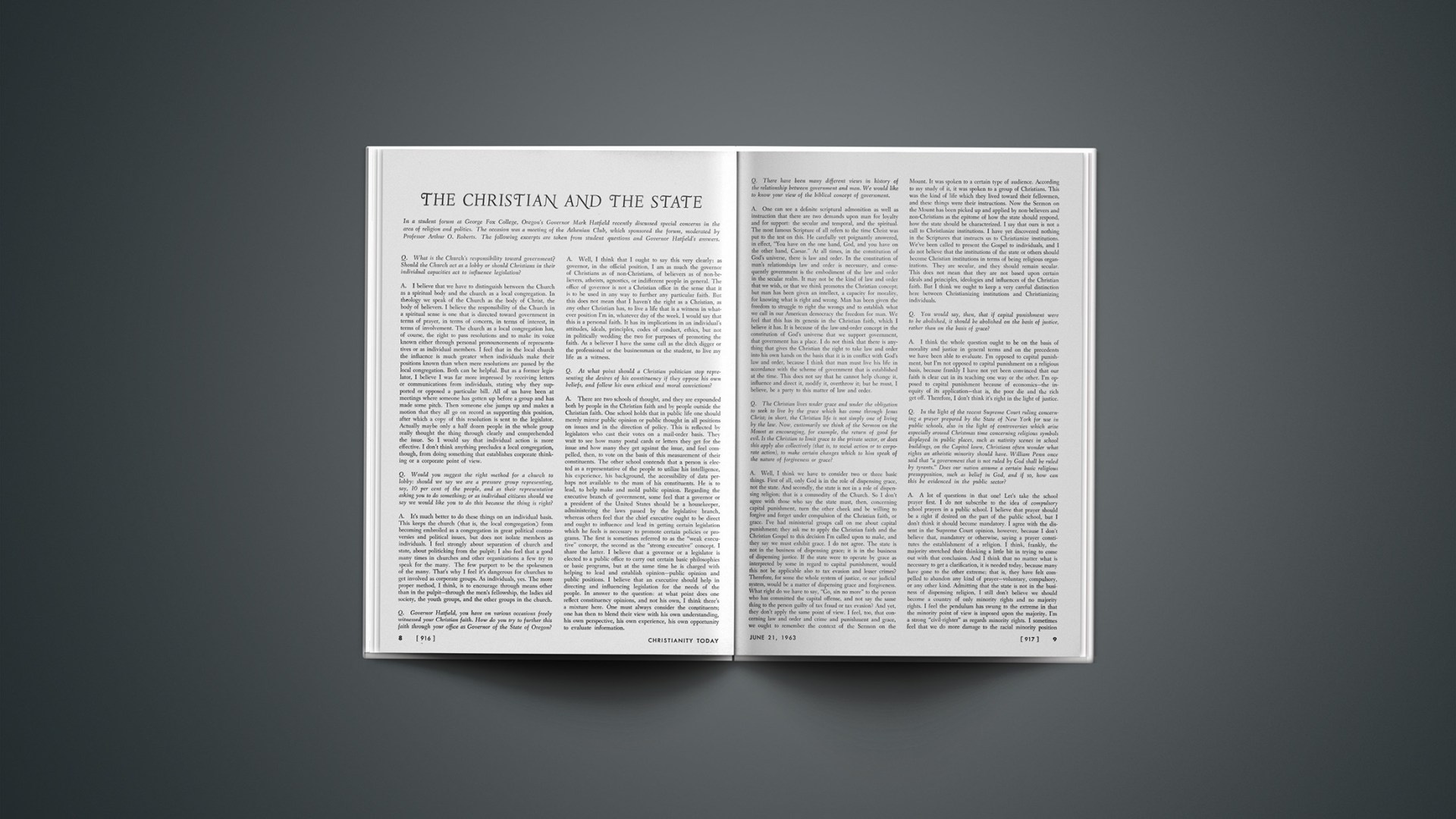

In a student forum at George Fox College, Oregon's Governor Mark Hatfield recently discussed special concerns in the area of religion and politics. The occasion was a meeting of the Athenian Club, which sponsored the forum, moderated by Professor Arthur O. Roberts. The following excerpts are taken from student questions and Governor Hatfield's answers.

Q. What is the Church's responsibility toward government? Should the Church act as a lobby or should Christians in their individual capacities act to influence legislation?

