Christianity has always been a missionary religion. At the close of his earthly ministry, our Lord commissioned his followers to go and make disciples of all nations (Matt. 28:19), and it is generally admitted today that the Church of later generations has no right to call herself apostolic unless she acknowledges this missionary obligation to be her own. Now, the universal missionary imperative implies an exclusive claim, a claim made by our Lord himself: “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me” (John 14:6). To deny that men can know the Father apart from Christ is to affirm that non-Christian religion is powerless to bring them to God and effective only to keep them from him.

ONLY ONE SAVING RELIGION

Accordingly, the summons to put faith in Christ must involve a demand for the endorsement of this adverse verdict, and for the avowed renunciation of non-Christian faith as empty and, indeed, demonic falsehood. “Turn from these vanities to the living God” (Acts 14:15)—that was what the Gospel meant for those who worshiped the Greek pantheon at Lystra in Paul’s day, and that is what it means for the adherents of non-Christian religions now. The Gospel calls their worship idolatry (1 Thess. 1:9) and their deities demons (1 Cor. 10:20), and asks them to accept this evaluation as part of their repentance and faith.

And this point must be constantly and obtrusively made; for to play down the impotence of non-Christian religion would obscure the glory of Christ as the only Saviour of men. “There is none other name under heaven … whereby we must be saved” (Acts 4:12). If Christless religion can save, the Incarnation and Atonement were superfluous. Only, therefore, as the Church insists that Christless religion, of whatever shape or form, is soteriologically bankrupt can it avoid seeming to countenance the suspicion that for some people, at any rate, our Lord’s death was really needless.

WHAT OF OTHER RELIGIONS?

It is beyond dispute that this is the biblical position, but naturally it raises questions. How does the Gospel evaluate the religions which it seeks to displace? How, in view of its condemnation of them, does it account for the moral and intellectual achievements of their piety and theology? And how does it propose to set about commending Christ to the sincere and convinced adherents of the religions it denounces, without giving an impression of ignorance, intolerance, patronage, or conceit?

These questions press more acutely today than at any time since the Reformation, and there are three reasons for this. In the first place, a century’s intensive study of comparative religion has made available more knowledge than the Church ever had before about the non-Christian faiths of the world, and in particular of the intellectual and mystical strength of the highest forms of Eastern religion. This makes it necessary at least to qualify the sweeping dismissal of these faiths as ugly superstitions which to earlier missionary thinkers, who knew only the seamy side of Eastern popular piety, seemed almost axiomatic. Fair dealing is a Christian duty, and everybody of opinion has a right to be assessed by its best representatives as well as its worst. (How would historic Christianity fare if measured solely by popular piety down the ages?)

In the second place, the great Asian faiths are reviving and gaining ground partly, no doubt, through the impetus given them by upsurging nationalism. It is no longer possible naively to assume, as our evangelical grandfathers often did, that these religions must soon wither and die as the Gospel advances. As we meet them today, they are not moribund, but confident, aggressive, and forward-looking, critical of Christian ideas and convinced of their own superiority. How are we to speak to their present condition?

In the third place, Christian evangelism has been accused, and to some extent convicted, by Eastern spokesmen in particular of having in the past formed part of a larger cultural, and sometimes imperialistic, program of “Westernization.” These thinkers now tend to dismiss Christianity as a distinctively Western faith and its exclusive claim as one more case of Western cultural arrogance, and to insist that the present aspirations of the East are compatible only with indigenous Eastern forms of religion. There seems no doubt that Protestant missionary policy during the last hundred years really has invited this tragic misunderstanding. Too often it did in fact proceed on the unquestioned assumption that to export the outward forms of Western civilization was part of the missionary’s task, and that indigenous churches should be given no more than colonial status in relation to the mother church from which the missionaries had come. It is not surprising that such a policy has been both misunderstood and resented. The Protestant missionary enterprise needs urgently to learn to explain itself to the new nations in a way that makes clear it is not part of a cunning plan for exporting the British or American way of life, but is something quite different. This necessitates a reappraisal on our part of non-Christian religions which will be, if not less critical in conclusions, more sympathetic, respectful, and theologically discriminating in method than was the case in earlier days. Christian missionary enterprise inevitably gives offense to those of other faiths simply by existing; but the Church must watch to see that the offense given is always that of the Cross and never of fancied cultural snobbery and imperialism of the missionaries.

