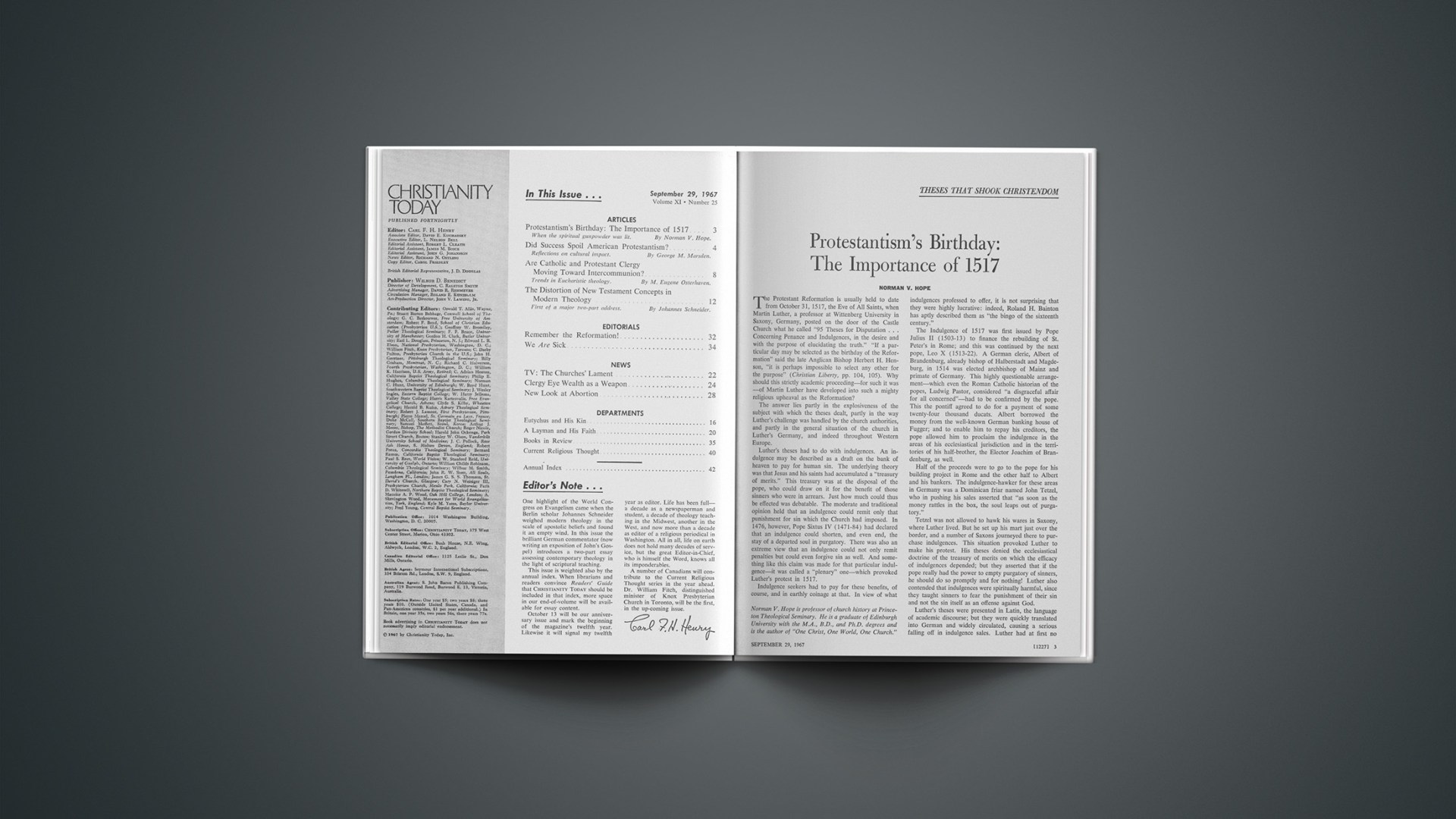

The Protestant Reformation is usually held to date from October 31, 1517, the Eve of All Saints, when Martin Luther, a professor at Wittenberg University in Saxony, Germany, posted on the door of the Castle Church what he called “95 Theses for Disputation … Concerning Penance and Indulgences, in the desire and with the purpose of elucidating the truth.” “If a particular day may be selected as the birthday of the Reformation” said the late Anglican Bishop Herbert H. Henson, “it is perhaps impossible to select any other for the purpose” (Christian Liberty, pp. 104, 105). Why should this strictly academic proceeding—for such it was—of Martin Luther have developed into such a mighty religious upheaval as the Reformation?

The answer lies partly in the explosiveness of the subject with which the theses dealt, partly in the way Luther’s challenge was handled by the church authorities, and partly in the general situation of the church in Luther’s Germany, and indeed throughout Western Europe.

