms of evangelicalism. Some of the older tradition remain in the Church of England.

DR. HENRY: What of the Free Church in Scotland?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, they tend on the whole to take the historic position of Dort or the Westminster Confession, so it wouldn’t be true of them.

DR. HENRY: And, of course, a remnant in many American denominations retains these convictions. This question, then: What makes Niebuhrian thought sub-Arminian in its doctrine of corruption?

DR. BROMILEY: It seems to me that Niebuhr really reads off the history of man’s corruption from the data of history rather than from the Gospel. It is “very nice” that the Gospel happens to be in agreement with it. And therefore, Niebuhr’s view is just as strong or just as weak as history.

DR. HENRY: If Arminius were here, what would he say to contemporary theology?

DR. WILEY: Well, Arminius believed in total depravity as much as the Reformers. There is no difference there. Older Calvinism held that there has to be an impartation of life before there can be faith or repentance. Arminius would take the position of free grace. We hold to a prevenient grace given to all mankind. In some sense that is a mitigated depravity, but it doesn’t affect the nature of depravity. It simply means that God gives his Spirit to all people so that they can repent.

DR. NICOLE: I think we are asking in what respects even Arminius can give us a deeper sense of man’s depravity, and therefore a deeper sense of the urgency of the Gospel. About all I can say is, let’s read Arminius, and discover that even Arminius has more of a sense of depravity than many present-day theologians have.

DR. HENRY: And he did not have a superficial doctrine of the new birth—as is often preached today—simply in terms of the renewing work of the Holy Spirit, quite independently of any doctrine of imputation and justification. For, certainly, imputation and justification and the substitutionary and propitiatory work of Christ are essential to Arminian doctrine, are they not?

DR. BROMILEY: It seems to me that Arminius would say of the modern view that it really isn’t an exposition of the biblical doctrine. Arminius, rightly or wrongly, was attempting to state the biblical theology and quite honestly I suppose believed that he was doing just that. But I don’t think he would really find that in our modern sociological theologians.

DR. HENRY: We are saying that both Arminius and Calvin were biblical in intention, and this intention to bring themselves under the biblical norm holds a lesson for contemporary theology. Would it not be well now to orient the discussion of election itself to the question of a biblical basis? Let’s ask what biblical loyalties on the one hand commit us to our views, and create anxieties about alternative positions. I suppose, Dr. Wiley, that you would regard certain passages as the bulwark of the Arminian view.

DR. WILEY: I view election or predestination, of course, as a class; the elect are those who are in Christ. Ephesians states a purpose: we are chosen in Christ unto holiness and obedience. Then Paul gives the method, which is predestination—predestinated, adopted as children by Jesus Christ to himself. The Scriptures call individuals to a position of faith in Christ, and here I make somewhat of foreknowledge: Peter’s verse, “elect according to the foreknowledge of God through sanctification of the Spirit and belief of the truth unto obedience,” and so on. Romans says, “Those whom he foreknew, those he did predestinate; and those he predestinated, he called, and those he called, he justified, and those he justified, he glorified.” I take that, however, not as an essential string of causes but as an order. When I think of foreknowledge, I take the same position as Wesley and Calvin—that strictly speaking there is no foreknowledge and no after-knowledge with God. The only place I differ is that Calvin said no relation exists between foreknowledge and predestination, which I can’t share. I think God knows everything in a moment’s grasp. He doesn’t choose people because they are good. We don’t believe that. But I do think that he knows those who will believe in Christ. He sees their faith. As a result of that, his plan is that they be conformed to the image of Christ. I think the next step is the call, and then justification, and so on.

DR. HENRY: Let me reassure myself about your position. The doctrine of foreknowledge seems to me to raise essentially the same question as the doctrine of election in relationship to individuals in this respect, that prior to the moment of psychological determination on the part of the individual it ascribes to God certain knowledge of the future. Now, if this is involved in foreknowledge, must not all objection be removed to its presence in election?

DR. WILEY: We maintain that both belong to God, but that it is preposterous to represent one as dependent on the other. When we attribute foreknowledge to God, we mean that all things are perpetually before his eyes, so that to his knowledge nothing is future or past. All things are present in such a manner that he does not merely conceive of them from ideas formed in his mind but really beholds and sees them. And this foreknowledge extends to the whole world and to all creatures. Wesley takes the position that God foresees who will believe. And I think that view of foreknowledge is right.