It seems that the need for a deepening of accuracy and respect in the evangelistic dialogue with other religions is more pressing than evangelical Christians generally realize. This, perhaps, is because evangelical missionary effort during the past fifty years has been channelled largely through small inter-(or un-) denominational societies which have concentrated on pioneer and village work, whereas it is in the towns that resentment and suspicion of the missionary movement are strongest. But it is very desirable that evangelicals should appreciate the situation and labor to give the necessary lead. They are uniquely qualified to do this, having been preserved from the confusion about the relation of Christianity to other religions which has clouded the greater part of Protestant thinking since the heydey of liberalism fifty years ago. Though liberalism is now generally disavowed, its ideas still have influence; and its ideas on this particular subject are the reverse of helpful, as we shall now see.

LIBERAL BIAS LINGERS

The liberal philosophy (you could not call it a theology) of religion was built on two connected principles, both of which have a pedigree going back to the philosophical idealism of Hegel and the religious romanticism of Schleiermacher. The first principle was that the essence of religion is the same everywhere: that religion is a genus wherein each particular religion is a more or less highly developed species. This idea was usually linked with the reading of man’s religious history as a record of ascent from animistic magical rites through ritualistic polytheism to the heights of ethical monotheism—a specious speculative schematization, the evolutionary shape of which gave it a vogue much greater than the evidence for it warrants. (In fact, the evidence for primitive monotheism, and for cyclic degeneration as the real pattern of mankind’s religious history, seems a good deal stronger. Romans 1:18–32 cannot now be dismissed as scientifically groundless fantasy.)

The second principle, following from the first, was that creeds and dogmas are no more than the epiphenomena of moral and mystical experience, attempts to express religious intuitions verbally in order to induce similar experiences in others. Theological differences between religions, or within a single religion, therefore, can have no ultimate significance. All religion grows out of an intuition, more or less pure and deep, of the same infinite. All religions are climbing the same mountain to the seat of the same transcendent Being. The most that can be said of their differences is that they are going up by different routes, some of which appear less direct and may not reach quite to the top.

If these ideas are accepted, the only question that can be asked when two religions meet is: Which of these is the higher and more perfect specimen of its kind? And this question is to be answered by comparing, not their doctrines, but their piety and the characteristic religious experiences which their piety enshrines. For religions are not the sort of things that are true or false, nor are their doctrines more than their by-products. Nor, indeed, has any existing form of religion more than a relative validity; the best religion yet may still be superseded by a worthier. Accordingly, the only possible justification for Christian missions is that Christians, whose piety and ethics represent the highest in religion that has emerged to date, are bound by the rule of charity to share their possessions with men of other faiths, not in order to displace those faiths, but to enrich them and (doubtless) to be enriched by them. And from this pooling of religious experience a still higher form of religion may well be developed. This position was expounded at the academic level by Troeltsch and on the popular level in such a document as the American laymen’s inquiry, Rethinking Missions (1931), which Hendrik Kraemer has described as “devoid of real theological sense … a total distortion of the Christian message,” involving “a suicide of missions and an annulment of the Christian faith” (Religionand the Christian Faith, 1956, p. 224). (This is just what J. Gresham Machen said when the report came out, but with less acceptance than Kraemer’s words command today.)

A CHANGE FOR THE BETTER

Since 1931, however, the theological atmosphere has changed for the better. The liberal philosophy of religions has been demolished by the broadsides of such writers as Barth, Brunner, and Kraemer himself, and attention is being given once again to the theology of religions found in the Bible.

What is this theology? It can be summed up in the following antithesis: Christianity is a religion of revelation received; all other faiths are religions of revelation denied. This we must briefly explain.

