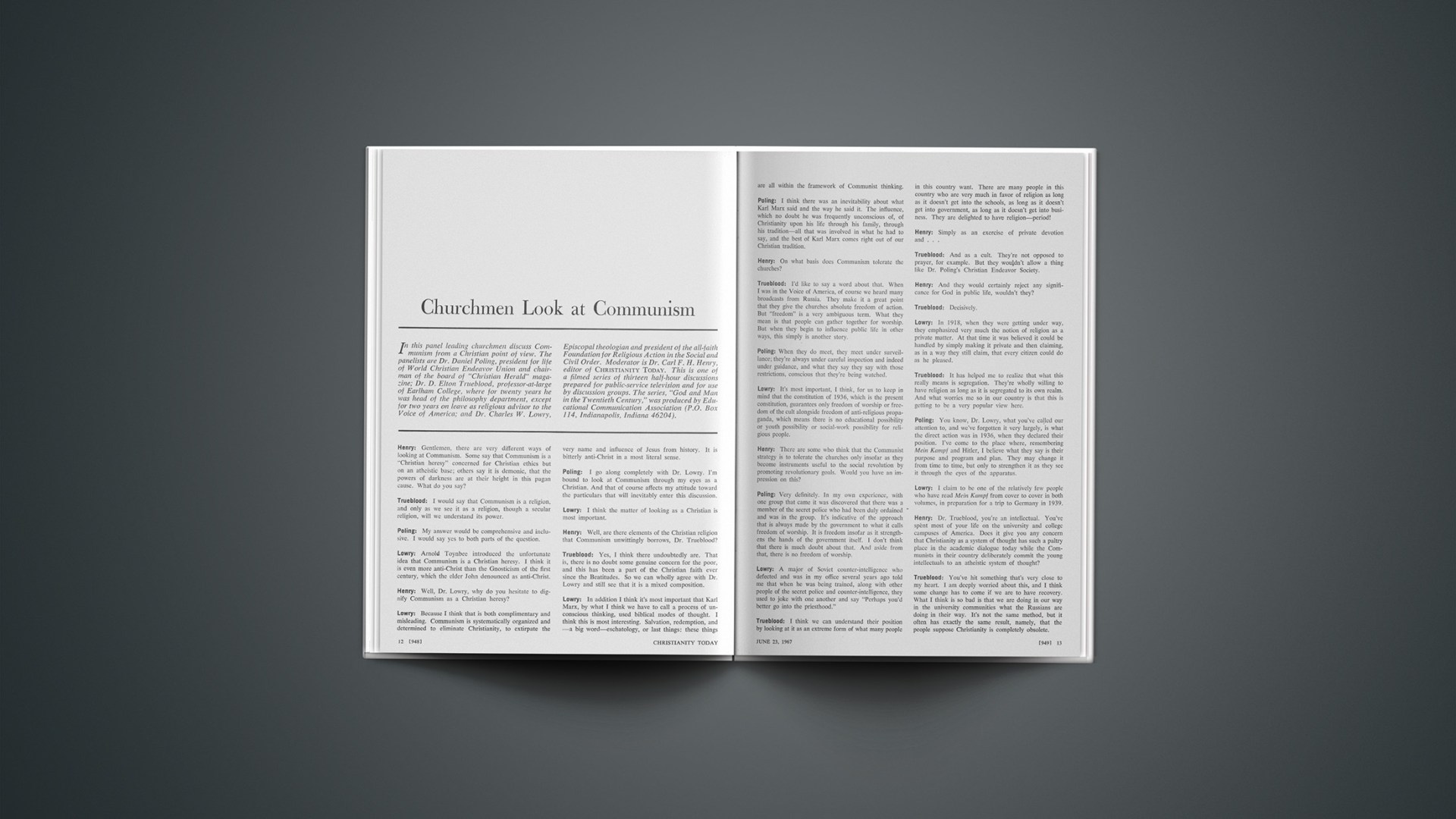

In this panel leading churchmen discuss Communism from a Christian point of view. The panelists are Dr. Daniel Poling, president for life of World Christian Endeavor Union and chairman of the board of “Christian Herald” magazine; Dr. D. Elton Trueblood, professor-at-large of Earlham College, where for twenty years he was head of the philosophy department, except for two years on leave as religious advisor to the Voice of America; and Dr. Charles W. Lowry, Episcopal theologian and president of the all-faith Foundation for Religious Action in the Social and Civil Order. Moderator is Dr. Carl F. H. Henry, editor ofCHRISTIANITY TODAY.This is one of a filmed series of thirteen half-hour discussions prepared for public-service television and for use by discussion groups. The series, “God and Man in the Twentieth Century,” was produced by Educational Communication Association (P.O. Box 114, Indianapolis, Indiana 46204).

