One of the major features of the new theology is that it is man centered. Attention is focused on those features of human life that highlight what it means to be human. Things like history, culture, subjectivity, sensitivity, secularity, and style of life occupy the center of attention. So far as there is a biblical foundation, it is the command to love one’s neighbor. Jesus is characterized as the man who empties himself for the sake of others in a kind of self-giving that is the model for human existence. In Jesus we see not so much the character of a transcendent God as what it means to live as though ultimate reality were personal. The good news does not have to do with theological or historical facts as such. Rather, it is the proclamation that there is a style of life dominated by a loving concern for others that frees us to be our real selves, and that this style of life is rooted in persons and how they relate to one another. Thus at least two ideas predominate: Theology is not doctrinal in the old sense of elaborating facts about man and God, and theology is a kind of existential anthropology centered in the unique characteristics of persons and their relations.

This is, of course, an over-simplified summary of the enormous variety of existential and Jesus-centered humanisms. There simply is no general agreement among proponents of the new theology as to what separates the new from the old except the agreement that traditional supernatural Christianity must be shorn of its outmoded way of thinking and recast into strictly human and this-worldly terms.

Evangelical Christians reject this mandate—but not because they discount the importance of a style of life dominated by love of neighbor. Nor do they wish to discount the importance of persons as such or of the relations between persons—as, for example, those between the races. What they reject is the assumption that commitment to the loving life produces it or even that trying to live it produces it. Indeed, the evangelical believes that the point of the good news of the Gospel is how the loving life has been made possible. He feels that the new theologian strips the good news of the very reasons why anyone would want to call it good news and go into all the world to preach it. Moreover, despite the emphasis that the new theology places on the importance of persons and the conditions of personal existence in this world, it destroys its own ground for this kind of emphasis. Not only is the substance of the good news dissipated; the persons for whom it was intended are explained away as concrete realities. Thus while we may have started with lost persons seeking salvation, we end with neither persons or salvation. Instead, we have something akin to Eastern religious goals—the extinction of persons as such.

For the contemporary liberal theologian, Christian truths are existential rather than propositional. For example, the importance of Christ’s resurrection is to be found, not in the idea that as a matter of fact God raised Jesus from the dead, however properly that must be understood, but in the existential truth that—as Bultmann, for one, put it—a “resurrection” occurs in us upon hearing the Gospel. Now this is not to say that evangelicals deny such things as existential truth or that they don’t hold for resurrection in the Pauline sense of rising from our dead selves in Christ. It is only to say that evangelicals do not reduce the Gospel to nothing but existential truth, that they reject the idea that statements about our salvation must be taken as nothing but pronouncements concerning how we intend to live. Evangelicals hold that their pronouncements and those that are the substance of Scripture are factual in some non-subjective and historical sense. They are factual in a way appropriate to them no less than the claim that one’s wife loves him is factual in a way appropriate to that assertion. And one could go on to say that these claims are factual, not only because we are committed to their truth, but because we have good reasons to believe them, just as we may have good reasons to believe that our wives love us. These claims are factual in the same sense that Paul had good reasons to believe that Jesus Christ became his Lord and Saviour during his Damascus trip; indeed, not to believe this would have been unjustified and irrational in his case.

The denial by contemporary theologians of the historical and factual character of, for example, what God has done on our behalf leads some of them to say that traditional doctrinal statements about God are no longer relevant or even intelligible to contemporary man. We must talk, we are told, about things like life styles; this is what Jesus really had in mind, despite what he was reported to have said, and only this can make sense today. And if it seems that God has died, then what seems to have died is the old conception of him. This death, we are urged to believe, is something that we can properly and enthusiastically accept, since it is the new understanding of a divine that emerges from within human life itself that will bring about, it is hoped, the reappearance of God, a God that is relevant and intelligible because it—and I use the pronoun deliberately—is no longer a transcendent supernatural being.

The upshot is that we are now to talk not about what God does or says but about what man does or is saying. No wonder many laymen are puzzled by what they hear or don’t hear in their churches today. What is stressed is the quality or style of living—not “thus saith the Lord.” The new theology confronts us with the paradox of trying to say that the one who knows God best is the one who knows him least in the old sense of what is meant to know God. In any event, it is what men say—not what God says—that is now taken to be theologically relevant or interesting. Yet if we do take the new theologian seriously we are confronted with the possibility that there may not be anyone to say anything of any sort—to say nothing of there being a God who says something. The issue becomes the question of the existence of persons themselves as well as the existence of propositional revelation.

