Because of today’s emphasis on the missionary’s changing role and methods, the Church abroad may neglect her divinely entrusted task, may even overlook the unchanging validity of her God-given message. As never before, missionaries are involved in consultations and negotiations with government; in literacy and educational programs for nationals; and in changing socio-economic structures with heavy organizational and administrative pressures. Their prime responsibility remains, however, to assess all men and nations and cultures, from the perspective of Christian revelation, and to relay the evangelistic message of redemption in Christ Jesus. Small wonder that, over against a delinquent tendency to dismiss missions as an adjunct of the Church, as merely an optional concern, the clarion cry “the Church is mission” is now widely echoed.

If history’s next major event is not the Lord’s return—which believers in every generation hopefully anticipate—then the Church’s vast task becomes more awesome than ever. Not only the exploding world population, but mankind’s woefully misplaced loyalties as well, confront the missionary venture. Godless communism lunges for global conquest. Pagan religions are on the march. Mohammedanism in fact now claims to have in Africa alone more missionaries than Protestantism has in all the world. Buddhists are expanding and adapting their program, setting Buddhist doctrines to Christian hymnody (for example, “Buddha loves me, this I know”). By systematic revision the Hindu sacred writings are being made intelligible to the masses. Already building bigger shrines, Shintoism in the next decade hopes to restore emperor worship to Japan. Roman Catholicism with all its aberrations is maneuvering again to speak for a reunited Christendom. The cults Jehovah’s Witnesses and Mormonism are surging ahead with new life.