Christianity is a religion of revelation received. It is a religion of faith in a special revelation, given through specific historical events, of salvation for sinners. The object of Christian faith is the Creator’s disclosure of himself as triune Saviour of his guilty creatures through the mediation of Jesus Christ, the Father’s Word and Son. This is a disclosure authoritatively reported and interpreted in the God-inspired pages of Holy Scripture. Faith is trust in the Christ of history who is the Christ of the Bible. The revelation which the Gospel declares and faith receives is God’s gracious answer to the question of human sin. Its purpose is to restore guilty rebels to fellowship with their Maker. Faith in Christ is no less God’s gift than is the Christ of faith; the faith which receives Christ is created in fallen men by the sovereign work of the Spirit, restoring spiritual sight to their blind minds. Thus true Christian faith is an adoring acknowledgment of the omnipotent mercy of God both in providing a perfect Saviour for hopeless, helpless sinners and in drawing them to him.

Non-Christian religions, however, are religions of revelation denied. They are religions which spring from the suppression and distortion of a general revelation given through man’s knowledge of God’s world concerning the being and law of the Creator. The locus classicus on this is Romans 1:18–32; 2:12–15. Paul tells us that “the invisible things” of God—his diety and creative power—are not merely discernible but actually discerned (“God manifested” them; they “are clearly seen,” 1:19 f., ERV) by mankind; and this discernment brings knowledge of the obligation of worship and thanksgiving (vv. 20 f.), the duties of the moral law (2:14 f.), God’s wrath against ungodliness (1:18), and death as the penalty of sin (1:32). General revelation is adapted only to the needs of man in innocence and answers only the question: What does God require of his rational creatures? It speaks of wrath against sin but not of mercy for sinners. Hence it can bring nothing but disquiet to fallen man. But man prefers not to face it, labors to falsify it, and willfully perverts its truth into the lie of idolatry (1:25) by habitual lawlessness (1:18). Man is a worshiping being who has refused in his pride to worship his Maker; so he turns the light of divine revelation into the darkness of man-made religion, and enslaves himself to unworthy deities of his own devising, made in his own image or that of creatures inferior to himself (1:23). This is the biblical etiology of nonbiblical religion, from the crudest to the most refined.

FLASHES OF COMMON GRACE

Yet common grace prevents the truth from being utterly suppressed. Flashes of light break through which we should watch for and gratefully recognize (as did Paul at Athens when he quoted Aratus, Acts 17:28), and no part of general revelation is universally obscured. Despite all attempts to smother them, these truths keep seeping through the back of man’s mind, creating uneasiness and prompting fresh efforts to blanket the obtrusive light. Hence we may expect to find in all non-Christian religions certain characteristic recurring tensions, never really resolved. These are a restless sense of the hostility of the powers of the universe; an undefined feeling of guilt, and all sorts of merit-making techniques designed to get rid of it; a dread of death, and a consuming anxiety to feel that one has conquered it; forms of worship aimed at once to placate, bribe, and control the gods, and to make them keep their distance except when wanted; an alarming readiness to call moral evil good, and good evil, in the name of religion; an ambivalent attitude of mind which seems both to seek God and to seek to evade him in the same act.

Therefore, in our evangelistic dialogue with non-Christian religions, our task must be to present the biblical revelation of God in Christ not as supplementing them but as explaining their existence, exposing their errors, and judging their inadequacy. We shall measure them exclusively by what they say, or omit to say, about God and man’s relation to him. We shall labor to show the real problem of religion to which the Gospel gives the answer, namely, how a sinner may get right with his Maker. We shall diligently look for the hints and fragments of truth which these religions contain, and appeal to them (set in their proper theological perspective) as pointers to the true knowledge of God. And we shall do all this under a sense of compulsion (for Christ has sent us), in love (for non-Christians are our fellow-creatures, and without Christ they cannot be saved), and with all humility (for we are sinners ourselves, and there is nothing, no part of our message, not even our faith, which we have not received). So, with help from on high, we shall both honor God and bear testimony of him before men.