DR. HENRY: You accept, then, the idea that God foreknows certain events prior to their determination by individuals, and that on the basis of this foreknowledge he elects them?

DR. WILEY: No, I don’t think he elects them on the basis of foreknowledge. I think he just knows who will believe, and those who believe will be the elect. We are not predestinated to life or death; we are predestinated to the adoption of children.

DR. HENRY: Suppose you indicate, Dr. Nicole, what you think is the biblical basis for the Reformed view of election.

DR. NICOLE: Well, it may be subdivided into two parts, as it were. There is a general trend in Scripture which indicates principles of divine government and divine action, giving a broad basis for the whole elective purpose. And then specific passages support precisely the view that God has chosen some to salvation and has bypassed the others and confined them to the damnation which they justly deserve in view of their sins. Shall I develop the latter part? It will be found mostly in the New Testament. “No man can come to me, except the Father, which hath sent me draw him” (John 6:44). A passage like John 15:16: “Ye have not chosen me, but I have chosen you, and ordained you.…” Or a passage like that in Acts: “As many as were ordained to eternal life believed” (13:48). In the whole of Romans 9 through 11—especially in chapter 9—the priority of the election to the commission of any particular acts is set forth with very strong emphasis. Ephesians 1:4 and 11 are very significant, where the election is particularly mentioned as according to the good pleasure of God’s will. The passages dealing with foreknowledge are not at all difficult to integrate, inasmuch as the term foreknowledge in Scripture does not have merely the connotation of advance information (which the term commonly has in nontheological language), but indicates God’s special choice coupled with affection. In the Hebrew-Greek Scriptures to know connotes much more than “to have intellectual perception” of a certain thing. Therefore in Romans 8:29, for instance, “For whom he did foreknow, he also did predestinate to be conformed to the image of his Son,” and so on, the sequence does not, in our judgment, connote that the ground of the predestination is advance information that God had that these men would believe, although, of course, he does obviously have knowledge of all events past, present, and future. And similarly, in Peter: “elect according to the foreknowledge of God,” here again the word foreknowledge would require more than merely an intellectual content.

DR. WILEY: Election is in Christ and election must take place through Christ, of course. But those in Christ are the elect. The point Arminians oppose is that God elects certain individuals to be in Christ and certain individuals not. For instance, take Matthew 8:11: “The Son of man is come to save that which was lost.” Now, that is entirely out of harmony with the idea that God wills some to be saved and some to be reprobate. “Even so, it is not the will of your Father which is in heaven that one of these little ones should perish.” Take John 3:16: “For God so loved the world,” and so on—that evidently refers to the world in general. “For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved.” Now, there is no room in there at all for God reprobating people. “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life.” And then he goes on to say: “Ye will not come to me that ye might have life.” There are many others. In II Corinthians, “We thus judge, that if one died for all, then were all dead: and that he died for all, that they which live should not henceforth live unto themselves, but unto him which died for them, and rose again.” In Galatians, “Who gave himself for our sins, that he might deliver us form this present evil world, according to the will of God and our Father.” In I Timothy, “Who will have all men to be saved, and to come unto the knowledge of the truth.… Who gave himself a ransom for all, to be testified in due time.” And in John, “He is the propitiation for our sins: and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world. And we have seen and do testify that the Father sent the Son to be the Saviour of the world.” And in Hebrews 2:9: “That he by the grace of God should taste death for every man.” In James, “Draw nigh to God, and he will draw nigh to you. Cleanse your hands, ye sinners; and purify your hearts, ye double-minded.” Now in Ephesians, “According as he hath chosen us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and without blame before him in love.” I don’t think it can mean anything but the purpose of God. “Having predestinated us unto the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself, according to the good pleasure of his will,” refers to the fact that his purpose is the adoption of children by Jesus Christ to himself and not that he is selecting individuals to be in Christ. I’ll grant to Dr. Nicole that there is an election to service, but no individual election to salvation. We think that all those Scriptures are against it.

DR. HENRY: On what general principles do Calvinists reply?

DR. NICOLE: Some of the verses indicate only the fulfillment of certain conditions which all the Calvinists grant are involved in the obtaining of salvation—like faith, or repentance, or drawing nigh unto God. But Calvinists insist that those people who actually fulfill these conditions do not operate “on their own,” as it were, but that they have been led by God’s specific grace, which is in this case, an elective grace.

