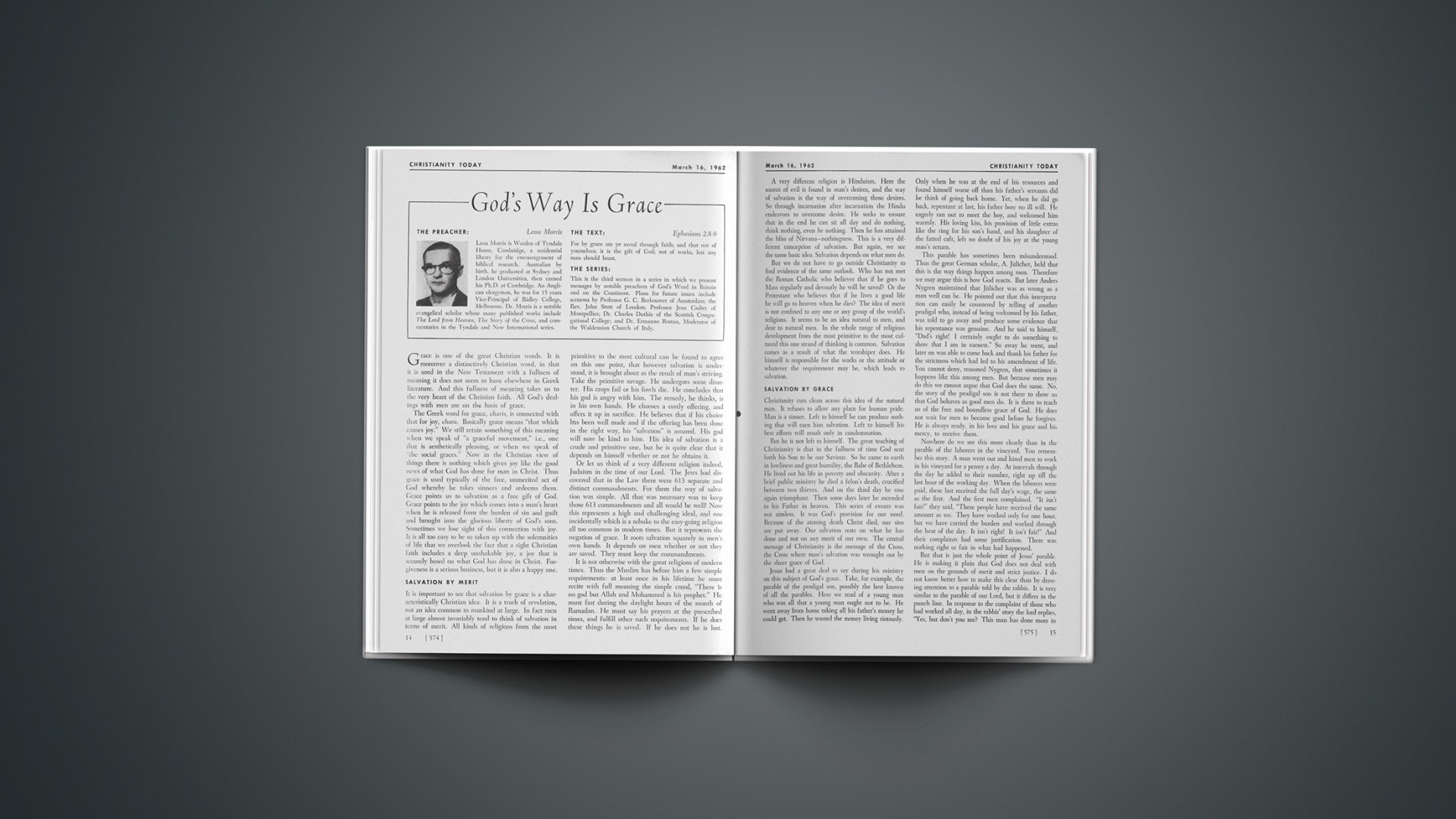

Leon Morris

The Preacher:

Leon Morris is Warden of Tyndale House, Cambridge, a residential library for the encouragement of biblical research. Australian by birth, he graduated at Sydney and London Universities, then earned his Ph.D. at Cambridge. An Anglican clergyman, he was for 15 years Vice-Principal of Ridley College, Melbourne. Dr. Morris is a notable evangelical scholar whose many published works include The Lord from Heaven, The Story of the Cross, and commentaries in the Tyndale and New International series.