A. I believe that we have to distinguish between the Church as a spiritual body and the church as a local congregation. In theology we speak of the Church as the body of Christ, the body of believers. I believe the responsibility of the Church in a spiritual sense is one that is directed toward government in terms of prayer, in terms of concern, in terms of interest, in terms of involvement.

The church as a local congregation has, of course, the right to pass resolutions and to make its voice known either through personal pronouncements of representatives or as individual members. I feel that in the local church the influence is much greater when individuals make their positions known than when mere resolutions are passed by the local congregation. Both can be helpful.

But as a former legislator, I believe I was far more impressed by receiving letters or communications from individuals, stating why they supported or opposed a particular bill. All of us have been at meetings where someone has gotten up before a group and has made some pitch. Then someone else jumps up and makes a motion that they all go on record as supporting this position, after which a copy of this resolution is sent to the legislator. Actually maybe only a half dozen people in the whole group really thought the thing through clearly and comprehended the issue. So I would say that individual action is more effective. I don't think anything precludes a local congregation, though, from doing something that establishes corporate thinking or a corporate point of view.

Q. Would you suggest the right method for a church to lobby: should we say we are a pressure group representing, say, 10 percent of the people, and as their representative asking you to do something; or as individual citizens should we say we would like you to do this because the thing is right?

A. It's much better to do these things on an individual basis. This keeps the church (that is, the local congregation) from becoming embroiled as a congregation in great political controversies and political issues, but does not isolate members as individuals. I feel strongly about separation of church and state, about politicking from the pulpit; I also feel that a good many times in churches and other organizations a few try to speak for the many: the few purport to be the spokesmen of the many. That's why I feel it's dangerous for churches to get involved as corporate groups. As individuals, yes. The more proper method, I think, is to encourage through means other than in the pulpit–through the men's fellowship, the ladies aid society, the youth groups, and the other groups in the church.

Q. Governor Hatfield, you have on various occasions freely witnessed your Christian faith. How do you try to further this faith through your office as Governor of the State of Oregon?

A. Well, I think that I ought to say this very clearly: as governor, in the official position, I am as much the governor of Christians as of non-Christians, of believers as of non-believers, atheists, agnostics, or indifferent people in general. The office of governor is not a Christian office in the sense that it is to be used in any way to further any particular faith. But this does not mean that I haven't the right as a Christian, as any other Christian has, to live a life that is a witness in whatever position I'm in, whatever day of the week.

I would say that this is a personal faith. It has its implications in an individual's attitudes, ideals, principles, codes of conduct, ethics, but not in politically wedding the two for purposes of promoting the faith. As a believer I have the same call as the ditch digger or the professional or the businessman or the student: to live my life as a witness.

Q. At what point should a Christian. politician stop representing the desires of his constituency if they oppose his own beliefs, and follow his own ethical and moral convictions?

A. There are two schools of thought, and they are expounded both by people in the Christian faith and by people outside the Christian faith. One school holds that in public life one should merely mirror public opinion or public thought in all positions on issues and in the direction of policy. This is reflected by legislators who cast their votes on a mail-order basis. They wait to see how many postal cards or letters they get for the issue and how many they get against the issue, and feel compelled, then, to vote on the basis of this measurement of their constituents.

The other school contends that a person is elected as a representative of the people to utilize his intelligence, his experience, his background, the accessibility of data perhaps not available to the mass of his constituents. He is to lead, to help make and mold public opinion. Regarding the executive branch of government, some feel that a governor or a president of the United States should be a housekeeper, administering the laws passed by the legislative branch, whereas others feel that the chief executive ought to be direct and ought to influence and lead in getting certain legislation which he feels is necessary to promote certain policies or programs. The first is sometimes referred to as the "weak executive" concept, the second as the "strong executive" concept. I share the latter.

I believe that a governor or a legislator is elected to a public office to carry out certain basic philosophies or basic programs, but at the same time he is charged with helping to lead and establish opinion–public opinion and public positions. I believe that an executive should help in directing and influencing legislation for the needs of the people. In answer to the question: at what point does one reflect constituency opinions, and not his own, I think there's a mixture here. One must always consider the constituents; one has then to blend their view with his own understanding, his own perspective, his own experience, his own opportunity to evaluate information.

Q. There have been many different views in history of the relationship between government and man. We would like to know your view of the biblical concept of government.

