The Editor

Ecumenical theologians climbed Mont Réal,

Ecumenical theologians had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put ecumenical theology together again.

The World Council’s fourth world Faith and Order Conference, held July 12–26 in Montreal, proved a major debacle whose defacing scars may long embarrass the ecumenical movement. In the aftermath of this fiasco (WCC leaders themselves privately labeled it “a crisis in technique”) the council’s Central Committee will now face the heavy burden of defining the future status of faith-and-order concerns.

The Montreal conclave doubtless had positive values: face-to-face meetings dispelling needless suspicion, frank exchange of contrary views, recognition that despite deep divergences delegates are sincerely devoted to Christian concerns in a non-Christian world, mounting uneasiness over the fragmented Christian witness, probing of areas of agreement as well as of difference between long-separated communions, inquiry into what limited objectives might be cooperatively sought by churches of differing theological convictions, and finally, open cross fire concerning some of the Church’s current and pressing problems. It was, in fact, to such “fringe benefits”—typical of every ecumenical assembly—that conference spokesmen swiftly appealed in expounding the achievements of Montreal.

But these were not objectives for which WCC had budgeted $63,000 toward the overall cost of a faith-and-order conference. What was sought was theological breakthrough. What Montreal produced was theological ambiguity transcended only by theological stalemate.

