A fortnightly report of developments in religion

In the shadow of Washington Cathedral in the nation’s capital on April 9–10, a small meeting took place which could possibly eventuate in a radical transformation of the face and character of American Protestantism, with repercussions, for good or ill, felt in theology, polity, preaching, missions, evangelism, education, and down the entire range of Protestant life and thought—ultimately to the nation itself.

Concluding Statement Of Delegation Chairmen

We have met as delegates of the Methodist Church, the Protestant Episcopal Church, the United Church of Christ and the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. to discuss the possibility of the formation of a church truly catholic, truly reformed, truly evangelical. Each communion has been represented by both clerical and lay members, all of whom are deeply involved in the life of their churches and many of whom are widely experienced in ecumenical relations. We are grateful to God for having led us into these conversations, and we believe on the basis of our preliminary discussions that the Holy Spirit is leading us to further explorations of the unity that we have in Jesus Christ and to our mutual obligation to give visible witness to this unity.

We have made no attempt to reach agreement in areas of difference. Rather, we have sought to isolate issues that need further study and clarification. Among these are: (1) the historical basis for the Christian ministry that is found in the Scriptures and the early church; (2) the origins, use and standing of creeds and confessional statements, (3) a restatement of the theology of liturgy; (4) the relation of word and sacraments.

All of the delegations had in mind that they represent churches having deep roots in the Reformation. At the meeting they were reminded by theological spokesmen of the “earnest concern” of the Reformation “for theological integrity and cultural relevance;” and that today these principles of “theological integrity and meaningful witness demand the union of the churches.”

The delegates earnestly beseech the members of their churches to be constant in prayer that the people of God may be open to Elis leading, that these communions may receive from Him new obedience and fresh courage, and that God’s will for his people may be made manifest before the world.

It was the unanimous decision to hold further consultations. The next meeting [is March 19–21, 1963].

Some 40 churchmen gathered for conversations concerning the possible merging of their four denominations with memberships totaling almost 19 million: The Methodist Church (10, 046, 293), the Protestant Episcopal Church (3,500,000), the United Presbyterian Church, U.S.A. (3, 259, 011), the United Church of Christ (2, 015, 037).

Billed as preliminary and exploratory, the sessions were closed to the press though interviews were granted. The atmosphere was reportedly amiable, the delegations including names like Eugene Carson Blake, James I. McCord, Theodore O. Wedel, Charles C. Parlin, Truman B. Douglass and John P. Dillenberger.

Further meetings will be held under the name of The Consultation on Church Union. Elected chairman for a two-year term was McCord, president of Princeton Theological Seminary.

The four-way merger plan was originally proposed by Blake, United Presbyterian Stated Clerk, in December, 1960.

Though combined membership of the four denominations involved in the talks does not total half the U.S. membership of the Roman Catholic Church, there are hopes of future additions. Delegates agreed to invite three more communions to join the consultations: the International Convention of Christian Churches (Disciples of Christ) with nearly two million members, the Evangelical United Brethren with 750,000, and the Polish National Catholic Church with about 300,000. The latter, organized in 1897 as a result of dissatisfaction with Roman Catholic administration and theology, has been in full communion with the Protestant Episcopal Church since 1956. The Evangelical United Brethren have been holding conversations with the Methodists, and the Disciples with the United Church of Christ.

While spokesmen told of enthusiasm in their respective communions for merger, they also noted opposition. The various hurdles ahead were many. Calvinist, Arminian and Catholic theologies are represented in the consulting churches, though many of the historic creedal positions have been watered down through the years. Dillenberger, in an address termed indicative of the atmosphere of the discussions, took note of a growing ecumenical theology in contrast to the diminishing publication of denominational theologies. He later asserted that union should be accomplished by “convergence” rather than by taking all things from all churches or by “trading tradition for tradition.” Convergence was described as a total rethinking of concepts in the light of concepts of other traditions.

Dillenberger, a member of the United Church of Christ, pointed toward what could become the most formidable hurdle of all—the apostolic succession of the episcopate taught by Episcopalians. He did not see church history arguing for an unbroken succession, though he acknowledged that the church of the future would very likely have bishops.

As if to point up anticipation of this vexatious ecumenical problem, the Episcopal delegation was larger than the other three, which were equal, and the other major address was delivered by Episcopalian Wedel, who argued for the historic episcopate.

How Congregationalists, who form the larger part of the United Church of Christ, will feel about having bishops remains to be seen. Also congregational in polity are the Disciples, who own a further doctrinal distinction—they practice believers’ baptism by immersion. But this could possibly form a bridge to the Baptists. Lutherans have been busy with mergers among themselves, but the ultimate hope of many churchmen across denominational lines is for a united Protestant church of America, all the while seeking to prevent schism within the various communions over this very issue. Blake told reporters that continuation and building of the current “mood” depends partly on dissemination of information to “educate the laity to the level of thought that rises above petty disagreements over minor points.”