A. One can see a definite scriptural admonition as well as instruction that there are two demands upon man for loyalty and for support: the secular and temporal, and the spiritual. The most famous Scripture of all refers to the time Christ was put to the test on this. He carefully yet poignantly answered, in effect, "You have on the one hand, God, and you have on the other hand, Caesar." At all times, in the constitution of God's universe, there is law and order. In the constitution of man's relationships, law and order is necessary, and consequently government is the embodiment of the law and order in the secular realm. It may not be the kind of law and order that we wish, or that we think promotes the Christian concept; but man has been given an intellect, a capacity for morality, for knowing what is right and wrong.

Man has been given the freedom to struggle to right the wrongs and to establish what we call in our American democracy the freedom for man. We feel that this has its genesis in the Christian faith, which I believe it has. It is because of the law-and-order concept in the constitution of God's universe that we support government, that government has a place. I do not think that there is anything that gives the Christian the right to take law and order into his own hands on the basis that it is in conflict with God's law and order, because I think that man must live his life in accordance with the scheme of government that is established at the time. This does not say that he cannot help change it, influence and direct it, modify it, overthrow it; but he must, I believe, be a Party to this matter of law and order.

Q. The Christian lives under grace and under the obligation to seek to live by the grace which has come through Jesus Christ; in short, the Christian life is not simply one of living by the law. Now, customarily we think of the Sermon on the Mount as encouraging, for example, the return of good for evil. Is the Christian to limit grace to the private sector, or does this apply also collectively (that is, to social action or to corporate action), to make certain changes which to him speak of the nature of forgiveness or grace?

A. Well, I think we have to consider two or three basic things. First of all, only God is in the role of dispensing grace, not the state. And secondly, the state is not in a role of dispensing religion; that is a commodity of the Church. So I don't agree with those who say the state must, then, concerning capital punishment, turn the other cheek and be willing to forgive and forget under compulsion of the Christian faith, or grace.

I've had ministerial groups call on me about capital punishment; they ask me to apply the Christian faith and the Christian Gospel to this decision I'm called upon to make, and they say we must exhibit grace. I do not agree. The state is not in the business of dispensing grace; it is in the business of dispensing justice. If the state were to operate by grace as interpreted by some in regard to capital punishment, would this not be applicable also to tax evasion and lesser crimes? Therefore, for some the whole system of justice, or our judicial system, would be a matter of dispensing grace and forgiveness. What right do we have to say, "Go, sin no more" to the person who has committed the capital offense, and not say the same thing to the person guilty of tax fraud or tax evasion? And yet, they don't apply the same point of view.

I feel, too, that concerning law and order and crime and punishment and grace, we ought to remember the context of the Sermon on the Mount. It was spoken to a certain type of audience. According to my study of it, it was spoken to a group of Christians. This was the kind of life which they lived toward their fellow men, and these things were their instructions. Now the Sermon on the Mount has been picked up and applied by non-believers and non-Christians as the epitome of how the state should respond, how the state should be characterized.

I say that ours is not a call to Christianize institutions. I have as of yet discovered nothing in the Scriptures that instructs us to Christianize institutions. We've been called to present the Gospel to individuals, and I do not believe that the institutions of the state or others should become Christian institutions in terms of being religious organizations. They are secular, and they should remain secular. This does not mean that they are not based upon certain ideals and principles, ideologies and influences of the Christian faith. But I think we ought to keep a very careful distinction here between Christianizing institutions and Christianizing individuals.

Q. You would say, then, that if capital punishment were to be abolished, it should be abolished on the basis of justice, rather than on the basis of grace?

A. I think the whole question ought to be on the basis of morality and justice in general terms and on the precedents we have been able to evaluate. I'm opposed to capital punishment, but I'm not opposed to capital punishment on a religious basis, because frankly I have not yet been convinced that our faith is clear cut in its teaching one way or the other. I'm opposed to capital punishment because of economics—the inequity of its application—that is, the poor die and the rich get off. Therefore, I don't think it's right in the light of justice.

Q. In the light of the recent Supreme Court ruling concerning a prayer prepared by the State of New York for use in public schools, also in the light of controversies which arise especially around Christmas time concerning religious symbols displayed in public places, such as nativity scenes in school buildings, on the Capitol lawn, Christians often wonder what rights an atheistic minority should have. William Penn once said that "a government that is not ruled by God shall be ruled by tyrants." Does our nation assume a certain basic religious presupposition, such as belief in God, and so, how can this be evidenced in the public sector?

