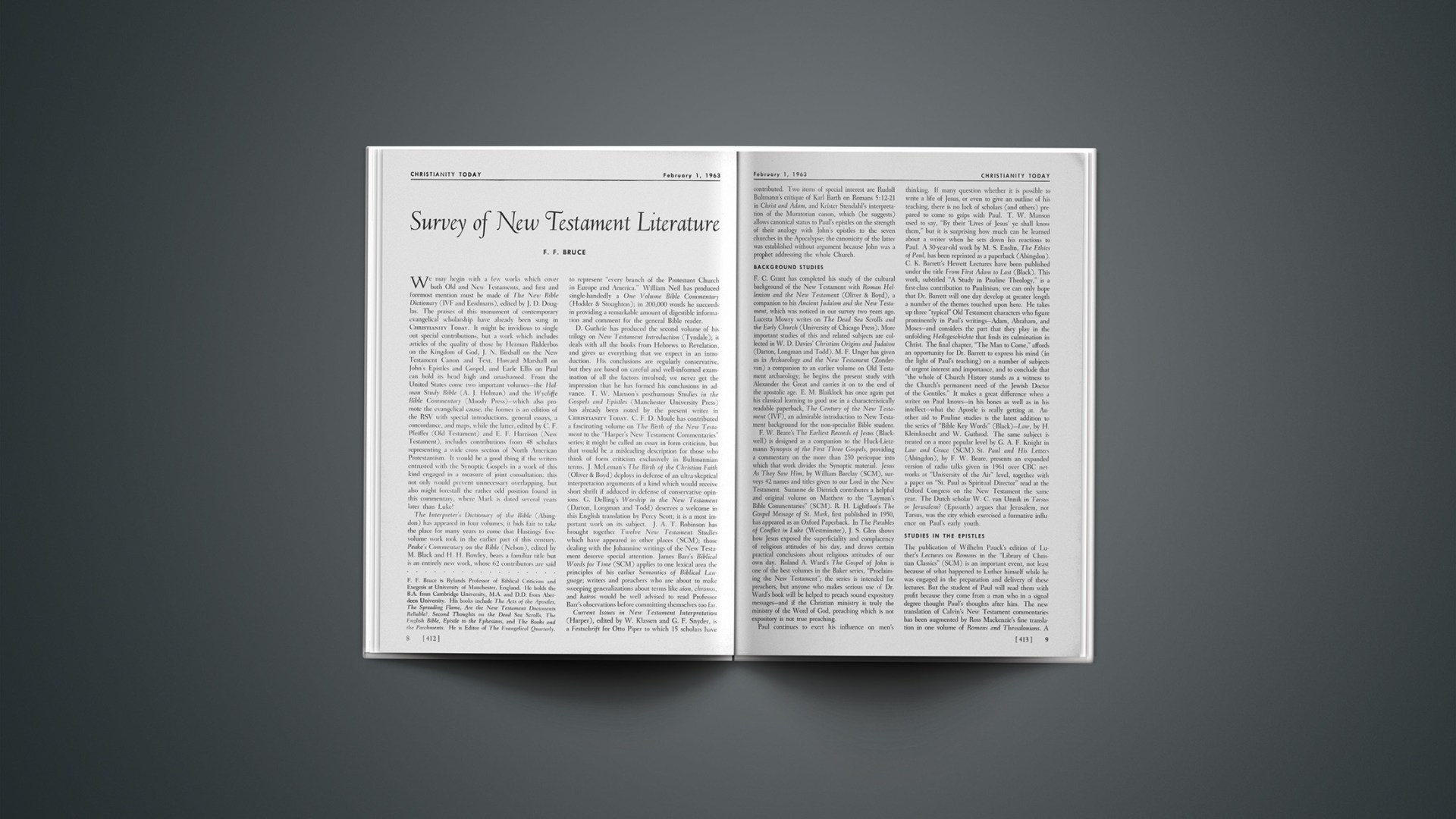

We may begin with a few works which cover both Old and New Testaments, and first and foremost mention must be made of The New Bible Dictionary (IVF and Eerdmans), edited by J. D. Douglas. The praises of this monument of contemporary evangelical scholarship have already been sung in CHRISTIANITY TODAY. It might be invidious to single out special contributions, but a work which includes articles of the quality of those by Herman Ridderbos on the Kingdom of God, J. N. Birdsall on the New Testament Canon and Text, Howard Marshall on John’s Epistles and Gospel, and Earle Ellis on Paul can hold its head high and unashamed. From the United States come two important volumes—the Holman Study Bible (A. J. Holman) and the Wycliffe Bible Commentary (Moody Press)—which also promote the evangelical cause; the former is an edition of the RSV with special introductions, general essays, a concordance, and maps, while the latter, edited by C. F. Pfeiffer (Old Testament) and E. F. Harrison (New Testament), includes contributions from 48 scholars representing a wide cross section of North American Protestantism. It would be a good thing if the writers entrusted with the Synoptic Gospels in a work of this kind engaged in a measure of joint consultation; this not only would prevent unnecessary overlapping, but also might forestall the rather odd position found in this commentary, where Mark is dated several years later than Luke!

The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (Abingdon) has appeared in four volumes; it bids fair to take the place for many years to come that Hastings’ five-volume work took in the earlier part of this century. Peake’s Commentary on the Bible (Nelson), edited by M. Black and H. H. Rowley, bears a familiar title but is an entirely new work, whose 62 contributors are said to represent “every branch of the Protestant Church in Europe and America”. William Neil has produced single-handedly a One Volume Bible Commentary (Hodder & Stoughton); in 200,000 words he succeeds in providing a remarkable amount of digestible information and comment for the general Bible reader.

D. Guthrie has produced the second volume of his trilogy on New Testament Introduction (Tyndale); it deals with all the books from Hebrews to Revelation, and gives us everything that we expect in an introduction. His conclusions are regularly conservative, but they are based on careful and well-informed examination of all the factors involved; we never get the impression that he has formed his conclusions in advance. T. W. Manson’s posthumous Studies in the Gospels and Epistles (Manchester University Press) has already been noted by the present writer in CHRISTIANITY TODAY. C. F. D. Moule has contributed a fascinating volume on The Birth of