I want to examine the two central ideas of the new theology that I identified earlier: the rejection of propositional revelation for existential insight, and the rejection of supernatural theism for existential humanism. The new theology shifts attention from factual to existential issues by referring to what is sometimes called the existential encounter. Here the important thing is existential rather than propositional truth. Existential truth is that which has to do with the quality of living rather than correct beliefs. The evangelical cannot reject such existential truth as the Christ-centered life, but he wishes to conjoin the possibility of this life with certain propositional truths about Christ and one’s beliefs concerning them that are in accord with New Testament injunctions. My point is that the liberal theologian who places his emphasis upon existential truth undercuts the very ground of that truth, however much he may want to preserve and emphasize it.

It is only fair to note that the original intention of liberalism was to understand revelation and Christian belief in a way that would free it of the propositional claims that were supposed to scandalize the modern mind—claims that, according to Brunner, and others, could be attributed to the peculiar aberrations of American fundamentalists, whom Brunner charged with making Christianity unpalatable for all but unsophisticated minds. Now of course it is not possible to defend all evangelicals against these charges, but the point is that what Brunner called for and the way he implemented it led to the very liquidation of what he was trying to preserve—the living self-disclosure of God in Christ.

Among other things, Brunner and other early neo-orthodox existentialists wanted to emphasize that knowing God is something personal, something lived or experienced rather than merely thought. God reveals himself, they argued—not information about himself. Taken this way, revelation could escape the difficulties of literalism, they hoped. Thus the existential theologian was led to saying things like, “We know God existentially as encounter rather than propositionally as fact.”

Now no evangelical would want to invalidate existential encounter with God. But these claims lead to something very different from their original form and intent. Surely it is true that we know the Person of Christ, in a personal way—not just things about him. This is, I take it, what it means to be an evangelical believer. But it seems to me that it is only because we do know things about Christ that we can say that he has disclosed himself to us in a personal way. It is only because we do know certain things that we can say that revelation is, among other things, a personal self-disclosure. Hence if there is any revelation at all, it must be propositional in at least this sense. I cannot imagine how I could get to know anyone in a personal way without also getting to know many things about him that make my relationship with him precisely what it is—personal. So, far from eliminating propositional revelation, revelation as personal encounter necessitates it.

It is not plausible to argue that God deliberately limits his self-disclosure to exclude propositions, whether in his encounter with persons or in other ways, such as the inspiration of the written Word. Indeed, how could he deny us those truths that are necessary to justify our knowing and trusting him existentially? I cannot conceive of any kind of personal self-disclosure that is not also a propositional disclosure, although, of course, personal self-disclosure is never just that alone. But so far as I know, no evangelical believer has ever claimed that revelation was merely propositional. Indeed he of all people has emphasized the centrality and necessity of knowing God through personal encounter with Christ. Thus the idea that one can safeguard existential truth by scuttling propositional truth is misconceived. Quite the contrary; we can safeguard existential Christian truth only by preserving the propositional truths that make it possible.

The man who opens his heart to Christ gets to know something he didn’t know before, and he can say what he knows even though not all of what he knows can be said. To object to explicit doctrinal and propositional statements about God is like arguing that we can’t know or say anything about something unless we can know or say everything there is to be known or said about it. It is precisely what we do know and can say about God propositionally (rather than what we don’t know or can’t say propositionally) that gives direction and meaning to our faith. And the fact that we can do this does not make us captive to some fixed mode of thinking, nor does it make us captive to some legalistically interpreted Christian doctrine.