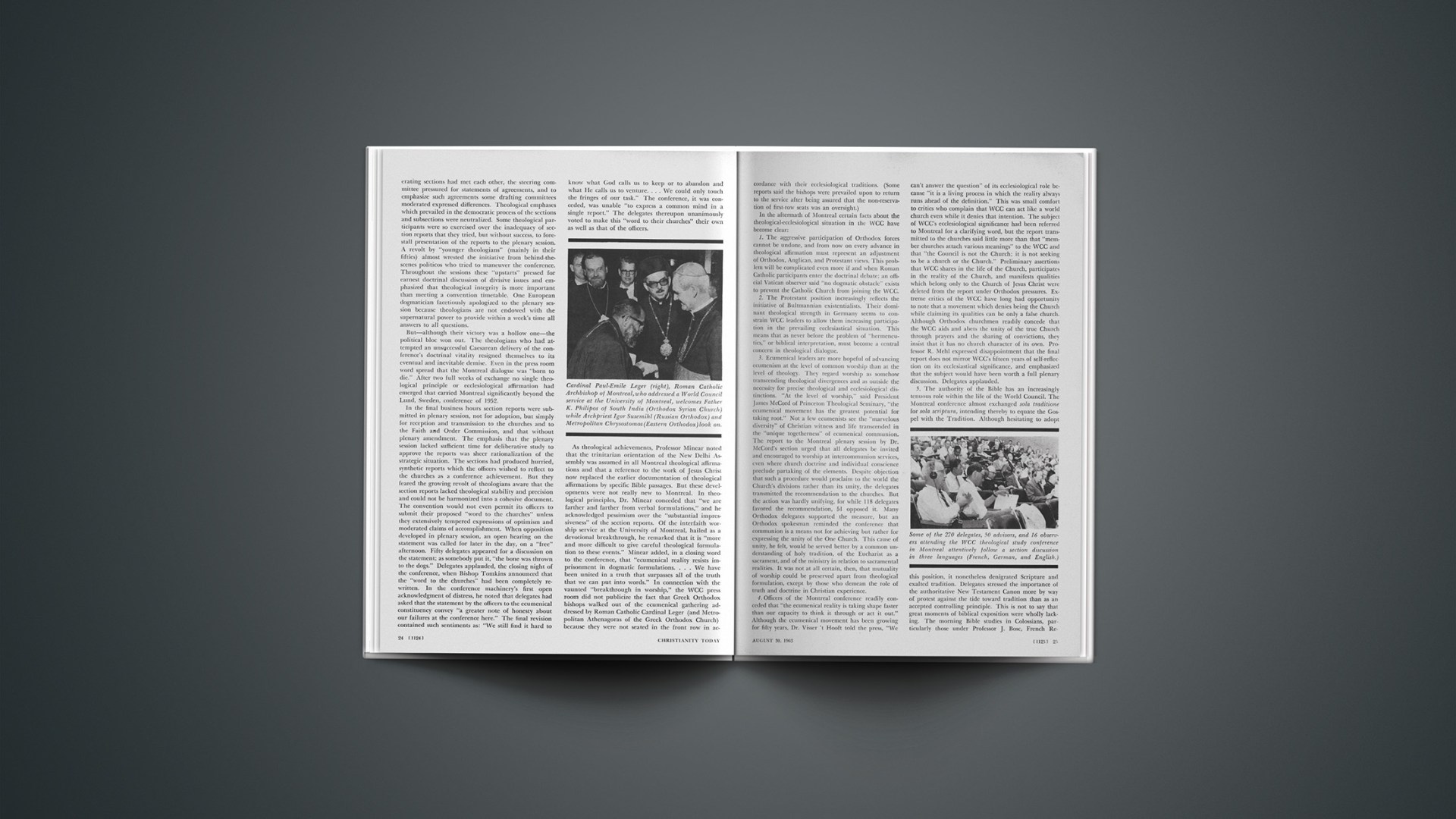

Once again, assuredly, the 350 participating delegates manifested the irreducible fact that emergence of the ecumenical movement is among the most significant developments in twentieth-century Christianity. Its admission at New Delhi of powerful Eastern Orthodox constituencies erased the dominantly pan-Protestant character of the World Council, and the larger strength of Orthodox participation was noticeable in the Montreal discussions (36 of the 270 delegates were Orthodox). Another recent trend is the warm pursuit of dialogue with Roman Catholicism in open hope of ultimate union. A major Montreal address by a Roman Catholic biblical scholar and participation of a Roman Catholic cardinal (the Archbishop of Montreal) in a public interfaith worship program further evidenced this nod to Rome. In fact, Dr. Paul S. Minear, newly elected chairman of the Faith and Order Commission, cited the inclusive Orthodox-Anglican-Protestant-Catholic service held at the University of Montreal as most noteworthy among achievements of the conference since it marked a “unity in worship deeper and wider” than that previously experienced by the participating churches.

Such developments are among what WCC’s general secretary, Dr. W. A. Visser ’t Hooft, hails as “astonishing achievements” of the movement’s brief fifty-year history in the aftermath of centuries of ecclesiastical conflict and rivalry. The fervor for unity has gained such zeal that a test vote by delegates in one of the five deliberating sections in Montreal approved by 21 to 5 the thesis that all denominations are provisional and sinful. Ecumenical staff members gave almost unanimous support.

This swift growth, Visser ’t Hooft concedes, involves serious dangers for the ecumenical movement: new enigmas arise before old ones are solved; the shortage of adequately trained personnel increases rather than lessens; need for an expanded secretariat enlarges the risk of bureaucracy; without a vast specialized organization (such as Rome’s) the movement must rely on theological faculties for much of its work. The Geneva staff is being encouraged to “borrow” professors from British universities and American seminaries in order to elevate its present “hand-to-mouth” theological existence to one of continuing competence.

But the problem of Montreal ran much deeper. For it unveiled a faith-and-order crisis not only in respect to technique—which ecumenical leaders conceded—but in respect to substance, and, moreover, reflected a power struggle within the machinery of the ecumenical movement itself.

The Geneva planners had resisted preparatory suggestions that would have preserved the study character of the Montreal conference by inviting as delegates the 120 theologians who serve on the WCC theological commission, some 80 additional theologians on working committees preparing special reports, and other qualified participants. They also declined to make the special reports prepared by these working committees the special focus of the conference. Although Montreal was promoted as a serious theological dialogue, participation was extended far beyond the range of theological competency. Almost as soon as members of the deliberating sections had met each other, the steering committee pressured for statements of agreements, and to emphasize such agreements some drafting committees moderated expressed differences. Theological emphases which prevailed in the democratic process of the sections and subsections were neutralized. Some theological participants were so exercised over the inadequacy of section reports that they tried, but without success, to forestall presentation of the reports to the plenary session. A revolt by “younger theologians” (mainly in their fifties) almost wrested the initiative from behind-the-scenes politicos who tried to maneuver the conference. Throughout the sessions these “upstarts” pressed for earnest doctrinal discussion of divisive issues and emphasized that theological integrity is more important than meeting a convention timetable. One European dogmatician facetiously apologized to the plenary session because theologians are not endowed with the supernatural power to provide within a week’s time all answers to all questions.