Henry: Gentlemen, there are very different ways of looking at Communism. Some say that Communism is a “Christian heresy” concerned for Christian ethics but on an atheistic base; others say it is demonic, that the powers of darkness are at their height in this pagan cause. What do you say?

Trueblood: I would say that Communism is a religion, and only as we see it as a religion, though a secular religion, will we understand its power.

Poling: My answer would be comprehensive and inclusive. I would say yes to both parts of the question.

Lowry: Arnold Toynbee introduced the unfortunate idea that Communism is a Christian heresy. I think it is even more anti-Christ than the Gnosticism of the first century, which the elder John denounced as anti-Christ.

Henry: Well, Dr. Lowry, why do you hesitate to dignify Communism as a Christian heresy?

Lowry: Because I think that is both complimentary and misleading. Communism is systematically organized and determined to eliminate Christianity, to extirpate the very name and influence of Jesus from history. It is bitterly anti-Christ in a most literal sense.

Poling: I go along completely with Dr. Lowry. I’m bound to look at Communism through my eyes as a Christian. And that of course affects my attitude toward the particulars that will inevitably enter this discussion.

Lowry: I think the matter of looking as a Christian is most important.

Henry: Well, are there elements of the Christian religion that Communism unwittingly borrows, Dr. Trueblood?

Trueblood: Yes, I think there undoubtedly are. That is, there is no doubt some genuine concern for the poor, and this has been a part of the Christian faith ever since the Beatitudes. So we can wholly agree with Dr. Lowry and still see that it is a mixed composition.

Lowry: In addition I think it’s most important that Karl Marx, by what I think we have to call a process of unconscious thinking, used biblical modes of thought. I think this is most interesting. Salvation, redemption, and—a big word—eschatology, or last things: these things are all within the framework of Communist thinking.

Poling: I think there was an inevitability about what Karl Marx said and the way he said it. The influence, which no doubt he was frequently unconscious of, of Christianity upon his life through his family, through his tradition—all that was involved in what he had to say, and the best of Karl Marx comes right out of our Christian tradition.

Henry: On what basis does Communism tolerate the churches?

Trueblood: I’d like to say a word about that. When I was in the Voice of America, of course we heard many broadcasts from Russia. They make it a great point that they give the churches absolute freedom of action. But “freedom” is a very ambiguous term. What they mean is that people can gather together for worship. But when they begin to influence public life in other ways, this simply is another story.

Poling: When they do meet, they meet under surveillance; they’re always under careful inspection and indeed under guidance, and what they say they say with those restrictions, conscious that they’re being watched.

Lowry: It’s most important, I think, for us to keep in mind that the constitution of 1936, which is the present constitution, guarantees only freedom of worship or freedom of the cult alongside freedom of anti-religious propaganda, which means there is no educational possibility or youth possibility or social-work possibility for religious people.

Henry: There are some who think that the Communist strategy is to tolerate the churches only insofar as they become instruments useful to the social revolution by promoting revolutionary goals. Would you have an impression on this?

Poling: Very definitely. In my own experience, with one group that came it was discovered that there was a member of the secret police who had been duly ordained and was in the group. It’s indicative of the approach that is always made by the government to what it calls freedom of worship. It is freedom insofar as it strengthens the hands of the government itself. I don’t think that there is much doubt about that. And aside from that, there is no freedom of worship.

Lowry: A major of Soviet counter-intelligence who defected and was in my office several years ago told me that when he was being trained, along with other people of the secret police and counter-intelligence, they used to joke with one another and say “Perhaps you’d better go into the priesthood.”

Trueblood: I think we can understand their position by looking at it as an extreme form of what many people in this country want. There are many people in this country who are very much in favor of religion as long as it doesn’t get into the schools, as long as it doesn’t get into government, as long as it doesn’t get into business. They are delighted to have religion—period!

Henry: Simply as an exercise of private devotion and …

Trueblood: And as a cult. They’re not opposed to prayer, for example. But they wouldn’t allow a thing like Dr. Poling’s Christian Endeavor Society.

Henry: And they would certainly reject any significance for God in public life, wouldn’t they?

