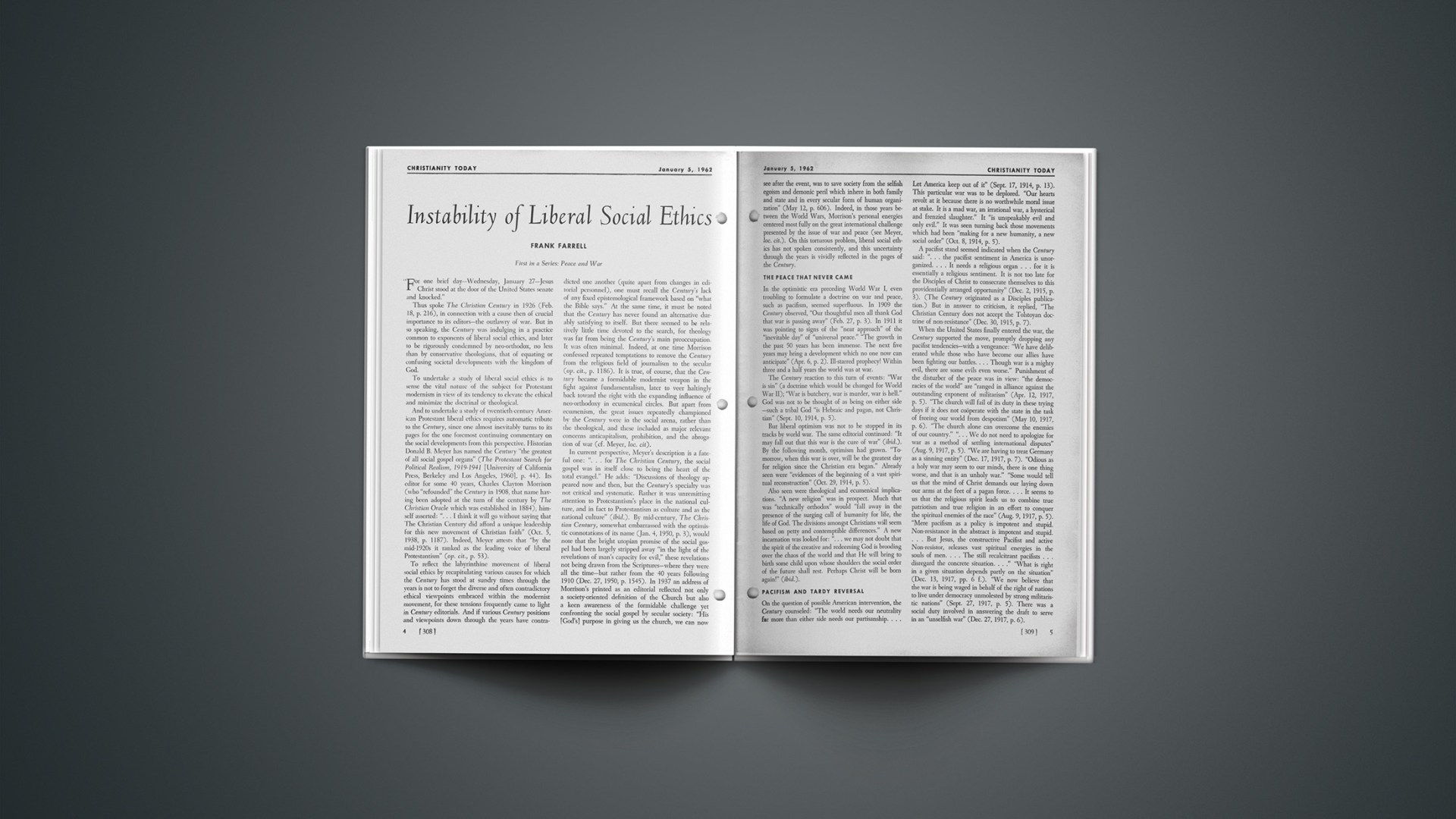

First in a Series: Peace and War

“For one brief day—Wednesday, January 27—Jesus Christ stood at the door of the United States senate and knocked.”

Thus spoke The Christian Century in 1926 (Feb. 18, p. 216), in connection with a cause then of crucial importance to its editors—the outlawry of war. But in so speaking, the Century was indulging in a practice common to exponents of liberal social ethics, and later to be rigorously condemned by neo-orthodox, no less than by conservative theologians, that of equating or confusing societal developments with the kingdom of God.

To undertake a study of liberal social ethics is to sense the vital nature of the subject for Protestant modernism in view of its tendency to elevate the ethical and minimize the doctrinal or theological.