But—although their victory was a hollow one—the political bloc won out. The theologians who had attempted an unsuccessful Caesarean delivery of the conference’s doctrinal vitality resigned themselves to its eventual and inevitable demise. Even in the press room word spread that the Montreal dialogue was “born to die.” After two full weeks of exchange no single theological principle or ecclesiological affirmation had emerged that carried Montreal significantly beyond the Lund, Sweden, conference of 1952.

In the final business hours section reports were submitted in plenary session, not for adoption, but simply for reception and transmission to the churches and to the Faith and Order Commission, and that without plenary amendment. The emphasis that the plenary session lacked sufficient time for deliberative study to approve the reports was sheer rationalization of the strategic situation. The sections had produced hurried, synthetic reports which the officers wished to reflect to the churches as a conference achievement. But they feared the growing revolt of theologians aware that the section reports lacked theological stability and precision and could not be harmonized into a cohesive document. The convention would not even permit its officers to submit their proposed “word to the churches” unless they extensively tempered expressions of optimism and moderated claims of accomplishment. When opposition developed in plenary session, an open hearing on the statement was called for later in the day, on a “free” afternoon. Fifty delegates appeared for a discussion on the statement; as somebody put it, “the bone was thrown to the dogs.” Delegates applauded, the closing night of the conference, when Bishop Tomkins announced that the “word to the churches” had been completely rewritten. In the conference machinery’s first open acknowledgment of distress, he noted that delegates had asked that the statement by the officers to the ecumenical constituency convey “a greater note of honesty about our failures at the conference here.” The final revision contained such sentiments as: “We still find it hard to know what God calls us to keep or to abandon and what He calls us to venture.… We could only touch the fringes of our task.” The conference, it was conceded, was unable “to express a common mind in a single report.” The delegates thereupon unanimously voted to make this “word to their churches” their own as well as that of the officers.

As theological achievements, Professor Minear noted that the trinitarian orientation of the New Delhi Assembly was assumed in all Montreal theological affirmations and that a reference to the work of Jesus Christ now replaced the earlier documentation of theological affirmations by specific Bible passages. But these developments were not really new to Montreal. In theological principles, Dr. Minear conceded that “we are farther and farther from verbal formulations,” and he acknowledged pessimism over the “substantial impressiveness” of the section reports. Of the interfaith worship service at the University of Montreal, hailed as a devotional breakthrough, he remarked that it is “more and more difficult to give careful theological formulation to these events.” Minear added, in a closing word to the conference, that “ecumenical reality resists imprisonment in dogmatic formulations.… We have been united in a truth that surpasses all of the truth that we can put into words.” In connection with the vaunted “breakthrough in worship,” the WCC press room did not publicize the fact that Greek Orthodox bishops walked out of the ecumenical gathering addressed by Roman Catholic Cardinal Leger (and Metropolitan Athenagoras of the Greek Orthodox Church) because they were not seated in the front row in accordance with their ecclesiological traditions. (Some reports said the bishops were prevailed upon to return to the service after being assured that the non-reservation of first-row seats was an oversight.)

In the aftermath of Montreal certain facts about the theological-ecclesiological situation in the WCC have become clear:

1. The aggressive participation of Orthodox forces cannot be undone, and from now on every advance in theological affirmation must represent an adjustment of Orthodox, Anglican, and Protestant views. This problem will be complicated even more if and when Roman Catholic participants enter the doctrinal debate; an official Vatican observer said “no dogmatic obstacle” exists to prevent the Catholic Church from joining the WCC.

2. The Protestant position increasingly reflects the initiative of Bultmannian existentialists. Their dominant theological strength in Germany seems to constrain WCC leaders to allow them increasing participation in the prevailing ecclesiastical situation. This means that as never before the problem of “hermeneutics,” or biblical interpretation, must become a central concern in theological dialogue.