Trueblood: Decisively.

Lowry: In 1918, when they were getting under way, they emphasized very much the notion of religion as a private matter. At that time it was believed it could be handled by simply making it private and then claiming, as in a way they still claim, that every citizen could do as he pleased.

Trueblood: It has helped me to realize that what this really means is segregation. They’re wholly willing to have religion as long as it is segregated to its own realm. And what worries me so in our country is that this is getting to be a very popular view here.

Poling: You know, Dr. Lowry, what you’ve called our attention to, and we’ve forgotten it very largely, is what the direct action was in 1936, when they declared their position. I’ve come to the place where, remembering Mein Kampf and Hitler, I believe what they say is their purpose and program and plan. They may change it from time to time, but only to strengthen it as they see it through the eyes of the apparatus.

Lowry: I claim to be one of the relatively few people who have read Mein Kampf from cover to cover in both volumes, in preparation for a trip to Germany in 1939.

Henry: Dr. Trueblood, you’re an intellectual. You’ve spent most of your life on the university and college campuses of America. Does it give you any concern that Christianity as a system of thought has such a paltry place in the academic dialogue today while the Communists in their country deliberately commit the young intellectuals to an atheistic system of thought?

Trueblood: You’ve hit something that’s very close to my heart. I am deeply worried about this, and I think some change has to come if we are to have recovery. What I think is so bad is that we are doing in our way in the university communities what the Russians are doing in their way. It’s not the same method, but it often has exactly the same result, namely, that the people suppose Christianity is completely obsolete.

Lowry: I wonder too whether there isn’t also a tremendously grave danger in that on our campuses, among the intellectuals of America and of the world, there is, it seems to me, the notion of a kind of semi-Marxism, namely, that salvation is going to be found by man through the environment, through manipulating and changing the environment. This eclipses completely anything religion has understood by salvation.

Trueblood: Yes, Dr. Lowry, our danger is not from the avowed Communists; they are rather few. I know some of them.

Lowry: I know a few.

Trueblood: But I cannot name very many. I can name you hundreds, however, who are really giving aid and comfort to what is fundamentally the Marxist philosophy.

Poling: Dr. Trueblood, to me the most encouraging thing at this point—and this question is the most important question, it seems to me, that you’ve asked us—is the fact that millions of young people themselves are in revolt against this. Take that demonstration in London recently, when Billy Graham asked all under twenty-five years of age to indicate their presence; it seemed to me that everybody there was under twenty-five—or else that they were prevaricating.

Trueblood: You mean at Earls Court?

Poling: I mean at Earls Court. The great London campaign. And my own experience with young people today is that again and again they’re in revolt against what seems to be this academic trend in the United States, all over the country. To me it’s a great encouragement. You cannot get for this position, which you have so succinctly stated, audiences that even compare in numbers of youth with the great crowds that gather when there is a presentation of the positive and dynamic evangelical message.

Trueblood: If it is presented unapologetically. That’s the difference.

Henry: There are groups of churchmen, as you know, who have insisted that we ought to recognize Red China and that Communist China should be admitted to the United Nations. What do you think?

Poling: Well, I thank you for that question. I hoped you would ask it. And so that the figures will be accurate I brought this statement. In the summer of 1966 I was responsible for initiating a poll in which 150,000 Protestant clergymen were asked three questions: Do you favor the admission of Communist China to the United Nations? Do you favor recognition of Communist China? And do you favor accepting the condition imposed by Communist China for possible entrance to the United Nations, namely, that Free China be excluded from the United Nations? Now of the 150,000 polled—and this poll was made by a commercial organization—nearly 32,000 replied. Of the 32,000, 72.9 per cent said “no” to the admission of Red China to the United Nations, and 71.4 per cent said “no” to recognition. But on that other question, 93.7 per cent of the Protestant ministers polled said “no” to the exclusion of Free China from the United Nations.

Lowry: Dr. Poling, the return there of 32,000 is pretty good, isn’t it?

Henry: It’s a remarkable percentage.

Poling: Very remarkable. You see, it’s better than 20 per cent, and 10 per cent on a poll of that kind is considered pretty good. We said that we would keep their identities secret unless they wished to be identified—and over 12,000 said, “We wish to be identified with this.”

Henry: Do you consider the supposed cleavage between Russian Communism and Chinese Communism a hopeful sign?

