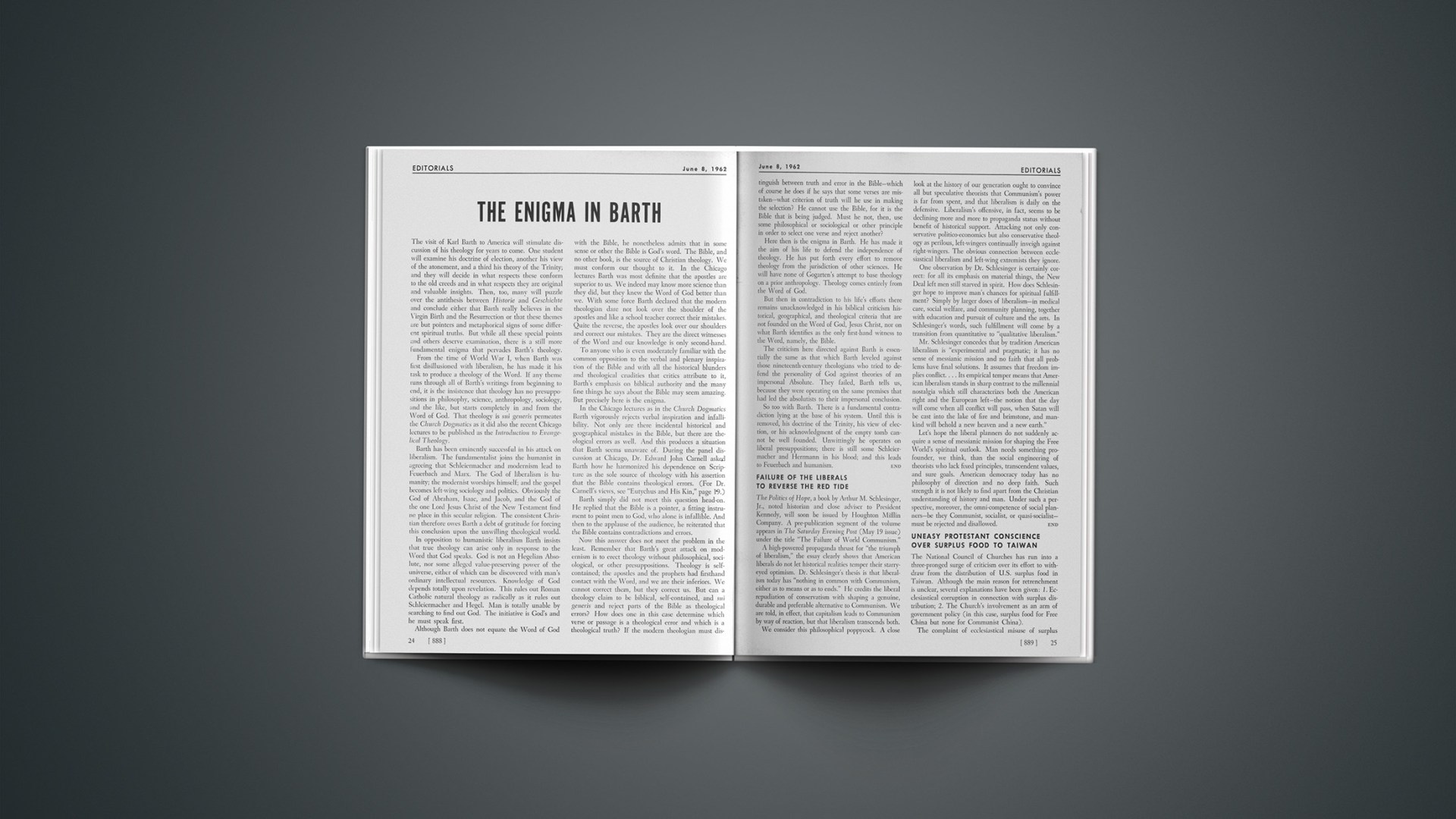

The visit of Karl Barth to America will stimulate discussion of his theology for years to come. One student will examine his doctrine of election, another his view of the atonement, and a third his theory of the Trinity; and they will decide in what respects these conform to the old creeds and in what respects they are original and valuable insights. Then, too, many will puzzle over the antithesis between Historie and Geschichte and conclude either that Barth really believes in the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection or that these themes are but pointers and metaphorical signs of some different spiritual truths. But while all these special points and others deserve examination, there is a still more fundamental enigma that pervades Barth’s theology.