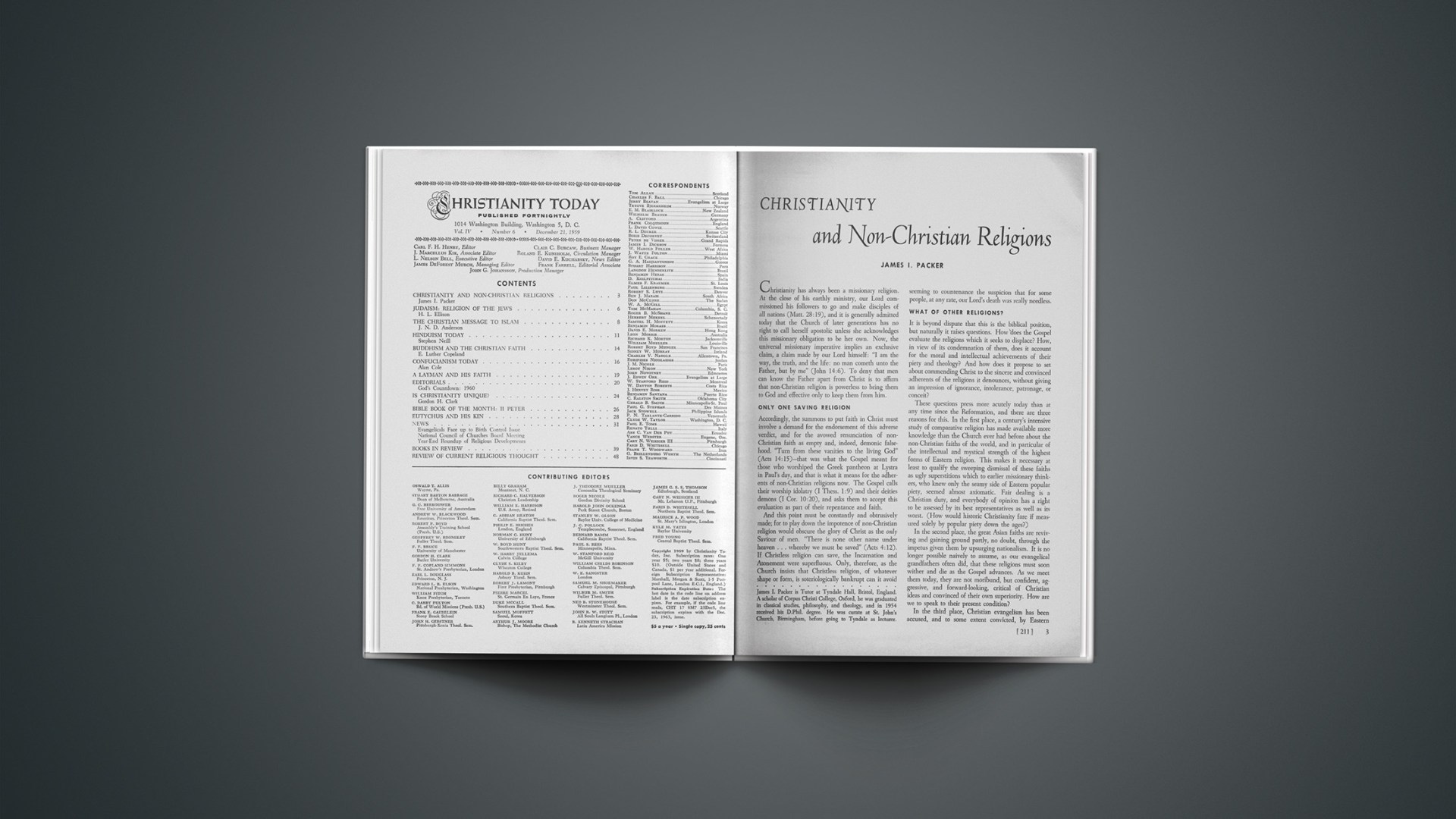

James I. Packer is Tutor at Tyndale Hall, Bristol, England. A scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, he was graduated in classical studies, philosophy, and theology, and in 1954 received his D.Phil. degree. He was curate at St. John’s Church, Birmingham, before going to Tyndale as lecturer.