Should a Christian ever be unhappy? In some periods of church history it would have seemed absurd to ask such a question. These were the periods in which Christians cultivated an air of grave solemnity and earned for themselves a reputation for being glum and lugubrious.

At other times—including, I think, our own day—the opposite tendency has been apparent. Evangelism has been debased into the simple invitation to “come to Jesus and be happy.” The signature tune of the Christian Church has been “I Am Happy.” Christians are to appear hearty, ebullient, and boisterous. In a Christian magazine I receive, every Christian’s picture (and there are many) shows him with a grin from ear to ear. Some Christians would defend this attitude by quoting such Scripture as “Rejoice in the Lord always.”

But the true biblical image of the Christian is neither of these. Nor is it both together, though joy and sorrow are both part of the Christian life. “There is a time to laugh, and there is a time to weep,” said the Preacher in Ecclesiastes. Moreover, we are followers of One who went about saying, “Be of good cheer.… Go in peace,” yet was called “the Man of sorrows.” The Apostle Paul expressed the same paradox in Second Corinthians 6:10—“as sorrowful, yet always rejoicing.”

Human life itself can be full of joy; God has “given us all things richly to enjoy.” That the Christian life, in particular, is intended to be joyful is obvious from Scripture and hardly needs to be emphasized.

The Gospel is “glad tidings of great joy,” and in God’s presence is “fullness of joy” (Ps. 16:11). Jesus said he wanted his disciples’ joy to be full (John 15:11; 16:24; 17:13). Both joy and peace are the fruit of the Spirit, and the Apostle Paul prayed that God would fill his people with all joy and peace in believing (see Rom. 14:17; 15:13).

I do not deny any of this. On the contrary, I believe it and rejoice in it. I see it in others and have experienced it myself. There is joy—true, deep, and lasting—in the knowledge of forgiveness and the experience of fellowship, in hearing and receiving the Word of God, in seeing a sinner repent, and in God himself, who satisfies the hungry with good things.

Dr. W. E. Sangster writes in one of his books of Dr. Farmer, the organist at Harrow, who pleaded with a Salvationist drummer not to hit the drum so hard. The beaming bandsman replies: “Lor’ bless you sir, since I’ve been converted I’m so happy I could bust the bloomin’ drum.” Thank God for this; it is an authentic Christian experience.

If we want to redress the balance in our own unbalanced days, however, I find myself wishing there were fewer grins and more tears, less laughter and more weeping. If Psalm 100 tells us to “serve the Lord with gladness,” the Apostle Paul could describe his own ministry (which must have been full of joy in many ways) as “serving the Lord with all humility and with many tears.”

Why and when should a Christian weep?

In the first place, Christians are subject to what might be called “tears of nature,” that is, the tears of natural sorrow. These are not specifically Christian tears, simply human tears. They are due to the common nature we share with all humanity, and are a response to some sorrow.

For example, there is the sorrow of parting, such as Timothy felt when Paul was arrested and taken away from him and he could not restrain his tears (2 Tim. 1:4), or such as the Ephesian elders felt when Paul said goodbye to them for the last time and they wept (Acts 20:37).

There is the sorrow of bereavement, as when Jesus cried at the graveside of Lazarus (John 11:35).

There is the sorrow of our own mortality when we sense the frailty of our body and groan, longing to be finally delivered (Rom. 8:22, 23; 2 Cor. 5:2).

There are also the many trials we undergo in life, as a result of which we are “in heaviness” (1 Pet. 1:6). This kind of experience prompted the Psalmist to pray, “Put thou my tears in thy bottle” (Ps. 56:8).

Many times I have been on a railway platform when missionaries were being seen off to the field, and many times I have attended the funeral of a Christian. On such occasions I have sensed the inhibitions of Christians who have either forced themselves to suppress their feelings or turned away to hide their tears.