If a man loves his wife, he will know many things about her, and what he knows or what she has disclosed to him in their relationship will be no less known for having failed to exhaust the mystery of her being. Nor is what is known distorted for having been expressed propositionally. The man’s wife remains a mystery but not a wholly inscrutable one. Love opens up the understanding. This is why getting to know God requires obedience to the First Commandment. Those who hold for existential or propositionless revelation are not just limiting what they can know or say, they are limiting what God can say. The question is not what God could or would do or say that is intelligible or relevant, rather it is what God has done or said or is doing or saying today as regenerated believers discover for themselves. It is these believers and not the theologian who speak for the body of Christ. The theologian confuses his “radical openness” (as he calls it) for the claim that God does or doesn’t work, for example, in supernatural ways, or that God really is the future of man, the quality of life, community, love, or something else—not, for example, the traditional Heavenly Father. Terms like “Heavenly Father,” he argues, must be understood symbolically or existentially. They do not refer to objective facts of a certain kind for which the term or statement using it is the appropriate expression. But for whom does the theologian speak?

The new theology’s rejection of supernatural propositional revelation can be best understood, I believe, through a look at the “truth as encounter” theory expounded by Martin Buber. According to Buber’s influential exposition of it human existence has two forms: the I-it connection and the I-thou encounter. The latter is personal and gives to human existence its unique significance. For the existential theologian, the I-thou encounter embraces what is meant by God, knowing God, revelation, truth, and spiritual reality. For these thinkers, what is ultimately significant is what Buber called “betweenness”—the hyphen, so to speak, in the I-thou—not the I, or thou, the you, me, or God, which are, as traditionally used, abstractions torn from the reality that is the encounter. A similar coalescence of real concrete persons into process or something else occurs in Hegelian as well as Buber-based theologies.

The biblical position is that all three are important: the person who is in encounter with other persons and God, the God to whom we are reconciled in Christ, and the supernatural grace that reconciles us all one to another. The existential theologian mistakenly thinks that by deemphasizing the I and thou—distinct personal beings as such—he is able to keep the relationship from becoming an I-it connection in which one relates to another person by treating him as an object to be used. But what the existentialist succeeds in doing is to confuse the logical distinction that one must make between ourselves as persons and the Person of God for the ontological distinction that makes us into isolated island things. There is no reason why we cannot speak of real persons and a real Personal God without also at the same time committing ourselves to some metaphysical theory that abstracts us or God from living relationships. I can refer to my wife as a concretely real and distinct person without at the same time jeopardizing my relationship with her or getting embedded in a metaphysical theory that commits us both to isolation from each other. I can properly refer to God as the God “in whom I live and move and have my being” as well as the God who is concretely real and distinct in the Person of Christ without doing violence to his mystery and majesty or jeopardizing my relationship with him. The encounter is no less an encounter for our having made the logical distinction. It is the existentialist theologian who jeopardizes that relationship by endowing it with a special metaphysical significance. The strategy he pursues to keep God in the encounter, to preserve the encounter and keep it alive, tends to remove the very reasons why it should be preserved at all or, for that matter, should be referred to as an encounter. Any practicing believer knows that it takes more than “encounter” therapy to keep the encounter alive. It takes regenerate persons whose relationship to each other is centered in the Person of Christ.

Brunner argued that propositional truth, truth as idea, or doctrine, is Greek and unbiblical. Today existential theologians have come to argue that “truth as encounter” implies no particular ideas or doctrines at all—not even a necessarily meaningful use of the word God. What started as a move to preserve biblical truth in its existential sense ends in its liquidation. The same razor that Brunner used to shave off what he feared as fundamentalist literalism is used by later generations of existentialist theologians to shave off the biblical ideas that were still firmly part of Brunner’s thinking. With the doctrine of truth as encounter, that is, existential truth, the new theology is free to consider any belief whatever or no particular belief at all as Christian, since being Christian has to do with a style of life and not with beliefs or facts or a certain kind.

The encounter or existential view of truth is the epistemological key to the new theology. But it is also the Achilles heel of that theology because it is in the analysis of the encounter itself that the failure of the theory becomes apparent. Moreover, truth as encounter is itself an abstraction from the whole of Christian revelation. When God encounters man, He encounters him in history, in nature, and in the written as well as the living Word. All these encounters are no less propositional for being personal or no less personal for being propositional.

The living religious experience that liberalism sought to preserve is lost because the real persons and the real God of that experience get replaced by a third kind of something—a historical process, a community, a togetherness, a betweenness, or what have you. Labels abound in the vocabulary of the contemporary theologian.

The original Gospel that justified our hope for eternal life now has no established or recognizable form by which our interest in it can be justified. Theologians must rediscover what the early Church knew and experienced, but that rediscovery cannot be self-defeating if it is to escape the plight of much theology and theologizing today.