3. Ecumenical leaders are more hopeful of advancing ecumenism at the level of common worship than at the level of theology. They regard worship as somehow transcending theological divergences and as outside the necessity for precise theological and ecclesiological distinctions. “At the level of worship,” said President James McCord of Princeton Theological Seminary, “the ecumenical movement has the greatest potential for taking root.” Not a few ecumenists see the “marvelous diversity” of Christian witness and life transcended in the “unique togetherness” of ecumenical communion. The report to the Montreal plenary session by Dr. McCord’s section urged that all delegates be invited and encouraged to worship at intercommunion services, even where church doctrine and individual conscience preclude partaking of the elements. Despite objection that such a procedure would proclaim to the world the Church’s divisions rather than its unity, the delegates transmitted the recommendation to the churches. But the action was hardly unifying, for while 118 delegates favored the recommendation, 51 opposed it. Many Orthodox delegates supported the measure, but an Orthodox spokesman reminded the conference that communion is a means not for achieving but rather for expressing the unity of the One Church. This cause of unity, he felt, would be served better by a common understanding of holy tradition, of the Eucharist as a sacrament, and of the ministry in relation to sacramental realities. It was not at all certain, then, that mutuality of worship could be preserved apart from theological formulation, except by those who demean the role of truth and doctrine in Christian experience.

4. Officers of the Montreal conference readily conceded that “the ecumenical reality is taking shape faster than our capacity to think it through or act it out.” Although the ecumenical movement has been growing for fifty years, Dr. Visser ’t Hooft told the press, “We can’t answer the question” of its ecclesiological role because “it is a living process in which the reality always runs ahead of the definition.” This was small comfort to critics who complain that WCC can act like a world church even while it denies that intention. The subject of WCC’s ecclesiological significance had been referred to Montreal for a clarifying word, but the report transmitted to the churches said little more than that “member churches attach various meanings” to the WCC and that “the Council is not the Church; it is not seeking to be a church or the Church.” Preliminary assertions that WCC shares in the life of the Church, participates in the reality of the Church, and manifests qualities which belong only to the Church of Jesus Christ were deleted from the report under Orthodox pressures. Extreme critics of the WCC have long had opportunity to note that a movement which denies being the Church while claiming its qualities can be only a false church. Although Orthodox churchmen readily concede that the WCC aids and abets the unity of the true Church through prayers and the sharing of convictions, they insist that it has no church character of its own. Professor R. Mehl expressed disappointment that the final report does not mirror WCC’s fifteen years of self-reflection on its ecclesiastical significance, and emphasized that the subject would have been worth a full plenary discussion. Delegates applauded.

5. The authority of the Bible has an increasingly tenuous role within the life of the World Council. The Montreal conference almost exchanged sola traditione for sola scriptura, intending thereby to equate the Gospel with the Tradition. Although hesitating to adopt this position, it nonetheless denigrated Scripture and exalted tradition. Delegates stressed the importance of the authoritative New Testament Canon more by way of protest against the tide toward tradition than as an accepted controlling principle. This is not to say that great moments of biblical exposition were wholly lacking. The morning Bible studies in Colossians, particularly those under Professor J. Bosc, French Reformed theologian, were superb. Even in the section meetings some delegates rested their case squarely and exclusively on the biblical data. But nowhere in the dialogue was there unanimity concerning the kind of appeal that could be made to Scripture. In one session discussing ordination, a Reformed minister’s spirited appeal to the Bible was greeted approvingly by a Russian Orthodox priest, who said that he hoped the delegates would keep the New Testament criterion in mind when considering the ordination of women. Dr. Minear characterized WCC theological reports as “more biblical in spirit” although not so “lavishly sprinkled” with biblical quotations as in the past. There was an obvious effort to expound theology on a “Christological base”—urged by Barthians and Bultmannians for quite different reasons, and resisted by some Eastern Orthodox bishops who advocated a “trinitarian base” to counteract “Christological unitarianism.” Appeal to the person and work of Christ for an analogical understanding of the nature and work of the Church was responsible, in fact, for one interminable sectional controversy as to whether the ministry of the Church is an imitation or an extension of Christ’s ministry. That the Church’s ministry is a response to Christ’s ministry is beyond dispute. But an analogical appeal, apart from the higher governance of scriptural teaching, cannot discriminate correspondences from differences in the two ministries, and runs the danger therefore of compromising the unique and final work of Christ. The one-sided emphasis on the analogical implications of Christ’s ministry obviously reflects newer views of revelation which emphasize event more than propositional truths.