The Second Call

It was less than two hours after the Washington Consultation on Church Union had been adjourned. Half a continent away, in a crowded Denver Hilton Hotel ballroom, a lone figure stepped to the rostrum. Some 1,200 persons sang lustily a stanza of the “Star-Spangled Banner”, recited pledges of allegiance to the U. S. and Christian flags, then bowed in the opening prayer of the 20th annual convention of the National Association of Evangelicals.

Some 48 hours and 25 press releases later, it was clear that the NAE had (l) renounced ecclesiastical isolation and (2) broken clean from right-wing extremism.

But resolutions chairman Arnold T. Olson, president of the Evangelical Free Church, cited what he termed an even more important action. He recalled that two decades ago leading U. S. evangelicals had issued a “call to St. Louis” for a meeting which ultimately gave rise to organization of NAE. It was time, Olson added, for “a second call,” whereupon he introduced a resolution asking NAE leaders “to issue a call to both constituent leaders and to leaders of other Bible believing groups not affiliated with the NAE, to meet together to discuss methods of strengthening evangelical witness and influences, and to find ways to initiate more comprehensive united action.”

Immediately preceding the “second call” was another resolution whereby NAE officially abandoned separatism:

“We believe that [spiritual] unity is manifested in love-inspired fellowship that stimulates cooperative effort toward a more effective Christian witness without the necessity of formal ecclesiastical union or uniformity of practice and polity. The NAE also looks with favor on group discussion and dialogue to assure the fair and accurate presentation of the evangelical position and in order to keep fully aware of developments in other areas of Christian life and work; faith and order. However, it should be noted that in participating in such discussions the NAE does not compromise the evangelical position of accepting the authority of the Scriptures nor does it identify itself with those who deny that authority.”

Still another precedent-shattering resolution declared that “communism is only one of many avenues through which Satan employs his powers of spiritual wickedness. We must therefore seek to maintain a proper balance.… The ‘Freedom Through Faith’ program should be continued and intensified.… The dangers of extreme positions are recognized and should be avoided.”

Two motions to temper the anti-extremism resolution were lost for lack of a second. The resolutions committee report was carried unanimously and without amendment.1Other resolutions voiced concern over certain aspects of the U. N., called for guarantees of religious freedom in “Alliance for Progress” contracts, and criticized trends toward secularism in education.

Has an ecumenical spirit rubbed off on NAE? Have New Delhi and the Blake-Pike proposal driven evangelicals to reassess their own posture toward fellow believers?

Geiger counters are plentiful in mining-conscious Denver, but one needed merely to tune his ear to key convention speakers to detect a measure of ecumenical fallout. The World and National Councils of Churches were properly assailed, but this time it was a qualified shellacking.

Said World Vision President Bob Pierce: “I’m not going to spend my time fighting communism. The danger without communism would be just as great. The problem is sin.”

“Don’t ask me to spend my life fighting the World Council of Churches,” he added. “If the World Council were to get together and subscribe to our beliefs,” Pierce declared, it would not eliminate the necessity of a revival.

Dr. Paul P. Petticord, past NAE president, told newsmen that “we are not opposed to the organic mergers of denominations. We would not oppose federated fellowships. But … we assume first that the Bible is the basis for our unity, and that through the Bible we find a relationship in Christ that establishes unity.”

Dr. Herbert S. Mekeel, also a former NAE president, cited “merger fever” as an element “we must reckon with.”

Mekeel, who declared that “New Delhi in order to be consistent must lead to Rome,” stressed as well that the NAE constituency should be considerate of the millions of believers whose churches are in the framework of the ecumenical movement.

For most of the delegates, the convention was a time of great fellowship, perhaps at the expense of other factors. The business session during which the resolutions were acted upon was attended by only about 10 per cent of an estimated 600 voting delegates who were in Denver.

Repeated pleas were made from the platform that delegates take time out to visit a special prayer room for intercession and meditation. Yet most of the time the room was empty except for an attendant.

A late Wednesday evening prayer meeting, however, saw some 75 per cent of the audience stay for the 10-minute session, which was followed by another special prayer meeting for ministers and missionaries. It lasted somewhat longer.

Evangelist Billy Graham told a banquet crowd that America may be on the verge of revival.

“All across the country,” he said, “I am finding unrelated prayer and Bible study groups, and I sense the same pattern of the Holy Spirit in this country that characterized the Wesleyan revival in England.”

“God is moving in places where we thought he could not move,” he added.

Other convention developments:

—Dr. Robert A. Cook, president of King’s College, was elected to a two-year term as NAE president. Dr. Jared F. Gerig was elected first vice-president and Dr. Rufus Jones second vice-president, both for one-year terms. Dr. C. C. Burnett was re-elected secretary and Carl A. Gundersen was re-elected treasurer.

—Gundersen was presented with the NAE’s “Layman of the Year” award for distinguished Christian service.

