The Consultation on Church Union has a product to sell. It has salesmen. Now it needs to convince the buyer.

The buyer is the grassroots churchman in the nine participating COCU denominations. The product is the plan of union, a 150-page document approved by the consultation in St. Louis last month (see March 27 issue, page 30). COCU salesmen (information officers of participating churches) will be promoting the union plan as 24 million churchmen begin to “study and respond” to it.

After ten years of talk, the concrete plan was unanimously adopted at the final day of the St. Louis plenary session; some 250 delegates then rose and sang the doxology. Responses and evaluations are to be submitted to the consultation headquarters by January 15, 1972. The consultation doesn’t want official votes on the plan until after that, since revisions are expected to be incorporated into a final plan (see voting procedures for each church in story following).

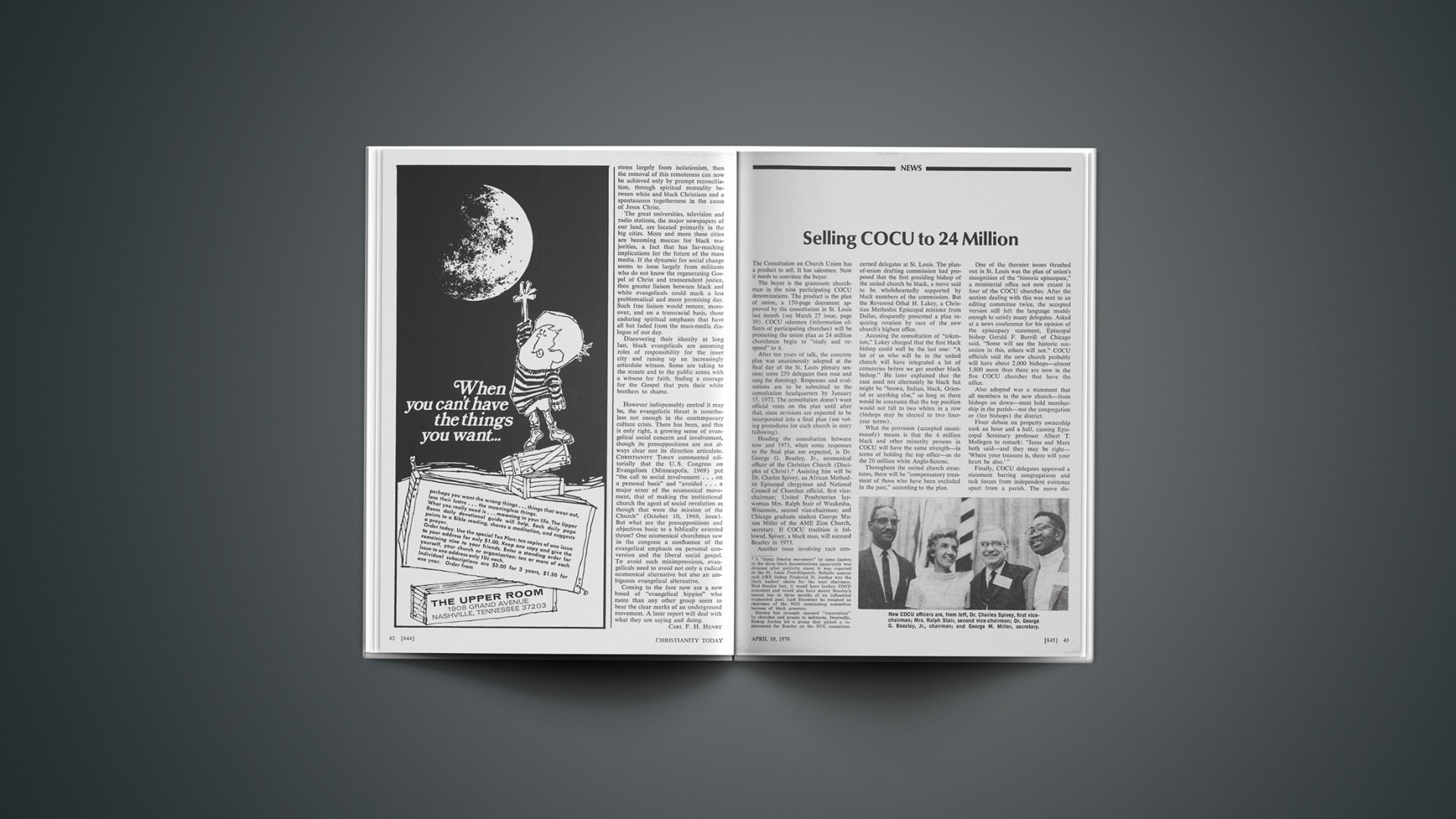

Heading the consultation between now and 1973, when some responses to the final plan are expected, is Dr. George G. Beazley, Jr., ecumenical officer of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ).1A “dump Beazley movement” by some leaders in the three black denominations apparently was dropped after publicity about it was reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Reliable sources said AME bishop Frederick D. Jordan was the black leaders’ choice for the next chairman. Had Beazley lost, it would have broken COCU precedent and would also have meant Beazley’s second loss in three months of an influential ecumenical post. Last December he resigned as chairman of the NCC nominating committee because of black pressure. Assisting him will be Dr. Charles Spivey, an African Methodist Episcopal clergyman and National Council of Churches official, first vice-chairman; United Presbyterian laywoman Mrs. Ralph Stair of Waukesha, Wisconsin, second vice-chairman; and Chicago graduate student George Mason Miller of the AME Zion Church, secretary. If COCU tradition is followed, Spivey, a black man, will succeed Beazley in 1973.

Another issue involving race concerned delegates at St. Louis. The plan-of-union drafting commission had proposed that the first presiding bishop of the united church be black, a move said to be wholeheartedly supported by black members of the commission. But the Reverend Othal H. Lakey, a Christian Methodist Episcopal minister from Dallas, eloquently presented a plan requiring rotation by race of the new church’s highest office.

Accusing the consultation of “tokenism,” Lakey charged that the first black bishop could well be the last one: “A lot of us who will be in the united church will have integrated a lot of cemeteries before we get another black bishop.” He later explained that the race need not alternately be black but might be “brown, Indian, black, Oriental or anything else,” so long as there would be assurance that the top position would not fall to two whites in a row (bishops may be elected to two four-year terms).

What the provision (accepted unanimously) means is that the 4 million black and other minority persons in COCU will have the same strength—in terms of holding the top office—as do the 20 million white Anglo-Saxons.

Throughout the united church structures, there will be “compensatory treatment of those who have been excluded in the past,” according to the plan.