DR. WILEY: That is what we call prevenient grace, you know.

DR. NICOLE: Yes. But we would say that it is a prevenient grace not uniformly given to all, but given to some by the appointment of God to the exception of the others.

DR. WILEY: This is what we disagree with in Calvinism.

DR. NICOLE: I accept wholeheartedly the position of Calvin.

DR. HENRY: HOW does Barth propose to meet these issues?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, of course, he agrees with the Arminian emphasis—as it was already stated in the Remonstrance statement—that we must see the election wholly in relation to Christ, which he also feels is left out by the Calvinists. They begin with the prior decree of God, which really has very little to do with Christ at all; Christ is merely “dragged in,” as it were, as an agent for the fulfillment of this decree, which is an absolute unknown decree, according to the Calvinistic interpretation. But Barth doesn’t think the Arminians can in fact fruitfully work out their position because of their Arminianism. He attempts to bring this Arminian thesis into a setting, as he would take it, of Reformed theology, as he claims was attempted by the Bremen delegation at the Synod of Dort, but which did not meet with the approval of the Synod. Now Barth really, in effect, is attempting in his own way—which I grant gives rise to a lot of problems that I don’t see that he has really solved—to work out the lead suggested by the Bremen delegation—election in Christ really taken absolutely seriously—but purged of its Arminian connotations. And he claims for various reasons that any attempt to work out a doctrine of predestination either in terms of an absolute unknown God or in terms merely of the efficacy in the individual believer is virtually to make of Christ simply an instrument, and therefore to deprive him of his proper place, his proper honor, his proper position—and so long as we do that, we are ultimately unbiblical, and are bound to finish with a futile controversy, because Christ is the center of the Scriptures.

DR. HENRY: But what difficulties and problems does Barth’s formulation give us?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, he has a twofold difficulty. On the one side, he has to steer clear of universalism, which is, of course, a pressing danger, if you have a universal objective atonement in the sense that he wants to develop it: a really strict doctrine of substitution linked with an actual elective will which in Christ would comprehend all. There is a very distinct pressure towards universalism.

DR. NICOLH: Which leads him to say, for instance, that all are justified and all are sanctified, by which he means all men?

DR. BROMILEY: He means by that that all are in the substitute, in Christ.

DR. NICOLE: In him they are all justified and all sanctified?

DR. BROMILEY: He doesn’t mean by that that everyone is necessarily saved—that is what he tries to avoid. But there is obviously pressure towards universalism if you work it out in that way. If you avoid universalism, you get the definite difficulty which he himself does in fact face and can’t solve, of the sovereignty of the work of the Spirit—how it is that some do in effect repent and believe and enter into Christ, and some (though we can’t say definitely who they are) presumably do not. And all he can really say on that score is to leave it in terms of John 3, “The wind bloweth where it listeth.” But that seems to bring one back really to this unknown sovereignty that he is trying to get rid of. That is the problem on the face of it.

DR. NICOLE: Does not Barth leave us with a disparity in design between the three persons of the trinity? The Son is the substitute for all, while the Holy Spirit applies redemption only to some?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, Barth tries to work out that objection. He has never really worked it out satisfactorily to my mind. He desperately wants to avoid leaving the decision with man. But he has tended to hint that the Holy Spirit gives man freedom in and through the preaching of the Gospel, and what man is left to do is simply to use the freedom which he is given. If he does not do that, then he simply remains in bondage. But if he uses a given freedom he does not in fact free himself. Barth seeks to work it out in those terms.

DR. NICOLE: The Son blows over all the world and the Spirit bloweth where it listeth!

DR. BROMILEY: Well, where the Gospel is preached the Spirit will in fact give life to the dead, and it is left for the individual either to use his freedom or simply not do so. In which case he cannot claim that he himself has really done anything that he was not given.

DR. WILEY: How do you, Dr. Nicole, bring those Scriptures together and hold that God created some to be reprobate and created some to be saved? Why all those Scriptures that say God willeth not the death of any, and so on?

