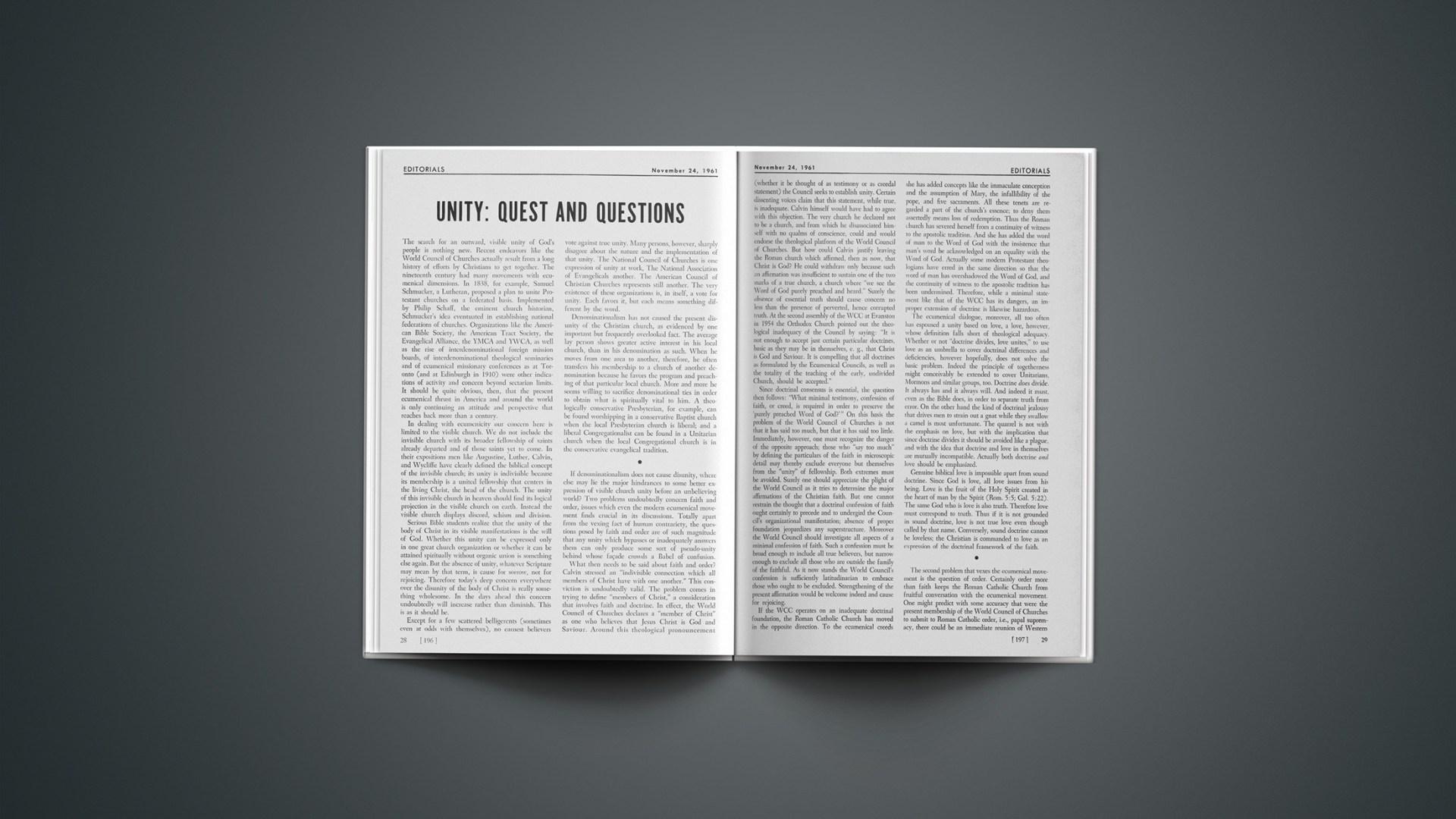

The search for an outward, visible unity of God’s people is nothing new. Recent endeavors like the World Council of Churches actually result from a long history of efforts by Christians to get together. The nineteenth century had many movements with ecumenical dimensions. In 1838, for example, Samuel Schmucker, a Lutheran, proposed a plan to unite Protestant churches on a federated basis. Implemented by Philip Schaff, the eminent church historian, Schmucker’s idea eventuated in establishing national federations of churches. Organizations like the American Bible Society, the American Tract Society, the Evangelical Alliance, the YMCA and YWCA, as well as the rise of interdenominational foreign mission boards, of interdenominational theological seminaries and of ecumenical missionary conferences as at Toronto (and at Edinburgh in 1910) were other indications of activity and concern beyond sectarian limits. It should be quite obvious, then, that the present ecumenical thrust in America and around the world is only continuing an attitude and perspective that reaches back more than a century.