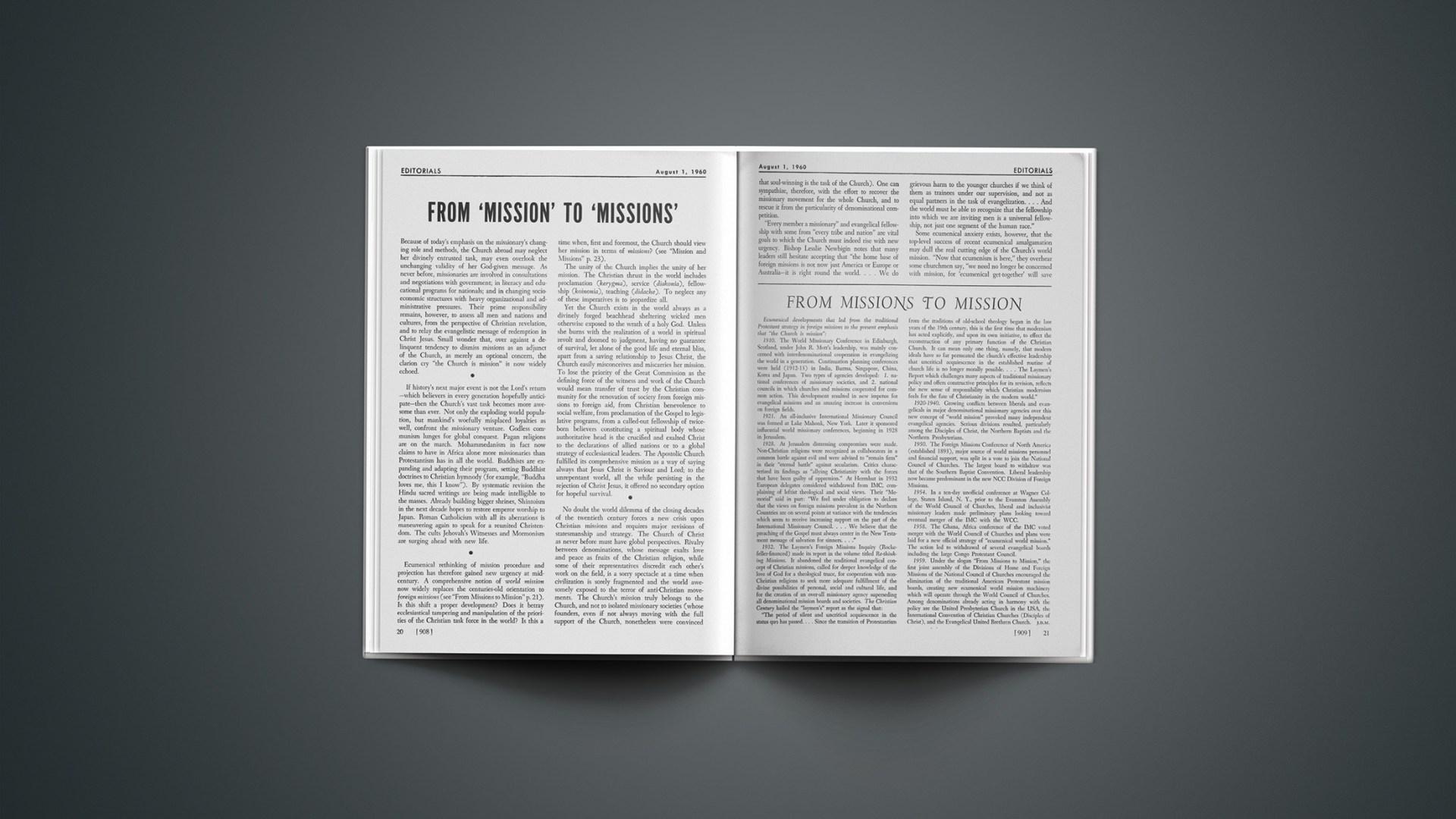

Ecumenical rethinking of mission procedure and projection has therefore gained new urgency at midcentury. A comprehensive notion of world mission now widely replaces the centuries-old orientation to foreign missions (see “From Missions to Mission” p. 21). Is this shift a proper development? Does it betray ecclesiastical tampering and manipulation of the priorities of the Christian task force in the world? Is this a time when, first and foremost, the Church should view her mission in terms of missions? (see “Mission and Missions” p. 23).

The unity of the Church implies the unity of her mission. The Christian thrust in the world includes proclamation (kerygma), service (diakonia), fellowship (koinonia), teaching (didache). To neglect any of these imperatives is to jeopardize all.

Yet the Church exists in the world always as a divinely forged beachhead sheltering wicked men otherwise exposed to the wrath of a holy God. Unless she bums with the realization of a world in spiritual revolt and doomed to judgment, having no guarantee of survival, let alone of the good life and eternal bliss, apart from a saving relationship to Jesus Christ, the Church easily misconceives and miscarries her mission. To lose the priority of the Great Commission as the defining force of the witness and work of the Church would mean transfer of trust by the Christian community for the renovation of society from foreign missions to foreign aid, from Christian benevolence to social welfare, from proclamation of the Gospel to legislative programs, from a called-out fellowship of twice-born believers constituting a spiritual body whose authoritative head is the crucified and exalted Christ to the declarations of allied nations or to a global strategy of ecclesiastical leaders. The Apostolic Church fulfilled its comprehensive mission as a way of saying always that Jesus Christ is Saviour and Lord; to the unrepentant world, all the while persisting in the rejection of Christ Jesus, it offered no secondary option for hopeful survival.

No doubt the world dilemma of the closing decades of the twentieth century forces a new crisis upon Christian missions and requires major revisions of statesmanship and strategy. The Church of Christ as never before must have global perspectives. Rivalry between denominations, whose message exalts love and peace as fruits of the Christian religion, while some of their representatives discredit each other’s work on the field, is a sorry spectacle at a time when civilization is sorely fragmented and the world awesomely exposed to the terror of anti-Christian movements. The Church’s mission truly belongs to the Church, and not to isolated missionary societies (whose founders, even if not always moving with the full support of the Church, nonetheless were convinced that soul-winning is the task of the Church). One can sympathize, therefore, with the effort to recover the missionary movement for the whole Church, and to rescue it from the particularity of denominational competition.

“Every member a missionary” and evangelical fellowship with some from “every tribe and nation” are vital goals to which the Church must indeed rise with new urgency. Bishop Lesslie Newbigin notes that many leaders still hesitate accepting that “the home base of foreign missions is not now just America or Europe or Australia—it is right round the world.… We do grievous harm to the younger churches if we think of them as trainees under our supervision, and not as equal partners in the task of evangelization.… And the world must be able to recognize that the fellowship into which we are inviting men is a universal fellowship, not just one segment of the human race.”

