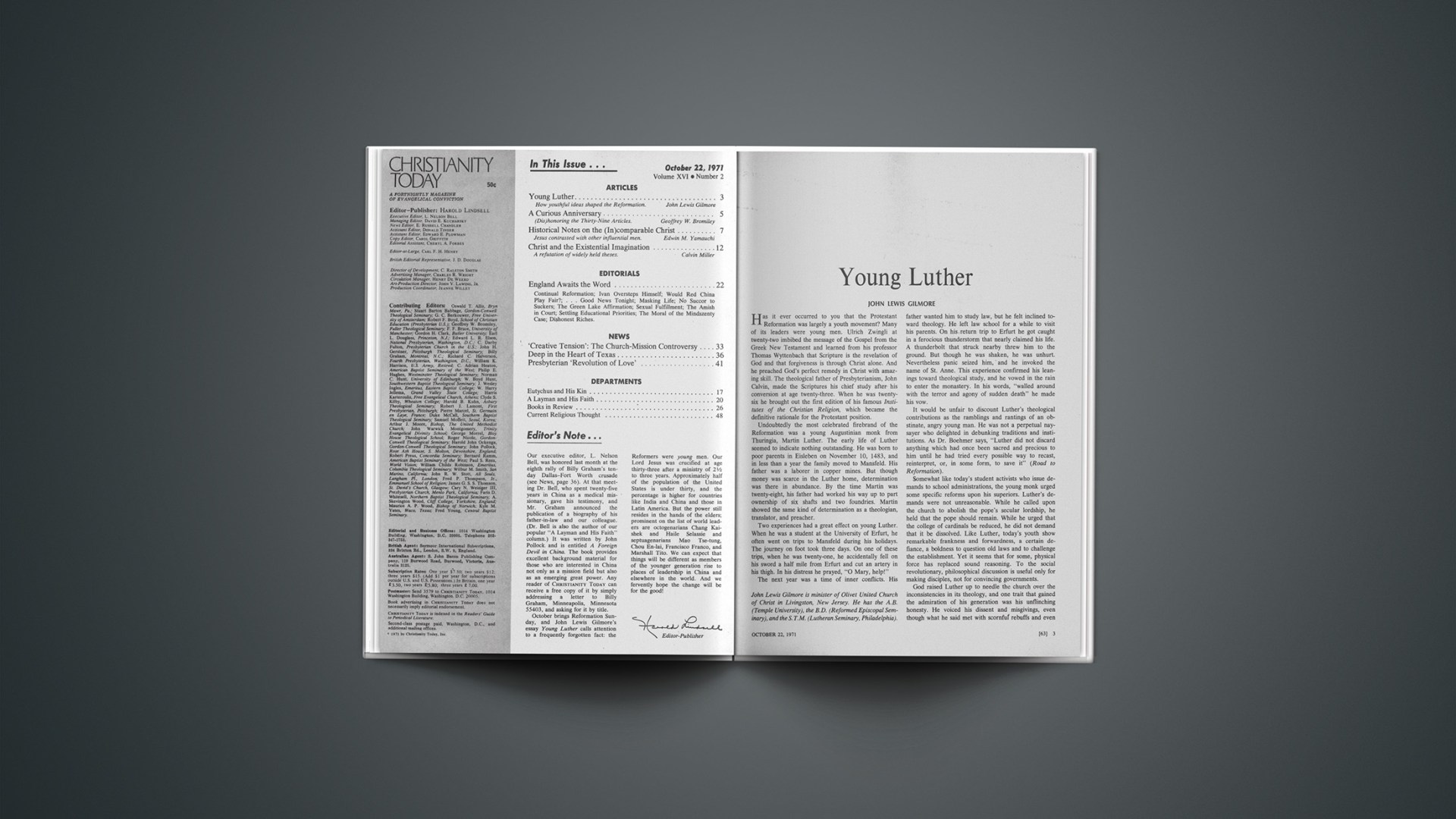

Has it ever occurred to you that the Protestant Reformation was largely a youth movement? Many of its leaders were young men. Ulrich Zwingli at twenty-two imbibed the message of the Gospel from the Greek New Testament and learned from his professor Thomas Wyttenbach that Scripture is the revelation of God and that forgiveness is through Christ alone. And he preached God’s perfect remedy in Christ with amazing skill. The theological father of Presbyterianism, John Calvin, made the Scriptures his chief study after his conversion at age twenty-three. When he was twenty-six he brought out the first edition of his famous Institutes of the Christian Religion, which became the definitive rationale for the Protestant position.

Undoubtedly the most celebrated firebrand of the Reformation was a young Augustinian monk from Thuringia, Martin Luther. The early life of Luther seemed to indicate nothing outstanding. He was born to poor parents in Eisleben on November 10, 1483, and in less than a year the family moved to Mansfeld. His father was a laborer in copper mines. But though money was scarce in the Luther home, determination was there in abundance. By the time Martin was twenty-eight, his father had worked his way up to part ownership of six shafts and two foundries. Martin showed the same kind of determination as a theologian, translator, and preacher.

Two experiences had a great effect on young Luther. When he was a student at the University of Erfurt, he often went on trips to Mansfeld during his holidays. The journey on foot took three days. On one of these trips, when he was twenty-one, he accidentally fell on his sword a half mile from Erfurt and cut an artery in his thigh. In his distress he prayed, “O Mary, help!” The next year was a time of inner conflicts. His father wanted him to study law, but he felt inclined toward theology. He left law school for a while to visit his parents. On his return trip to Erfurt he got caught in a ferocious thunderstorm that nearly claimed his life. A thunderbolt that struck nearby threw him to the ground. But though he was shaken, he was unhurt. Nevertheless panic seized him, and he invoked the name of St. Anne. This experience confirmed his leanings toward theological study, and he vowed in the rain to enter the monastery. In his words, “walled around with the terror and agony of sudden death” he made his vow.