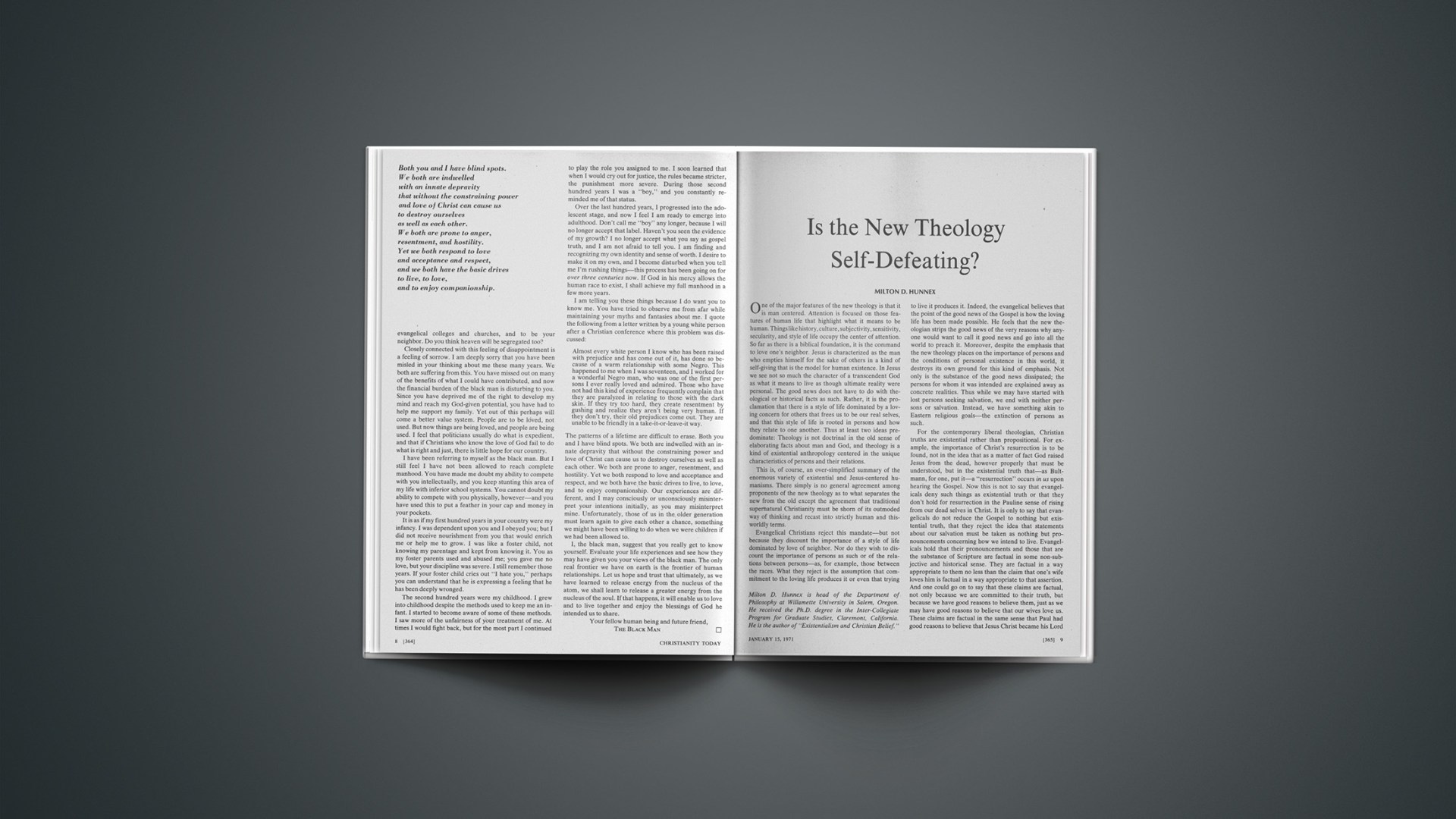

Milton D. Hunnex is head of the Department of Philosophy at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon. He received the Ph.D. degree in the Inter-Collegiate Program for Graduate Studies, Claremont, California. He is the author of “Existentialism and Christian Belief.”