Christ is the first fruits of our resurrection. By understanding what happened on the first Easter morning we gain insight into the meaning of our eternal destiny. Because it is this way and not the other way around, the same may be said concerning the meaning of death. We cannot understand Jesus’ death by looking at our own death, but we can gain comprehension of our own death from the death on the Cross.

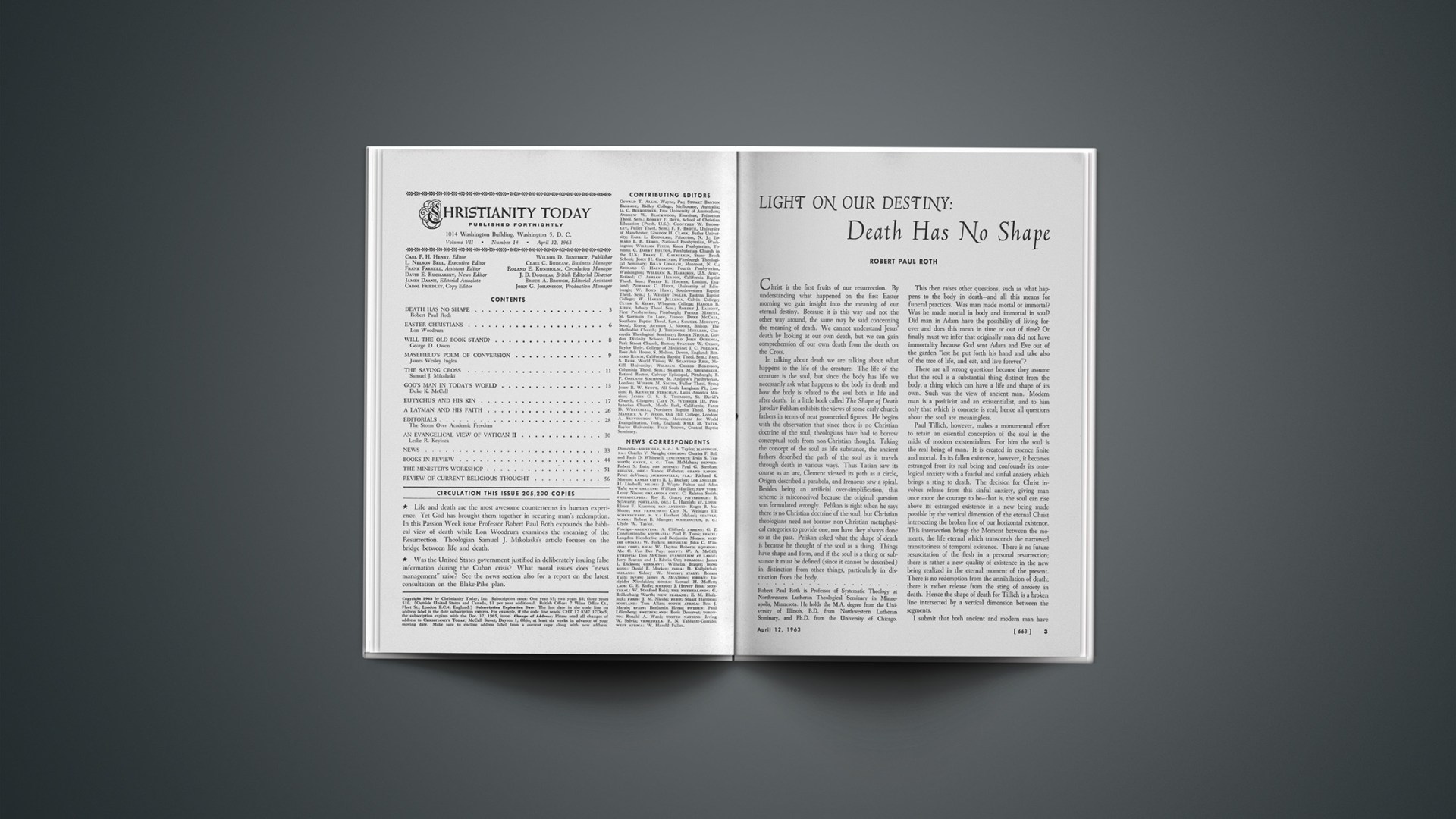

In talking about death we are talking about what happens to the life of the creature. The life of the creature is the soul, but since the body has life we necessarily ask what happens to the body in death and how the body is related to the soul both in life and after death. In a little book called The Shape of Death Jaroslav Pelikan exhibits the views of some early church fathers in terms of neat geometrical figures. He begins with the observation that since there is no Christian doctrine of the soul, theologians have had to borrow conceptual tools from non-Christian thought. Taking the concept of the soul as life substance, the ancient fathers described the path of the soul as it travels through death in various ways. Thus Tatian saw its course as an arc, Clement viewed its path as a circle, Origen described a parabola, and Irenaeus saw a spiral. Besides being an artificial over-simplification, this scheme is misconceived because the original question was formulated wrongly. Pelikan is right when he says there is no Christian doctrine of the soul, but Christian theologians need not borrow non-Christian metaphysical categories to provide one, nor have they always done so in the past. Pelikan asked what the shape of death is because he thought of the soul as a thing. Things have shape and form, and if the soul is a thing or substance it must be defined (since it cannot be described) in distinction from other things, particularly in distinction from the body.

This then raises other questions, such as what happens to the body in death—and all this means for funeral practices. Was man made mortal or immortal? Was he made mortal in body and immortal in soul? Did man in Adam have the possibility of living forever and does this mean in time or out of time? Or finally must we infer that originally man did not have immortality because God sent Adam and Eve out of the garden “lest he put forth his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat, and live forever”?

These are all wrong questions because they assume that the soul is a substantial thing distinct from the body, a thing which can have a life and shape of its own. Such was the view of ancient man. Modern man is a positivist and an existentialist, and to him only that which is concrete is real; hence all questions about the soul are meaningless.