Lowry: Well, there is no question, Dr. Henry, that this has had a very decisive effect on many trends and many developments. Of course, it’s still early, and we can’t tell for sure, naturally, how it’s going to come out. But the whole tendency for various regimes in Eastern Europe to take more independence, to try to reach for it—the whole idea of polycentrism, which, for example, the Italian Communists play up—is the result of this. It has had a very fundamental effect. We can’t tell, of course, what the outcome will be. It depends on whether there is ever a reconciliation, which Brezhnev and Kosygin came in to try to effect, and which is one reason Khrushchev went out.

Henry: They’re still both Communist. Ought we to make a one-and-one identification between the Western powers and Christianity? Dr. Trueblood, what would you say?

Trueblood: You simply cannot honorably make that identification. Many of the Western powers are only quasi-Christian. They do have some Christian basis in their background. The simplification is what is evil here. It is wrong to simplify by saying we’re all Christian. It is wrong to simplify by saying we are merely secular. Both of these are erroneous statements.

Henry: What is the great strength of the Western world?

Trueblood: I think the great strength is that we have these residual elements of self-discipline, of respect for the individual, of equality before the law. We don’t always demonstrate these, but they are great ideas.

Lowry: Let me say a word on that. It seems to me that we could put this by saying the power of tradition, and tradition is described, I think, by what Dr. Trueblood said. Now, in contrast, Communism is the most radical view that has ever come before mankind because it wants to drop and to destroy all tradition; only the future counts.

Poling: You know, Dr. Lowry, I think the great word in there as I listen to Dr. Trueblood and to you is opportunity—that’s what we still have.

Henry: The deliberate commitment to a free society that makes possible on an open mass-communications media like this a discussion of concerns like Christianity and Communism.

Trueblood: Now, I like this very much; but, Dr. Lowry, I’d like to challenge you on this word “radical.” I’d like to uphold the idea that the Christian conception is the most radical that the world has ever seen. This idea that every human being, whatever his color, whatever his beginnings, is one who is actually made in the image of the living God, and one for whom Christ died—I think this is the most radical idea the world has ever seen.

Henry: What is the great weakness of the Western world?

Trueblood: That we suppose these lovely things, such as equality before the law, can exist as cut flowers separated from their sustaining roots. We’ll find that they will not, that they will wither.

Lowry: I agree with that. I think we can put it perhaps even more strongly and say that unbelief and apostasy and failure to really hold and rejoice in and believe the great things that have come down to us—I think this is the tragic weakness of the West.

Poling: Of course, there’s another word that comes into this picture right now, and it’s the word “indifference”—our failure to accept dramatically, dynamically, positively, the responsibility for the maintenance of these things. We have our freedom as an inheritance from the past, but here’s our responsibility: to pass it on unimpaired, strengthened.

Trueblood: And we have a kind of indifference that is really naïve complacency. We think these things will do themselves. They won’t.

Henry: Is it a matter of life or death for the Church, for Christianity, to win the Communists?

Poling: No, in the long look, no. But so far as I’m concerned, it is for me in my time life or death. It’s one of those immediate, compulsive responsibilities, in other words. But in the long look “Jesus shall reign where’er the sun.…” In other words, we have two matters here: we have that which is immediate and we have that which is continuing, so that Christianity and the Church are not defeated however the conflict immediately results.

Lowry: Dr. Poling, I think that from the divine standpoint you’re right, of course. But looking at it from the human standpoint and the confrontation and the challenge to us as individual Christians, I’m not sure; I think there is an urgency and maybe a crisis here, an element of crisis, that we have ducked. There is a certain scandal in the fact that Christianity has not felt driven to go out and, in the power of the Spirit of God, attempt to make contact with Communists and to find the way under God and in Jesus Christ to change the climate, change the nature and configuration of the world we’re in.

Poling: Brother, do I go along with you on that!

Henry: Are there any encouraging developments, Dr. Trueblood, in the Christian confrontation of Communism?

Trueblood: No. Is that too short an answer?

Henry: Yes, say a little more.

Trueblood: On the whole, we have not really presented anything of sufficient vigor. So far as I can see, there are very few campuses where the Christian movement has anything like the power of the new left. I’m sorry to say that. But I think it’s true.

Lowry: I don’t differ in substance with that. I would say that the failure of Communism to root out Christianity in its own countries is a slightly encouraging sign. I would say also that the way in which the cold war has developed so that there is much more openness between frontiers and movement around both of the Communists and of people in touch with Communists—this gives opportunities. I think, in other words, that the opportunity is present.