And to undertake a study of twentieth-century American Protestant liberal ethics requires automatic tribute to the Century, since one almost inevitably turns to its pages for the one foremost continuing commentary on the social developments from this perspective. Historian Donald B. Meyer has named the Century “the greatest of all social gospel organs” (The Protestant Search for Political Realism, 1919–1941 [University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1960], p. 44). Its editor for some 40 years, Charles Clayton Morrison (who “refounded” the Century in 1908, that name having been adopted at the turn of the century by The Christian Oracle which was established in 1884), himself asserted: “… I think it will go without saying that The Christian Century did afford a unique leadership for this new movement of Christian faith” (Oct. 5, 1938, p. 1187). Indeed, Meyer attests that “by the mid-1920s it ranked as the leading voice of liberal Protestantism” (op. cit., p. 53).

To reflect the labyrinthine movement of liberal social ethics by recapitulating various causes for which the Century has stood at sundry times through the years is not to forget the diverse and often contradictory ethical viewpoints embraced within the modernist movement, for these tensions frequently came to light in Century editorials. And if various Century positions and viewpoints down through the years have contradicted one another (quite apart from changes in editorial personnel), one must recall the Century’s lack of any fixed epistemological framework based on “what the Bible says.” At the same time, it must be noted that the Century has never found an alternative durably satisfying to itself. But there seemed to be relatively little time devoted to the search, for theology was far from being the Century’s main preoccupation. It was often minimal. Indeed, at one time Morrison confessed repeated temptations to remove the Century from the religious field of journalism to the secular (op. cit., p. 1186). It is true, of course, that the Century became a formidable modernist weapon in the fight against fundamentalism, later to veer haltingly back toward the right with the expanding influence of neo-orthodoxy in ecumenical circles. But apart from ecumenism, the great issues repeatedly championed by the Century were in the social arena, rather than the theological, and these included as major relevant concerns anticapitalism, prohibition, and the abrogation of war (cf. Meyer, loc. cit).

In current perspective, Meyer’s description is a fateful one: “… for The Christian Century, the social gospel was in itself close to being the heart of the total evangel.” He adds: “Discussions of theology appeared now and then, but the Century’s specialty was not critical and systematic. Rather it was unremitting attention to Protestantism’s place in the national culture, and in fact to Protestantism as culture and as the national culture” (ibid.). By mid-century, The Christian Century, somewhat embarrassed with the optimistic connotations of its name (Jan. 4, 1950, p. 3), would note that the bright utopian promise of the social gospel had been largely stripped away “in the light of the revelations of man’s capacity for evil,” these revelations not being drawn from the Scriptures—where they were all the time—but rather from the 40 years following 1910 (Dec. 27, 1950, p. 1545). In 1937 an address of Morrison’s printed as an editorial reflected not only a society-oriented definition of the Church but also a keen awareness of the formidable challenge yet confronting the social gospel by secular society: “His [God’s] purpose in giving us the church, we can now see after the event, was to save society from the selfish egoism and demonic peril which inhere in both family and state and in every secular form of human organization” (May 12, p. 606). Indeed, in those years between the World Wars, Morrison’s personal energies centered most fully on the great international challenge presented by the issue of war and peace (see Meyer, loc. cit.). On this torturous problem, liberal social ethics has not spoken consistently, and this uncertainty through the years is vividly reflected in the pages of the Century.

The Peace That Never Came

In the optimistic era preceding World War I, even troubling to formulate a doctrine on war and peace, such as pacifism, seemed superfluous. In 1909 the Century observed, “Our thoughtful men all thank God that war is passing away” (Feb. 27, p. 3). In 1911 it was pointing to signs of the “near approach” of the “inevitable day” of “universal peace.” “The growth in the past 50 years has been immense. The next five years may bring a development which no one now can anticipate” (Apr. 6, p. 2). Ill-starred prophecy! Within three and a half years the world was at war.

The Century reaction to this turn of events: “War is sin” (a doctrine which would be changed for World War II); “War is butchery, war is murder, war is hell.” God was not to be thought of as being on either side—such a tribal God “is Hebraic and pagan, not Christian” (Sept. 10, 1914, p. 5).

But liberal optimism was not to be stopped in its tracks by world war. The same editorial continued: “It may fall out that this war is the cure of war” (ibid.). By the following month, optimism had grown. “Tomorrow, when this war is over, will be the greatest day for religion since the Christian era began.” Already seen were “evidences of the beginning of a vast spiritual reconstruction” (Oct. 29, 1914, p. 5).