In dealing with ecumenicity our concern here is limited to the visible church. We do not include the invisible church with its broader fellowship of saints already departed and of those saints yet to come. In their expositions men like Augustine, Luther, Calvin, and Wycliffe have clearly defined the biblical concept of the invisible church; its unity is indivisible because its membership is a united fellowship that centers in the living Christ, the head of the church. The unity of this invisible church in heaven should find its logical projection in the visible church on earth. Instead the visible church displays discord, schism and division.

Serious Bible students realize that the unity of the body of Christ in its visible manifestations is the will of God. Whether this unity can be expressed only in one great church organization or whether it can be attained spiritually without organic union is something else again. But the absence of unity, whatever Scripture may mean by that term, is cause for sorrow, not for rejoicing. Therefore today’s deep concern everywhere over the disunity of the body of Christ is really something wholesome. In the days ahead this concern undoubtedly will increase rather than diminish. This is as it should be.

Except for a few scattered belligerents (sometimes even at odds with themselves), no earnest believers vote against true unity. Many persons, however, sharply disagree about the nature and the implementation of that unity. The National Council of Churches is one expression of unity at work, The National Association of Evangelicals another. The American Council of Christian Churches represents still another. The very existence of these organizations is, in itself, a vote for unity. Each favors it, but each means something different by the word.

Denominationalism has not caused the present disunity of the Christian church, as evidenced by one important but frequently overlooked fact. The average lay person shows greater active interest in his local church, than in his denomination as such. When he moves from one area to another, therefore, he often transfers his membership to a church of another denomination because he favors the program and preaching of that particular local church. More and more he seems willing to sacrifice denominational ties in order to obtain what is spiritually vital to him. A theologically conservative Presbyterian, for example, can be found worshipping in a conservative Baptist church when the local Presbyterian church is liberal; and a liberal Congregationalist can be found in a Unitarian church when the local Congregational church is in the conservative evangelical tradition.

If denominationalism does not cause disunity, where else may lie the major hindrances to some better expression of visible church unity before an unbelieving world? Two problems undoubtedly concern faith and order, issues which even the modern ecumenical movement finds crucial in its discussions. Totally apart from the vexing fact of human contrariety, the questions posed by faith and order are of such magnitude that any unity which bypasses or inadequately answers them can only produce some sort of pseudo-unity behind whose facade crowds a Babel of confusion.

What then needs to be said about faith and order? Calvin stressed an “indivisible connection which all members of Christ have with one another.” This conviction is undoubtedly valid. The problem comes in trying to define “members of Christ,” a consideration that involves faith and doctrine. In effect, the World Council of Churches declares a “member of Christ” as one who believes that Jesus Christ is God and Saviour. Around this theological pronouncement (whether it be thought of as testimony or as creedal statement) the Council seeks to establish unity. Certain dissenting voices claim that this statement, while true, is inadequate. Calvin himself would have had to agree with this objection. The very church he declared not to be a church, and from which he disassociated himself with no qualms of conscience, could and would endorse the theological platform of the World Council of Churches. But how could Calvin justify leaving the Roman church which affirmed, then as now, that Christ is God? He could withdraw only because such an affirmation was insufficient to sustain one of the two marks of a true church, a church where “we see the Word of God purely preached and heard.” Surely the absence of essential truth should cause concern no less than the presence of perverted, hence corrupted truth. At the second assembly of the WCC at Evanston in 1954 the Orthodox Church pointed out the theological inadequacy of the Council by saying: “It is not enough to accept just certain particular doctrines, basic as they may be in themselves, e. g., that Christ is God and Saviour. It is compelling that all doctrines as formulated by the Ecumenical Councils, as well as the totality of the teaching of the early, undivided Church, should be accepted.”