One of the thornier issues thrashed out in St. Louis was the plan of union’s recognition of the “historic episcopate,” a ministerial office not now extant in four of the COCU churches. After the section dealing with this was sent to an editing committee twice, the accepted version still left the language muddy enough to satisfy many delegates. Asked at a news conference for his opinion of the episcopacy statement, Episcopal bishop Gerald F. Burrill of Chicago said, “Some will see the historic succesion in this, others will not.” COCU officials said the new church probably will have about 2,000 bishops—almost 1,800 more than there are now in the five COCU churches that have the office.

Also adopted was a statement that all members in the new church—from bishops on down—must hold membership in the parish—not the congregation or (for bishops) the district.

Floor debate on property ownership took an hour and a half, causing Episcopal Seminary professor Albert T. Mollegen to remark: “Jesus and Marx both said—and they may be right—‘Where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.’ ”

Finally, COCU delegates approved a statement barring congregations and task forces from independent existence apart from a parish. The move disappointed some whose churches hold to congregational polity, especially since an amendment that would have allowed individual congregations to retain title to present property was turned down. But the consultation softened this stance by approving a motion by United Presbyterian stated clerk William Thompson that “present forms of holding property will be maintained during the transition period.” In some ways, this favors churches that vest property in the denomination. The “phase-in” time is expected to last several years.

Ordination standards for presbyters (ministers) in the new church were strengthened by an amendment made by United Presbyterian pastor Cary N. Weisiger of Menlo Park, California. A question on the Scriptures to be asked of candidates now says the “Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments convey the Word of God and are the unique and authoritative standards of the church’s life …” (Weisiger inserted “unique and authoritative”.)

Episcopal ecumenical officer Peter Day wanted the word “are” substituted for the word “convey” in the above wording, thus suggesting that God can reveal propositional truth. His motion lost by a fairly decisive margin.

COCU general secretary Paul A. Crow, Jr., summed up some future sticky wickets for COCU partners. He stressed that COCU enthusiasts envision not a merger of existing churches but a new church with a different life and mission.

“Fundamentally,” he said, “the issue is whether this unfamiliar form of a church has validity.”

RUSSELL CHANDLER

Embracing Cocu

There may be a huge huge-in and when the proposed Church of Christ Uniting gets its ministers together. It’s all right for official guests attending the ministries of the Consultation on Church Union embrace the COCU ministers after the service.

The COCU plenary session in St. Louis last month voted that duly elected representatives (clergy and lay) invited to the service (assuming two are more COCU denominations approve the proposed plan of union) may give each of the COCU ministers “the right hand of fellowship or an embrace and a quiet word of gretting.”

The plan doesn’t say whether the COCU ministers may hug back, or whether they may embrace each other.