It would be unfair to discount Luther’s theological contributions as the ramblings and rantings of an obstinate, angry young man. He was not a perpetual naysayer who delighted in debunking traditions and institutions. As Dr. Boehmer says, “Luther did not discard anything which had once been sacred and precious to him until he had tried every possible way to recast, reinterpret, or, in some form, to save it” (Road to Reformation).

Somewhat like today’s student activists who issue demands to school administrations, the young monk urged some specific reforms upon his superiors. Luther’s demands were not unreasonable. While he called upon the church to abolish the pope’s secular lordship, he held that the pope should remain. While he urged that the college of cardinals be reduced, he did not demand that it be dissolved. Like Luther, today’s youth show remarkable frankness and forwardness, a certain defiance, a boldness to question old laws and to challenge the establishment. Yet it seems that for some, physical force has replaced sound reasoning. To the social revolutionary, philosophical discussion is useful only for making disciples, not for convincing governments.

God raised Luther up to needle the church over the inconsistencies in its theology, and one trait that gained the admiration of his generation was his unflinching honesty. He voiced his dissent and misgivings, even though what he said met with scornful rebuffs and even endangered his life. He showed this same honesty in the confessional box, where his confessions of sin were so full that the director of the cloister said, “God is not angry with you. You are angry with God.” The bureaucrats of Rome resented this outspokenness. But some present-day Catholic scholars admire him for it; Karl Adam, for instance, praises Luther’s “warm penetration of the essence of Christianity, his passionate defiance of all unholiness and ungodliness, … his surging soul-shattering power of speech, and not the least that heroism in the face of death with which he defied the powers of this world” (One and Holy).

Young people liked Luther because he was shrewd without being stuffy, pioneering without being disrespectful. His dogmatism was enlivened with touches of playful irony. His manner in the pulpit was both vigorous and vivid. All through his life he retained a passionate temperament.

Early in life Martin mastered logic, and he showed his fondness for the syllogism to his dying day. He could argue his case for Christ persuasively and cogently. The Reformation got off to a rousing start partly because of Luther’s tremendous ability to defend his position. If he had been unable to convince his colleagues of his views, the Reformation in Germany would have fizzled.

The arena of debate in the Middle Ages was the disputation. The disputation had all the drama of the courtroom, all the excitement of a football game. These disputations were a regular part of the academic program and put both students and faculty to the test. They stimulated thought, and in the case of Luther they convinced a generation. A professor would write the theses to be demonstrated and a student would be chosen to defend them in a large auditorium before professors and students.

Luther twice defended the ninety-five theses, written in 1517 and nailed to the Wittenberg church door. The first defense was before his own order in May, 1518, the second before Cardinal Cajaetan in October. Equally interesting are his other disputations: the disputation against scholastic theology in 1517; the Heidelberg disputation in 1518, which treated the place of works in the salvation process; the disputation on faith and law in 1535; the disputation on man in 1536; in the same year the disputation on justification; and, rounding them out, the disputations against the power of a council and against antinomianism.

Luther’s home became a favorite meeting place of students, and he loved to talk with them. A number of talented young scholars flocked to him. In time way-out Wittenberg “resembled a swarming ant-hill.”

Two hundred Wittenberg students armed with spears traveled with Luther, Melanchthon, and Karlstadt to Leipzig for the disputation with Eck. And young men accompanied him from the debates, for in arguing his cause he picked up more admirers. They admired his candor. They were convinced by his reasons and captivated by his Christ. Luther was heartened by this enthusiastic response; student support cheered him. After the Heidelberg disputation (1518) he wrote to Spalatin, “I now confidently hope that the true theology of Christ which those men who have grown old in their sophistical opinion [the Erfurt Occamists] reject, will pass over to the younger generation.”

Luther’s deep concern for youth is reflected in a searching sentence in his Open Letter to the Christian Nobility: “The young folk in the midst of Christendom languish and perish miserably for want of the Gospel, in which we ought to be giving them constant instruction and training.” As a young man he had experienced anguish, and he knew that the Gospel of Christ was adequate to answer the yearnings of the young heart.

Luther thought that through a prayer-filled life he could get rid of his nagging guilt and quiet his conscience. But he didn’t find monasticism a soul cure, and he bluntly said so. He proved that one can be upright and still be up-tight. Luther once confessed that he never considered himself absolved. He later discovered that he was trusting in his confessions, rather than in the promise of Christ. He was trying to clear his own record, rather than resting in the satisfaction of Christ who bore his sins. Once he realized that he was saved by the merits of Jesus Christ and not by his own strivings, it seemed as if the gates of paradise opened, and for the first time he knew true freedom. This theology, which got Luther into so much trouble, is taken from the pages of the New Testament.

We have lost much of the bite and explosiveness of Luther’s message in our churches. We are more apt to coddle Pharisees than to shock them. We want to keep the peace, sometimes at the expense of offending God. Luther dared to object to the system, to disturb the peace, and this won him the support of the younger generation. But we cannot attribute his success to the fervor of youthful rebellion. The Reformation became a lasting movement, rather than a passing revolt, because behind Luther’s youthful zeal and complete honesty was the substantial and stirring message of the Gospel of sovereign grace.

John Lewis Gilmore is minister of Olivet United Church of Christ in Livingston, New Jersey. He has the A.B. (Temple University), the B.D. (Reformed Episcopal Seminary), and the S.T.M. (Lutheran Seminary, Philadelphia).