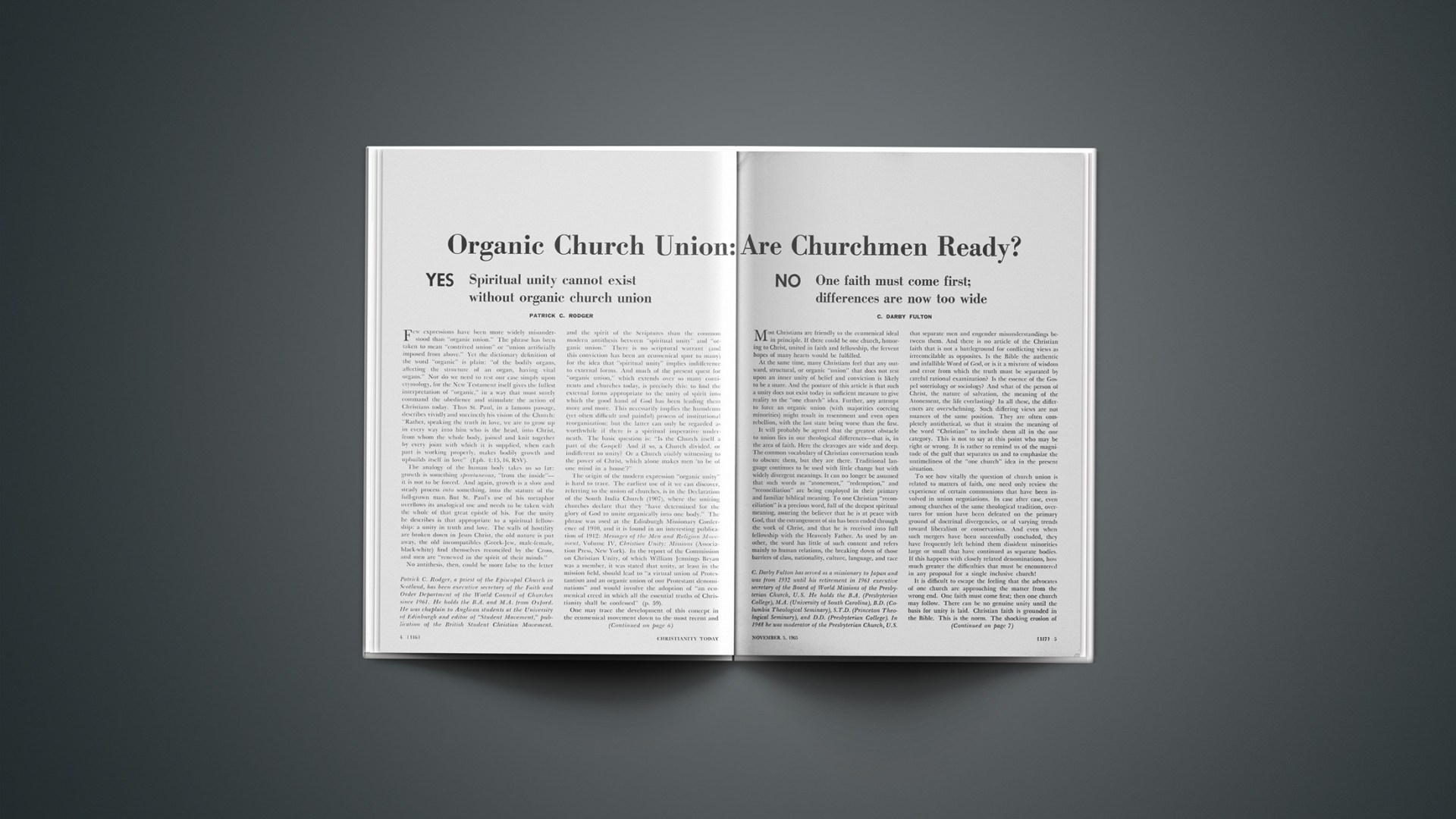

NO One faith must come first; differences are now too wide

Most Christians are friendly to the ecumenical ideal in principle. If there could be one church, honoring to Christ, united in faith and fellowship, the fervent hopes of many hearts would be fulfilled.

At the same time, many Christians feel that any outward, structural, or organic “union” that does not rest upon an inner unity of belief and conviction is likely to be a snare. And the posture of this article is that such a unity does not exist today in sufficient measure to give reality to the “one church” idea. Further, any attempt to force an organic union (With majorities coercing minorities) might result in resentment and even open rebellion, with the last state being worse than the first.