The Text:

For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God; not of works, lest any man should boast.

The Series:

This is the third sermon in a series in which we present messages by notable preachers of God’s Word in Britain and on the Continent. Plans for future issues include sermons by Professor G. C. Berkouwer of Amsterdam; the Rev. John Stott of London; Professor Jean Cadier of Montpellier; Dr. Charles Duthie of the Scottish Congregational College; and Dr. Ermanno Rostan, Moderator of the Waldensian Church of Italy.

Grace is one of the great Christian words. It is moreover a distinctively Christian word, in that it is used in the New Testament with a fullness of meaning it does not seem to have elsewhere in Greek literature. And this fullness of meaning takes us to the very heart of the Christian faith. All God’s dealings with men are on the basis of grace.

The Greek word for grace, charis, is connected with that for joy, chara. Basically grace means “that which causes joy.” We still retain something of this meaning when we speak of “a graceful movement,” i.e., one that is aesthetically pleasing, or when we speak of “the social graces.” Now in the Christian view of things there is nothing which gives joy like the good news of what God has done for man in Christ. Thus grace is used typically of the free, unmerited act of God whereby he takes sinners and redeems them. Grace points us to salvation as a free gift of God. Grace points to the joy which comes into a man’s heart when he is released from the burden of sin and guilt and brought into the glorious liberty of God’s sons. Sometimes we lose sight of this connection with joy. It is all too easy to be so taken up with the solemnities of life that we overlook the fact that a right Christian faith includes a deep unshakable joy, a joy that is securely based on what God has done in Christ. Forgiveness is a serious business, but it is also a happy one.

Salvation By Merit

It is important to see that salvation by grace is a characteristically Christian idea. It is a truth of revelation, not an idea common to mankind at large. In fact men at large almost invariably tend to think of salvation in terms of merit. All kinds of religions from the most primitive to the most cultural can be found to agree on this one point, that however salvation is understood, it is brought about as the result of man’s striving. Take the primitive savage. He undergoes some disaster. His crops fail or his fowls die. He concludes that his god is angry with him. The remedy, he thinks, is in his own hands. He chooses a costly offering, and offers it up in sacrifice. He believes that if his choice has been well made and if the offering has been done in the right way, his “salvation” is assured. His god will now be kind to him. His idea of salvation is a crude and primitive one, but he is quite clear that it depends on himself whether or not he obtains it.

Or let us think of a very different religion indeed, Judaism in the time of our Lord. The Jews had discovered that in the Law there were 613 separate and distinct commandments. For them the way of salvation was simple. All that was necessary was to keep those 613 commandments and all would be well! Now this represents a high and challenging ideal, and one incidentally which is a rebuke to the easy-going religion all too common in modern times. But it represents the negation of grace. It roots salvation squarely in men’s own hands. It depends on men whether or not they are saved. They must keep the commandments.

It is not otherwise with the great religions of modern times. Thus the Muslim has before him a few simple requirements: at least once in his lifetime he must recite with full meaning the simple creed, “There is no god but Allah and Mohammed is his prophet.” He must fast during the daylight hours of the month of Ramadan. He must say his prayers at the prescribed times, and fulfill other such requirements. If he does these things he is saved. If he does not he is lost.

A very different religion is Hinduism. Here the source of evil is found in man’s desires, and the way of salvation is the way of overcoming those desires. So through incarnation after incarnation the Hindu endeavors to overcome desire. He seeks to ensure that in the end he can sit all day and do nothing, think nothing, even be nothing. Then he has attained the bliss of Nirvana—nothingness. This is a very different conception of salvation. But again, we see the same basic idea. Salvation depends on what men do.