Paul Tillich, however, makes a monumental effort to retain an essential conception of the soul in the midst of modern existentialism. For him the soul is the real being of man. It is created in essence finite and mortal. In its fallen existence, however, it becomes estranged from its real being and confounds its ontological anxiety with a fearful and sinful anxiety which brings a sting to death. The decision for Christ involves release from this sinful anxiety, giving man once more the courage to be—that is, the soul can rise above its estranged existence in a new being made possible by the vertical dimension of the eternal Christ intersecting the broken line of our horizontal existence. This intersection brings the Moment between the moments, the life eternal which transcends the narrowed transitoriness of temporal existence. There is no future resuscitation of the flesh in a personal resurrection; there is rather a new quality of existence in the new being realized in the eternal moment of the present. There is no redemption from the annihilation of death; there is rather release from the sting of anxiety in death. Hence the shape of death for Tillich is a broken line intersected by a vertical dimension between the segments.

I submit that both ancient and modern man have views diametrically opposed to the Christian view set forth in the Bible. The Bible, it is true, does not have a metaphysic of the soul, for the soul is simply the life of the creature. The soul is not something distinct from the body; it is the body insofar as the body lives. Man is not a soul which has a body, nor is he a body which has a soul. He is a creature who comes into existence by the Word of God and continues in existence only as long as God speaks. He has neither mortality nor immortality in himself, but he has life insofar as God says so. The soul does not have a substantial or essential being which could conceivably be either preexistent or immortal. The soul has a given existence from the creative Word and Spirit of God, an existence which depends for its life each moment on the gracious divine locution. But because of man’s rebellious disobedience this existence has been separated from God. The existence itself is not in jeopardy. If it were, suicide might be a way out. Since it is not, suicide only widens the separation. This is the meaning of death: separation from God the source of life. Death is not annihilation, not the passing from being to nothing, not the fall from essence to estranged existence. Death is the fall away from God, the separation of the creature from the creative and comforting Word of life.