DR. NICOLE: Well, this really brings us back to the main matter. I believe that before election is spoken of, it would be wise to talk about the common fall of man. I don’t think that God created man just for the purpose of having some people to damn. But I believe that God, having in his own decree, in his own counsel, determined to create and to permit the fall, has in the presence of this fallen humanity determined to select some people out of his own mercy (and not in view of merit or any foreseen action on their part) to redeem them in Jesus Christ and effectually to apply to them the benefits of salvation, and to bypass the others. And this is not an election of class; this is an election of individuals. Now, in view of that, certain Scriptures need careful exposition. Dr. Bromiley suggests that at times the Calvinist appears to have an artificial explanation, and I concede that some Scriptures taken in themselves can be interpreted in a different way. But under the pressure of the total context of the Scripture I am constrained to interpret them as I do, and I would not be loath to venture an interpretation of those passages.

DR. WILEY: But you really then are not supralapsarian? You are really ‘sub’ or ‘infra’?

DR. NICOLE: That is correct. I am.

DR. WILEY: But I think you admit, though, that Calvin was supralapsarian?

DR. NICOLE: Well, I think there is a live issue at that point.

DR. WILEY: I have tended all the time to hold that Calvin was not supralapsarian. You don’t put the decree to elect ahead of the decree to create?

DR. NICOLE: That is correct. I do not. I say, first the decree to create, second the decree to permit the fall, third, the decree to elect and reprove.

DR. WILEY: I know, that is the position of the Synod of Dort.

DR. NICOLE: The Synod of Dort, I think, encouraged infralapsarianism, however, without specifically condemning supralapsarianism. But then they did rebuke Maccovius, a very strong supralapsarian, and asked him to speak with the Scriptures rather than with Aristotle.

DR. HENRY: If the unchurched masses tonight were to overhear our discussion, they might weary of it and think it quite irrelevant to the crisis in contemporary life and thought. What is so urgent about this theological dispute that led to diverse theological traditions, to many feelings and divisions? To what does this discussion of election and predestination call the modern man in his searching of the religious problem?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, it seems to me—if you’re thinking in terms of the masses—that the great things highlighted by this discussion are the helplessness of man without the grace of God, and the utter dependence of man for salvation, no matter who he is, upon God’s saving action in Jesus Christ. That is brought to a head by this whole discussion, and I think is ultimately the real relevance of it quite apart from any particular conclusions reached in the immediate setting. For the more educated world, which in a sense constitutes an even bigger problem than the masses, it seems to me that the great lesson for a true knowledge of God, for a true salvation by God, is this helplessness of man, in the first instance, and this need for the sovereign operation of God from first to last, from his seeking us to save, from his working out of salvation in the substitutionary death of Christ, and also through to the application of the message of the Gospel by the Holy Spirit under the means of grace. Now, of course, the modern man wouldn’t understand all this kind of terminology, but this is the lesson that we have to get across to him. And I think in this particular respect, classical Arminianism would not really be so far amiss as to the whole issue if it understood the task really in terms of getting this lesson in clear focus—although unfortunately it didn’t agree on what focus it should be. The whole of our modern world, both the masses and the educated, are in precise need of this particular message.

DR. WILEY: Well, I’m entirely agreed that man is helpless in himself for salvation and can’t be saved except by the grace of God from start to finish. When he believes in Christ, faith is not a substitute for righteousness; it is a means of appropriation, and all the merit accrues to Christ. Those that are brought into Christ are the elect in Christ. And I think, as far as talking about the rest of it, we are going back somewhat into the nature of God, and taking up a lot of things in which our difference is solely in terminology. But as long as we hold that man is depraved, man can’t be saved except by the grace of God, and that grace by the drawing of Christ. We live by grace and by faith all the way through. And finally, we shall be translated by grace.

DR. NICOLE: I certainly agree with the other brethren that the helplessness of man is to be emphasized at this time. And that message, while not pleasant to hear, is certainly readily understood. Also it is very important to emphasize the adequacy of the plan of God in the work of grace, and at that point particularly I think all of us can agree. Now, with respect to relevancy, I think that many of these problems do concern people. Whenever you start talking about predestination you get a lively discussion in almost any group. You don’t have to move with intellectuals to get an interest in that. In fact, it is relevant to philosophy, to other religions than the Christian one—the Moslem has almost as many discussions on this type of problem as we do. I cannot feel at all, when I discuss this matter, that I have estranged myself from the proper values of earthly existence. I feel, on the contrary, that this is very relevant. It is true that we must have a proper sense of reverence because we cannot delve curiously into the secrets of the Almighty. At the same time, this line of discussion is justified, is necessitated by the very conditions of our faith, and it presents vital issues that in some ways will form and fashion our proclamation of the gospel of Christ.