the New Testament to the “Harper’s New Testament Commentaries” series; it might be called an essay in form criticism, but that would be a misleading description for those who think of form criticism exclusively in Bultmannian terms. J. McLeman’s The Birth of the Christian Faith (Oliver & Boyd) deploys in defense of an ultra-skeptical interpretation arguments of a kind which would receive short shrift if adduced in defense of conservative opinions. G. Delling’s Worship in the New Testament (Darton, Longman and Todd) deserves a welcome in this English translation by Percy Scott; it is a most important work on its subject. J. A. T. Robinson has brought together Twelve New Testament Studies which have appeared in other places (SCM); those dealing with the Johannine writings of the New Testament deserve special attention. James Barr’s Biblical Words for Time (SCM) applies to one lexical area the principles of his earlier Semantics of Biblical Language; writers and preachers who are about to make sweeping generalizations about terms like aion, chronos, and kairos would be well advised to read Professor Barr’s observations before committing themselves too far.

Current Issues in New Testament Interpretation (Harper), edited by W. Klassen and G. F. Snyder, is a Festschrift for Otto Piper to which 15 scholars have contributed. Two items of special interest are Rudolf Bultmann’s critique of Karl Barth on Romans 5:12–21 in Christ and Adam, and Krister Stendahl’s interpretation of the Muratorian canon, which (he suggests) allows canonical status to Paul’s epistles on the strength of their analogy with John’s epistles to the seven churches in the Apocalypse; the canonicity of the latter was established without argument because John was a prophet addressing the whole Church.

Background Studies

F. C. Grant has completed his study of the cultural background of the New Testament with Roman Hellenism and the New Testament (Oliver & Boyd), a companion to his Ancient Judaism and the New Testament, which was noticed in our survey two years ago. Lucetta Mowry writes on The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Early Church (University of Chicago Press). More important studies of this and related subjects are collected in W. D. Davies’ Christian Origins and Judaism (Darton, Longman and Todd). M. F. Unger has given us in Archaeology and the New Testament (Zondervan) a companion to an earlier volume on Old Testament archaeology; he begins the present study with Alexander the Great and carries it on to the end of the apostolic age. E. M. Blaiklock has once again put his classical learning to good use in a characteristically readable paperback, The Century of the New Testament (IVF), an admirable introduction to New Testament background for the non-specialist Bible student.