—The Marion (Indiana) Christian Church was named winner in an architectural competition sponsored jointly by NAE and Christian Life magazine.

—The NAE’s Commission on Chaplains disclosed that a thorough study was being prepared of the unified Sunday School curriculum now employed in the military services. Commission members were outspokenly critical of the curriculum system (see CHRISTIANITY TODAY, April 13, 1962).

—A theological study commission was reported to be working on what it termed “positive statements” defining evangelical conviction on the inspiration of the Bible, aspects of the person of Christ, and the nature of the Church.

Reformed Probing Action

Two major denominations of the Reformed tradition are proposing a joint resolution “to seek together a fuller expression of unity in faith and action.”

The Presbyterian Church in the United States with nearly 1,000,000 members, and the 250,000 member Reformed Church in America, made public a two-page statement at a news conference in the historic Church of the Pilgrims (Presbyterian) in Washington, D. C. this month.

A joint effort by the General Synod Executive Committee of the Reformed Church, and the Permanent Committee on Inter-Church Relations of the Presbyterian group, the resolution will be presented to the national general assemblies of each body.

While the stated clerk of each denomination made it clear that the resolution is not designed as a stepping stone to organic merger, neither shut the door to the ultimate possibility of such a merger.

The Rev. Norman E. Thomas, president of the General Synod of the Reformed Church called attention to the resolution’s avoidance of any specific reference to organic merger. “We hope it will lead to the opening of doors,” he said, “but we do not want to go beyond that now. There is real danger in becoming too serious too soon.”

The resolution included reference to a joint statement of cooperation made in 1874, speaking of “a union, not organic, but nevertheless a union real and practical.” Spokesmen stated that ultimate reunion of the Body of Christ should come as a result of cooperation, not to promote cooperation.

Joint exploration is suggested in the following areas of common concern:

Doctrine and Polity, Worship and Liturgy; World Missions and Ecumenical Relations;

Christian Education, including higher education;

Theological Education, including exchange of students and professors; A nationwide strategy for Evangelism and Church Extension and Retention;

Communicant referrals and mutual pastoral care, including chaplains and Armed Forces personnel;

Stewardship Education and Cultivation;

Interchange of Ministers and Church Workers, including consideration of pensions and annuities;

Men’s Work, Women’s Work, and Youth Work;

Christian Social Concern and Action;

Reciprocal studies of denominational administrative and organizational structure;

Exchange of pulpits, conference leaders, consultants and advisors;

Use of official church papers to acquaint our entire constituencies with the life and work of both churches, including church publications and communications media;

Developing personal acquaintance through exchange of sizeable groups of fraternal delegates to the General Synod, the General Assembly, Synods, Presbyteries and Classes, to Men’s, Women’s, and Youth assemblies and conferences.

The stated clerks of both denominations, declared that the committees which drafted the statement are widely representative of the dichotomy of thought within the whole of the churches.

If the national assemblies of both churches accept the resolution, each will appoint a committee of 12 to engage in joint exploration of these areas, and to make annual recommendations for further steps.

B.B.

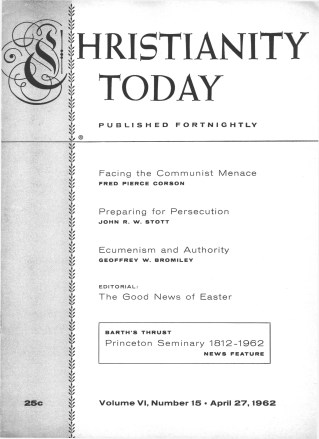

Princeton Seminary 1812–1962

Is a full-blown theological controversy about to break upon the North American scene?

The doctrinal whirlwind, some observers say, may already have been spawned. Professor John H. Hick of Princeton Theological Seminary, whose membership in the Presbytery of New Brunswick was denied by the Judicial Commission of the Synod of New Jersey because he would not affirm belief in the Virgin Birth, is expected to appeal his case before next month’s General Assembly of the United Presbyterian Church in the U. S. A.

A showdown is also possible among Southern Baptists at their annual sessions in San Francisco in June. An informal, eight-state delegation of pastors and laymen who met for two days in Oklahoma City last month were reported to have referred to “the current theological crisis within the denomination.” Their discussion centered on “infiltration of liberalism” in Southern Baptist seminaries, with particular attention to a recent book by Professor Ralph H. Elliott of Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, The Message of Genesis, published by the Southern Baptist press. Elliott’s view is that of the “documentary hypothesis” relative the authorship of the book of Genesis.

The case of the Princeton professor is particularly timely and noteworthy, for it involves one of America’s best-known seminaries which begins this week a 14-month sesquicentennial celebration.

Ask any fundamentalist-oriented layman to name a liberal seminary and he will likely respond, “Princeton.” Ask a theological liberal to cite the most fundamental of denominational seminaries and he is likewise apt to reply, “Princeton.”