DR. HENRY: Can we locate one reason for the modern man’s feeling that predestination is once again a relevant consideration in the naturalistic and behavioristic philosophies that suggested a certain fatalistic destiny for man? That communism, as it were, also suggests that we are “predestined” to a given future? Does this context of contemporary philosophical discussion really help men detect in the gospel of Christ by contrast, despite the judgment it pronounces upon him, some glimmer of hope not found in the despairing philosophies of the day?

DR. BROMILEY: Well, I think it may raise an interest, but the Christian theologian has very sharply to differentiate the Gospel of grace from any kind of determinism of a materialistic or scientific nature. I think it is a fatal temptation to try to use these, as a few people have done, to back up the Christian doctrine or even to make some kind of transition to it, just as there was once a fatal tendency, or at least the Lutherans thought so, and some of the Reformed, to appeal to Islam. Many Lutherans in the seventeenth century thought that Calvinists were secret Mohammedans—quite wrongly, of course. Some of them finished up as deists, however. And they were deterministic. It seems to me we must resist the temptation to use these kinds of determinism as a form of bridge for the modern mind. At the same time, they have no doubt stimulated the question to which we can reply with the true doctrine of ordination or determination in a Christian setting.

We Quote:

DICKERING WITH DESPOTS: “As authentic freemen we are under profound moral compulsions to seriously hold onto and defend our deepest convictions.

“When expediences sink things into desperation, further bargaining with evil only speeds up the decimating processes. Free world leadership in conferences with recreant influences—parleying with the Hitlers of history—is more than a pathetic spectacle.… The dickering processes give communism a chance, not only to bleed “propaganda advantages” out of the moral weaknesses of Western civilization, but to advertise these moral weaknesses to a watching and terribly frightened human world. A still yet more fearful thing is that it plays havoc with hope. The people under the heel of Brutalitarianism grow sick at heart to see their slave masters respectfully consorted with by the representatives of the Free World. They know and we know and everybody knows that any agreement—no matter how solemnly signed—by such irresponsible faithlessness is completely worthless. “In its 40-year history the Soviet Union has executed over 2,000 agreements with non-communist governments” (Congressman Hosmer). None of them has been kept in good faith.…

“In the name of idealism the democracies go to the conferences hoping against hope that some humane considerations will prevail. With set and fixed intentions the communists go to the conferences to establish another position in the never ending use of “the big lie” to promote their grasp for world control. Here as always the deceptions about their methods are themselves a conniving and basic method for befuddling the people. This is why it sucks into its ranks of naive helpers so many men of good will. Conferences hoping to wheedle moral goodness out of such evils merely help degradation to play its ugly and terrible game.

“This era—of all eras—should not be blind. We refused to understand Mein Kampf and we paid dearly. Can we afford to repeat the failure with still yet more horrifying forces at work in the world? International conferences with those who are specialists in cynical irresponsibility may produce “double-talk” but they cannot produce moral greatness—and we need moral greatness, stubborn, unbending, unmitigated moral greatness. If ethical leadership in Western Civilization falls for the fiction it can buy peace by gambling with moral principles the future of humanity is dark. It is a fearful thing for the Free World to accept criminal rulers into respectable society endowing them with an undeserved prestige and standing.… Authentic morality bitterly condemns butchers and butcheries. It cannot sit down and listen to or sign treaties with the enemies of mankind.

“To give even a semblance of respectability or recognition to inhumane elements is to be an accomplice in the wickedness. The best of intentions do not change the reality of ruthless fact. The degradation which is now destroying the world’s decency, reeling and drunk with its appetite for power, has, through the naivete of other people’s childish hopes, already achieved a measure of international recognition, which, with sweeping fanfare will further the reaches of its conquests and in just that proportion will undercut the respect of enslaved millions for the moral character of the Free World. Those in bondage, walled off in the black hopelessness of the iron-curtain areas, cannot, I think, see and hear what has happened without monstrous misgivings.”—Commander H. H. LIPPINCOTT, United States Navy (Retired).