The astonishing way in which teams of cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, anesthesiologists, and physiologists have coordinated their efforts to effect clinical heart transplants has won world attention. But almost overnight these transplants have become a subject of bristling controversy. While the only survivor of five transplant cases made good progress pending release from Groote Schuur Hospital in South Africa, debate mounted everywhere over the moral and legal implications of recent medical and technological advances.

What distinguishes heart transplants from previous homogenous transplants (including skin tissue, bone tissue, corneal tissue, and kidney transplants) is that the donor must always die before his organ can be attached to another body.

Legal questions are fully as knotty as the ethical. What, for example, are the legal proprieties if next of kin refuse to honor a deceased person’s assignment of an organ for medical purposes? What possibility exists of a black market in human hearts—might the mafia promise overnight delivery with anybody its prospective victim? What complications are posed for wills and insurance coverage if a prospective donor bequeaths his organs for transplant and invites premature death? And, since some doctors find the point of death not in heart arrest but in absence of brain function (which permits removal of organs for transplant before irreversible damage sets in), may some patients be illegally considered dead? Ought the legal determination of the moment of death to be left to the preference of the medics?

Ethical concerns are no less vexing and sometimes overlap the legal. Will it make a difference if a doctor is convinced that no providential brain restoration is ever possible? Have not some patients recovered after temporary cessation of brain function and led normal lives? Should surgeons be free to transplant human organs while the compatibility or incompatibility of body tissues is still unsure because of limited research? In view of high surgical costs, are the rich alone to benefit from clinical transplants while the poor are left to die? If one survivor is to be fashioned out of two who cannot survive independently, who dispenses the gift of life to whom? Suppose a terminal cancer victim offers to sell his heart, and the choice of recipient is to be made irrespective of purchasing power. Are specially talented persons to be preferred over Joe Ordinary? Who decides Who’s Who?

Senator Walter F. Mondale of Minnesota has pressed more than 100 doctors, theologians, philosophers, and law-school deans to face the legal and moral issues implicit not only in heart transplants but also in other recent achievements, such as an artificial virus by which scientists could eventually create and sustain laboratory life. It will probably be wiser for government to concentrate on legal concerns, without trying to legislate morality.

As long as physicians are devoted to preserving life and patients know all the facts, a given patient’s right to personal decision in good conscience ought to be fully considered. In any event, the surgeon is answerable to his professional peers for his best use of medical knowledge. To use human beings—even terminal patients with little hope of life—simply for experimental purposes would surely raise serious questions. But the voluntary risk or sacrifice in life in the high hope of benefiting others may be considered an act of courage and love. Trying to provide hope for normal life where it might otherwise remain undiscovered is no less venturesome on the operating table than in an astronaut’s space capsule whirling through the heavens. But surely, in respect to surgery, neither the patient nor the next of kin ought to be ignored in medical decisions that involve such high risks.

The argument that new discoveries specially benefit the wealthy does not carry much force. If no one could afford such operations, their larger possibilities would remain unknown; each additional case tends to lower the ultimate cost for everybody.

Brain transplanting would involve more problems than heart transplanting. According to Dr. Robert White, the famous experimentalist in animal-brain transplants, the brain of a child already contains all of what will be his or her essence as an individual—intelligence, the ability to associate ideas, personality. In view of this intimate connection between the brain and individual character, the question arises: Who survives in a brain transplant, the donor or the recipient? Insofar as psychic continuity exists, the ego remains answerable to the moral judgment of God. But since medical intervention may associate the same ego with successive bodies, what problems are posed for the biblical emphasis on bodily resurrection? It is noteworthy that virtually all body cells are said to undergo a complete change every seven years and that Christianity teaches not the absolute identity of the resurrection body with the present body but rather continuity (the Apostle Paul uses the analogy of seed and plant).

The widespread interest in clinical transplants shapes a special spiritual opportunity to confront modern man with the issues of life and death in a Christian context. What is it really to live? What accounts for the modern flight from death? Is this present lifespan really an end in itself, an absolute value divorceable from an afterlife? In view of death’s certainty, what gives life its meaning and significance?