There is, of course, a selfish and unrestrained weeping that would be unbecoming in Christian people. Thus we are forbidden to sorrow over our Christian dead as those who have no hope (1 Thess. 4:13). But we are not forbidden to sorrow or to weep. Indeed, it would be unnatural not to. To regard natural sorrow as unmanly is more stoic than Christian. The Gospel does not rob us of our humanity.

In addition to these various kinds of “tears of nature,” Christians are subject also to the “tears of grace.” These are tears we do not share with non-Christian people, tears which (if we shed them) God himself has caused us to shed. There are at least three forms.

1. Tears of penitence. We all know the story of the woman who stood behind Jesus weeping and began to wet his feet with her tears. These were tears of penitence for her sin and of gratitude for her forgiveness.

“But,” an impatient Christian may object, “she was a fallen woman, and these were the tears of her conversion. Certainly I am glad when eyes are moist at the gospel invitation and the penitent bench is wet with tears. This is holy water indeed. But surely Christians do not weep over their sins.”

Don’t they? I would to God they did! Have the people of God no sins to mourn and confess? Was Ezra wrong to pray and to make confession, weeping and casting himself down before the house of God? And were God’s covenant people wrong to join him in bitter weeping (Ezra 10:1)? Did Jesus not mean what he said in the Sermon on the Mount when he pronounced “blessed” those who mourn, which in the context seems to imply a mourning over their sin? Was Paul wrong as a Christian to cry, “Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” (Rom. 7:24). I know that this has often been interpreted as the cry of either an unbeliever or a defeated Christian, but from Scripture and experience I am convinced that it is the cry of a mature Christian, of one who sees the continuing corruption of his fallen nature, mourns over it, and longs for the final deliverance that death and resurrection will bring him. It is a form of that “godly sorrow” of Christian penitence about which Paul writes in Second Corinthians 7.

David Brainerd, that most saintly missionary to the American Indians at the beginning of the eighteenth century, supplies a good illustration of this kind of penitential sorrow. For example, he writes in his diary for October 18, 1740: “In my morning devotions my soul was exceedingly melted, and bitterly mourned over my exceeding sinfulness and vileness. I never before had felt so pungent and deep a sense of the odious nature of sin as at this time. My soul was then unusually carried forth in love to God and had a lively sense of God’s love to me.”

2. Tears of compassion. Tears of compassion are wept by Christian people who obey the apostolic injunction not only to “rejoice with those who rejoice” but to “weep with those who weep” (Rom. 12:15).

Of course, the non-Christian humanist can also weep tears of compassion. Indeed, some secular humanists weep tears more bitter and more copious than ours in their sorrow over the horrors and cruelties of the Viet Nam war, over starvation in Biafra, over poverty, unemployment, oppression, and racial discrimination. Are such humanists, then, more sensitive than Christian people? Are we so insulated from the sufferings of the world that we do not feel them and cannot weep over them?

But specifically Christian tears of compassion are shed over the unbelieving and impenitent, over those who (whether through blindness or willfulness) reject the Gospel, over their self-destructive folly and their grave danger.

Thus Jeremiah could cry: “O that my head were waters and my eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the slain of the daughters of my people” (Jer. 9:1; cf. 13:17 and 14:17).

Thus too Jesus Christ wept over the city of Jerusalem because it did not know the time of its visitation and was about to bring upon itself the judgment of God (Luke 19:41).

Thus too the Apostle Paul, during three years of ministry in Ephesus, did not cease night and day to admonish everyone with tears (Acts 20:31). And he could write also that he had a “great sorrow and unceasing anguish” in his heart on behalf of his Jewish kinsmen (Rom. 9:2).

Many more modern examples could be given of these Christian tears of compassion. Bishop J. C. Ryle has written of George Whitefield that the people “could not hate the man who wept so much over their souls.” Andrew Bonar wrote in his diary on his forty-ninth birthday: “Felt in the evening most bitter grief over the apathy of the district. They are perishing, they are perishing, and yet they will not consider. I lay awake thinking over it, and crying to the Lord in broken groans.” Similarly, Dr. Dale of Birmingham, who was at first critical of D. L. Moody, changed his opinion when he went to hear him. Thereafter he had the profoundest respect for him because Moody “could never speak of a lost soul without tears in his eyes.”