A. A lot of questions in that one! Let's take the school prayer first. I do not subscribe to the idea of compulsory school prayers in a public school. I believe that prayer should be a right if desired on the part of the public school, but I don't think it should become mandatory. I agree with the dissent in the Supreme Court opinion, however, because I don't believe that, mandatory or otherwise, saying a prayer constitutes the establishment of a religion. I think, frankly, the majority stretched their thinking a little bit in trying to come out with that conclusion. And I think that no matter what is necessary to get a clarification, it is needed today, because many have gone to the other extreme; that is, they have felt compelled to abandon any kind of prayer—voluntary, compulsory, or any other kind. Admitting that the state is not in the business of dispensing religion, I still don't believe we should become a country of only minority rights and no majority rights.

I feel the pendulum has swung to the extreme in that the minority point of view is imposed upon the majority. I'm a strong "civil-righter" as regards minority rights. I sometimes feel that we do more damage to the racial minority position by talking of minorities and majorities rather than of human rights. I feel there is only one race, the human race; if we could lift our thinking to a new plane where we are talking of human rights straight across the yellow man's rights, black man's rights, white man's rights, and brown man's rights, but human rights, human liberties and human opportunities, I think we would he much better off. But then we get into this religious area, and we have the various religious minorities.

Again, I don't think that at any point a minority should be imposed upon by a majority. Rights should be protected. The majority has rights, too, and I think that in our efforts to establish particularly Negro rights and other minority rights we have moved into an era in which we have become so minority-oriented we've forgotten about the majority. And this is just as wrong as when we were concerned only about the majority and had no concern about the minority. The only way to keep this pendulum from swinging back and forth to the extremes, in my opinion, is to start thinking of human rights, of everybody's rights.

I am very much opposed to any attempt to force religion upon an atheistic person. By the same token merely I don't think to protect his right we ought all to be disenfranchised or have completely taken away from us our rights to apply certain philosophies and religious beliefs in our daily walk.

Now, you ask, are there presuppositions upon which the state, that is, our nation, is founded in religious principles and orientation to God? Well, I think very obviously we have this in all facets of our national life. You go back to the New England Confederation Act, you go back to the Mayflower Compact, you go to the Declaration of Independence: men are endowed with inalienable rights by their Creator—God-given, not man-given rights. I think this is a very interesting distinction: in our Declaration of Independence these were not rights to be achieved in War, these were not rights to be achieved by one group of men applying them and giving them to another man; these were rights given by God—God, the source of all freedom and all rights. He gave them to man.

So in our society today we signify these rights in many ritualistic and meaningful ways: "In God We Trust" on our coins, "one nation under God" as we pledge allegiance, and so on. We put our hand on the Bible, or we say, "So help me God," before we go into the witness chair in a court. There are many orientations in the direction of God. I frankly feel some of this has become more traditional, more ritualistic than spiritual. I think that originally it probably had great spiritual significance, and to some people today may still have, but the great mass of people now take it as rote experience.

Q. Throughout our history we have famous sayings of men dedicated to their principles: Nathan Hale, "I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country"; Patrick Henry, "Give me liberty or give me death." These have often been quoted. During World War II, the 442nd Infantry comprised of Japanese Americans whose parents were in concentration camps, had for its slogan, "Go for Broke." They had nothing to lose but to show that they were American citizens. They were within the total group of the mass population. How can a Christian, who feels an obligation to God and then also possibly an obligation to his fellowman, participate in party politics without compromising his stand as a Christian witness? In what specific ways may a Christian participate in party politics?

A. First of all, I think the question presupposes that being an integral part of political party organization implies a call for compromise or a conflict in the living of a Christian life. I think this is an error. I don't think that a person has to compromise his principles, his Christian faith, to become active in a political party—Democrat or Republican. I believe an attitude has sprung up within the church, especially within the evangelical church, that there is something sinister or worldly about politics, especially in the extent that a person thus associated is not living the so-called separated life.

I would like to make a point of theology here about the scriptural teaching on the separated life and on the Christian in the world. There is a vital and important difference between separation and isolation, and I think too many times evangelical Christians have confused isolation with separation. The First Letter to the Church at Corinth, fifth chapter and tenth verse (Weymouth translation), shows this very clearly. Paul is saying that their misinterpretation of his comments about separation would mean "then you would have to go out of the world altogether." They couldn't even stay on the globe.