Some ecumenical anxiety exists, however, that the top-level success of recent ecumenical amalgamation may dull the real cutting edge of the Church’s world mission. “Now that ecumenism is here,” they overhear some churchmen say, “we need no longer be concerned with mission, for ‘ecumenical get-together’ will save the world.” Much of the drive for WCC-IMC merger is spurred, in fact, by certain ecumenists convinced that the rescue of the ecumenical movement from preoccupation with structural and organizational concerns depends upon shifting emphasis from unity of doctrine or order (highly provocative as these themes are) to unity in mission. Not truth, not structure, but saving deed or act (“the Church is mission”) is thought to hold promise of unity in depth. In the apostolic age, however, the Christian community was taught to glory simultaneously in “one Lord, one faith, one baptism,” and not simply in her world mission.

The new emphasis on mission is therefore a corollary of ecumenical stress on church unity. Its controlling assumption, regrettably, seems to be that the modern ecumenical movement (the soon-to-be integrated WCC and IMC) supplies the framework within which Christian activity becomes proper and legitimate (and perhaps even exclusively authentic). Intentionally or not, it casts suspicion upon missionary activity unidentified with WCC agencies and unrelated to WCC goals, the Church’s task in the world being justified only in organizational relation to WCC as the authorized Protestant fountainhead. Because of the organizational skill of ecumenical forces, in not a few lands government leaders today recognize their framework exclusively as the official Protestant clearinghouse in those lands. Despite many thousands of non-affiliated missionaries, the movement thus enhances its claim to speak as a pan-Protestant voice in matters relating to government.

Ecumenical leaders are distressed by the growth, at home and abroad, of what they call non-ecumenical agencies and non-cooperating churches. More properly, we think, these are to be designated simply as non-WCC affiliated, since the great bulk of these efforts are in no sense isolationist-independent. Most are associated with larger denominational or interdenominational effort engaged in a cooperative evangelical thrust. The number of missionaries sent out by these bodies still exceeds the number from churches related to the Division of Foreign Missions of the NCC. This is not, as is sometimes thought, a quite recent development; the new framework of ecumenical mission is actually the “Johnny-come-lately” to the missionary scene.

Ecumenical leaders disclaim any reflection on the authentic character of non-related activity. They stress, however, that the mission situation today differs from that of a century ago in this respect: “Not a single nation is without a church”; today there is “a worldwide Church.” The implications are, first, that nowhere can an autonomous missionary or church now be recognized; second, “sending” agencies must now clear with “receiving” lands (that is, the ecumenical organization in those lands). Yet in territories where non-affiliated evangelicals have long labored, having long precedence and numerical majority, ecumenical forces, assuming the superior status of their organization, seek (sometimes by intense propaganda and pressure) to bring unrelated efforts within their orbit. Promoting “the indivisible mission and strategy of the one Church,” they spur local and state councils of churches to new activities in home missions (frequently paralleling non-related efforts) and have multiplied ill will on numerous foreign fields as evidenced by the divisions provoked through the WCC-IMC merger drive in Ghana.

Has the New Testament concept of the Church as a body of regenerate believers whose head is the Risen Christ, and whose commission is to preach the Gospel of supernatural redemption to sinful men, given way to the ecumenical concept held by some that the true Church is WCC-affiliated? Overt identification with a twentieth century movement ought hardly to be made a criterion of continuity with the first century Church.

Beyond the proposed integration of IMC and WCC, does this movement look to a monolithic ecumenical Church? If we are really addressing the indivisible unity of the Church in biblical dimensions, is it permissible to call only for the transcending of “competitive” evangelical movements, and to assume the biblical justification for the National Council of Churches or World Council of Churches? If we really wish to recapture biblical perspectives, do we not need to transcend all peculiarly modern organizations and structures (what biblical basis is there, for example, for local councils of churches?) and return to the New Testament pattern—a regenerate Church united in spirit and doctrine, and concerned to fulfill its divine mandate to preach the Gospel to lost sinners? Given these facts, is not the enlargement of evangelical interrelationships to be welcomed rather than resented from a genuinely evangelical point of view? Is the goal of complete world evangelization actually achieved or necessarily advanced by merging of mission boards and organizational structures?