Commenting on the addition of the words “or an embrace”—not a part of the original plan of union—Dr. David Colwell of Seattle, a former COCU chairman, said: “We need to loosen up a bit, like the blacks.…”

The earlier description of the consecration service called for “delegated ordained ministers from churches other than the uniting church … to share in this silent laying on of hands. Bishops in the historic episcopate and ministers from non-episcopal churches shall be invited.” The laying on of hands around a large circular table is to be done in silence.

Nuts And Bolts Of Union Vote

What procedures would be necessary in each of the nine denominations participating in the Consultation on Church Union for that church to become a part of the proposed Church of Christ Uniting?

CHRISTIANITY TODAY asked that question of top officials of the nine churches. Any final voting is at least two years away, and denominational officials were not certain in all cases of exact procedures or constitutional requirements. Considered opinions of those surveyed are as follows:

African Methodist Episcopal, African Methodist Episcopal Zion, and Christian Methodist Episcopal Churches—These black denominations, all in the Methodist family, have similar requirements. In each case, the quadrennial General Conference must vote, followed by a vote of the church’s annual conferences. The COCU plan of union (revised) could be submitted to the General Conference of the AME Church no earlier than 1972. If approved there by a two-thirds majority, the annual conferences would then be required to approve the plan by the same majority at their next regular sessions. A final decision could be made by late 1973 or early 1974.

The same procedure applies for the AMEZ Church. (Bishop William J. Walls of Chicago and Professor John Satterwhite of Washington, D. C., both delegates at the St. Louis COCU, may have misunderstood a reporter’s question. But both repeatedly said that the decision for the AMEZ Church would be made at the congregational level and that they expected that COCU would set up a universal procedure under which all nine denominations would individually vote whether to join the united church.) The next AMEZ General Conference will be in May, 1972.

If the CME General Conference (probably 1974) approves the final plan of union by a simple majority, then the annual conferences would vote on the plan at their next meetings. It was not immediately clear whether a two-thirds or three-quarters vote would be needed at that level.

United Methodist Church—The General Conference, meeting in St. Louis this month, is expected to receive and adopt for study the plan of union in its present form. General Conference approval of the final plan could come (a two-thirds majority is believed to be required) in 1972. But the annual conferences would be asked to study the plan, and their voting might not be completed until 1976. Two-thirds of the aggregate vote within the total constituency of the annual conferences would be needed to commit the United Methodist Church to the COCU merger.

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)—Since the Disciples only organized as a denomination (rather than a brotherhood) in 1968, there is no precedent for a vote of this nature. General Assembly approval presumably could not come before 1973. Officials speculate that the thirty-nine regions of the church will probably then vote, as they did in the restructure issue (this required a two-thirds majority). The Disciples’ General Assembly in Louisville in 1971 probably will be asked to set up procedures for the COCU vote.

Episcopal Church—Approval by two consecutive General Conventions is necessary; the earliest of these could be in 1973. The following regular General Convention is set for 1976; a Special General Convention might be called earlier. “Widespread consultation,” and perhaps straw voting by dioceses, will occur between national meetings, an official said. Two-thirds of the House of Bishops and two-thirds of the House of Delegates must approve the plan at each convention. Voting in the House of Delegates will be by orders (lay and clerical votes are counted separately).

United Church of Christ—The General Synod could approve the revised union plan at the 1973 meeting. Then each conference must vote, followed by a vote by each congregation according to its own bylaws. Ultimate decision, then, after approval at the synod and conference level, still belongs to each congregation (some congregations may choose to abide by the vote of the conference to which they belong, however).2According to the present plan of union draft, any local congregation may withdraw from the united church within one year of the formation of the united church’s district council. A majority vote of the local congregation’s communicant members is sufficient; the local church may retain its property. A floor attempt at last month’s COCU plenary session to limit withdrawal to congregations “which had this right in the church law or polity of the uniting church of which it was a part prior to union” failed. It will require a minimum of one and one-half years after the synod votes before congregational voting can be completed.

United Presbyterian Church in the U. S. A., and Presbyterian Church, U. S.—General voting procedures are essentially the same. At the UPUSA General Assembly in Chicago next month, the plan of union doubtless will be referred to a committee set up to interpret and study it and send it to congregations for study. Approval of the revised plan could come as early as the 1972 General Assembly. After that, two-thirds of the presbyteries must approve, and final ratification by another General Assembly (1975 at the soonest) must follow. Only a simple majority vote at the General Assembly level is needed.

The Southern Presbyterian Church procedure differs only in that three-quarters of the presbyteries must approve the plan, rather than two-thirds. If, as some COCU enthusiasts hope, the two Presbyterian bodies unite prior to adoption of the COCU plan, the two-thirds—rather than the three-quarters—vote presumably could apply.

