On the afternoon of October 30, exactly seven months after the fall of Saigon, a Royal Air Lao twin-engine DC-3 landed at Bangkok, Thailand. Aboard were fourteen persons, including seven missionaries and one of their children, who had been held captive by the Vietnamese Communists since the second week of March. They were accompanied on the flight from Hanoi by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Prince Sadruddin Khan of Pakistan. Khan and his aides had spent months negotiating their release.

Standing in a light drizzle to greet them were a dozen friends, mission officials, and 17-year old Geraldine Mitchell, daughter of Mrs. Betty Mitchell, one of the returning missionaries. Mrs. Mitchell’s husband Archie, a Christian and Missionary Alliance hospital administrator, had been taken captive with two other missionary workers in 1962, and he has not been heard from since then.

Also on hand were a number of embassy officials, including the ambassadors of the United States, Canada, the Philippines, and Australia, plus a bevy of newsmen.

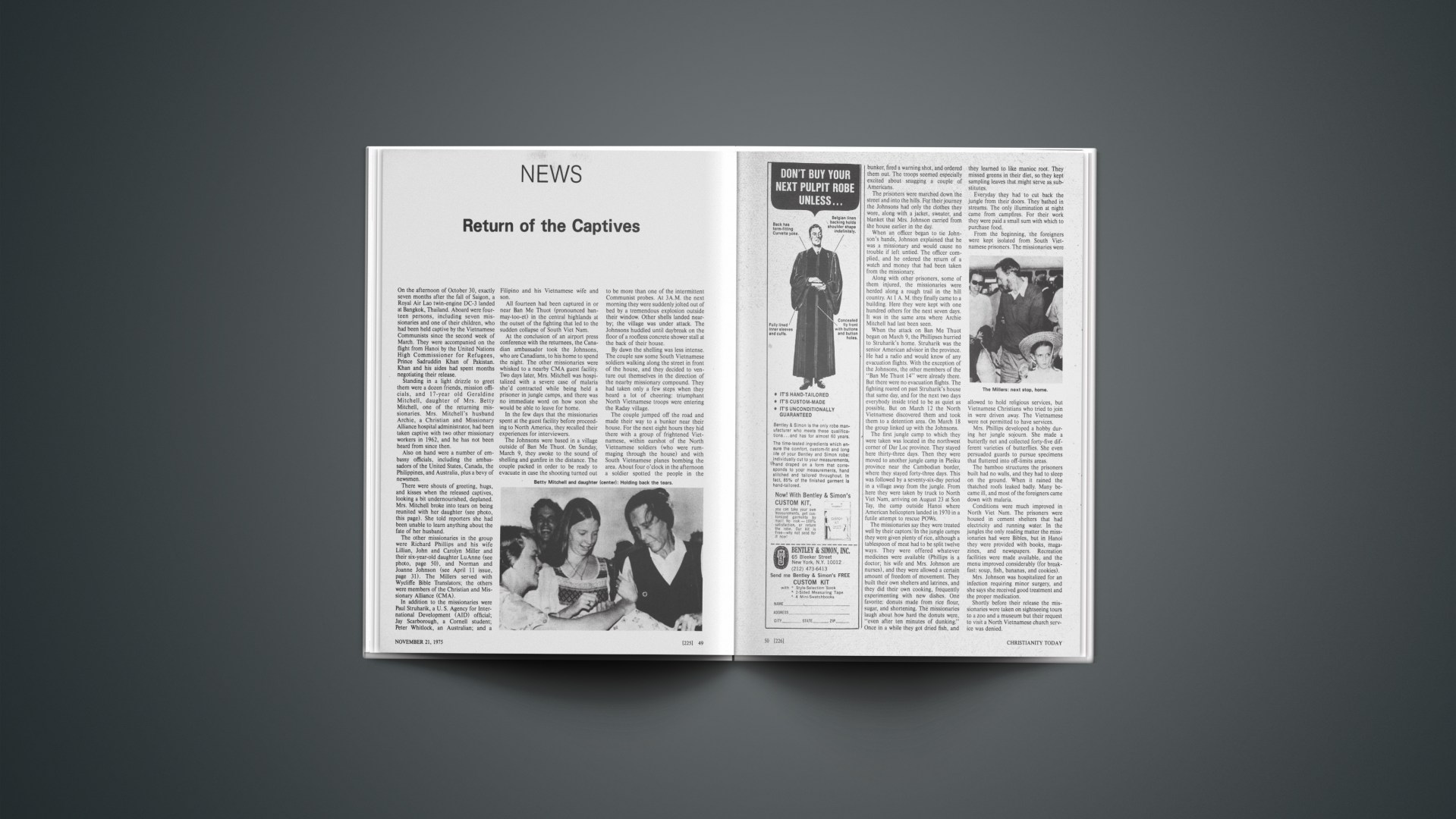

There were shouts of greeting, hugs, and kisses when the released captives, looking a bit undernourished, deplaned. Mrs. Mitchell broke into tears on being reunited with her daughter (see photo, this page). She told reporters she had been unable to learn anything about, the fate of her husband.