Actually, both are right. Princeton has probably turned out more evangelical ministers than any other U. S. seminary. While the faculty avoids such controversy as would label it “fundamentalist” or “liberal,” the student body is not so prudent, and for the most part classifies itself as “fundy” or not. In recent years, incoming classes have been nearly one-half “fundy.” Among schools most strongly represented in last year’s student body was Wheaton College, which like the University of California and Maryville (Presbyterian) College had 14 of its graduates on the Princeton Seminary campus.

Other strongly evangelical schools represented in Princeton’s student body last year included Bob Jones University, Seattle Pacific College (Free Methodist), Nyack Missionary College (Christian and Missionary Alliance), Houghton College (Wesleyan Methodist), Olivet Nazarene College, and Taylor University.

Strangely enough, the only indexed reference to Princeton Seminary in Encyclopaedia Britannica is found under the subject heading “Fundamentalism.”

On the other hand, there seems little doubt that the theological movement of the Princeton faculty and administration has been consistently to the left in recent decades. One highly-informed source who was close to the Princeton leadership for many years puts it this way:

“I like the men there, and I think of some as still conservative. But I do not know of a recent appointment that has been of the conservative sort. The Princeton literature that comes to me makes me feel that the trend is not in that direction.”

The founding of Princeton Seminary can be traced back to an overture from the Presbytery of Philadelphia which came before the Presbyterian General Assembly in 1809. Two years later a plan was adopted by the assembly providing for establishment of a seminary designed “to form men for the Gospel ministry who shall truly believe, and cordially love, and therefore endeavour to propagate and defend, in its genuineness, simplicity, and fullness, that system of religious belief and practice which is set forth in the Confession of Faith, Catechisms, and Plan of Government and Discipline of the Presbyterian Church; and thus to perpetuate and extend the influence of true evangelical piety and Gospel order.”

The assembly made an agreement with the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton University) for use of campus space, and a cordial relationship has existed between the university and the seminary ever since. The campuses are still adjacent to each other, and there are many cooperative efforts between the two institutions, although they have always been operated independently.

The seminary opened on August 12, 1812, with three students and one professor, Dr. Archibald Alexander. Classes were initially held in his study. Five more students came in November of that year. Dr. Samuel Miller became the second professor in 1813. It was not until five years later that the first seminary building was erected, Alexander Hall, which still stands.

Charles Hodge, who was to become one of the greatest of American Protestant theologians, entered the seminary in 1816 after graduating from the college at Princeton. He stayed on as a faculty member and was said to have trained more men in theology (3, 000) than any other figure of his time. Hodge taught at the seminary for 50 years.

The seminary never had a president until 1903 when the office was assumed by Dr. Francis L. Patton, who served until 1912.

Hodge, two of his sons who also taught, Alexander, Miller, and Patton, plus Dr. Benjamin B. Warfield, who was professor of theology, all are recalled as evangelical giants. One seminary graduate has remarked that Warfield, who now looks impressively down from above the fireplace in the Campus Center, wears a disapproving expression.

If a single year could be referred to as a turning point for Princeton, it was probably 1913, when J. Ross Stevenson assumed the presidency. It was under Stevenson that the seminary experienced its greatest crisis, and the leading figure in the controversy which brought about the crisis was the late Dr. J. Gresham Machen, who was regarded by critics and admirers alike as the greatest leader of evangelical Christianity in his time. He was referred to as the one man the liberals had yet to answer.

Machen, a native of Baltimore, studied successively at Johns Hopkins University, Princeton Seminary, and at the Universities of Marburg and Göttingen in Germany. He joined the Princeton faculty in 1906 as an instructor and in 1914 was elected Assistant Professor of New Testament Literature and Exegesis. He was well known for his fundamentalist convictions and his stand increasingly became productive of difficulty. Seminary directors in 1926 elected Machen as professor of apologetics, but he never achieved the full-fledged professorship. The election set off a long chain of controversy climaxed in 1929 with a reorganization of the seminary by order of the General Assembly, which withheld Machen’s professorship.

The Gospel At Harvard

Evangelist Billy Graham preached regeneration to an overflow crowd of 2,500 at the Harvard Law Forum last month.

Following his talk, Graham and a long-time friend, Dr. Harold J. Ockenga of Park Street Church in Boston, took part in a panel with two Harvard Divinity School professors, entertaining questions from the audience.

A key point at issue was the relationship of evangelistic endeavor and social reform.

Graham stressed the need for personal commitment to Christ but also emphasized that evangelism and social responsibility were not mutually exclusive.

Ockenga agreed that there was no split between the two. “In fact,” he said, “we are pleading all the time for more social Gospel.”

“We have not abdicated this field,” Ockenga added.

The two Harvard panelists were Dr. James Luther Adams, Unitarian scholar, and Dr. Richard R. Niebuhr, associate professor of theology.

The meeting at Harvard climaxed a two-week campus crusade centered at three North Carolina colleges.