The cliché the Church is mission (itself objectionable, since mission is the task rather than the essence of the Church) unfortunately may serve so to revise the evangel that no longer does it center in the offer of supernatural regeneration to lost sinners, but accommodates a reliance (as especially in the National Council of Churches) on socio-political pronouncements and legislative programs as primary means of social change. The NCC by its related agencies has defended detailed pronouncements of social policy (involving such debatable commitments as support for Red China in the U.N.). Its record on doctrinal priorities has been ambivalent, however, and church councils show (as in Chicago and Philadelphia) a notable disinterest in mass evangelism. Some ecumenical spokesmen welcome the weakened link between a “sending” Church and a “receiving” country as detaching Christian mission from the political conflicts of our time, and urge the Church to “rise above” the conflict between East and West. The “revolutionary gospel” not infrequently is invoked in approval of revolutionaries who confiscate private property to rectify social injustices, or who support pacifism to frustrate military alliances with the West (as in Japan), or who scorn legal restrictions to force social reforms. Uneasiness therefore mounts at grass roots lest “from missions to mission” implies a basic reorientation of the nature and task of the Church in its bearing on socio-cultural issues.

The ecumenical ideal is by no means identical with the ecumenical movement in its current form, even though constructive criticism of the movement is often deplored by ecumenists as merely the ill wind of independency. The modern ecumenical movement assuredly offers us a theological interpretation of the world predicament. But is its interpretation adequately biblical? Or is it too much framed on prior assumptions that justify the inclusivist objectives of contemporary ecumenism, often more concerned with organization than with doctrinal integrity? Granted an adequately evangelical basis requires partnership between missions of different nations and races to reflect the universal character of the missionary operation; granted also that ecumenical spokesmen in 1960 reject as absurd and impossible the idea of “a global mission board which would undertake world-wide missions as one colossal operation,” does it follow that current ecumenical perspectives and structures mirror the realities of the Apostolic Church in the modern world? While the Church is going global in our day, it is not discernibly becoming more biblical. The word “ecumenical” has indeed become a symbol for theological conversation, ecclesiastical merger, programs of social action, but not for a biblical thrust in theology, evangelism, and missions. The great need is to recover the ecumenical ideal in biblical dimensions: to rise above the movements of modernity, to go even beyond the Church, and to find that Body’s true virtue and power and glory in her Risen Head.

From Missions To Mission

Ecumenical developments that led from the traditional Protestant strategy in foreign missions to the present emphasis that “the Church is mission”:

1910. The World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh, Scotland, under John R. Mott’s leadership, was mainly concerned with interdenominational cooperation in evangelizing the world in a generation. Continuation planning conferences were held (1912–13) in India, Burma, Singapore, China, Korea and Japan. Two types of agencies developed: 1. national conferences of missionary societies, and 2. national councils in which churches and missions cooperated for common action. This development resulted in new impetus for evangelical missions and an amazing increase in conversions on foreign fields.

1921. An all-inclusive International Missionary Council was formed at Lake Mahonk, New York. Later it sponsored influential world missionary conferences, beginning in 1928 in Jerusalem.

1928. At Jerusalem distressing compromises were made. Non-Christian religions were recognized as collaborators in a common battle against evil and were advised to “remain firm” in their “eternal battle” against secularism. Critics characterized its findings as “allying Christianity with the forces that have been guilty of oppression.” At Herrnhut in 1932 European delegates considered withdrawal from IMC, complaining of leftist theological and social views. Their “Memorial” said in part: ‘We feel under obligation to declare that the views on foreign missions prevalent in the Northern Countries are on several points at variance with the tendencies which seem to receive increasing support on the part of the International Missionary Council.… We believe that the preaching of the Gospel must always center in the New Testament message of salvation for sinners.…”

1932. The Laymen’s Foreign Missions Inquiry (Rockefeller-financed) made its report in the volume titled Re-thinking Missions. It abandoned the traditional evangelical concept of Christian missions, called for deeper knowledge of the love of God for a theological truce, for cooperation with non-Christian religions to seek more adequate fulfillment of the divine possibilities of personal, social and cultural life, and for the creation of an over-all missionary agency superseding all denominational mission boards and societies. The Christian Century hailed the “laymen’s” report as the signal that:

“The period of silent and uncritical acquiescence in the status quo has passed.… Since the transition of Protestantism from the traditions of old-school theology began in the late years of the 19th century, this is the first time that modernism has acted explicitly, and upon its own initiative, to effect the reconstruction of any primary function of the Christian Church. It can mean only one thing, namely, that modern ideals have so far permeated the church’s effective leadership that uncritical acquiescence in the established routine of church life is no longer morally possible.… The Laymen’s Report which challenges many aspects of traditional missionary policy and offers constructive principles for its revision, reflects the new sense of responsibility which Christian modernism feels for the fate of Christianity in the modern world.”