Luther’s theses had to do with indulgences. An indulgence may be described as a draft on the bank of heaven to pay for human sin. The underlying theory was that Jesus and his saints had accumulated a “treasury of merits.” This treasury was at the disposal of the pope, who could draw on it for the benefit of those sinners who were in arrears. Just how much could thus be effected was debatable. The moderate and traditional opinion held that an indulgence could remit only that punishment for sin which the Church had imposed. In 1476, however, Pope Sixtus IV (1471–84) had declared that an indulgence could shorten, and even end, the stay of a departed soul in purgatory. There was also an extreme view that an indulgence could not only remit penalties but could even forgive sin as well. And something like this claim was made for that particular indulgence—it was called a “plenary” one—which provoked Luther’s protest in 1517.

Indulgence seekers had to pay for these benefits, of course, and in earthly coinage at that. In view of what indulgences professed to offer, it is not surprising that they were highly lucrative: indeed, Roland H. Bainton has aptly described them as “the bingo of the sixteenth century.”

The Indulgence of 1517 was first issued by Pope Julius II (1503–13) to finance the rebuilding of St. Peter’s in Rome; and this was continued by the next pope, Leo X (1513–22). A German cleric, Albert of Brandenburg, already bishop of Halberstadt and Magdeburg, in 1514 was elected archbishop of Mainz and primate of Germany. This highly questionable arrangement—which even the Roman Catholic historian of the popes, Ludwig Pastor, considered “a disgraceful affair for all concerned”—had to be confirmed by the pope. This the pontiff agreed to do for a payment of some twenty-four thousand ducats. Albert borrowed the money from the well-known German banking house of Fugger; and to enable him to repay his creditors, the pope allowed him to proclaim the indulgence in the areas of his ecclesiastical jurisdiction and in the territories of his half-brother, the Elector Joachim of Brandenburg, as well.

Half of the proceeds were to go to the pope for his building project in Rome and the other half to Albert and his bankers. The indulgence-hawker for these areas in Germany was a Dominican friar named John Tetzel, who in pushing his sales asserted that “as soon as the money rattles in the box, the soul leaps out of purgatory.”

Tetzel was not allowed to hawk his wares in Saxony, where Luther lived. But he set up his mart just over the border, and a number of Saxons journeyed there to purchase indulgences. This situation provoked Luther to make his protest. His theses denied the ecclesiastical doctrine of the treasury of merits on which the efficacy of indulgences depended; but they asserted that if the pope really had the power to empty purgatory of sinners, he should do so promptly and for nothing! Luther also contended that indulgences were spiritually harmful, since they taught sinners to fear the punishment of their sin and not the sin itself as an offense against God.

Luther’s theses were presented in Latin, the language of academic discourse; but they were quickly translated into German and widely circulated, causing a serious falling off in indulgence sales. Luther had at first no thought of separating himself from the Roman church. But various interviews that he had in 1518 and 1519 with representatives of the pope convinced him that the abuses against which he was protesting were not a mere excrescence of the surface of the body ecclesiastic but a cancer that was eating at its very vitals. He concluded that the papal church had departed from the New Testament doctrine of justification by grace through faith, which he believed to be the basic tenet of the Christian Gospel. And since the Church would not correct its teaching and practice on this matter, no reconciliation between it and Luther was possible. When in 1520 he was formally excommunicated by the pope, he publicly burned the papal bull of excommunication. He had passed the point of no return in his controversy with Rome.

By 1520 Luther had become the focus of widespread discontent and had acquired a following large enough to produce what has become known as “the German drama.” Patriotic Germans resented being governed by an Italian pope and sending so much hard-earned German money to Rome. They wanted a German national church governed by German bishops and independent of the papacy. Scholarly humanists applauded Luther because he appealed to the Scriptures and to Christian antiquity and not to the medieval schoolman. And many devout Christians in Germany and throughout Europe resented the all too prevalent vices of the clergy—such as cupidity and sometimes sexual irregularity—and the corruptions of the church system that they administered. Throughout his duel with the Roman church, Luther was strongly backed up by his ruler, Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, whose protection was invaluable to him both before and after his excommunication in 1520. The opposition of these various groups to the papal church had been growing in Germany for some time prior to 1517; and Luther provided it the leadership necessary to bring about the Protestant Reformation.

In the light of this account, the following statement by the late Anglican church historian Norman Sykes is an accurate explanation for why Luther’s academic protest of 1517 led to the Reformation. Said Dr. Sykes: “That [explanation] which best fits the facts is a recognition of the widespread revulsion from the Church and its system, alike in its theological and its financial expression. The old order in Germany, as in the political sphere in France in 1789, though outwardly imposing and strong, was rotten inwardly, and collapsed before the first sharp impact of revolt. Beneath the controversy about indulgences was concealed on the, religious and theological side a growing persuasion of the reality of justification by faith alone, of the impotence of the human will to work out its own salvation with fear and trembling, of the inefficiency of the system of good works and of the Treasury of Merits proclaimed and administered by the Church, and therefore ultimately a doubt of the necessity of either Church or Sacraments to salvation” (The Crisis of the Reformation, pp. 34, 35). Or as the Roman historian Leon Christiani put it, Luther “set a light to the gunpowder.”