The election of Machen was made following the retirement of Dr. William Brenton Greene, who had served since 1892 in the chair first occupied by Patton. The chair, endowed by R. L. Stuart of New York, was first known as that of “the Relations of Philosophy and Science to the Christian Religion.” Dr. Clarence Edward Macartney was invited to assume the chair in 1925, but declined. Machen finally withdrew his name too, and directors named Cornelius Van Til first as instructor then as full professor. Van Til’s appointment likewise was never confirmed, and he taught only one year. In the summer of 1929, Machen led a faction which withdrew under protest from Princeton and formed Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. Van Til was among those who joined the faculty of the new school.

Current occupant of the Stuart chair, now referred to as that of Professor of Christian Philosophy, is Hick.

Stevenson served as president until 1936 and was succeeded by Dr. John H. Mackay, who started a controversy of his own by bringing from the Continent Dr. Emil Brunner to the Charles Hodge chair of systematic theology. Brunner’s neoorthodoxy drew fire from Presbyterians despite Mackay’s plea that the Continent was enjoying a “theological spring-time” in which he wished America to share. Brunner only stayed a year.

Mackay’s term reflected his passion for the missionary aspect of ecumenism. Says one recent Princeton graduate, who studied under Mackay as well as Dr. James I. McCord, who succeeded him:

“Whatever theological criticism must be made of Mackay’s administration, still he brought to the seminary a great and evangelical spirit.”

McCord is reportedly seeking to raise the academic prestige of the seminary to the level of Harvard, Yale, and Union. A major revision of the curriculum is already under way.

McCord’s most spectacular accomplishment thus far has been in lining up the eminent theologian Karl Barth to deliver a week of lectures. Barth, who was scheduled to lecture at the University of Chicago this week, is due in Princeton on Sunday. His appearance was to follow that of two prime movers of the ecumenical movement, Dr. W. A. Visser ’t Hooft, general secretary of the World Council of Churches, and Dr. D. T. Niles, general secretary of the East Asia Christian Conference. Niles and Visser ’t Hooft were to lecture this week along with Dr. James S. Stewart, professor of New Testament at New College, Edinburgh.

The town of Princeton, which embraces the campuses of the university as well as the seminary, is located in the heart of the Eastern seaboard population concentration, midway between New York and Philadelphia. It has managed nonetheless to retain a degree of quaint, small-town flavor. The shops along Nassau Street, which borders the campus, are old-fashioned but neat-appearing. The community boasts a religious distinction apart from the seminary location: Jonathan Edwards is buried there.

The 30-acre seminary campus consists of an administration building, two classroom buildings, a library, a chapel, a campus center, four dormitories, three apartment houses, a gymnasium and athletic field, two outdoor tennis courts, and an outdoor swimming pool, plus a complex of homes used by faculty members.

The seminary has a current enrollment of 445 students. Degrees offered include bachelor of divinity, master of religious education, master of theology, and doctor of theology.

Academic excellence and tradition continue to draw many evangelical intellectuals to Princeton. But the future of conservative theology depends on faculty appointments, which are being watched. Already influential conservative Presbyterians are weighing the need for a new denominational seminary, which some church leaders may prefer to the risk of a costly denominational split.

‘A Man For All Seasons’

“Gideon” and “A Man for All Seasons” are among the four stage plays2The other two: “The Caretaker” by Harold Pinter and “The Night of the Iguana” by Tennessee Williams. This year’s “Tony Awards” will be presented April 29 at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. nominated for this year’s major theater awards, which may indicate that religious themes are in for a big revival on Broadway.

“Gideon,” by Paddy Chayefsky, dramatizes the biblical character and his defeat of the Midianites (see CHRISTIANITY TODAY, March 2, 1962).

“A Man for All Seasons” is a historical drama which exalts the character of Sir Thomas More, famous sixteenth-century English lawyer and author of the classic Utopia who played a key role in the religiopolitical struggle during which the Church of England was established. The play was written in 1960 by Robert Bolt and played in London before opening in New York last fall.

More, as played by Paul Scofield, is subjected to a series of ethical entanglements and finally executed as the upshot of a frameup to which Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, is a party. The historical authenticity of some of the script is open to question, but the plot is highly relevant to the contemporary political situation in America. Facets of the plot appear to have been forerunners of such modern-day phenomena as five percenters, deep-freezes and vicuna, loyalty oaths, Fifth Amendment silence—and even the religious issue.

More may have been sympathetic with at least some aspects of the Reformation, but he remained loyal to the church of Rome and severely criticized those who withdrew. Upon learning of England’s break with Rome, the “man for all seasons” cries, “This isn’t reformation. This is war against the church.”

More was canonized in 1935. The title of the play is taken from a passage which was composed by Robert Whittington for Tudor schoolboys to put into Latin.

Arguing For Prayer

The U. S. Supreme Court heard arguments this month as to whether the daily recitation of a nonsectarian prayer in public schools is unconstitutional. A ruling, the first such in the nation’s history, was expected soon.