Also seen were theological and ecumenical implications. “A new religion” was in prospect. Much that was “technically orthodox” would “fall away in the presence of the surging call of humanity for life, the life of God. The divisions amongst Christians will seem based on petty and contemptible differences.” A new incarnation was looked for: “… we may not doubt that the spirit of the creative and redeeming God is brooding over the chaos of the world and that He will bring to birth some child upon whose shoulders the social order of the future shall rest. Perhaps Christ will be born again!” (ibid.).

Pacifism And Tardy Reversal

On the question of possible American intervention, the Century counseled: “The world needs our neutrality far more than either side needs our partisanship.… Let America keep out of it” (Sept. 17, 1914, p. 13). This particular war was to be deplored. “Our hearts revolt at it because there is no worthwhile moral issue at stake. It is a mad war, an irrational war, a hysterical and frenzied slaughter.” It “is unspeakably evil and only evil.” It was seen turning back those movements which had been “making for a new humanity, a new social order” (Oct. 8, 1914, p. 5).

A pacifist stand seemed indicated when the Century said: “… the pacifist sentiment in America is unorganized.… It needs a religious organ … for it is essentially a religious sentiment. It is not too late for the Disciples of Christ to consecrate themselves to this providentially arranged opportunity” (Dec. 2, 1915, p. 3). (The Century originated as a Disciples publication.) But in answer to criticism, it replied, “The Christian Century does not accept the Tolstoyan doctrine of non-resistance” (Dec. 30, 1915, p. 7).

When the United States finally entered the war, the Century supported the move, promptly dropping any pacifist tendencies—with a vengeance: “We have deliberated while those who have become our allies have been fighting our battles.… Though war is a mighty evil, there are some evils even worse.” Punishment of the disturber of the peace was in view: “the democracies of the world” are “ranged in alliance against the outstanding exponent of militarism” (Apr. 12, 1917, p. 5). “The church will fail of its duty in these trying days if it does not coöperate with the state in the task of freeing our world from despotism” (May 10, 1917, p. 6). “The church alone can overcome the enemies of our country.” “… We do not need to apologize for war as a method of settling international disputes” (Aug. 9, 1917, p. 5). “We are having to treat Germany as a sinning entity” (Dec. 17, 1917, p. 7). “Odious as a holy war may seem to our minds, there is one thing worse, and that is an unholy war.” “Some would tell us that the mind of Christ demands our laying down our arms at the feet of a pagan force.… It seems to us that the religious spirit leads us to combine true patriotism and true religion in an effort to conquer the spiritual enemies of the race” (Aug. 9, 1917, p. 5). “Mere pacifism as a policy is impotent and stupid. Non-resistance in the abstract is impotent and stupid.… But Jesus, the constructive Pacifist and active Non-resistor, releases vast spiritual energies in the souls of men.… The still recalcitrant pacifists … disregard the concrete situation.…” “What is right in a given situation depends partly on the situation” (Dec. 13, 1917, pp. 6 f.). “We now believe that the war is being waged in behalf of the right of nations to live under democracy unmolested by strong militaristic nations” (Sept. 27, 1917, p. 5). There was a social duty involved in answering the draft to serve in an “unselfish war” (Dec. 27, 1917, p. 6).

Of course, oversimplification in the fervor of patriotic war effort was nothing new. But within a brief period the Century had embraced the “just war” theory in place of its earlier assessment of “mad war” and “frenzied slaughter.”

Cheering Government Regulation

Alongside this theory, emphasis was laid upon the “compensations of war”—“the social, economic and political benefits” (Nov. 1, 1917, p. 5). The wealth was being redistributed (ibid.); U. S. “pagan monopolists” were being curbed. “The peace which prevailed before this war was just as barbarous and unchristian as the war itself”: “The preventable industrial accidents, the ruthless slaughter of infants who died for lack of ice and milk, the exploitation of women …” (Sept. 6, 1917, p. 5). The inevitable wartime socialist drift was cheered on: “The principle of government interference in the domestic and industrial economies of the people was never carried so far or so systematically as now, and it is probable that the use of the principle for social well-being will be extended rather than restricted after the war” (Dec. 27, 1917, p. 7). “Never has … [the social] gospel been able to find men’s minds so filled with social things as it finds them now …” (Sept. 12, 1918, p. 8).