How can we see the increasing apostasy and demoralization of the Western world today and not burst into tears?

3. Tears of jealousy. I am referring here to the divine jealousy, which Christian people should share. Such “jealousy” is a strong zeal for the name, honor, and glory of God. It was this that caused the Psalmist to say: “My eyes shed streams of tears because men do not keep thy law” (Ps. 119:136). And it was this that led Paul to write to the Philippians of the many, whom he could mention only “with tears,” who were “enemies of the cross of Christ” (Phil. 3:18).

Here were men so concerned about the law of God and the cross of Christ that they could not bear to see them trampled under foot. Those who made themselves enemies of God’s law by violating it and of Christ’s cross by preaching another gospel brought tears to the eyes of godly people who cared. No purer tears than these are ever shed. They contain no selfishness or vanity. They show the sorrow of a human being who loves God more than anything else in the world, and who cannot see God’s love rebuffed or his truth rejected without weeping. How is it that we can walk through the secular cities of our day and restrain our tears?

In the light of this biblical evidence about the tears both of nature and of grace, I believe that we should laugh less and cry more, that if we were more Christian we should certainly be more sorrowful. We must reject that form of Christian teaching which represents the Christian life as all smiles and no tears.

Professor James Atkinson was speaking three years ago to a meeting of the Church of England Evangelical Council in London. He was describing some of the pathetically untheological conditions of the Church of England, and he did so in such a way as to make us laugh. He immediately commented: “The difference between you and me is that you laugh and I cry. Erasmus called for more Flemish wine, with no water added. Luther cried all night.”

The fundamental error underlying our modern tearlessness is a misunderstanding of God’s plan of salvation, a false assumption that his saving work is finished, that its benefits may be enjoyed completely, and that there is no need for any more sickness, suffering, or sin, which are the causes of sorrow.

This is just not true. God’s saving work is not yet done. Christian people are only half saved. True, Christ cried in triumph “It is finished,” and by his death and resurrection he completed the work he came to do. But the fruits of this salvation have not yet been fully garnered. And they will not be, and cannot be, until the end comes when Christ returns in power and glory. The ravages of the Fall have not yet been eradicated either in the world or in Christian people. We still have a fallen nature, an ingrained corruption, over which to weep. We still live in a fallen world, full of sorrow because full of suffering and sin.

Can we not see these things? The eyes that do not weep are blind eyes—eyes closed to the facts of sin and of suffering in ourselves and in the rest of humanity. To close our eyes thus is to withdraw from the world of reality, to live in Cloud Cuckoo Land, to pretend that the final victory has been won when it has not.

Thank God the day is coming when there will be no more crying, when sorrow and sighing will flee away and God will wipe away all tears from our eyes. This will take place when the kingdom of God has been consummated, when there is a new heaven and a new earth, when God’s people have been totally redeemed with new and glorified bodies, when there is no more sin and no more death.

In our lives as Christians, let us rejoice in that measure of victory already gained by Christ and received by us—in the forgiveness of our sins, in Christian fellowship, and in the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. Let us rejoice too “in hope of the glory of God” (see Rom. 5:2; 12:12; 1 Pet. 1:5–8). The expectation of God’s final victory is another source of joy. We know that those who sow in tears shall reap in joy.

And let us remember that meanwhile we are living in the interim period, between the beginning and the end of the salvation of God, between the inauguration and the consummation of victory. We are living between D Day and V Day—a period during which much blood was spilled and many tears were shed. Sin, suffering, and sorrow continue. Christian people are caught in the tension between what is and what shall be.

And so, although we are in heaviness through many temptations, we rejoice in the final victory of God. We are sorrowful, yet always rejoicing.