But we do not have to go outside Christianity to find evidence of the same outlook. Who has not met the Roman Catholic who believes that if he goes to Mass regularly and devoutly he will be saved? Or the Protestant who believes that if he lives a good life he will go to heaven when he dies? The idea of merit is not confined to any one or any group of the world’s religions. It seems to be an idea natural to men, and dear to natural men. In the whole range of religious development from the most primitive to the most cultured this one strand of thinking is common. Salvation comes as a result of what the worshiper does. He himself is responsible for the works or the attitude or whatever the requirement may be, which leads to salvation.

Salvation By Grace

Christianity cuts clean across this idea of the natural man. It refuses to allow any place for human pride. Man is a sinner. Left to himself he can produce nothing that will earn him salvation. Left to himself his best efforts will result only in condemnation.

But he is not left to himself. The great teaching of Christianity is that in the fullness of time God sent forth his Son to be our Saviour. So he came to earth in lowliness and great humility, the Babe of Bethlehem. He lived out his life in poverty and obscurity. After a brief public ministry he died a felon’s death, crucified between two thieves. And on the third day he rose again triumphant. Then some days later he ascended to his Father in heaven. This series of events was not aimless. It was God’s provision for our need. Because of the atoning death Christ died, our sins are put away. Our salvation rests on what he has done and not on any merit of our own. The central message of Christianity is the message of the Cross, the Cross where man’s salvation was wrought out by the sheer grace of God.

Jesus had a great deal to say during his ministry on this subject of God’s grace. Take, for example, the parable of the prodigal son, possibly the best known of all the parables. Here we read of a young man who was all that a young man ought not to be. He went away from home taking all his father’s money he could get. Then he wasted the money living riotously. Only when he was at the end of his resources and found himself worse off than his father’s servants did he think of going back home. Yet, when he did go back, repentant at last, his father bore no ill will. He eagerly ran out to meet the boy, and welcomed him warmly. His loving kiss, his provision of little extras like the ring for his son’s hand, and his slaughter of the fatted caft, left no doubt of his joy at the young man’s return.

This parable has sometimes been misunderstood. Thus the great German scholar, A. Jülicher, held that this is the way things happen among men. Therefore we may argue this is how God reacts. But later Anders Nygren maintained that Jülicher was as wrong as a man well can be. He pointed out that this interpretation can easily be countered by telling of another prodigal who, instead of being welcomed by his father, was told to go away and produce some evidence that his repentance was genuine. And he said to himself, “Dad’s right! I certainly ought to do something to show that I am in earnest.” So away he went, and later on was able to come back and thank his father for the strictness which had led to his amendment of life. You cannot deny, reasoned Nygren, that sometimes it happens like this among men. But because men may do this we cannot argue that God does the same. No, the story of the prodigal son is not there to show us that God behaves as good men do. It is there to teach us of the free and boundless grace of God. He does not wait for men to become good before he forgives. He is always ready, in his love and his grace and his mercy, to receive them.

Nowhere do we see this more clearly than in the parable of the laborers in the vineyard. You remember this story. A man went out and hired men to work in his vineyard for a penny a day. At intervals through the day he added to their number, right up till the last hour of the working day. When the laborers were paid, these last received the full day’s wage, the same as the first. And the first men complained. “It isn’t fair!” they said, “These people have received the same amount as we. They have worked only for one hour, but we have carried the burden and worked through the heat of the day. It isn’t right! It isn’t fair!” And their complaints had some justification. There was nothing right or fair in what had happened.

But that is just the whole point of Jesus’ parable. He is making it plain that God does not deal with men on the grounds of merit and strict justice. I do not know better how to make this clear than by drawing attention to a parable told by the rabbis. It is very similar to the parable of our Lord, but it differs in the punch line. In response to the complaint of those who had worked all day, in the rabbis’ story the lord replies, “Yes, but don’t you see? This man has done more in one hour than you fellows have done working all day!” See how man’s incurable tendency to reason in terms of merit comes out in this parable. The man who received the full day’s pay for an hour’s work merited it. He deserved it. He had produced the full quota of work. But in Jesus’ parable the principle is that of grace. They received the wage not because they had earned it, but because their lord was good. In his mercy he chose to give them that which they had not merited. And so it is with salvation.