Death In Three Stages

Since the creature is a unity and not a duality of body and soul nor a trichotomy of body, soul, and spirit, death means separation of the whole man from God. Hence Paul can speak of the man who is still breathing as walking in death: “You he made alive while you were yet dead in the trespasses and sin in which you once walked following the course of this world.” Death as separation from God then has various stages. The Bible speaks of death accordingly in three ways:

1. There is the death which we share with the whole of fallen creation and in which we now walk as sinners even though we still breathe.

2. There is the death which we experience as the cessation of our earthly functions. Because we see the decay of physical death we tend to think of it as a passing into oblivion. We fight against this by embalming the deceased and buying expensive concrete vaults to extend the semblance of physical life as long as possible. While an expensive ointment may be rightly used to perfume a corpse for its burial, this should never degenerate into a fearful disbelief in the new heaven and new earth in which all things are made new. But what does the Bible mean when it speaks of the place of departed spirits? Does death after all bring a rending of the flesh from the spirit such that while the flesh molders in the grave the spirit dwells as a shadow shape in some mysterious realm of the dead? This is precisely the idea: in death the flesh is returned to dust and the real person is shorn of his shape. Although personal consciousness survives, the person becomes a shapeless shadow. But the work of Christ in regeneration is to give us bodily shape until the final resurrection, when we shall be raised with incorruptible bodies. Paul affirms this in Ephesians when he speaks of Christ’s leading a host of captives out of the captivity of death. Peter also speaks of Christ’s preaching to those imprisoned in death. And to the Corinthians Paul speaks of the flesh as an earthly tent which he longs to put off so that he can put on Christ. Actually the biblical conception of the place of departed spirits does not give credence to the concept of a substantial soul. It deepens the meaning of the splitting separation of death which now is seen to be a separation not only from God and our fellows but even from ourselves.

3. Finally there is the “second” death or the death of the last judgment, which is an ultimate separation in outer darkness. Even here there is no indication in Scripture of extinction, though this is not completely unthinkable. Thus death in all three senses has a double dimension: it is the wage of sin and it is the mark of our estranged transience. Death is both a judgment and a willful separation. God did not create us with mortality. This would be to say that God created us separated from himself. Death is an enemy that intervened between us and God, and the path of the soul is to return to fellowship with God when that enemy has been vanquished. This has been accomplished by Christ, and it is effective for us when we are joined to him as members of his body in the Church. We can pass through death with him and rise in newness of life even as he is the first fruits of the resurrection.

And the marvel of our faith is that we have a sacrament (guarantee) of this already in this present stage of our journey. The symbol of the Christian understanding of the life and death of the soul is a broken line which is intersected in one of its moments (not between the moments) where Christ became flesh, and the moments of my life are joined to that redeeming moment through the re-presenting of Christ in the moment of the Eucharist in which Christ gives himself both to God in continuous intercession and to us, the celebrating congregation. As the broken moments of historical time are united in the eternity of Christ’s intercession, so the broken bits of bread join my flesh and guarantee the restoration of my real self with the real presence of Christ.

If we wish to understand the meaning of death and the destiny of the soul, we must look to the death and resurrection of Christ. For him death was an enemy of both God and man. Socrates found death to be a friend, and he drank the poison hemlock gladly because he thought it would release him from the fetters of his flesh. Jesus fought death with all his might. His soul was anxious, troubled, heavy with sorrow. He met death crying out bitterly in the night: “Father, if it be possible let this cup pass from my lips.” But then from the cross with a final loud shout he refused to give death the victory, saying: “Father, into thy hands I commit my spirit.” Not into the hands of the enemy death does Jesus give his forsaken spirit, but into the hands of his Father.