It will probably be agreed that the greatest obstacle to union lies in our theological differences—that is, in the area of faith. Here the cleavages are wide and deep. The common vocabulary of Christian conversation tends to obscure them, but they are there. Traditional language continues to be used with little change but with widely divergent meanings. It can no longer be assumed that such words as “atonement,” “redemption,” and “reconciliation” are being employed in their primary and familiar biblical meaning. To one Christian “reconciliation” is a precious word, full of the deepest spiritual meaning, assuring the believer that he is at peace with God, that the estrangement of sin has been ended through the work of Christ, and that he is received into full fellowship with the Heavenly Father. As used by another, the word has little of such content and refers mainly to human relations, the breaking down of those barriers of class, nationality, culture, language, and race that separate men and engender misunderstandings between them. And there is no article of the Christian faith that is not a battleground for conflicting views as irreconcilable as opposites. Is the Bible the authentic and infallible Word of God, or is it a mixture of wisdom and error from which the truth must be separated by careful rational examination? Is the essence of the Gospel soteriology or sociology? And what of the person of Christ, the nature of salvation, the meaning of the Atonement, the life everlasting? In all these, the differences are overwhelming. Such differing views are not nuances of the same position. They are often completely antithetical, so that it strains the meaning of the word “Christian” to include them all in the one category. This is not to say at this point who may be right or wrong. It is rather to remind us of the magnitude of the gulf that separates us and to emphasize the untimeliness of the “one church” idea in the present situation.

To see how vitally the question of church union is related to matters of faith, one need only review the experience of certain communions that have been involved in union negotiations. In case after case, even among churches of the same theological tradition, overtures for union have been defeated on the primary ground of doctrinal divergencies, or of varying trends toward liberalism or conservatism. And even when such mergers have been successfully concluded, they have frequently left behind them dissident minorities large or small that have continued as separate bodies. If this happens with closely related denominations, how much greater the difficulties that must be encountered in any proposal for a single inclusive church!

It is difficult to escape the feeling that the advocates of one church are approaching the matter from the wrong end. One faith must come first; then one church may follow. There can be no genuine unity until the basis for unity is laid. Christian faith is grounded in the Bible. This is the norm. The shocking erosion of faith, so widespread in the Church today, is the sure result when men doubt the Word of God and join the secular confusion. And this sweeps away the very foundation on which any real unity can be built. The parable of our own national life illustrates the point. Our nation is established upon the broad principles of her Constitution, which provides the basis for unity. The Constitution is the contract or agreement by which the citizens of the United States propose to order their lives as a people, and which they are sworn to uphold. Any perversion of the Constitution or any habit of disregarding its clear provisions would threaten the solidarity of the nation, and might lead to confusion and anarchy. Similarly, nothing can more easily destroy the essential fraternity and oneness in the Church than vagueness or disagreement on the cardinal principles of faith. The divisions within Protestantism are in large measure the result of doctrinal aberrations of one kind or another, whether of modernism on the one hand or of narrow obscurantism on the other. The responsibility for this disunity must be laid more at the feet of those who advocate another gospel than at the feet of those who decline to join in a retreat from biblical faith.

Most of the insistent demands for one church come from the side of theological liberalism. Ironically, this very liberalism stands as the greatest single obstacle to union, making the unity effort suspect in the eyes of those who see it as a movement of compromise or of varying shades of unbelief. Thus the question of union itself has been, and continues to be, a chief cause of strife and disunity within many denominations.

Another deterrent to “one church” is the fear of ecclesiastical power. Monopolism, whether in business, government, or religion, easily becomes the instrument of abuse. The totalitarian church is as much to be dreaded as the totalitarian state—possibly more, for the monopolistic church extends its control over the hearts and consciences of men as well as over their political structures and social institutions. Millions of people still remember the lessons of history. They cannot erase easily from their minds the record of era after era, nation after nation, in which the church became the symbol of oppression, exercising dominance over every sphere of life, subjecting even the state to its decrees, ruling the consciences of men, and destroying human freedom. Examples are many, but one will suffice. In Mexico earlier in this century, the “one church” with its totalitarian power owned three-fourths of the land, controlled the banks and the national economy, directed public education, managed elections, and virtually ran the country while it underwent moral and spiritual decline. A revolution was necessary to wrest the nation from ecclesiastical oppression and restore freedom to the people.