Man’s worst ailment is one that modern theologians seem to recognize as infrequently as do philosophers, doctors, and lawyers. This is the illusion that what constitutes abundant life is temporal endurance or physical perpetuity rather than ethico-spiritual vitality. Human death is today increasingly viewed as a scientific casualty rather than as a creaturely inevitability and as a spiritual opportunity for those who have made the preparatory decisions. No doubt the root of this evasion of biblical emphases lies in a waning faith in personal immortality.

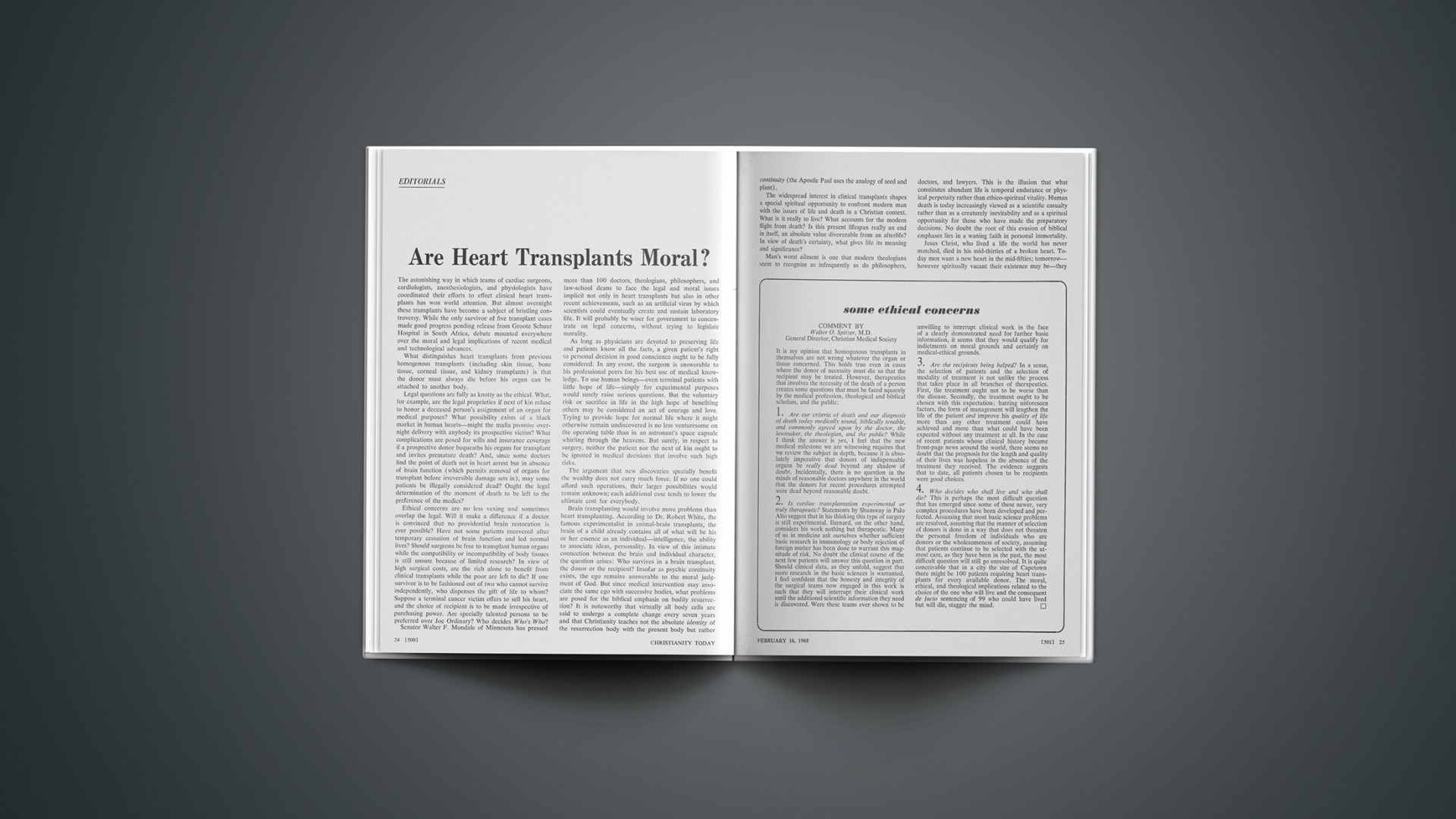

Some Ethical Concerns

COMMENT BY

Walter O. Spitzer, M.D.