Just as in death the whole man dies, not just the body of flesh as Socrates thought, so likewise the whole man rises in the resurrection, not just the soul. This is the meaning of the Empty Tomb, and hence we confess in our creed that we believe in the resurrection of the body. But this is not to say, as some might think, that Jesus’ flesh was merely resuscitated. This is what Lazarus experienced, only to die again. In the resurrection a new creature is made with a body that is clothed in incorruptibility instead of in corruptible flesh. Thus the risen Lord was quite different from the raised Lazarus. He was not limited by the simple location of space and time. He appeared not to all, but only to those chosen by God (Acts 10:41). Yet he had bodily shape, and he ate and drank with his disciples.

On this model we may say that in the separation of death our flesh becomes a corpse and returns to the dust of the earth. Our tombs become empty, too, and our spirits go to the place of the departed spirits. But if we in faith belong to Christ, then we shall be with him in paradise. Without flesh, since our flesh is moldering in the grave, we wait for the last day when we will be raised with all the dead and given new bodies which are holy. In the meantime we rest with Christ in paradise clothed with the body of Christ. We are hid with Christ in God, as Paul says. We are not naked disembodied spirits. We are dressed in the goodness of Christ, and we walk with him from glory unto glory.

END

STRAWS IN THE WIND

THE WINDS ARE BLOWING—You might call these “straws in the wind,” little indicators of which way the religious winds are blowing.

The first of these “straws” appeared in Life magazine last year when they presented the pictures of the one hundred outstanding young men in America. Young clergymen were conspicuous by their absence. Rev. Martin Luther King was the rare exception. One wonders what this augurs for the Church in years ahead.

The second “straw” was called to our attention a few days ago by Casper Nannes of the Washington Star. He observed that in listing the Ten Top News Stories of 1962 no religious event was considered of major importance to break into this listing. Yet he mentioned that 1962 saw the Supreme Court hand down its ruling on the New York Regents’ prayer in school, a decision that had terrific reactions everywhere in America. 1962 also saw Pope John XXIII call the first Vatican Council in over one hundred years, and Time magazine had featured Pope John as The Man of the Year. Both of these stories were missing from the Top Ten.

The third “straw” is the President’s tax reform program. It has been pointed out that whereas presently up to 30 per cent of income can be deducted for contributions to church and charitable organizations, the pending tax reform “proposes a 5 per cent floor on itemized deductions to non-profit groups.” This would deal a blow to church support that would be devastating. Particularly would this be so, coming at the same time when the churches must face the probability of the removal of exemption from taxes on their property.

The fourth “straw” is the Monday morning report of the sermons in the Washington Post which is usually consigned to the obituary page. This is an affinity that is not very flattering, and furnishes another insight as to the place the Word of God has in the eyes of an influential newspaper.

I am not sure just what all these things say, but it would be hard to argue from them that we put much of a priority on the Church.—Dr. LEE SHANE, Minister, National Baptist Memorial Church, Washington, D. C.

SPECKS ON A STAR—Five nations lead the world in alcoholism, a high divorce rate, juvenile delinquency, and mental illness. These are the United States, Switzerland, Britain, Denmark, and France. These are the western nations which have it made. None of us are starving. But not all is well with us. What we are going through is a religious conflict. Physically, we are advancing. Every day there is a better chance we will live longer. We have improved social skills. And we are intellectually gifted. Any generation that can invent something to wipe out civilization isn’t stupid.

With all this the prevailing mood is that we are specks thrown on a third-rate star, and life is empty and without meaning or purpose. The ultimate thing about a culture is its religion. What does it believe? What are its values? What is its faith?—Bishop GERALD KENNEDY, Past President, The Methodist Council of Bishops.

LAST ON THE LIST—In medieval times they debated whether an archdeacon, involved as he necessarily was with matters of property and finance, could hope to be saved. Today also, there are many who would question whether a man who occupies an archbishopric and who is thereby plunged into a whirl of organizations and public appearances, can hope to exercise an evangelistic ministry.—PAUL JACKSON in Outlook, London.

WHO COULD ASK FOR MORE?—Based upon the latest archaeological research, this illuminating book by a distinguished editorial board contains over 100,000 words of text. The entire work is non-theological.—Advertisement for Our Living Bible, quoted in Prism, London.