Although we do not have one church in our country, the dangers of concentrated power are apparent in trends that have currently made the National Council of Churches a controversial subject in many denominations. Highly significant has been the impression created that the council speaks as the voice of Protestantism. Its pronouncements on almost every conceivable subject, many of which seem only remotely related to the Church’s primary spiritual mission and message, have aroused the deep concern of thousands of evangelicals. Anyone who so desires may obtain from the central office of the NCC a list of all pronouncements, statements of policy, and resolutions issued since the council’s organization fifteen years ago. A quick glance at these will reveal the alarming extent to which they are weighted with political, economic, and social issues, and how little there is of redemptive, evangelical content. They do not differ materially from the statements of secular organizations that speak in these fields except that they bear a Christian label. Many of them seem tantamount to partisan lobbying, whether so intended or not. There is a persistent emphasis on a largely secularized Christianity that is little more than a baptized humanism, devoid of grace and spiritual power. A preoccupation with social relevance appears to have led to a serious neglect of the Gospel of faith and salvation. To this extent there has been a distortion of the Christian message. It would be tragic indeed if in seeking to make her message relevant to contemporary life the Church lost her relevance to God, to Christ, and to the salvation of men.

It is doubtful whether the National Council of Churches has made any notable contribution to the cause of real Christian unity. If its Division of Overseas Ministries may be taken as an example, it would be difficult to find one significant service that was not already being performed by the former Foreign Missions Conference of North America and other agencies of cooperation before the council came into being. Actually, the formation of the council radically reduced the number of boards and societies engaged in cooperative planning and action in their overseas ministries.

These problems, apparent enough in the case of the National Council, would be greatly intensified if there were one church. The concentration of power within a single organization always presents a temptation to overbearing authority. In the case of the Church, as experience has shown, the power is manifested in the application of pressures through lobbying and manipulation in political and public issues, and in the final suppression of individual conscience and freedom.

As long as there is liberty to exist as distinct ecclesiastical bodies in which we find a congenial spiritual adjustment, to which we can yield our full loyalty and through which we can work in happy cooperation with others of like faith in sister denominations, why should we surrender that privilege? What is to be gained? Are the unions of churches more effective in leading men to Christ? Does the spiritual birthrate rise? Does Christian liberality flourish when churches unite? Are consciences free that are forced to bend to compromise? And what reality would there be to an organic union that harbored every kind of creedal and theological disunity? How long could it possibly last?

There is no particular virtue in union itself; everything depends upon the purposes for which the union exists. There can be union in unbelief. Yet some persons seem to feel that to be divided is itself a cardinal sin. They speak of denominations as the “scandal” of Christianity. We are told that the non-Christian world is confused by our many sects, and that this hinders its acceptance of our faith. The point, we believe, has been greatly overplayed. Christianity offers nothing novel in this respect. Every religious system has similar, and even wider, divergencies. The pattern is familiar all over the world.

The real “scandal” is not in the plurality of churches. Rather, it is in the disaffections in faith and doctrine that have made divisions inevitable. Was the Protestant Reformation a mistake? Were Luther, Calvin, Huss, and Zwingli irresponsible dissidents who splintered the Church and doomed it to perpetual division? Or were they courageous voices who challenged the evils of the day and called the Church to remembrance of her true role in the Gospel?

It is not “one church” that we need, but one faith; not union, but true Christian unity. The fact is more important than the form. And it is not something that we can have merely by voting it, or by desiring it. Christian unity is more than the sentimental “togetherness” about which we hear so much today. It is more than a spirit of sanctified camaraderie, more than a cup of coffee between Sunday school and church. It is not just a collegiate exuberance such as we express when we sing, “The more we get together, the happier we will be.” It is more than a mood or attitude, more than an outflowing of good will. Christian unity rests on real substance. It has definite and objective content. It derives from certain roots of common loyalty, of common acceptance of truth, and of mutual purpose and commitment. The koinonia is not something apart from the kerygma. The fellowship is in the Gospel and its proclamation.

Here, then, is something to which the Church can aspire—not “one church,” but one mind, one spirit, one faith. Let her give herself and all her energies to the fortifying of those foundations of her unity which Paul describes in that magnificent trilogy, “One Lord, one faith, one baptism.” If she pursues these goals with all her heart and soul and mind, perhaps that other ideal of “one church” will not always elude her.