From the time of World War I, when Barth was first disillusioned with liberalism, he has made it his task to produce a theology of the Word. If any theme runs through all of Barth’s writings from beginning to end, it is the insistence that theology has no presuppositions in philosophy, science, anthropology, sociology, and the like, but starts completely in and from the Word of God. That theology is sui generis permeates the Church Dogmatics as it did also the recent Chicago lectures to be published as the Introduction to Evangelical Theology.

Barth has been eminently successful in his attack on liberalism. The fundamentalist joins the humanist in agreeing that Schleiermacher and modernism lead to Feuerbach and Marx. The God of liberalism is humanity; the modernist worships himself; and the gospel becomes left-wing sociology and politics. Obviously the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the God of the one Lord Jesus Christ of the New Testament find no place in this secular religion. The consistent Christian therefore owes Barth a debt of gratitude for forcing this conclusion upon the unwilling theological world.

In opposition to humanistic liberalism Barth insists that true theology can arise only in response to the Word that God speaks. God is not an Hegelian Absolute, nor some alleged value-preserving power of the universe, either of which can be discovered with man’s ordinary intellectual resources. Knowledge of God depends totally upon revelation. This rules out Roman Catholic natural theology as radically as it rules out Schleiermacher and Hegel. Man is totally unable by searching to find out God. The initiative is God’s and he must speak first.

Although Barth does not equate the Word of God with the Bible, he nonetheless admits that in some sense or other the Bible is God’s word. The Bible, and no other book, is the source of Christian theology. We must conform our thought to it. In the Chicago lectures Barth was most definite that the apostles are superior to us. We indeed may know more science than they did, but they knew the Word of God better than we. With some force Barth declared that the modern theologian dare not look over the shoulder of the apostles and like a school teacher correct their mistakes. Quite the reverse, the apostles look over our shoulders and correct our mistakes. They are the direct witnesses of the Word and our knowledge is only second-hand.

To anyone who is even moderately familiar with the common opposition to the verbal and plenary inspiration of the Bible and with all the historical blunders and theological crudities that critics attribute to it, Barth’s emphasis on biblical authority and the many fine things he says about the Bible may seem amazing. But precisely here is the enigma.

In the Chicago lectures as in the Church Dogmatics Barth vigorously rejects verbal inspiration and infallibility. Not only are there incidental historical and geographical mistakes in the Bible, but there are theological errors as well. And this produces a situation that Barth seems unaware of. During the panel discussion at Chicago, Dr. Edward John Carnell asked Barth how he harmonized his dependence on Scripture as the sole source of theology with his assertion that the Bible contains theological errors. (For Dr. Carnell’s views, see “Eutychus and His Kin,” page 19.)

Barth simply did not meet this question head-on. He replied that the Bible is a pointer, a fitting instrument to point men to God, who alone is infallible. And then to the applause of the audience, he reiterated that the Bible contains contradictions and errors.

Now this answer does not meet the problem in the least. Remember that Barth’s great attack on modernism is to erect theology without philosophical, sociological, or other presuppositions. Theology is self-contained; the apostles and the prophets had firsthand contact with the Word, and we are their inferiors. We cannot correct them, but they correct us. But can a theology claim to be biblical, self-contained, and sui generis and reject parts of the Bible as theological errors? How does one in this case determine which verse or passage is a theological error and which is a theological truth? If the modern theologian must distinguish between truth and error in the Bible—which of course he does if he says that some verses are mistaken—what criterion of truth will he use in making the selection? He cannot use the Bible, for it is the Bible that is being judged. Must he not, then, use some philosophical or sociological or other principle in order to select one verse and reject another?

Here then is the enigma in Barth. He has made it the aim of his life to defend the independence of theology. He has put forth every effort to remove theology from the jurisdiction of other sciences. He will have none of Gogarten’s attempt to base theology on a prior anthropology. Theology comes entirely from the Word of God.

But then in contradiction to his life’s efforts there remains unacknowledged in his biblical criticism historical, geographical, and theological criteria that are not founded on the Word of God, Jesus Christ, nor on what Barth identifies as the only first-hand witness to the Word, namely, the Bible.

The criticism here directed against Barth is essentially the same as that which Barth leveled against those nineteenth-century theologians who tried to defend the personality of God against theories of an impersonal Absolute. They failed, Barth tells us, because they were operating on the same premises that had led the absolutists to their impersonal conclusion.