General Director, Christian Medical Society

It is my opinion that homogenous transplants in themselves are not wrong whatever the organ or tissue concerned. This holds true even in cases where the donor of necessity must die so that the recipient may be treated. However, therapeutics that involves the necessity of the death of a person creates some questions that must be faced squarely by the medical profession, theological and biblical scholars, and the public:

1. Are our criteria of death and our diagnosis of death today medically sound, biblically tenable, and commonly agreed upon by the doctor, the lawmaker, the theologian, and the public? While I think the answer is yes, I feel that the new medical milestone we are witnessing requires that we review the subject in depth, because it is absolutely imperative that donors of indispensable organs be really dead beyond any shadow of doubt. Incidentally, there is no question in the minds of reasonable doctors anywhere in the world that the donors for recent procedures attempted were dead beyond reasonable doubt.

2. Is cardiac transplantation experimental or truly therapeutic? Statements by Shumway in Palo Alto suggest that in his thinking this type of surgery is still experimental. Barnard, on the other hand, considers his work nothing but therapeutic. Many of us in medicine ask ourselves whether sufficient basic research in immunology or body rejection of foreign matter has been done to warrant this magnitude of risk. No doubt the clinical course of the next few patients will answer this question in part. Should clinical data, as they unfold, suggest that more research in the basic sciences is warranted, I feel confident that the honesty and integrity of the surgical teams now engaged in this work is such that they will interrupt their clinical work until the additional scientific information they need is discovered. Were these teams ever shown to be unwilling to interrupt clinical work in the face of a clearly demonstrated need for further basic information, it seems that they would qualify for indictments on moral grounds and certainly on medical-ethical grounds.

3. Are the recipients being helped? In a sense, the selection of patients and the selection of modality of treatment is not unlike the process that takes place in all branches of therapeutics. First, the treatment ought not to be worse than the disease. Secondly, the treatment ought to be chosen with this expectation: barring unforeseen factors, the form of management will lengthen the life of the patient and improve his quality of life more than any other treatment could have achieved and more than what could have been expected without any treatment at all. In the case of recent patients whose clinical history became front-page news around the world, there seems no doubt that the prognosis for the length and quality of their lives was hopeless in the absence of the treatment they received. The evidence suggests that to date, all patients chosen to be recipients were good choices.

4. Who decides who shall live and who shall die? This is perhaps the most difficult question that has emerged since some of these newer, very complex procedures have been developed and perfected. Assuming that most basic science problems are resolved, assuming that the manner of selection of donors is done in a way that does not threaten the personal freedom of individuals who are donors or the wholesomeness of society, assuming that patients continue to be selected with the utmost care, as they have been in the past, the most difficult question will still go unresolved. It is quite conceivable that in a city the size of Capetown there might be 100 patients requiring heart transplants for every available donor. The moral, ethical, and theological implications related to the choice of the one who will live and the consequent de facto sentencing of 99 who could have lived but will die, stagger the mind.

Jesus Christ, who lived a life the world has never matched, died in his mid-thirties of a broken heart. Today men want a new heart in the mid-fifties; tomorrow—however spiritually vacant their existence may be—they may want one in the mid-eighties, for more of the same. But the human body is not fashioned to last forever—at least, not in its pre-resurrection form. Man’s “threescore years and ten” may be lengthened a decade or even two, but sooner or later not one but virtually all organs will falter and give out. Is it a service to give a thirty-year-old mind to a man with a sixty-year-old body, or a thirty-year-old body to a man with a sixty-year-old mind? Man’s hope that science may offer temporal immortality, by perpetual replacement of outworn organs, may in fact spring from a perverse rejection of his creaturehood and an aspiration to man-made eternity.

The haunting question, to be addressed to those whose present existence is really a living death, is: What do you want a new heart for?

How many heart afflictions and how many spiritual crises does modern man need before he hears and understands the Great Physician’s offer: “Cast away from you all the transgressions which you have committed against me, and get yourselves a new heart and a new spirit! Why will you die?” “A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you and I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my spirit within you, and cause you to walk in my statutes and be careful to observe my ordinances” (Ezek. 18:31; 36:26 f.).