The arguments were heard by eight justices. Justice Charles E. Whittaker, who had retired from the bench just a few days before, was in the audience but will not enter the deliberations. Neither will Justice Byron White, who had not yet been confirmed when the arguments were heard. Should the justices split 4–4, the lower court decision will be upheld.

Petitioners, residents of the state of New York, are five parents: two Jewish, one Unitarian, one Society for Ethical Culture, and one nonbeliever. They initiated legal action to enjoin the saying of this prayer in the public schools of their district: “Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers, and our country.” Having been denied by the highest

New York state court, their petition was taken to the U. S. Supreme Court.

Opposing petitioners’ case are respondents (the Board of Education of the school district) and intervenors-respondents (16 families with children in the schools in question). Seven families are Protestant, five Roman Catholic, three Jewish, and one non-believing.

Before the justices took their seats the Crier proclaimed to the standing courtroom: “Oyez! Oyez! Oyez!… God save the United States and this Honorable Court!”

Next, seven attorneys were admitted to the bar. With uplifted hand they swore to “demean myself, as an attorney.… So help me God!”

Then for one hour attorney William J. Butler represented petitioners. After a few moments of presentation Justice Felix Frankfurter asked: “What is your petitioners’ exact grievance?” Butler replied that this prayer was a practice primarily violating the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment and secondarily the Free Exercise Clause of the same amendment.

Some minutes later Justice William J. Brennan, Jr., asked: “The whole premise of your argument is that this amounts to teaching?”

“Yes,” answered Butler, “the reason for this prayer is to inculcate in children a love of God.”

“Is that a bad thing?” immediately queried one justice.

Replied the attorney, “No.… we are also religious people … prayer is good … but we should not compound the civic with the religious.”

Bertram B. Daiker, respondents’ attorney, had 30 minutes. He argued that the Establishment Clause “was intended to prohibit a State religion but not to prevent the growth of a religious State.” Porter R. Chandler, intervenors-respondents’ attorney, took up the remaining half-hour of argument time. He stressed that the “Regents’ Prayer” is an embodiment of traditional civic prayer. When recited voluntarily, it represents “a reasonable and proper method of developing an appreciation and understanding of the basic principles of our national heritage.” Neither the First nor the Fourteenth Amendments were intended to abolish it.

Chandler saw petitioners’ objections analogous to the objection of some to the saying by their children of the Pledge of Allegiance (a practice which they consider idolatrous). Chandler noted that legislatures have responded by exempting the children of objecters, not by abolishing the Pledge itself.

Chandler went on to point out that to prevent children from saying this prayer impairs their constitutional rights to the “free exercise” of their beliefs—to open school with a public prayer.

Supporting the prayer were briefs amicus curiae of attorneys general of 18 states. They said such a prayer does not, in their opinion, violate their state constitutions.

Respondents’ brief quotes from the state constitutions or preambles thereto of 49 states acknowledging that the rights and liberties of the people issue from God and express gratefulness therefor. It also notes that “all Presidents without exception.… have publicly recognized the dependence of this nation on Almighty God.”

It is generally believed the decision will have far-reaching consequences if the Supreme Court declares the prayer unconstitutional. Such a ruling will not merely eliminate opening prayer in public schools from Maine to Hawaii, but also Bible reading, Christmas pageants, and every other semblance of religion.

Should U.S. Aid Schools In Colombia?

Forty million United States tax dollars are earmarked to help upgrade the “public” school system of that most Roman Catholic of Latin republics—Colombia.

Already sites have been chosen and architects named for some of the 22,000 classrooms to be built under the four-year program, to which Colombia will contribute half the cost.

Yet there seems to be no prospect of persuading Colombia to abrogate Vatican treaties under which the Roman church, as the state religion, has virtually complete power over “public” education.

Nor have there been any official U.S. appeals to bring about the reopening of any of the 200-plus Protestant schools closed as a result of clerical orders during the past few years—in a country said to be 50 per cent illiterate.

In some areas Protestant children have been refused enrollment in “public” schools. Everywhere Protestant students have been forced to join their Catholic classmates in taking three hours of Catholic instruction each week and attending Mass on Sundays and feast days. The instruction frequently ridicules Protestantism.

The new American-aided program also envisions building four normal schools, training 9,500 new teachers, giving in-service training to 11,000 instructors and developing several thousand supervisors and administrators.

In the past Protestants have found the doors of Colombian normal schools closed to them. It has been almost impossible for them to obtain teachers’ certificates. Catholic prelates have authority to pass on the hiring and firing of teachers and to prescribe or outlaw textbooks.

The anomalous sight of free America’s bolstering an arbitrary school system may be explained in part by the haste with which the agreement was formulated. Apparently it was rushed through within four months after the Alliance for Progress Treaty was signed so that President Kennedy could announce it with a muffled fanfare of drums during his December visit to Colombia.