So too with Barth. There is a fundamental contradiction lying at the base of his system. Until this is removed, his doctrine of the Trinity, his view of election, or his acknowledgment of the empty tomb cannot be well founded. Unwittingly he operates on liberal presuppositions; there is still some Schleiermacher and Herrmann in his blood; and this leads to Feuerbach and humanism.

Failure Of The Liberals To Reverse The Red Tide

The Politics of Hope, a book by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., noted historian and close adviser to President Kennedy, will soon be issued by Houghton Mifflin Company. A pre-publication segment of the volume appears in The Saturday Evening Post (May 19 issue) under the title “The Failure of World Communism.”

A high-powered propaganda thrust for “the triumph of liberalism,” the essay clearly shows that American liberals do not let historical realities temper their starryeyed optimism. Dr. Schlesinger’s thesis is that liberalism today has “nothing in common with Communism, either as to means or as to ends.” He credits the liberal repudiation of conservatism with shaping a genuine, durable and preferable alternative to Communism. We are told, in effect, that capitalism leads to Communism by way of reaction, but that liberalism transcends both.

We consider this philosophical poppycock. A close look at the history of our generation ought to convince all but speculative theorists that Communism’s power is far from spent, and that liberalism is daily on the defensive. Liberalism’s offensive, in fact, seems to be declining more and more to propaganda status without benefit of historical support. Attacking not only conservative politico-economics but also conservative theology as perilous, left-wingers continually inveigh against right-wingers. The obvious connection between ecclesiastical liberalism and left-wing extremists they ignore.

One observation by Dr. Schlesinger is certainly correct: for all its emphasis on material things, the New Deal left men still starved in spirit. How does Schlesinger hope to improve man’s chances for spiritual fulfillment? Simply by larger doses of liberalism—in medical care, social welfare, and community planning, together with education and pursuit of culture and the arts. In Schlesinger’s words, such fulfillment will come by a transition from quantitative to “qualitative liberalism.”

Mr. Schlesinger concedes that by tradition American liberalism is “experimental and pragmatic; it has no sense of messianic mission and no faith that all problems have final solutions. It assumes that freedom implies conflict.… Its empirical temper means that American liberalism stands in sharp contrast to the millennial nostalgia which still characterizes both the American right and the European left—the notion that the day will come when all conflict will pass, when Satan will be cast into the lake of fire and brimstone, and mankind will behold a new heaven and a new earth.”

Let’s hope the liberal planners do not suddenly acquire a sense of messianic mission for shaping the Free World’s spiritual outlook. Man needs something profounder, we think, than the social engineering of theorists who lack fixed principles, transcendent values, and sure goals. American democracy today has no philosophy of direction and no deep faith. Such strength it is not likely to find apart from the Christian understanding of history and man. Under such a perspective, moreover, the omni-competence of social planners—be they Communist, socialist, or quasi-socialist—must be rejected and disallowed.

Uneasy Protestant Conscience Over Surplus Food To Taiwan

The National Council of Churches has run into a three-pronged surge of criticism over its effort to withdraw from the distribution of U.S. surplus food in Taiwan. Although the main reason for retrenchment is unclear, several explanations have been given: 1. Ecclesiastical corruption in connection with surplus distribution; 2. The Church’s involvement as an arm of government policy (in this case, surplus food for Free China but none for Communist China).

The complaint of ecclesiastical misuse of surplus food in Taiwan is of long standing. Roman Catholics have distributed U.S. food on the condition of attendance at Mass, in some cases punching tickets at church services to establish eligibility, and in others, selling food tickets for money to build churches. Under such procedures Catholic church attendance has multiplied remarkably. In some instances a black market in surplus foods involving government personnel has also been reported. While Protestant agencies are not wholly free of some abuses themselves, they have deplored violations and have sought to correct them. Their protest to Washington against the widespread Romanist infractions have met with no success. ICA officials in charge, many of them Roman Catholic, declared the complaints founded. If Protestants are having difficulty, said Catholic churchmen, they should withdraw from the field and leave it to Roman Catholics, who can manage their own affairs efficiently and effectively. Meanwhile the scandal of ecclesiastical misuse of U.S. surplus foods has continued. Roman Catholic spokesmen recently confused the issue by pleading for surplus food to Hong Kong refugees from Red China, thus putting the Roman Church “on the side of the starving refugee.” We are told that the situation in Hong Kong is presently under control, however, and that such special appeals smack of propaganda.