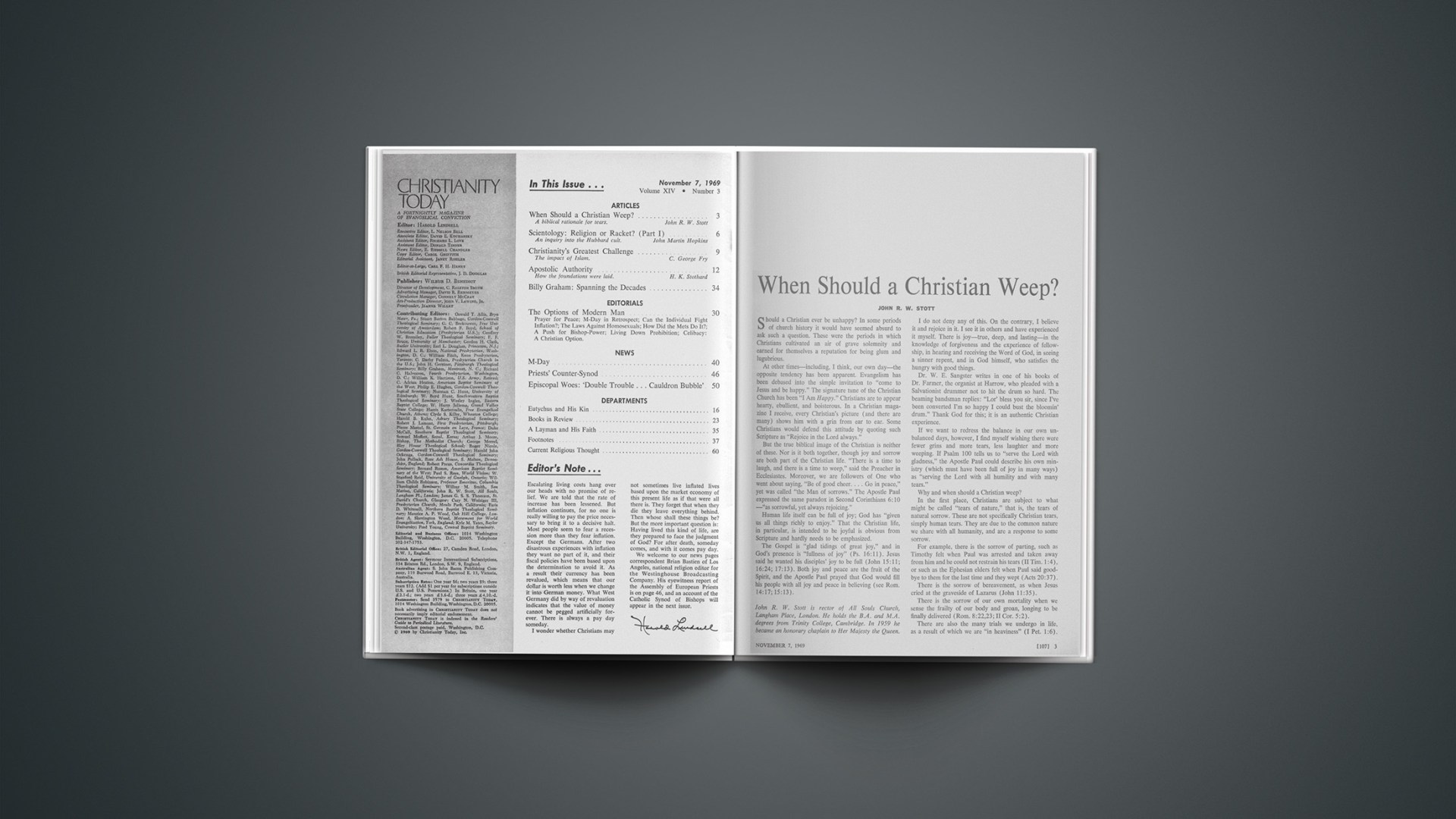

John R. W. Stott is rector of All Souls Church, Langhm Place, London. He holds the B.A. and M.A. degrees from Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1959 he became an honorary chaplain to Her Majesty the Queen.