Paul went on to explain that he spoke of separating from those who call themselves Christians those who are not living the life of a Christian. Separate yourselves from these people, Paul says, because they are bringing discredit to the whole Christian Faith. Now I feel this is a very important point, because this means that we have not only an opportunity, but also, I believe, an obligation as Christians to involve ourselves with the institutions of government, the institutions of our secular life, and our secular world, to witness, and to influence these institutions—not to "Christianize" the institutions, but to bring to bear the influence of Christian ideology, Christian ethics, Christian principles. I believe this should be done, first of all, with knowledge.

I believe that oftentimes Christians have had the attitude that as long as they took the Bible in one hand and went out the door like mad, they could immediately go into the ministry rather than going through a training program an educational experience. Too many times we have people not properly trained. And so it is in politics. We have some people who are most anxious to be active, but who do not take the time to train themselves, to educate themselves, to learn about the fundamentals and the importance of procedures and theories and doctrines and practices.

The Christian should always represent excellence in whatever he does. I think it is the poorest Christian witness in a Christian college when a student capable of making a B is content with a C. I think it's a poor witness when a church organization lets its building fall into disrepair and be a blight on the neighborhood. I think it's a poor Christian witness when a man in business does not pay his bills. I think it's a poor Christian witness whenever we have less than excellence as a characteristic of the life of the witness.

So, I would say a Christian in government or in teaching or in business or in anything else should represent the ultimate in excellence. This comes through education, through experience, and through participation. A Christian should enter in and be the best citizen. This doesn't mean every Christian has to go out and file for political office, but every Christian ought to be alert to the issues of the day, aware of the problems of his community. He ought to have the knowledge and the information necessary to establish a position, and then he ought to be active in helping to find solutions to these problems.

Q. As an activist, then, would this person be capable of participating, say, as a county chairman, a city precinct leader, a member of policy-formation committees for various parties?

A. Absolutely. I see no problem there at all. I think the problem in your mind, which you're not saying in public, and probably the problem in many a Christian's mind, is, "Does one have to engage in the social practices of politics?" I've had more people say to me, "Do you drink?" First of all, let me say that I don't, although non-drinking isn't necessarily the badge of Christianity. I think too many people put the badges on their breast and go boldly out into the community and say, "Look, I don't drink, I don't smoke, I don't do this, I don't do the other thing." They have all the "don'ts" lined right across in these beautiful badges, and therefore they consider themselves Christian.

Well, as I say, I think this is not the approach. This to me is the negative, legalistic approach that grace does not embody. I think it's a matter of heart, a matter of priority. I think a person is committed, first of all, to the person of Jesus Christ and is committed in the sense that he has given his total life. Then these outward appearances of the world or the non-Christian either fade away from the life or are eliminated some other way. You don't put yourself in that position first by saying, "God, now I don't smoke anymore, I don't drink anymore, so I am now ready to become a member of your family." This is not the approach.

Well, so it is in politics. Yes, there are cocktail parties; yes, liquors are served on many occasions; yes, there are people who are immoral with other people in different ways. Consequently, these are the things by which we characterize politics. But that doesn't mean that the Christian has to engage in these things. This doesn't mean that the person who is in the environment is going to blend in; he can still stand out like a sore thumb, and I would say this is true even of a used-car salesman. Does he have to gyp every man who comes into his used-car lot merely because he's in a business that is very competitive? Does every man in the legal profession have to be a shyster?

I don't think there's any difference between being a Christian in politics and being a Christian in any other legitimate secular pursuit. You have the immoral, you have the amoral, you have the shyster, you have the crooked, corrupt man and woman in any and every avenue of life. Why? Because there still is in the world. That doesn't mean that we can sit back and say, there's nothing I can do about it and therefore we'll just let things ride along. We ought to be out there about our Father's business in every legitimate secular pursuit.

God has called us into every line of work. He hasn't said, I've called the Christians to be isolated only in Christian institutions of higher learning, or I've called people to hide in church organizations. He has called Christians into every legitimate walk of life, every legitimate pursuit.

This article originally appeared in Christianity Today on June 21, 1963.

Copyright © 1963 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today interviewed Mark Hatfield for a 1982 cover story