Americans are awakening to the realization that 1968 may bring the most severe racial crisis in the nation’s history. They no longer harbor the optimistic illusion that the violence of the past four summers is a transitory nightmare that will soon vanish in the sunlight of racial concord. In view of the volatile mood present in the Negro community, many are girding themselves for the worst year yet. A hundred or more cities are developing crash programs to head off or cope with any riots that may erupt this spring and summer. The Department of Justice is conducting four weeks of meetings for 122 mayors and police chiefs on how to nip a riot in the bud. But more important, the citizenry is increasingly coming to face the fact that the Negro Revolution will not end until sound and lasting solutions are found that will bring the burgeoning Negro population into the mainstream of American life.

The gravity of our current situation may be seen in plans under way in militant groups. Dr. Martin Luther King is presently organizing a mammoth “camp-in” protest for Washington, D. C., around April 1 with a built-in threat of possible civil disobedience. Stokely Carmichael, back from his “clenched fist” tour abroad, is using the “velvet glove” to rally a united front of civil-rights groups in order to press for immediate concessions; this could precipitate violent black-power flare-ups. Radical leaders of fused anti-war and civil-rights protest movements are claiming that some two hundred thousand demonstrators may be marshaled to disrupt the Democratic Convention in Chicago in August. Deep-seated discontent in countless Negro ghettos coupled with bitter backlash feelings, especially among many blue-collar whites, could with the least provocation this summer explode into street wars in scores of urban centers. The outlook for 1968 is grim.

The complexity of the racial problem—economically, socially, politically, culturally, and spiritually—makes any solution we might here briefly propose seem simplistic and naïve. Yet we believe there are certain factors that responsible Americans of all races—and especially all Christians—must personally recognize if we are to hammer out sound solutions that will bring racial harmony and a more equitable status for Negroes in America.

1. Legitimate grievances that underlie Negro discontent must be speedily remedied. Latent feelings of superiority and hostility toward Negroes have made many white people insensitive to the disadvantages stacked against the Negro in America. The Negro has arisen within a culture of servility that has not offered the motivation for self-betterment found in other minority groups. His color has closed off opportunities open to people of other races. Whites have held his cultural patterns in low esteem, thereby impeding his absorption into national life. His enforced separation from the American mainstream has compounded a continuing vicious cycle of widespread unemployment, low standard of living, unstable home life, inadequate motivation, educational underdevelopment, and further economic instability. Many determined and hard-working Negroes have overcome these disadvantages and arisen to middle-class status. Twenty-eight per cent of non-white families now earn more than $7,000 per year—twice the percentage in 1960. But the Negro community as a whole occupies a low position on our national totem pole.

Whether the bigotry of many in the white community or the apathy of many Negroes is mainly to blame for the Negro’s plight, Americans cannot close their eyes to the facts of our present situation. The rates of broken homes, crime, illegitimate births, and juvenile delinquency are significantly higher among Negroes than among whites. In our ten worst slums, one in three Negroes cannot find work or is not earning enough to subsist on. The national Negro unemployment figure now hovers just below 10 per cent. Observation of almost any Negro-populated area will convince anyone that ghetto housing is overcrowded and decidedly sub-par. Schools in these communities fall below standards in other areas, partly because many qualified teachers refuse to accept admittedly difficult assignments there. The Christian church in most Negro communities is a culture-bound, emotionally euphoric fellowship where little solid instruction in biblical truth is communicated.

As long as these distressing conditions exist on a large scale, the Negro revolt will continue to smolder and occasionally burst into riotous flames. It will do little good for whites to assume that militant black power fanatics are totally responsible for Negro unrest and concentrate only on stopping them rather than dealing constructively with the soil of discontent where seeds of violence have sprouted. Rather Americans must exercise wisdom and patience in devising practical programs to upgrade the economic, social, and educational resources of Negroes.

If government agencies are not to widen their already burdensome commitments, the private sector of the economy must increase its efforts to provide more jobs, develop vocational training, grant home loans, and give Negroes greater hope for success in American life. Public-spirited corporations might well follow the example of the Eastman Kodak Company of Rochester, New York, which has instituted a non-discriminatory program of basic education and job training to help many mired in the “failure syndrome” to qualify for employment. Since last fall 152 people have been involved in this successful effort. This type of program could spread if Christian church members in strategic business positions would spearhead its development in their local enterprises.