Post-War Crusade Against War

After such excesses of optimism, disillusion had to set in. Originally favoring a tough peace, the Century by late 1919 denounced the Treaty of Versailles terms as “punitive, vindictive, terrorizing. They look to the impossible end of permanently maiming Germany. They are not redemptive, and they are therefore not Christian” (Sept. 18, p. 6). By 1922 the Century was seriously questioning its wartime counsel. “… It is increasingly clear that war is a great and terrible wrong … that even its by-products, over which wartime orators talked so eloquently, are either illusory or vicious.… We are not quite sure that the great objectives were gained.” There was admission that the pacifists may have been right, and regret was expressed concerning one-sided criticism of Germany. Christ’s teachings, it was affirmed, had not been taken seriously. “… War is a crime.” “… We know that all the defenses we have made for ourselves as apologists for war are nothing worth. The cultivation of the war spirit was the definite and profitable business of a whole company of diplomatists, politicians, profiteers and militarists.…” Yet there was heart for some injudicious optimism: “The bravery and picturesqueness of military affairs have departed never to return.” Christian men could never again justify war or “count it a duty to go to war in any cause” (May 4, pp. 549 f.).

The old liberal optimism, having repented of its misplaced confidence in war, hovered for a time over Geneva. “The League of Nations idea is the extension to international relationships of the idea of the Kingdom of God as a world order of good will. From the Christian point of view it is hard to see how anyone can oppose it” (Sept. 25, 1919, p. 7). But the Century, in contrast to the overwhelming weight of U. S. Protestant opinion, did come to oppose the League—because of its power to apply sanctions (Jan. 28, 1926, pp. 104–106; cf. Robert Moats Miller, American Protestantism and Social Issues, 1919–1939 [The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1958], pp. 319–324). The Century saw “two plans of world organization,” the League and the outlawry of war (Apr. 9, 1925, p. 466). Its sympathies lay with the latter. “In the judgment of those who advocate an organization of the world on the basis of the outlawry of war, it was a sound instinct that kept the United States from joining the league of nations [sic].” “We will not undertake commitments that involve us in advance in Europe’s military controversies.… The American national morality is sound. Its idealism has suffered severe shock and strain. It trusted once in war to end war, but it will never be enticed into such moral folly again” (Mar. 19, 1925, p. 371).

Century editor Morrison would become one of the principal advocates of the outlawry of war movement in the United States. Early in 1924 the Century urged the churches to outlaw war without waiting upon the state, asked them to withdraw “spiritual sanction” from war (Jan. 31, pp. 134 f.).

At one point the Century favored entering the Permanent Court for International Justice (July 16, 1925, pp. 914 f.), but when the Court made no provision for outlawry of war, the Century spoke of its “worthlessness as an instrument of world peace” (Jan. 14, 1926, p. 40) and sharply criticized the Federal Council of Churches for “artificially” creating “passionate churchly interest” in U. S. adherence to the Court (Jan. 7, 1926, p. 9). The Century did not consider its stands on the League and World Court as isolationist, but rather as internationalist. Outlawry of war embodied the true internationalism. Idaho’s Senator William E. Borah fought U. S. participation in League and Court but led the outlawry forces in the Senate. The Century described him as “the most internationally-minded statesman in Washington,” representing “the most truly Christian internationalism” to be found in Congress (Jan. 7, 1926, p. 15). The Century’s internationalism spoke with an optimistic American accent: “With hands thus clean of any spoil and with motives unsuspected of selfish ambition, America is foreordained to leadership in world-embracing crusade to abolish war” (Dec. 11, 1924, p. 1590). The Century did turn from Borah to the extent of supporting U. S. adherence to the Court, though there would later be misgivings (Feb. 4, 1926, pp. 136 f.; Jan. 31, 1940, p. 136).

Banishing War On Paper

In 1928 the Century hailed as “the most important event in modem history” the U. S. offer to join with France in preparing a treaty for the renunciation of war to be presented to all the nations for universal adoption. “… The fact that America has defined the issue between peace and war in simple, unambiguous terms and has chosen peace, spells the doom of war. Its doom may be imminent, or it may be deferred for a generation, but it is inexorable.… If Christ were standing among us it would be like him to say, I see Satan falling as lightning from heaven!” (Jan. 19, 1928 p. 70).

Morrison had written a book on The Outlawry of War which was being extensively advertised in Century pages. And when on August 27, 1928, the Pact of Paris, also called the Kellogg-Briand Pact, was signed by the United States and 14 other nations, he exulted in Paris: “Today international war was banished from civilization” (italics his). He also warned: “The moral chaos that would ensue upon a major violation of this treaty would be worse than the devastation of war itself” (Sept. 6, 1928, p. 1070).

The U. S. Senate ratified the treaty on January 15, 1929, and the Century predicted: “… we can, perhaps within a generation, recreate the psychology of the world so that the age-old presupposition of war as inevitable and glorious shall disappear from men’s thoughts and the presupposition of peace shall be firmly established in its place …” (Jan. 24, p. 99).