1920–1940. Growing conflicts between liberals and evangelicals in major denominational missionary agencies over this new concept of “world mission” provoked many independent evangelical agencies. Serious divisions resulted, particularly among the Disciples of Christ, the Northern Baptists and the Northern Presbyterians.

1950. The Foreign Missions Conference of North America (established 1893), major source of world missions personnel and financial support, was split in a vote to join the National Council of Churches. The largest board to withdraw was that of the Southern Baptist Convention. Liberal leadership now became predominant in the new NCC Division of Foreign Missions.

1954. In a ten-day unofficial conference at Wagner College, Staten Island, N. Y., prior to the Evanston Assembly of the World Council of Churches, liberal and inclusivist missionary leaders made preliminary plans looking toward eventual merger of the IMC with the WCC.

1958. The Ghana, Africa conference of the IMC voted merger with the World Council of Churches and plans were laid for a new official strategy of “ecumenical world mission.” The action led to withdrawal of several evangelical boards including the large Congo Protestant Council.

1959 Under the slogan “From Missions to Mission,” the first joint assembly of the Divisions of Home and Foreign Missions of the National Council of Churches encouraged the elimination of the traditional American Protestant mission boards, creating new ecumenical world mission machinery which will operate through the World Council of Churches. Among denominations already acting in harmony with the policy are the United Presbyterian Church in the USA, the International Convention of Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ), and the Evangelical United Brethren Church.

Mission And Missions

We have to begin making some verbal distinctions if we are going to have our thinking clear. The first is between mission and missions. When we speak of “the mission of the Church” we mean everything that the Church is sent into the world to do—preaching the Gospel, healing the sick, caring for the poor, teaching the children, improving international and interracial relations, attacking injustice—all of this and more can rightly be included in the phrase “the Mission of the Church.”

But within this totality there is a narrower concern which we usually speak of as “missions.” Let us, without being too refined, describe this narrower concern by saying: it is the concern that in the places where there are no Christians there should be Christians. And let us narrow the concern down still further and say that within the concept of missions there is the still narrower concern which we call—or used to call—Foreign Missions—which is the concern that Jesus should be acknowledged as Lord by the whole earth.

Now I am aware of the fact that what I am doing is unpopular at present. People say “Why make this artificial distinction? Why separate the foreign missionary from any other Christian doing any other job? Why not see the whole work of the Church as Mission? Let’s drop the old language about missions and missionaries and simply talk about the total Mission of the Church.”

There are two answers to this:

1. The first is that it is equally possible to take other words besides Mission and use them in the same way. It is possible to say that the whole work of the Church can be brought under the head of service (diakonia), or one can say that it is all evangelism, or that it is all stewardship, or that it is all worship. It is even possible to say that it is all education. A very good case can be made out of using every one of these words to cover the whole range of Christian existence. But when you have done so you have destroyed any possibility of dividing up the different functions in the economy of the Church for the practical purposes of its day-to-day life.

2. The second reason is that any progress in thought and action depends on being able to discern and state both the relation between things and the distinction between things. Or to put it another way, it depends upon being capable of looking at one thing at a time without thereby falling into the illusion of thinking that it is the only thing that exists.

Now it is my plea that if ecumenicity is not to mean Christianity without its cutting edge, one of our needs today is to identify and distinguish the specific foreign missionary task within the total Mission of the Church understood in ecumenical terms. Let me put my case in staccato form:

1. The foreign missionary task is the task of making Christ known as Lord and Saviour among those who do not so know Him, to the ends of the earth.

2. This task is not the whole of the Church’s Mission, but it is an essential part of it.

3. It is essential because the confession that Jesus Christ is Lord of all, and that His coming is the coming of the end of history for the whole human race, requires as its practical implicate the endeavor to make this faith known to the ends of the earth.

4. The home base of this foreign missions enterprise is wherever in the world the Church is. Every Church in the world, however small and weak, ought to have some share in the foreign missions enterprise. No Church adequately confesses Christ which is content to confess Him only among its own or immediate neighbors.