Salvation is all of grace. It is God’s good gift. It is not something cheap, for it was bought dearly. It was bought at the price of the blood of Christ, that “Lamb without blemish and without spot,” who was slain for us. But the price was paid by him and paid entirely. Nothing is left for us to pay. Nor is there room for works of righteousness that we may do. No good works can merit salvation. Salvation by way of grace excludes salvation by way of good works. This does not, of course, mean that good works are not important. They have their place, and a most important place, in the living out of our Christian faith. They are the necessary fruits of our salvation. But the point I am making is that they are not its root. They are its result and not its cause. The idea of grace, when properly understood, completely excludes such a thought.

So natural does it come to man to follow the way of merit rather than that of grace that even in the Christian Church there is a continual tendency to pervert the way of Christ. With the very best of intentions men sometimes put their emphasis in such a place that the essence of the Gospel as grace is obscured.

Thus there are those who insist on the necessity of proclaiming a social gospel, and who are so ceaseless in their endeavors to ensure that society is permeated by Christian principles that all that can be seen is social endeavor. Now I would not have it thought that the social implications of the Gospel are unimportant. They are very important. A right Christian faith will have respect to all aspects of living, and social relationships cannot but be affected accordingly. All that I am complaining about is the overstressing of the importance of these relationships to such an extent that the basic idea of good grace is obscured. It must be insisted upon that Christianity is first and foremost a religion of grace. Anything that obscures this is self-condemned.

It is possible to obscure the importance of grace in a very religious fashion. Thus some men do this in the way they regard the sacraments. The sacraments are, of course, very important. Our Lord himself commanded us to observe the sacraments and no true believer can accordingly regard them as anything other than highly important. But they are not the means of earning grace. Christ did not replace a system of law-keeping by a system of sacrament-keeping. He did not counsel his followers to regard the observance of sacraments as good works which being duly carried out would be suitably rewarded.

In fact, the sacraments, rightly understood, point us to God’s good grace. Baptism (among other things) symbolizes death to sin and a rebirth to righteousness. That is to say, it reminds us that left to ourselves we are at best unprofitable. We must die to all our sins and be born again in the power of God. And the Lord’s Supper is meaningless apart from the death of the Saviour. It is not his body, but his body broken for us, not his blood, but his blood poured out, that it sets forth. Both sacraments take their meaning from what Christ has done for us. They do not take their meaning from our efforts.

It is even possible to preach the Cross in a way which obscures God’s grace. I have sometimes heard men explain the meaning of the Cross in some such way as this: “Christ has done all this for you; therefore you should do such-and-such things for him. Christ has died for you: you must live for him.” Now I would not deny that it is legitimate to take the Cross as an incentive to godly living. I am sure that there is no greater incentive. What I am denying is that this is the major thrust of the Christian Gospel. We must allow nothing to obscure the great truth that salvation is all of grace. Our puny works may express some of the gratitude we feel for what he has done for us, but they cannot add to the perfection of his work.

If then we profess to be Christians it is well that we examine ourselves whether we are truly relying on God’s grace. Concern for human merit is so all-pervasive that it is easy for it to creep in. But to deny the primacy of grace is to deny the fundamental truth of Christianity. “By grace are ye saved.…”

The Shadow of the Cross

Then they hurried Christ, the Galilean,

Stumbling, bleeding, to Golgotha;

Home they drove the thirsty spikes,

And as the timber bottomed in the hole,

Blood spurted from the gaping wounds.

Still casts the Cross its shadow through the earth,

On camp and field and startled glen …

Still shines the Cross above our cluttered years,

In mystic symbol, bleeding heart.…

The Tree on which they hung the Galilean

Now lifts its head among the stars,

And branches still as redly in the sky.

W. E. BARD