The task now was to create “a patriotic conscience which will make sure that the stars and stripes shall never be dishonored by being carried to a battlefield again” (Mar. 28, 1929, p. 415). “Under the new law of the land, the pacifist is the patriot.… The militarist … is the seditious person” (Sept. 2, 1931, p. 1086). But the treaty even before its adoption had been interpreted as to permit defensive wars, and the U. S. Senate so understood it, though no formal reservations were attached. Eventually the treaty was approved by almost all the nations, though in some cases with important reservations.

During this period realist Reinhold Niebuhr, who was very skeptical about outlawry of war, had some pertinent things to say even in the pages of the Century about liberal optimism: “I would say that the Barthian theologians are very sensitive to the iniquities of the present social system and that in this critical attitude they are measurably superior to the liberal theologians who frequently indulge the illusion that the League of Nations, or the latest bank merger, or the last humanitarian campaign are proofs of the immanent realization of the new heaven and the new earth” (July 15, 1931, p. 924).

The Century charged ex-President Coolidge with cynicism when he asserted the need for an adequate army and navy to maintain peace (Apr. 11, 1929, p. 477). The September 2, 1931, issue gave assurances concerning the Kellogg Pact: “… the pact is young.… But it will grow—it will grow!” (p. 1086).

That very month Japan struck at Manchuria. By December the Century charged, in face of Japanese denial, that Japan had broken her pledge as signatory to the Kellogg Pact: “Japan has dishonored her pledge, broken international law, and thus branded herself as a criminal among the nations.” It was expected that if the League failed to solve the Manchuria crisis, the U. S. or another power would “call the powers into conference under the Kellogg pact.” “Mr. Hoover and Mr. Stimson can be counted on to see that the most solemn treaty ever signed by the nations shall not become a scrap of paper” (Dec. 2, pp. 1510 f.).

Here was unintended prophecy, for “a scrap of paper” was what the Pact was fast becoming. Historians have pointed out that a fundamental weakness of the Pact was that it provided no special machinery to enforce its provisions, but rather relied upon the machinery already established by the League. Secretary of State Frank Kellogg himself had declared that “the only enforcement behind the pact is the public opinion of the people.”

But the Century saw sanctions, or the use of force, as the weakness of the League, even while noting that for Wilson this was its heart (Dec. 23, 1931, p. 1617). In contrast, the journal called for “sanctions of peace” and the testing of their effectiveness. Japan should be charged before the World Court with violation of the Pact and recognition withheld from any attempt to annex Manchuria (Jan. 13, 1932, pp. 50 f.).

The League was castigated for hesitancy in rendering a verdict against Japan in face of Japan’s threat to withdraw from the League. In view of the Century’s later stand in favor of “universalizing” United Nations membership (see Aug. 4, 1954, p. 919), the earlier argument is particularly interesting: “Of course any withdrawal by Japan from the league would, ostensibly, weaken the importance of that organization. But if the league is to be kept outwardly imposing while inwardly it compounds with crime, its days as a servant of genuine international justice and good faith are numbered” (Jan. 18, 1933, p. 77). When the League did rule against Japan and Japan walked out, the Century verdict was: the League “saved its soul” and “its life” (Mar. 8, p. 321).

An editorial noting the fifth anniversary of the Kellogg Pact was titled, “Peace, Where There Is No Peace.” The “twin gods of capitalism and absolute national sovereignty” perhaps stood in the way (Aug. 23, 1933, p. 1055). In 1934 an editorial titled “Detach America from the Next World War!” pointed to the ineffectuality of covenants, pacts, and conferences due to lack of the necessary degree of “stability, responsibility and honor on the part of the various nations” (Mar. 28, p. 411). In 1935 the entire peace structure, including the Pact, was declared irrelevant and impotent. Britain had “disregarded” the Pact, Secretary of State Cordell Hull had “betrayed” it. Yet if there was any hope left for the peace system, it would have to be found in the Pact rather than the League, which was “vitiatedby the provision for the military enforcement of peace” (Sept. 11, pp. 1135 ff.).

It was a poignant hope. In point of fact, the Kellogg Pact had no observable deterrent effect upon the aggressions in Manchuria and later in China proper, nor upon Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, nor upon German-Italian intervention in Spain, nor on the other aggressions which at last culminated in World War II.

The liberal dream, its high confidence placed in the passage of a law, had drifted from the biblical doctrines of man and sin—and salvation as well. But it could not escape them. On these enduring realities, the dream shattered.