The announcement, scarcely heard in the United States, was publicized widely by Colombian newspapers. But Protestant leaders in Colombia heard it and their insistent questions soon caused a flurry of activity in the American Embassy in Bogotá.

Ambassador Fulton Freeman and his United States Operations Mission (Point Four) aides belatedly sought to calm Protestant apprehensions. After conferences with Colombia’s President and with officials of the Ministry of Education, they reported these verbal assurances:

1. None of the American-financed schools will be built in the “mission territories” (the 19 sparsely-populated, rural areas, comprising three-fourths of the land area of Colombia, where Romanists have absolute control over all schools and Protestant schools are allowed only for non-Catholic foreigners).

2. Protestant children will not be denied access to the new schools, nor will they be forced to take the Catholic instruction that still will be required of Catholic students.

3. Protestants will have equal access to the new normal schools and no longer will be denied teachers’ certificates.

However, such assurances from temporary officials in the Ministry of Education have failed to quiet the fears of the Colombian Protestants. Dr. James E. Goff, Presbyterian educator who has documented the running story of the Colombian persecution, puts it this way:

“Promises by Ministry officials, no matter how sincerely given, are worthless when stacked against the Concordat and the Treaty on Missions” (the two Vatican pacts which give the Catholics control over Colombian education).

“The present Administration,” Goff continued, “led by liberal statesman Alberto Lleras Camargo, is not inclined to enforce the restrictive articles of the two treaties. A subsequent conservative administration may well be disposed to do so. In all events, the Roman Catholic hierarchy may appeal to the treaties, which supposedly carry the force of law.” (A conservative administration is slated to take office this year.)

Goff saw “cause for surprise” that the U.S.O.M. people should have neglected to write into the education agreement itself adequate protection for Protestants.

“It is surely no secret,” he said, “that during the past 14 years the Protestants of Colombia have suffered a notorious religious persecution which has resulted in the death of 116 Protestant Christians because of their religious faith, the destruction by fire or dynamite of 66 Protestant churches or chapels, and the closing of over 200 Protestant schools.”

A clear violation of the American principle of church-state separation is involved in this situation, in the opinion of Colombian Protestant leaders and a number of Americans who know the facts.

Some officials in Washington already are retorting that the United States has no right to force our ideas of church-state separation on a friendly foreign country that needs our aid. Others say it is desirable and possible to urge the Colombian government to eliminate such discrimination against Protestants but that this discrimination should not deter us from pressing our campaign against illiteracy under the Alliance for Progress umbrella.

Protestants who see a violation of American principles in the Colombian program can point to a statement made in Washington last March by a Latin American expert, Senator Hipolito Marcano of Puerto Rico. Answering a hypothetical question regarding the use of United States aid for educational purposes in Latin America, Marcano said:

“I think that inasmuch as this is taxpayers’ money and the taxpayers’ money is controlled by the fundamental law of the land, which is the Constitution …, that control should accompany taxpayers’ money in all uses given it by the Federal Government.… I don’t think that because our money goes to a foreign country, they can do with the money what we cannot do with our own money in our own country.”

Even if this Constitutional ground should be shaken, there are Protestants and others in America who feel that this Colombian school program is completely wrong.

“Why should free America subsidize the denial of freedom,” such people ask. And they press their point with such question as:

“If Colombia needs more schools, why does she not start by striking down the tyrannical 1953 treaty with the Vatican under which Protestant schools are outlawed in 75 per cent of her territory?

“Why should America pour $40,000,000 into a school system that is dominated by prelates who have forced the closing of more than 200 Protestant schools while the Roman church and the Colombian government combined are unable to furnish schools for half the children of Colombia?”

The Rev. Lorentz D. Emery, another Protestant educator in Colombia, believes that American insistence on the inclusion of our principles of freedom in the Colombian education program would weaken clerical control of Colombian education, thereby “advancing education more than by the building of 22,000 classrooms.”

The American funds must be approved by Congress on a year-to-year basis.

The Overlappers

The three “trade associations” of the religious periodical press are the Associated Church Press, the Evangelical Press Association, and the Catholic Press Association. For some years, their memberships were for the most part mutually exclusive. The Evangelical and Catholic associations have well-defined membership qualifications resting on a theological base. The ACP has never had a membership credo, but its general orientation was that of Protestant liberalism. By this month it was obvious that much overlapping between ACP and EPA had developed and talks on cooperation were already under way.

The overlapping has developed as increasing numbers of publications originally aligned with EPA have also taken out ACP memberships.

ACP now has 163 member publications with an aggregate circulation of more than 17,000,000. EPA has 175 member publications with an aggregate circulation of more than 7, 600,000.

At its convention in New York this month, ACP presented 13 “Awards of Merit” and 16 honorable mentions.

The winners of merit awards:

Articles—CHRISTIANITY TODAY; The Churchman; Youth.