Further progress would be made if Christian ministers and laymen in white churches would develop closer personal ties with Negro churches to promote understanding, encourage mutual aid, and devise cooperative witness programs to bring the message of Christ effectively to the black community. The real needs that make the Negro cry out in anxiety, in resentment, in hatred, must be seen for what they are by white people and, in cooperation with Negro leaders, dealt with positively and swiftly. Sober analysis of conditions in society must be followed by creative, humane solutions.

2. All citizens must examine their attitudes toward other races and consciously attempt to rid themselves of racial bigotry. It is commonplace to say that every person knows in his heart that he has no valid basis for hating another man merely because his skin is a different color from his own. Yet all of us in differing degrees are guilty of harboring animosity toward people of other races. Prejudice gained from our backgrounds and from generalizations based on isolated experiences must be brought to light by all men—including the most devout Christians. Although many whites would refrain from calling a Negro a “jig” or many Negroes from calling a white person a “honky,” latent antipathies exist that must be rooted out.

Racial bigotry is a sin against God and man. All men are entitled to be considered of worth because God created man in his own image and placed so high a value on him that he sent his Son, Jesus Christ, to redeem him. Unless blacks and whites accord each other mutual respect, there can never be racial harmony in our nation. The hate that erupts in violence in the streets must be seen as evidence of the hate that exists in the privacy of the heart. If men will analyze their attitudes and recognize their own conscious or submerged racial prejudices, they then can begin to rid themselves of the bitter spring from which flows the pollution of social injustices and destructive action. God can remove hatred from a man’s heart. Those who call upon the God of love to obtain love for human beings created in God’s image will find a new power to love through Jesus Christ.

3. Negroes must decisively repudiate leaders who incite hatred and violence and instead work to better their status through democratic processes. Nothing can deter Negro advancement more than anarchy in the streets that leads to bloodshed and conflagration. America is in no mood to tolerate riots. This was aptly shown by the thunderous applause that greeted President Johnson’s statement in his recent State of the Union message that “the American people have had enough of rising crime and lawlessness in this country.” Negro intellectual Bayard Rustin correctly interpreted the reaction as an expression of opposition to ghetto rioting as well as to individual criminal acts. If the Negro community does not show the maturity to disavow the violent tactics of the Stokely Carmichaels, Rap Browns, and Ron Karengas—and possibly even the Martin Luther Kings, if they open the door to civil disobedience—it not only will antagonize many whites whose consciences have been pricked by the Negro’s plight but also will show it has not accepted the spirit of our society in which Negroes seek a greater role. The majority of Negro Americans, who are by no means “Uncle Toms,” oppose violence and believe in democracy fully as much as the majority of white Americans. These responsible Negroes must courageously oppose any “soul brothers” who impede Negro betterment through hatred and the use of force.

The victories of mayoral candidates Richard Hatcher in Gary, Indiana, and Carl Stokes in Cleveland, Ohio, are proof that black power at the ballot box can elect candidates preferred by the Negro community. The “Burn, Baby, Burn,” of violent black-power mongers must give way to the “Learn, Baby, Learn” and “Earn, Baby, Earn” of legitimate black power gained through political, economic, and personal means. Repudiation of radical movements in favor of democratic measures will do much to increase respect for Negroes among whites. Likewise, Negro respect for whites will be enhanced by their rejection of white backlash policies in favor of prudence and patience.

President Johnson has said that the challenges confronting Americans at home and abroad are a test of our national will. The racial crisis looming in 1968 is such a test. Are we as a people determined to work at solving the problems in our society that impede every man’s progress? Are we willing to sacrifice to help our fellow citizens who are unable to lift themselves by their own bootstraps? Are we willing to discard our prejudices and begin to love human beings of another color personally and earnestly? Do we have the will to maintain a continuing program to elevate deserving Negro citizens despite possible unruly outbursts by a radical minority within a minority race? Our attitudes and actions as a people in 1968 will reveal whether we have the heart and will to deal constructively with this critical problem. May God help us to do so.

ALL THE KING’S HORSES

North Korea’s seizure of the American spy ship “Pueblo” threatened to flare quickly into another major international crisis. The outcome seemed to hinge on whether the eighty-three crew members would be quickly released or exchanged rather than treated as war prisoners. Few Americans, assuredly, saw in the blatant piracy of the “Pueblo” a sufficient basis for renewing the Korean War, but Senator Mike Mansfield was almost alone in his incredible suggestion that the United States should avert war by falsely asserting, if necessary, that the “Pueblo” was in North Korean waters. South Korea was also agitated, and rightly so, by Communist disregard of her national borders and attempts to murder her political leaders.