F. W. Beare’s The Earliest Records of Jesus (Blackwell) is designed as a companion to the Huck-Lietzmann Synopsis of the First Three Gospels, providing a commentary on the more than 250 pericopae into which that work divides the Synoptic material. Jesus As They Saw Him, by William Barclay (SCM), surveys 42 names and titles given to our Lord in the New Testament. Suzanne de Diétrich contributes a helpful and original volume on Matthew to the “Layman’s Bible Commentaries” (SCM). R. H. Lightfoot’s The Gospel Message of St. Mark, first published in 1950, has appeared as an Oxford Paperback. In The Parables of Conflict in Luke (Westminster), J. S. Glen shows how Jesus exposed the superficiality and complacency of religious attitudes of his day, and draws certain practical conclusions about religious attitudes of our own day. Roland A. Ward’s The Gospel of John is one of the best volumes in the Baker series, “Proclaiming the New Testament”; the series is intended for preachers, but anyone who makes serious use of Dr. Ward’s book will be helped to preach sound expository messages—and if the Christian ministry is truly the ministry of the Word of God, preaching which is not expository is not true preaching.

Paul continues to exert his influence on men’s thinking. If many question whether it is possible to write a life of Jesus, or even to give an outline of his teaching, there is no lack of scholars (and others) prepared to come to grips with Paul. T. W. Manson used to say, “By their ‘Lives of Jesus’ ye shall know them,” but it is surprising how much can be learned about a writer when he sets down his reactions to Paul. A 30-year-old work by M. S. Enslin, The Ethics of Paul, has been reprinted as a paperback (Abingdon). C. K. Barrett’s Hewett Lectures have been published under the title From First Adam to Last (Black). This work, subtitled “A Study in Pauline Theology,” is a first-class contribution to Paulinism; we can only hope that Dr. Barrett will one day develop at greater length a number of the themes touched upon here. He takes up three “typical” Old Testament characters who figure prominently in Paul’s writings—Adam, Abraham, and Moses—and considers the part that they play in the unfolding Heilsgeschichte that finds its culmination in Christ. The final chapter, “The Man to Come,” affords an opportunity for Dr. Barrett to express his mind (in the light of Paul’s teaching) on a number of subjects of urgent interest and importance, and to conclude that “the whole of Church History stands as a witness to the Church’s permanent need of the Jewish Doctor of the Gentiles.” It makes a great difference when a writer on Paul knows—in his bones as well as in his intellect—what the Apostle is really getting at. Another aid to Pauline studies is the latest addition to the series of “Bible Key Words” (Black)—Law, by H. Kleinknecht and W. Gutbrod. The same subject is treated on a more popular level by G. A. F. Knight in Law and Grace (SCM). St. Paul and His Letters (Abingdon), by F. W. Beare, presents an expanded version of radio talks given in 1961 over CBC networks at “University of the Air” level, together with a paper on “St. Paul as Spiritual Director” read at the Oxford Congress on the New Testament the same year. The Dutch scholar W. C. van Unnik in Tarsus or Jerusalem? (Epworth) argues that Jerusalem, not Tarsus, was the city which exercised a formative influence on Paul’s early youth.