Editorials—The Churchman; Missions, Christianity and Crisis.

Denominational program or organized activity—Presbyterian Life; World Call; Missions Magazine.

News treatment (magazines)—Presbyterian Life; The Living Church; Baptist World.

News treatment (newspapers)—The Hawkeye Methodist.

Cited for honorable mention:

Articles—Unitarian Register and Universalist Leader; Saints Herald; Presbyterian Life.

Editorials—CHRISTIANITY TODAY, The Lutheran; Gospel Messenger; The Living Church.

Denominational program or organized activity—Baptist Record; Methodist Layman; Free Methodist.

News treatment (magazines)—CHRISTIANITY TODAY; The Christian; The Lutheran Standard; The Churchman.

News treatment (newspapers)—The Baptist Record; The Record.3Among periodicals which are members of ACP as well as EPA: Arkansas Baptist, Baptist Beacon, Baptist Program, The Baptist Record, Canadian War Cry, Christian Endeavor World, Christianity Today, Church Herald, The Commission, The Covenant Companion, Decision, Eternity, The Free Methodist, The Standard, United Evangelical Action, The War Cry, World Vision Magazine, Youth Compass, Youth in Action.

Barth’S Successor

Dr. Heinrich Ott, 33, of Riehen, Switzerland, will succeed Dr. Karl Barth as professor of systematic theology at the University of Basel.

Ott was once a student at Basel and studied under Barth. He became an instructor at the university after serving two Swiss parishes as minister.

Author of several books on contemporary theology, Ott declined an offer to teach at the University of Vienna to accept the Basel professorship.

No Hard Feelings

Cleared of all charges of immorality brought against him—charges that caused him to be deposed as Primate of the Orthodox Church of Greece—Archbishop Iakovos declared in Athens that he held “no hard feelings” for those who had accused him.

The ailing 67-year-old prelate, who abdicated in January “for the good of the Church” after only 12 days in the post of primate, said he had forgiven those who had charged him with “unmentionable acts.”

He declared he thought only in “loving” terms of those who “love me and (those who) hated me.”

People: Words And Events

Deaths:Dr. Evan Allard Reiff, 54, who had resigned January 25 as president of Hardin-Simmons University; in Abilene, Texas … Dr. Paul Rafaj, 66, president of the Synod of Evangelical Lutheran Churches; in Olyphant, Pennsylvania … Dr. Robert F. Cooper, 81, chairman of the department of ancient languages at Belhaven College; in Jackson, Mississippi … the Rt. Rev. Christopher Maude Chevasse, 77, former Anglican Bishop of Rochester; at Oxford, England … Dr. Walter J. Noble, 83, former president of the Methodist Church in Britain … Dr. Jan Szeruda, 71, former Bishop of the Polish Evangelical Augsburg (Lutheran) Church; in Warsaw … Miss Florence Sleidel, 65, Assemblies of God missionary who founded one of the world’s largest leper colonies, the New Hope Leprosarium in Liberia.

Resignation: As professor of preaching at Gordon College and Divinity School, Dr. Lloyd Perry, who will assume the pastorate of the Central Baptist Church of Indianapolis.

Retirement: As president of the World’s Christian Endeavor Union, Dr. Daniel A. Poling … as president of Augustana College, Dr. Conrad Bergendoff … as professor of preaching and applied Christianity at Boston University, Dr. Allan Knight Chalmers … as pastor of Central Baptist Church, Miami, Dr. C. Roy Angell.

Elections: As bishop of the Pacific Area of the Latin America Central Conference (Methodist), the Rev. Pedro Zottele of Chile … as president of the American Tract Society, G. Raymond Christensen.

Appointments: As professor of systematic theology at the Oberlin College Graduate School of Theology, Dr. J. Robert Nelson … as faculty members in systematic theology at Union Theological Seminary, New York, Dr. John Macquarrie and Dr. Paul L. Lehmann … as director of the Department of Education of the United Presbyterian Board of National Missions, Dr. Harry L. Stearns.… as religious editor for Protestant books with Doubleday and Company, Alex Liepa.

The highest canonical court in the church was unanimous in acquitting him of a charge of unbecoming conduct.

Convening as a court, the Holy Synod, the church’s executive body, ruled that the evidence brought against him did not substantiate the charges. Announcement came after five hours of deliberation. It said it “found unanimously that the accusations were not confirmed by the evidence produced … before the court.”

So ended a controversy which raged to a point where it threatened the nation’s unity, according to Religious News Service. Throughout his ordeal, press and churchmen alike called on the prelate to resign for the good of the church. The Greek government, for the first time in recent history, threatened to intervene in the church’s affairs and oust the archbishop. The prelate held out for a time but when government intervention seemed imminent he abdicated.

He was succeeded by Metropolitan Chrysostom Hadjistavrou of Philippi and Kavala, 83 years old and the oldest in point of service among all the Orthodox bishops in the world.