The Korean incident disclosed anew some weaknesses of American foreign policy. For several decades the United States has declared itself the leading world power. Just what this means one is increasingly at a loss to know.

American policy undercut General MacArthur’s goal of decisive victory in Korea and settled for permanent division of that nation. American policy accommodated the Berlin wall and a divided city. American policy espoused not military victory but hesitant escalation against North Vietnamese aggression. Did indecisiveness also indirectly encourage the piracy of the “Pueblo” in international waters?

The basic question for Americans was not whether to respond to the “Pueblo” outrage by hijacking a North Korean vessel, blockading the port of Wonsan, seizing the “Pueblo” by force, destroying the ship and its surroundings, or retaliating in some other way at another time and place. The question was, rather, why no rescue effort had been prearranged for such an obviously hazardous mission. Why was no action taken during almost two hours of tension before the North Koreans boarded the “Pueblo”?

If an effective foreign policy is not indirectly to encourage injustice, it must provide effective restraint and swift reprisal. In the absence of this, we can see why America’s allies are increasingly uneasy over inhibited fulfillment of our treaty commitments. We can see also why American criticism mounts over conduct of the Viet Nam war.

But we wish the doves would stipulate precisely where if anywhere they would draw a line against Communist aggression and terror. Unless Americans are ready to accept takeovers by totalitarian Communism, military withdrawal is no option. Premier Kosygin of the U.S.S.R. frankly told the editors of Life magazine that North Viet Nam “is a country with whom we are fighting for the ideas and ideals of socialism and Communism.” But neither is military demolition the answer. The humanization of man remains the Church’s urgent world task.

Much of the surviving stability of the modern world vanished when the great colonial empires of Britain, Holland, and Belgium were undermined. American liberal intellectuals energetically exaggerated the vices of colonialism while ignoring its contribution in preserving order and respect of law, providing schools, hospitals, and highways, and opening remote lands to Western technology and world trade. Their one-sided emphasis on the ideal of national self-determination soon showed its weaknesses. Unpreparedness for self-government vexed many younger nations. Worse yet, Red China and some smaller Communist protégé nations considered themselves beyond the judgment of international law and world opinion. Such newly independent nations are disposed to disregard territorial rights and to engage in international thuggery.

In recent decades American diplomacy, after urging decolonization, has tried to advance world order on its own principles. But its policy of stalemating aggression rather than reversing it has hardly proved successful. Another generation may again consider a modified benevolent colonialism preferable to a devouring nonbenevolent noncolonialism, unless collective security—the U.N. included—shows itself more effective than it has been in Viet Nam and the Middle East.

The alternative to stalemating cannot, assuredly, be annihilation of an announced enemy by the irresponsible use of total power, nor an advance abandonment of conventional for nonconventional weapons. But some alternative there needs to be to restrain aggression swiftly and retaliate injustice. The United States seems not yet to have found it. Instead, U. S. policy seems determined not to offend an announced enemy, even at high cost to American lives and domestic stability. A just cause is worthy of more than a stalemate. No nation given over to injustice has ever been worse for defeat—modern Germany and Japan included. The United States ought to get with it, or to get out of it.

EARTHA KITT’S WHITE HOUSE SPECTACLE

Vocalist Eartha Kitt’s anti-war outburst was a deed that in dozens of countries could have landed her in prison. Her impudence at a White House luncheon did more than question the President’s judgment; by indirection she said that he does not have the country’s best interests at heart. A John Bircher who called a former president a Communist rightly lost the nation’s sympathies, and Miss Kitt’s remarks deserve no better response.

Miss Kitt is entitled to her opinion, even if it is wrong. What is regrettable is that she chose to give public visibility to that opinion by taking advantage of a privilege.

Regrettably, in equally bad taste, a Williamsburg clergyman took advantage of President Johnson’s attendance at a worship service to challenge publicly the President’s conduct of the war in Viet Nam.

What the pulpit blesses the public may soon practice—and in this case, for the worse. Rudeness of this kind is no methodology by which to advance social justice.