Since doctrinal consensus is essential, the question then follows: “What minimal testimony, confession of faith, or creed, is required in order to preserve the ‘purely preached Word of God?’ ” On this basis the problem of the World Council of Churches is not that it has said too much, but that it has said too little. Immediately, however, one must recognize the danger of the opposite approach; those who “say too much” by defining the particulars of the faith in microscopic detail may thereby exclude everyone but themselves from the “unity” of fellowship. Both extremes must be avoided. Surely one should appreciate the plight of the World Council as it tries to determine the major affirmations of the Christian faith. But one cannot restrain the thought that a doctrinal confession of faith ought certainly to precede and to undergird the Council’s organizational manifestation; absence of proper foundation jeopardizes any superstructure. Moreover the World Council should investigate all aspects of a minimal confession of faith. Such a confession must be broad enough to include all true believers, but narrow enough to exclude all those who are outside the family of the faithful. As it now stands the World Council’s confession is sufficiently latitudinarian to embrace those who ought to be excluded. Strengthening of the present affirmation would be welcome indeed and cause for rejoicing.

If the WCC operates on an inadequate doctrinal foundation, the Roman Catholic Church has moved in the opposite direction. To the ecumenical creeds she has added concepts like the immaculate conception and the assumption of Mary, the infallibility of the pope, and five sacraments. All these tenets are regarded a part of the church’s essence; to deny them assertedly means loss of redemption. Thus the Roman church has severed herself from a continuity of witness to the apostolic tradition. And she has added the word of man to the Word of God with the insistence that man’s word be acknowledged on an equality with the Word of God. Actually some modern Protestant theologians have erred in the same direction so that the word of man has overshadowed the Word of God, and the continuity of witness to the apostolic tradition has been undermined. Therefore, while a minimal statement like that of the WCC has its dangers, an improper extension of doctrine is likewise hazardous.

The ecumenical dialogue, moreover, all too often has espoused a unity based on love, a love, however, whose definition falls short of theological adequacy. Whether or not “doctrine divides, love unites,” to use love as an umbrella to cover doctrinal differences and deficiencies, however hopefully, does not solve the basic problem. Indeed the principle of togetherness might conceivably be extended to cover Unitarian, Mormons and similar groups, too. Doctrine does divide. It always has and it always will. And indeed it must, even as the Bible does, in order to separate truth from error. On the other hand the kind of doctrinal jealousy that drives men to strain out a gnat while they swallow a camel is most unfortunate. The quarrel is not with the emphasis on love, but with the implication that since doctrine divides it should be avoided like a plague, and with the idea that doctrine and love in themselves are mutually incompatible. Actually both doctrine and love should be emphasized.

Genuine biblical love is impossible apart from sound doctrine. Since God is love, all love issues from his being. Love is the fruit of the Holy Spirit created in the heart of man by the Spirit (Rom. 5:5; Gal. 5:22). The same God who is love is also truth. Therefore love must correspond to truth. Thus if it is not grounded in sound doctrine, love is not true love even though called by that name. Conversely, sound doctrine cannot be loveless; the Christian is commanded to love as an expression of the doctrinal framework of the faith.

The second problem that vexes the ecumenical movement is the question of order. Certainly order more than faith keeps the Roman Catholic Church from fruitful conversation with the ecumenical movement. One might predict with some accuracy that were the present membership of the World Council of Churches to submit to Roman Catholic order, i.e., papal supremacy, there could be an immediate reunion of Western Christendom even though the Reformers viewed the papacy as the height of human pretension and disavowed the Roman Catholic Church as a true church. The episcopacy, or the right of holy orders, stands at the center of the problem of church order. Supporters of episcopacy cannot honestly acknowledge that those without benefit of ordination by bishops who stand in apostolic succession from the days of the apostles are to be accepted as ministers of the Gospel. And since the validity of the sacraments is inextricably bound to the person who superintends them there can be no valid baptism or celebration of the Eucharist by one who has not received holy orders via apostolic succession. For those in the tradition of apostolic succession to concede at this point would be to deny the heart of their establishment. Contrariwise for others to embrace the episcopal view would be to stress what they declare to be non-essential, if not opposed, to their views of the Christian faith. Whether the non-episcopal forces will bow to the episcopal view by way of concession rather than principle, and whether even this gesture would bridge the gap are still moot questions.

Discussions of church order, moreover, lead naturally to the question as to whether, on this subject, God’s Word lays down principles which are binding upon the churches. The importance of this question is obvious. If the Word of God specifically supports Congregational, or Presbyterial, or Episcopal ecclesiology, then any others must be in error and do not reflect the biblical norm. Furthermore, the people who embrace other ecclesiologies must be sinning and should therefore change. On the other hand, if the Word of God does not prescribe one particular form of church order but allows for free expression according to the genius and spiritual needs of God’s people, then denominations as we know them are not sinful. They are, rather, creative expressions of the sovereign working power of the Holy Spirit.