Poling: Well, there are many colleges and universities where what Dr. Trueblood has said is not completely true, where you have a tremendous sweep of dynamic Christianity. I can name them one by one, and two by two, and three by three. They are not on the front pages because it’s not news. It’s commonplace, it’s what they are doing day after day and week after week.

Henry: Well, what is the real answer to Communism?

Trueblood: The real answer to Communism is a more revolutionary faith than theirs. And we have it if only we would understand it.

Lowry: It seems to me that the real answer to Communism in terms of effecting anything—of course state power has a role, and we mustn’t neglect that—but in the end something has to reach the soul of man. I believe that the key here is the Holy Spirit. If we look back, we see that the Holy Spirit and men and women in the power of this Spirit alone were able to go against all the powers of the world and of the states and nations and Caesar. I think this has somehow got to come again. Christians have got to believe that God lives, that God is God, that the Holy Spirit is with us, and find the way to reach mankind so deeply that there will be a transformation of the whole life and the whole ambiance of the world.

Poling: I think a Methodist “amen” is good here! There is just one answer, and that answer continues to be Jesus Christ. If the evangelicals of the world, those Christians who believe this, were to unite, we would see again the same revolutionary achievement that was seen in the early Church, when those disciples—a mere handful—went out with the Holy Spirit thrusting them forth to turn the world upside down. He is the answer, and his formula is today the formula: The Gospel of Jesus Christ—personal first and social always.

Trueblood: And, Dr. Poling, we’ve got a long history of this. You can see that, though I want to be realistic, I certainly don’t mean to be discouraged. We have always been a minority. We were certainly the tiniest minority in the ancient pagan world. And I believe that if we understand ourselves, our message, and our position, we can be a great power in the present pagan world.

Lowry: Dr. Trueblood, in the Old Testament the Jews believed in the little group, the residue, the remnant.

Trueblood: And they were a minority in their whole world.

Lowry: Yet by the power of these ideas and the power of God, they have transformed the whole world.

Henry: This biblical remnant is the only remnant that can be the salt of the earth. There are other remnants, and sometimes they impose their will upon the majority. But in the long run there is only one remnant that can be a preserving force in the history of the earth.

Trueblood: But it has to keep its salty character to do this, you remember.

Henry: Precisely.

Trueblood: If it loses that, it is good for nothing, do you remember that?

Lowry: If it loses its salt, its savor, too bad.

Trueblood: So mild religion isn’t worth anything.

Henry: Dr. Polling, you’ve had a lifetime in Christian Endeavor. Do you think that the young people of America are still looking for a cause?

Poling: Always they look for a cause, and always they find a cause and give themselves in dedication to the cause. That is our opportunity.

Henry: Do you feel that Christ can fill the vacuum of the collegiate and university mind?

Poling: There is only one answer: yes. He has and he does and he will.

Henry: Out in the television audience there are multitudes of lonely and solitary people who wonder how in the clash of twentieth-century events—a clash that so often takes place in the clouds above them because of its staggering comprehensiveness today and its world involvement—they can really count for anything.

Trueblood: They feel so helpless.

Henry: Now, what can we say to a person like this?

Poling: Well, all I know is, of course, my humble experience, and after all that’s my ministry, isn’t it, finally? I’ve found the answer for myself, and I present it to my family and to those I may reach—in the words of St. Paul, “I can do all things through Christ.” That’s the answer to frustration, to everything.

Lowry: I certainly agree. But I think, too, that the student of the Bible, the person who knows the Bible, knows the way that nations were on the map, and the way that God operated through the nations even beyond their own knowledge—this is just like today. I think the reader of the Bible can be very contemporary.

Henry: Dr. Trueblood, is there anything about the twentieth-century confrontation of paganism that is different from the job that the early disciples of Jesus had on their hands with the Great Commission?

Trueblood: I cannot see that there is anything different. I know that many people think there is; they say that we’ve got a whole new set of problems and therefore must have a whole new set of answers. But I believe this is completely superficial. A man can hate his wife at six hundred miles an hour just as much as he can at six miles an hour.

Henry: There is only one answer, and that is the same answer the apostles proclaimed.

Trueblood: The notion that technology changes the fundamental questions is just a very superficial philosophy.

Henry: Thank you very much, gentlemen, for an illuminating panel. The future does not belong to any ism; it belongs to the God of the ages. And in the generations to come, men will sing the praises, not of the Communist myth, but of the revelation of God in Jesus Christ. Thank you for a good hour.