Union (joint) presbyteries between the two bodies (several now exist or are planned in Missouri and elsewhere) could complicate the voting. Delegates in a union presbytery might vote twice, once for the United Presbyterian Church, and again for the Southern Presbyterian Church.

King’S Dream Recaptured

“I wonder why we didn’t listen closer to Dr. King back then?” a white woman mused, obviously moved by King: A Filmed Record … Montgomery to Memphis. “I wonder if it’s too late to find the dream.”

Her reaction was shared by others who viewed the documentary of thirteen years in the life of civil-rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Nearly a million people attended the one-night stand in 1,000 theaters across the country, raising close to $5 million for a special memorial fund.

King the preacher of non-violence, who loved his enemies and sought dignity for his race, dominated the nearly three-hour epic. The film included shots of King in jail in Birmingham in April, 1963, while on the soundtrack he read his now classic “Letter from the Birmingham Jail.” That response to eight clergymen who considered King’s Birmingham demonstrations “unwise and untimely” pointed to the civil disobedience of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego and to the “extremism” of Jesus.

Also in the film were excerpts from many of King’s sermons, including one on Viet Nam he preached in New York’s Riverside Church in 1967.

Transition between segments of the film was provided by actors who read poetry and commented on events. One was Charlton Heston, who read from the Old Testament.

King won nearly universal critical acclaim: it was honest, admitting failure as well as success, but not sentimental. The clergyman’s widow said she was pleased with the production.

Although several theaters in New York and Washington, D. C., reported bomb threats, no violence erupted. That the film did not touch off a wave of violence, as King’s death did in 1968, was attributed by a black Washington columnist to its underlying sense of triumph and the inspiration it gave to take up Martin Luther King’s peaceful dream once again.

Morality Gap Shootout

The good guys and the bad guys met at Morality Gap March 16–18 and ideologically shot it out before nearly 400 Southern Baptist ministers and laymen.

The occasion was the annual seminar sponsored by the Christian Life Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, and the place was the American Motor Hotel in Atlanta.

The meet pitted Playboy magazine public affairs director Anson Mount against Southwestern Baptist Seminary professor William Pinson. Joseph Fletcher, chief guru of situation ethics, hassled with Henlee Barnette, a professor at Louisville’s Southern Baptist Seminary.

“Others may go hopping down the bunny trail but I’ll follow Him who said, ‘I am the way, the truth and the life,’ ” said Pinson, replying to Mount.

There had been enough emphasis, said Mount, on the “terrifying possibilities of sex,” and Playboy’s mission was to move away from that.3Mounting a defense for Playboy’s rising popularity, Mount said its huge circulation made it easy to understand why he had received a letter from Billy James Hargis, the Tulsa evangelist, saying he would be willing to be interviewed by Playboy magazine. Hargis was one of the most vocal opponents of the Atlanta morality seminar.

Fletcher, the Episcopal Seminary professor whose book, Situation Ethics, became the philosophical basis for the new morality in the minds of many, let it be known that the Christian commitment, in his view, might call for all kinds of behavior.

Noting that Jesus broke laws, Fletcher said: “I am prepared to argue that the Christian obligation calls for lies and adultery and fornication and theft and promise-breaking and killing sometimes, depending on the situation.”

The only laws Jesus broke were ceremonial laws, countered Barnette, and “nowhere did Jesus abrogate the moral law.” Fletcher’s system, he said, “is not loving enough, not situation-oriented enough, and not theological enough.”

Another Southern Baptist Seminary professor, Frank Stagg, in an address on morality and militarism, charged that the United States is the most militaristic country in the world.

“The alleged massacre of My Lai, if true, was no accident,” said Stagg. “Whatever the dimension of personal guilt, the system itself produces what is alleged to have occurred at My Lai. For it we are all guilty.”

Following the speech, Owen Cooper, a Yazoo City, Mississippi, layman, told Stagg he had done “as good a job of overkill as you accused the military of in Viet Nam.”

Sex education also entered the Morality Gap fray. However, there wasn’t enough disagreement for a debate between David Mace, former head of the Sex Information and Education Council in the United States, and James Dunn of the Texas Baptist Christian Life Commission.

“The Christian view of sex is a hodgepodge of superstition and prejudice that answers to no set of coherent ethical principles,” said Mace.

Dunn blasted Southern Baptist leadership for not doing more about sex education in the churches. “Ten negative letters constitute an avalanche in Nashville,” he said.

The Atlanta meeting stirred controversy across the Southern Baptist Convention, primarily over the presence of Mount, Fletcher, and Mace. There was also unhappiness in some circles because Negro legislator Julian Bond of Georgia, a black-power advocate, was a speaker.

Participants enthusiastically endorsed a resolution praising the meeting, hoping it would at least muffle anger that could explode when the Southern Baptist Convention meets in Denver this June.

WALLACE HENLEY