Studies In The Epistles

The publication of Wilhelm Pauck’s edition of Luther’s Lectures on Romans in the “Library of Christian Classics” (SCM) is an important event, not least because of what happened to Luther himself while he was engaged in the preparation and delivery of these lectures. But the student of Paul will read them with profit because they come from a man who in a signal degree thought Paul’s thoughts after him. The new translation of Calvin’s New Testament commentaries has been augmented by Ross Mackenzie’s fine translation in one volume of Romans and Thessalonians. A new book by E. K. Lee, A Study in Romans (SPCK), is not a commentary but a study of the principal themes of the epistle, viewed against a broad background. In the “Layman’s Bible Commentaries” (SCM), K. J. Foreman has written the volume on Romans, Corinthians. To write on three such important epistles in less than 150 pages means that many important matters must be dealt with but sketchily; nevertheless, Professor Foreman provides an attractive introduction to them for more elementary readers. A full-scale commentary on I Corinthians is J. Héring’s The First Epistle of Saint Paul to the Corinthians (Epworth), translated from the French. Like everything else by this veteran New Testament scholar, this commentary takes its place in the front rank. The only volume in the “New International Commentary on the New Testament” to appear this year is Philip E. Hughes’s magisterial volume on II Corinthians (Eerdmans). Whereas Professor Héring argues for the dichotomy of an epistle which is usually acknowledged to be a unity, Dr. Hughes argues ably for the unity of an epistle in which many exegetes, even if they are generally conservative in their approach, recognize portions of at least two Pauline letters. In the future Dr. Hughes’s arguments will have to be seriously considered, not only on this point but on many others which affect the interpretation of II Corinthians. At this point it will not be out of place to record our indebtedness to the late General Editor of the “New International Commentary,” Dr. N. B. Stonehouse, and our sense of the loss which New Testament scholarship has suffered by his death.

One short passage in Galatians—the catalog of the works of the flesh and the fruit of the Spirit in 5:19–23—is the subject of William Barclay’s Flesh and Spirit (SCM), a word-study of all the terms used in these verses. Karl Barth’s Philippians, first published in German in 1927, has appeared in an English dress (SCM); it tells us at least as much about the development of Barth’s thought as it does about the teaching of Paul. William Hendriksen’s volume on Philippians has appeared in his New Testament Commentary (Baker); in it, as we expect, we have ample evidence of the painstaking exegete and the Christian Reformed theologian. L. J. Baggott’s New Approach to Colossians (Mowbrays) takes the cosmic significance of Christ seriously and endeavors to show how Christ today provides the only clue to a satisfying interpretation of this mysterious universe. A simpler work on Colossians is H. K. Moulton’s volume on it in the Epworth “Preacher’s Commentaries.” C. K. Barrett has written on the Pastoral Epistles for “The New Clarendon Bible” (Oxford) what is claimed to be the first commentary based on the New English Bible.

The “Torch” commentary on The Epistles of John (SCM) has been written by Neil Alexander. He expresses his indebtedness to C. H. Dodd’s work on these epistles, but dissents from his ascription of them to a different author from the Fourth Gospel’s. Lehmann Strauss has produced a devotional exposition of the same epistles (Loizeaux). D. T. Niles of Ceylon has written a work on the Book of Revelation entitled As Seeing the Invisible (SCM). He makes no independent contribution to the critical questions raised by the book, but helps the reader to read it so as with John to see Him who is invisible. William Hendriksen’s exposition of the same book, More than Conquerors, now over 20 years old, has appeared in a British edition (Tyndale Press).

H. W. Montefiore has published a most interesting series of studies in Josephus and the New Testament (Mowbrays), in which he considers how far certain supernatural events associated with the birth, death, and resurrection of Christ can be correlated with prodigies related by Josephus. The same author collaborates with H. E. W. Turner in the writing of Thomas and the Evangelists (SCM), which studies the relationship between the Gnostic “Gospel according to Thomas” and the canonical Gospels. The two authors reach somewhat different conclusions, so that the reader is faced by the healthy task of exercising his private judgment. Another important work on the recently discovered Gnostic texts is an edition of The Gospel of Philip (Mowbrays), by R. McL. Wilson.

END

Pilate Before Christ

The bench is raised

Where Pilate judging sat,

And Christ in seamless robe

Wrist-bound with sneers

In quiet dignity and strange repose

With unbefitting majesty yet speaks

Where common clay would agitate,

“Against me Thou

Couldst have no power

Save it were given from above.”

O Pilate, in those words

Deliverance lies

From trial more your own

Than Christ’s!

For many choose with you

The empty motions

Of hand-washing indecision,

And many vainly cry

Irresolute:

“What shall I do with Christ?”

RUTHE T. SPINNANGER