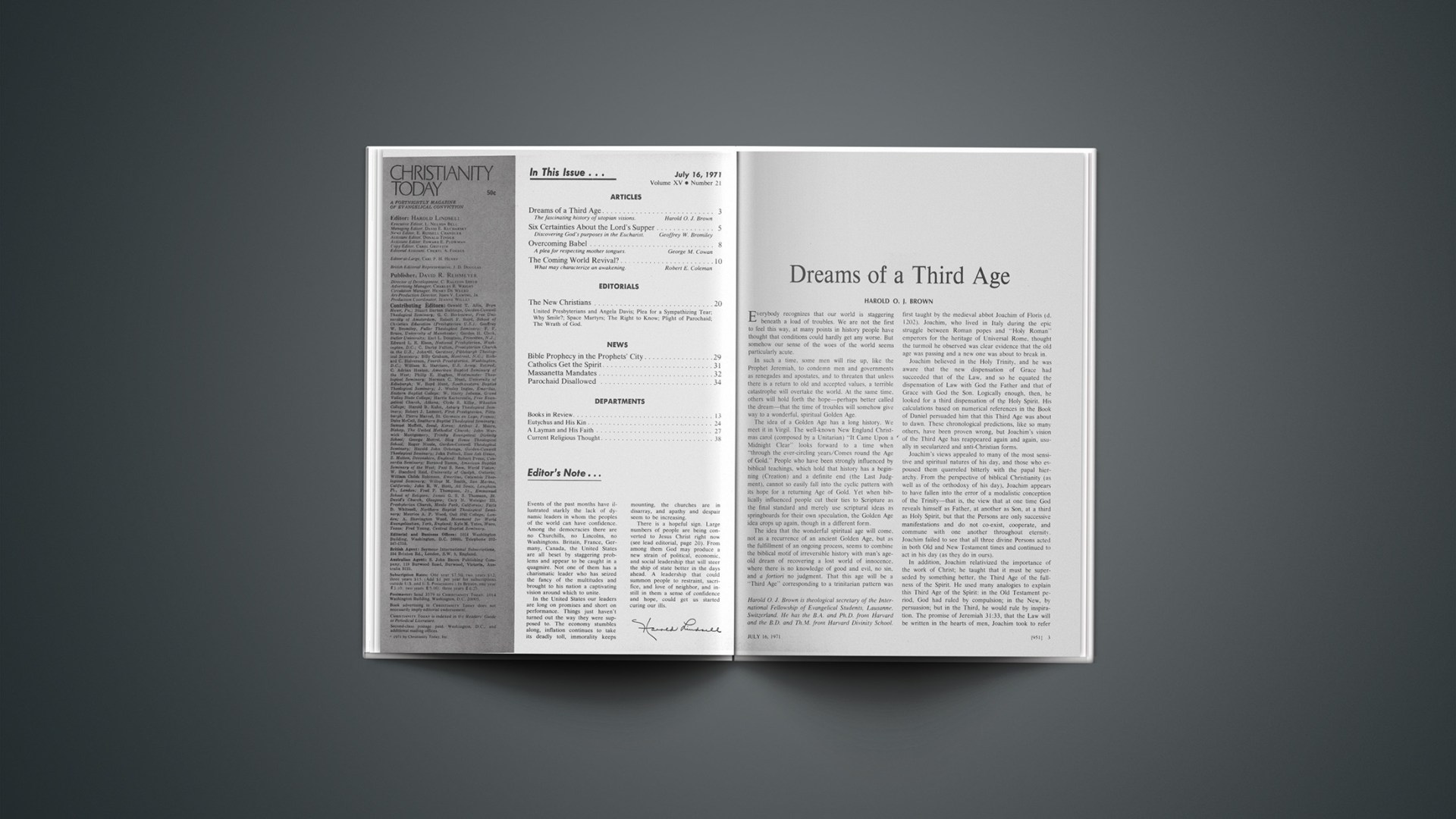

Everybody recognizes that our world is staggering beneath a load of troubles. We are not the first to feel this way, at many points in history people have thought that conditions could hardly get any worse. But somehow our sense of the woes of the world seems particularly acute.