If there were time I could elaborate some of what these theses will mean in practice.…

It will mean—I think and hope—that we shall not be afraid to recognize and honor the vocation of the foreign missionary as a distinct calling among the many which God may address to us.… These recent years have been years of perplexity for the younger generation of foreign missionaries. The old simplicity and direction of the missionary call of the 19th Century has become confused. There are only a very few points of the world now where the missionary goes out simply to preach the Gospel to the heathen. He goes first to become part of the young Church and to help it in its witness. But what does he bring? What is his place? For a good many years now the answer has been that he brings some special qualification which the local Church is unable to provide. He is thus a kind of ecclesiastical analogue to the technical aid expert lent by one nation to another while the latter trains the men it needs. He is in fact a personalized form of inter-church aid and obviously he is temporary.

The conclusion would then seem to be that in a few years’ time we could withdraw all missionaries from India. The logic is impeccable. What is wrong is the starting point. The argument goes wrong because it starts from the Church and not from the world. While 97% of India remains non-Christian, and probably 80% out of touch with the Gospel, what is the missionary logic that can permit us to say “the task is done and missionaries can be withdrawn?”

It is the India Church itself which is challenging this way of thinking. More and more Indian Christian leaders are saying: the thing the missionary should bring us is not primarily his technical expertness; it is his missionary passion. We want missionaries above all to help us to go outside ourselves and bring Christ to our people.

This then is the picture of the missionary’s task today.… He is the indispensable personal expression of the duty and privilege of the whole Church in every land to take the whole Gospel of salvation to the whole world, and to prepare the world for the coming of its sovereign Lord.—From an address by the Right Reverend LESSLIE NEWBIGIN to the 172nd General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.

CHRISTIAN RESPONSIBILITY IN POLITICAL AFFAIRS

In view of the spreading lament over the drift from sound government and political morality, it is not amiss to remind the Christians of America of their citizenship in two worlds and their consequent civic responsibility.

Unless major political parties undergo continual ethical purification, they become corrupt. Spiritually-minded citizens ought to furnish the catalyst for the realignment of political interests around principle, and to spearhead the opposition to liberalizing views that dissolve national distinctives.

The problem is not simply that of the shameful indifference of the masses in our republic, but of leadership. To some of our politicians, a devout spiritual commitment seems a liability in a pluralistic society. The tendency to confine the significance of Christianity to the sphere of private devotion, moreover, blurs out the socio-political implications of biblical religion. And the absence of an organized constituency supportive of statesmen of a dedicated point of view often leaves such spokesmen vulnerably exposed to the machinations of organized pressure blocs.

We are going to need a comprehensive approach to the political drift in America. A good beginning is for each and every Protestant churchgoer to get active in one of the 150,000 precincts and learn how politics operates so he or she can become a factor in good government.

Needed is a depth of understanding, clarity of thought, and an evaluation of implications far beyond what is usually involved in a political campaign.

History, religious concepts, behind-the-scenes pressures, long-range plans of cohesive groups—all are a part of the issue, and in their rightful interpretation can lie the destiny of our nation. Blind partisan politics must yield to a higher allegiance.

CUBA SITUATION BECOMES A BATTLE FOR THE HEMISPHERE

While American foreign policy pursues its Antaean role of seeking strength by falling on its face, a little man who “plays the rumba on his tuba down in Cuba” has whipped up a Grade-A threat to our national security. Fidel Castro is now threatening to turn the Caribbean sea into a red lake.

We cannot help wondering what James Monroe or Teddy Roosevelt would have done in such circumstances. Can the United States tolerate, 90 miles off shore, a deadly enemy, bent on bringing in foreign powers that would destroy us? It is Castro’s evident design to turn the Western hemisphere into a Communist empire. There is no need to belabor the point; brother Raul did not go to Moscow for his health.

Fidel’s love affair with communism reminds one historically of the romance of the Stuarts with Roman Catholicism. Unswervingly they moved toward their goal, until England rose up and rebelled. Does the strategy of patience now require us to wait and watch while Castro carries out his design?

There are many people in Cuba today who have withstood the television barrage of hate, who know that we still regard them affectionately as friendly neighbors. How other Cubans could be mesmerized by an Animal Farm Napoleon into distrusting America is a tragic mystery, but it is also a fact facing every free man in the hemisphere. We have no designs on Cuba or any other part of the world. Neither do the American people intend to let Castro leak communism into the Caribbean. As Kipling would have said,

“The end of that game is oppression and shame,

And the nation that plays it is lost!”