The future of unity depends in some measure at least, then, on the answers given to the aforementioned questions. Obviously the problems of faith and order will not be solved readily, for no one person or group has all the truth. But contemporary theology with its confusion and contradiction hardly provides as secure a basis for Christian togetherness as does faith rooted in God’s authoritative Word. However limited the perspective of any group or individual may be, certain conclusions cannot be disputed. 1. Because they have been baptized by the same Spirit those who are in Christ are indivisibly united. 2. Because they are thus joined they ought to be able to worship, pray, live, and love together regardless of ecclesiastical affiliation. 3. Anything that divides the true people of God and prevents their demonstration of essential unity before a hostile world is sin.

Watching The Crucifixion For The Pleasure Of It

While in Cleveland to promote the film “King of Kings,” Ron Randell recently took the opportunity to chatter to the press about the film’s critics. “It’s chic for critics to tear apart a religious movie,” he protested, “but they’re not students of the Scriptures.” Randell plays the role of the Centurion, a role not spelled out in the New Testament but created for the movie by Philip Yordan.

Since his role stems from the script of Yordan, his appeal to the Holy Scriptures loses considerable force. And it is equally “chic” to assume that all the film’s critics are strangers to the Scriptures.

Randell’s own canons of criticism? According to the Cleveland Press Randell declared, “The movie carries a Christian message, but it should not be judged for that but rather as entertainment and as a money-making enterprise.”

“King of Kings” has received the most unfavorable comment given a religious film in a long time. But Randell outdoes the critics when he urges that the film should be evaluated not in terms of whether it conveys the factual story of Christ, but whether or not it entertains and makes money. His defense is so damning as to make it doubtful whether the film will achieve either objective.

Communism’S Religious Slip Was Showing

G. K. Chesterton once made the shrewd observation that to swear effectively men must make reference to God. Imagine, he said, an atheistic evolutionist trying for a blood-curdling oath by swearing in the name of natural selection, or by the slimy, primeval amoeba.

Chesterton spotlighted the truth that all men so truly live and move and have their being in God that without him they cannot think, act, or even swear. Men curse and reject God only by appealing to him.

This need for reference to the ultimate which compels an appeal to God in order to deny him—this use of the religious to be irreligious—the Communists have demonstrated. They boast of their atheism and materialism; they loudly deny man’s immortality and God’s existence. Spiritual values and ethical standards are said to exist only in the minds of corrupt capitalists who use them to dope the poor into a docility that accepts pie in the sky. That these ideas have been used to exploit people, the Communists unfortunately can show. But that these ideas have no existence except in Western capitalistic minds, they have not demonstrated. On the contrary, in their “moments of truth” off-moments, to be sure, the Reds have demonstrated just the opposite.

A classic example of this fact is the way the Communists brought Stalin to dishonor. To destroy his image and the cult of his personality by little Albania and big Red China, Khrushchev and the 22nd Party Congress had to number Stalin among the sinners. They condemned him as a mass murderer and criminal abuser of countless honest Russian people, then proceeded to voice a kind of public repentance for the moral failures of the long-honored leader of the Soviet government.

Only by appealing to those moral standards whereby the Christian West has long known what the Communists just lately discovered, could the Party Congress justify its degrading removal of Stalin from a place of honor in the Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow’s great Red Square. This not only uses religion to exploit, it also demonstrates that even Communists must appeal to ethical standards of right and wrong to separate the sheep from the goats.

But there are further instances where the Communists have verified Chesterton. While in America, Khrushchev referred to both God and Jesus, and even quoted Scripture. Mikoyan on U.S. television proudly professed his atheism, but needing something greater than himself to lend force to his words, he appealed to the devil.

But only recently, in the fantastic speech made by Darya Lazurkina before the 22nd Party Congress, the latest, most bizarre appeal of atheistic communism to the supernatural occurred. Imprisoned by Stalin for almost 20 years, she survived by spiritualistic communications with Lenin, who recently informed her, she said, that he did not enjoy occupying the same bedroom with Stalin. Darya told the Congress, “I always had Lenin in my heart and asked him what to do. Yesterday I consulted Lenin again, and he seemed to stand before me as if alive, and said, ‘It is unpleasant for me to lie next to Stalin, who caused the party so much harm.’ ”

The West could well learn that although the specific character of evil is manifold, the overall pattern of Soviet behavior is predictable. By its own explicit avowal communism is intent on the destruction of the Christian tradition and the remaking of the world on Communist lines. If the West were more conscious of her Christian heritage she would recognize that the form of the Communist rebellion must necessarily be derived from the tradition they intend to destroy.