In such a time, some men will rise up, like the Prophet Jeremiah, to condemn men and governments as renegades and apostates, and to threaten that unless there is a return to old and accepted values, a terrible catastrophe will overtake the world. At the same time, others will hold forth the hope—perhaps better called the dream—that the time of troubles will somehow give way to a wonderful, spiritual Golden Age.

The idea of a Golden Age has a long history. We meet it in Virgil. The well-known New England Christmas carol (composed by a Unitarian) “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear” looks forward to a time when “through the ever-circling years/Comes round the Age of Gold.” People who have been strongly influenced by biblical teachings, which hold that history has a beginning (Creation) and a definite end (the Last Judgment), cannot so easily fall into the cyclic pattern with its hope for a returning Age of Gold. Yet when biblically influenced people cut their ties to Scripture as the final standard and merely use scriptural ideas as springboards for their own speculation, the Golden Age idea crops up again, though in a different form.

The idea that the wonderful spiritual age will come, not as a recurrence of an ancient Golden Age, but as the fulfillment of an ongoing process, seems to combine the biblical motif of irreversible history with man’s age-old dream of recovering a lost world of innocence, where there is no knowledge of good and evil, no sin, and a fortiori no judgment. That this age will be a “Third Age” corresponding to a trinitarian pattern was first taught by the medieval abbot Joachim of Floris (d. 1202). Joachim, who lived in Italy during the epic struggle between Roman popes and “Holy Roman” emperors for the heritage of Universal Rome, thought the turmoil he observed was clear evidence that the old age was passing and a new one was about to break in.

Joachim believed in the Holy Trinity, and he was aware that the new dispensation of Grace had succeeded that of the Law, and so he equated the dispensation of Law with God the Father and that of Grace with God the Son. Logically enough, then, he looked for a third dispensation of the Holy Spirit. His calculations based on numerical references in the Book of Daniel persuaded him that this Third Age was about to dawn. These chronological predictions, like so many others, have been proven wrong, but Joachim’s vision of the Third Age has reappeared again and again, usually in secularized and anti-Christian forms.

Joachim’s views appealed to many of the most sensitive and spiritual natures of his day, and those who espoused them quarreled bitterly with the papal hierarchy. From the perspective of biblical Christianity (as well as of the orthodoxy of his day), Joachim appears to have fallen into the error of a modalistic conception of the Trinity—that is, the view that at one time God reveals himself as Father, at another as Son, at a third as Holy Spirit, but that the Persons are only successive manifestations and do not co-exist, cooperate, and commune with one another throughout eternity. Joachim failed to see that all three divine Persons acted in both Old and New Testament times and continued to act in his day (as they do in ours).

In addition, Joachim relativized the importance of the work of Christ; he taught that it must be superseded by something better, the Third Age of the fullness of the Spirit. He used many analogies to explain this Third Age of the Spirit: in the Old Testament period, God had ruled by compulsion; in the New, by persuasion; but in the Third, he would rule by inspiration. The promise of Jeremiah 31:33, that the Law will be written in the hearts of men, Joachim took to refer to the Third Age, in which men would act spontaneously to fulfill God’s will. Under the Old Testament, there was only the promise of Grace; under the New, the fulfillment of that promise was enacted and mystically achieved in the sacraments; in the Third Age, there would no longer be types and figures, but complete fulfillment.

In this respect, Joachim advanced the idea of the purification and renewal of all things associated with the Second Coming to the here-and-now. His idea differed from the usual pre-millennial views, however, in that it did not involve a catastrophic judgment. The whole world would, he thought, pass over by a kind of transformation into this blessed condition.

In the centuries since Joachim, the idea of a Third Age—one in which old principles of justice and right, old ideals, and old loyalties will be superseded by entirely new ones—has frequently recurred. Imperial Russia looked upon Moscow as the Third (and ultimate) Rome, and the Russian Communists have perpetuated this messianic vision in a totally de-Christianized form. (The Basel psychologist Arnold Kuenzli maintains that for Karl Marx the Revolution was a secularized, atheistic surrogate for the Second Coming of Christ.) The most famous, or infamous, Third Age is of course the Third Reich of Adolf Hitler, which he conceived of in ordinary historical terms as the successor to the Holy Roman and Bismarckian Empires, but which in a deeper sense represented a Messianic Third Age. The messianic mysticism in which the Third Reich indulged heavily was of a secular and apostate kind. All utopian political or social visions tend to embody a kind of apostate political messianism; in some, such as the Great Society of Lyndon B. Johnson, the religious undertones are very faint, but in others they are quite strong.