But there is another angle to the NCC withdrawal from Taiwan. Many U.S. ecclesiastical leaders, and among them, NCC leaders who urged Red China’s inclusion in the United Nations, want surplus food sent to Red China. Frequently one hears the defensive sentiment, “Our Lord said, if your enemy hungers, feed him.” Actually, if the withdrawal from Taiwan is really motivated by a Protestant desire to detach the Church from government policy, then ecclesiastical leaders should surely cancel religious distribution of U.S. government food everywhere. What’s more, American Protestantism has ventured into partnership with government in many places much closer to home, and could quite appropriately show some measure of uneasy conscience right there. Meanwhile, some Roman Catholic spokesmen want the U. S. government to supply food for relief purposes abroad irrespective of the availability of surplus supplies.

If the ecclesiastical movements were to disentangle themselves from government involvement, will they then minister to the hungry on the basis of Christian compassion and witness? If so, will they concern themselves first of all, or only, with the famine victims in Red China (and who will pay for this)? Or will they know equal or greater concern for the victims of Communist oppression who in fleeing the heel of the oppressor have left families and property behind?

The picture in Taiwan is confused. To withdraw from Taiwan religious distributions of government surplus can be justified, too, (if churchmen stop speaking of Red China in the same breath) on grounds other than ecclesiastical misuse. That U.S. surplus food is an embarrassment to the politicians is no secret. They are glad to move such supplies from storage, and for distribution on a person-to-person level they consider churches generally efficient and reliable agencies. But have the churches any right to credit themselves with a ministry of compassion to the hungry when they simply act as distribution agents for government supplied and government-transported food? And if it completely withholds its witness to Christ, has the Church any real commission to engage in humanitarianism devoid of all spiritual message? And is even humanitarianism simply distributing what the government pays for?

Billie Sol Estes’ Crimes Symptom Of A Deeper Disease

For three decades America has been infected with a disease. The Billie Sol Estes case is an evil symptom of a political philosophy of fiscal irresponsibility which leads to numerous abuses. In vigorously prosecuting the Estes case the American people should also look at the contributory factors. Whether we are prepared to submit to such examination and to undergo radical surgery in our economic life is the real question.

There is an occasional reference to the continuing outflow of gold from America, but political leaders seem unwilling to take the heroic action needed to deal with the crisis. This draining off of gold reserves is as much a menace to the nation as an uncontrolled hemorrhage to a bleeding patient.

Agriculture policy in the United States is a pyramiding example of political timidity on the one hand and the ineptness of “experts” in reaching a solution compatible with sound economics on the other. Cupidity, avarice and dishonesty, all apparently symbolized by Estes, should warn us as a nation that we too stand to be judged of God. Attempts to buy the votes of any bloc quickly breeds the desire for further government favors.

Estes, the symptom, needs to be dealt with, as well as Estes the man. But let us be sure we also deal with the disease.

A Father’S Day Suggestion About Helping The Fatherless

For many youngsters Father’s Day is just another day—they have no father to honor on this special occasion. As of January 1, 1960, an estimated 2,115,000 fatherless children under 18 dotted the United States and its possessions (Social Security Bulletin, Sept. 1960).

Although without an earthly living father, each of these children may take comfort in knowing the personal concern of the heavenly Father. Their creator, a compassionate God, is a “father of the fatherless” (Ps. 68:5) and a “helper of the fatherless” (Ps. 10:14).

But God does not therefore discount proper earthly care. He is solicitous for children’s well-being. He tells us through the Apostle James that “to visit the fatherless” is “pure religion and undefiled” (1:27).

In this area of service the secular world often puts the Church of Jesus Christ to shame. While the Church is busy with other programs, fraternal and civic groups, and government agencies as well, are assuming ever larger father roles toward youth. In one national nonchurch organization, for example, the men work exclusively at volunteering their help as “fathers” to fatherless boys in their communities. While such work is commendable, nevertheless in many instances the boys receive every kind of assistance—vocational, social, recreational, and financial—except the spiritual. It is highly pertinent to ask therefore: what profit it the fatherless if they gain earthly fatherly benevolences but are never introduced to their Father in heaven?

Around us are some of the more than two million fatherless. Through continuing personal interest, through foster home care and adoption, earthly fathers may actively implement the love and concern of God the heavenly Father. Perhaps this Father’s Day is a good time for those fathers who know the Saviour and know the blessings of a complete family relationship to consider enlarging their circle of love.