Facing The Ideological Conflict

The main objective of the political bloc was to achieve broad phrasing which ruled out nobody’s point of view, without adequately expressing anyone’s. In one section, for example, the phrase “the sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving” was openly acknowledged to serve the role of “highly useful ambiguity,” since it “preserves the interests of those who hold a eucharistic theology and sacerdotal ministry while not dissolving the interests of those who do not go that far.” And to say that “the Holy Spirit comes to each member in his baptism for the quickening of faith” was ambiguous enough to pacify Baptist as well as Orthodox, Anglican, Lutheran, and Reformed participants. When one delegate insisted that the phrase “the unity of baptism” could not be stretched to cover both “believer-baptism” and “infant baptism,” a French theologian pronounced the controversy unimportant (Baptist delegates disagreed), since the report elsewhere affirmed “one Lord, one baptism.” The deliberate incorporation of verbal generalities yielded a hasty production of a pseudo-ecumenical document acceptable to the conference leadership but distasteful to professional theologians, since mutual acceptability was possible only because the divergent communions gave different interpretations to identical formulas. This “shell game” approach to faith-and-order issues exasperated many a theologian.

In assessing the Montreal confrontation, Dr. Minear told the press that the “colossal combination of collisions” attested the fact that differences were not being subordinated. But many of the section tensions arose in the process of trying to achieve more doctrinally precise formulations agreeable to all, by sharpening up preliminary synthetic statements shaped in verbal generalities in an earlier atmosphere of mutual affability.

What The Theologians Want

What most theologians want is smaller study and work groups and freedom from the duress of paper production. Although they differ concerning the ideal role of faith and order in the ecumenical movement, some consensus is likely to emerge among members of the Faith and Order Commission before its 1964 meeting on Cyprus. Some are ready to dissolve faith and order as a separate enterprise, hoping thereby to disseminate its concern throughout the ecumenical movement; others hold such action might have just the opposite effect. Still others contend that since ecumenical activity is concerned with church unity, faith-and-order studies should be confined to areas of frontier conflict. A number of “younger theologians,” however, insist that doctrinal integrity is impossible apart from the entire movement’s permeation by theological concern, and they would greatly widen theological participation.

In view of Montreal developments, professional theologians were in no mood to applaud the strictures leveled at them by New York lawyer William Stringfellow, member of the Faith and Order Commission, who flew into Montreal merely long enough to picture the conference as “an academic, professionalized, esoteric, elite ecumenical monologue in which the world is seldom heard or addressed, but in which for the most part, professors, theoreticians, patriarchs, politicians, and alas, bureaucrats, talk to themselves, each other, and their vested interests in the status quo of Christendom.” Some churchmen dismissed Stringfellow’s remarks as “arrogant,” and not a few theologians resented them. In Europe, remarked one delegate, one may criticize, but one does not insult theologians.

Actually, nobody was more indignant over the paltry achievements of Montreal than the theologians themselves. The fruit of ten years’ work had been largely ignored in the deliberations. In the section on “Christ and the Ministry,” Dr. Edmund Schlink’s fine preliminary study on “Apostolic Succession” was given scarcely any consideration, yet the delegates ventured to commend it to the churches for study.

Instead of openly conceding that the cosmopolitan character of the conference was an obstacle, its leaders justified the broad participation of non-theologians on the ground that theological earnestness must be scattered throughout the whole Church (which nobody questions). Nowhere did they ask whether the Montreal exhibition might confuse rather than edify the layman. The answer to that question must now come when and if the churches study the reports transmitted to them.