Hitler is dead and gone, but false messianic mysticism keeps coming back to plague us. The 1968 General Assembly of the World Council of Churches at Uppsala, Sweden, was dominated by the vision of all things made new—a theme taken from Revelation 21:5, but taken out of context, and absolutely bypassing the question of judgment. All visions of peace and plenty are apostate and anti-Christian if they bypass moral and spiritual distinctions and leave no place for the reality of divine judgment. This holds true whether or not the authors claim, as the WCC theologians did, that their visions come from the Bible and represent the outworking of God’s plan for history.

While the ostensibly Christian WCC invokes Scripture to lend a religious sanction to what is in effect this-worldly secular messianism, other voices dispense entirely with the religious element; they promise a new world of joy and wonder just ahead completely independent of God or any divine plan. Thus Professor Charles A. Reich of Yale gives us, in The Greening of America (Random House, 1970), a vision of a new world order arising out of a change in consciousness. In his view, certain aspects of the current scene that seems evil and threatening to those still committed to traditional Christianity—such things as drug use, contempt for productive work, sexual licentiousness, and pornography—are in fact only the signs or even the agents of the new consciousness.

Perhaps the symbolism escaped Professor Reich, or perhaps he is aware of it, but he labels this “new consciousness” Consciousness III. He sees it as following upon Consciousness I (small-town, largely Christian traditional values) and Consciousness II (materialistic, liberal, progress-oriented values), and maintains that it represents the culminating, liberating age of spiritual freedom and maturity.

Reich repudiates Christianity as a failure because it encourages man to expect fulfillment in heaven rather than here and now. He simply discards it. Other prophets claim that a reversal of all Christian values is necessary for the breaking-in of the Third Age. Among these is the “death of God theologian” Thomas J. J. Altizer (see CHRISTIANITY TODAY, January 7, 1966, p. 46). Not until we admit that the God of Scripture is dead, reverse all “satanic” (=biblical) morality, and finally acclaim ourselves as “the Great Humanity Divine” will the wonderful Third Age come.

Altizer, who is consciously operating against a Christian background, develops his vision in a more deliberately anti-Christian way than Reich, but the two have in common a glorification of man through a deliberate reversal of biblical (and rational) norms. With Altizer the reversal is based on principle and is part of a thought-out program, whereas with Reich it simply seems to be happening; but the net effect is that both these theorists, like the infamous practical politician Adolf Hitler before them, repudiate “external” law of every kind and see mankind as immune from any judgment, divine or otherwise.

Things have evidently come a long way since the days of Abbot Joachim, who would have been horrified to see his vision of the Third Age perverted in this way. Yet he unwittingly contributed to it, not only by coining some key phrases, but also by limiting the authority of the Father and the Son to specific periods in (past) history, by relativizing the work of Christ into a figure or type of something still better yet to come, and above all by reducing the reality of divine judgment and the condemnation that will fall on the ungodly to a passing shadow across the bright path into the future.

Faced with one or another of these Third Age dreams, whether from Marx, Hitler, or Charles Reich, the Christian must hold to the biblical principle that the world will be judged. There will be a transformation, but mankind cannot bypass Christ. Although we may spurn him as Saviour, we will still have to face him as Judge. These Third Age visions do away with moral categories: the only standard becomes “openness to the future,” or something similar. This overlooks the fact that the future, until Christ comes again, is just more of the present age, grown a little older, and that the present age is doomed to perish, with all its brilliance, all its misery, all its wisdom, and all its self-deception.

The judgment of God cannot be avoided, nor will any slogans or visions of a Third Age beyond Law and Grace save one in that day. The only salvation lies in faith in the One in whom all the demands of Law are met and all the promises of Grace come true, Jesus Christ: the Christ of Scripture and of history, of prophecy, faith, and hope. He has been slain, he is risen, he has ascended, and he is coming again—not to establish a visionary Third Age beyond good and evil, but to judge the living and the dead. And of his kingdom there shall be no end.

Harold O. J. Brown is theological secretary of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. Lausanne, Switzerland. He has the B.A. and Ph.D. from Harvard and the B.D. and Th.M. from Harvard Divinity School.