The other missionaries in the group were Richard Phillips and his wife Lillian, John and Carolyn Miller and their six-year-old daughter LuAnne (see photo, page 50), and Norman and Joanne Johnson (see April 11 issue, page 31). The Millers served with Wycliffe Bible Translators; the others were members of the Christian and Missionary Alliance (CMA).

In addition to the missionaries were Paul Struharik, a U. S. Agency for International Development (AID) official; Jay Scarborough, a Cornell student; Peter Whitlock, an Australian; and a Filipino and his Vietnamese wife and son.

All fourteen had been captured in or near Ban Me Thuot (pronounced ban-may-too-et) in the central highlands at the outset of the fighting that led to the sudden collapse of South Viet Nam.

At the conclusion of an airport press conference with the returnees, the Canadian ambassador took the Johnsons, who are Canadians, to his home to spend the night. The other missionaries were whisked to a nearby CMA guest facility. Two days later, Mrs. Mitchell was hospitalized with a severe case of malaria she’d contracted while being held a prisoner in jungle camps, and there was no immediate word on how soon she would be able to leave for home.

In the few days that the missionaries spent at the guest facility before proceeding to North America, they recalled their experiences for interviewers.

The Johnsons were based in a village outside of Ban Me Thuot. On Sunday, March 9, they awoke to the sound of shelling and gunfire in the distance. The couple packed in order to be ready to evacuate in case the shooting turned out to be more than one of the intermittent Communist probes. At 3A.M. the next morning they were suddenly jolted out of bed by a tremendous explosion outside their window. Other shells landed nearby; the village was under attack. The Johnsons huddled until daybreak on the floor of a roofless concrete shower stall at the back of their house.

By dawn the shelling was less intense. The couple saw some South Vietnamese soldiers walking along the street in front of the house, and they decided to venture out themselves in the direction of the nearby missionary compound. They had taken only a few steps when they heard a lot of cheering: triumphant North Vietnamese troops were entering the Raday village.

The couple jumped off the road and made their way to a bunker near their house. For the next eight hours they hid there with a group of frightened Vietnamese, within earshot of the North Vietnamese soldiers (who were rummaging through the house) and with South Vietnamese planes bombing the area. About four o’clock in the afternoon a soldier spotted the people in the bunker, fired a warning shot, and ordered them out. The troops seemed especially excited about snagging a couple of Americans.

The prisoners were marched down the street and into the hills. For their journey the Johnsons had only the clothes they wore, along with a jacket, sweater, and blanket that Mrs. Johnson carried from the house earlier in the day.

When an officer began to tie Johnson’s hands, Johnson explained that he was a missionary and would cause no trouble if left untied. The officer complied, and he ordered the return of a watch and money that had been taken from the missionary.

Along with other prisoners, some of them injured, the missionaries were herded along a rough trail in the hill country. At 1 A. M. they finally came to a building. Here they were kept with one hundred others for the next seven days. It was in the same area where Archie Mitchell had last been seen.

When the attack on Ban Me Thuot began on March 9, the Phillipses hurried to Struharik’s home. Struharik was the senior American advisor in the province. He had a radio and would know of any evacuation flights. With the exception of the Johnsons, the other members of the “Ban Me Thuot 14” were already there. But there were no evacuation flights. The fighting roared on past Struharik’s house that same day, and for the next two days everybody inside tried to be as quiet as possible. But on March 12 the North Vietnamese discovered them and took them to a detention area. On March 18 the group linked up with the Johnsons.

The first jungle camp to which they were taken was located in the northwest corner of Dar Loc province. They stayed here thirty-three days. Then they were moved to another jungle camp in Pleiku province near the Cambodian border, where they stayed forty-three days. This was followed by a seventy-six-day period in a village away from the jungle. From here they were taken by truck to North Viet Nam, arriving on August 23 at Son Tay, the camp outside Hanoi where American helicopters landed in 1970 in a futile attempt to rescue POWs.

The missionaries say they were treated well by their captors. In the jungle camps they were given plenty of rice, although a tablespoon of meat had to be split twelve ways. They were offered whatever medicines were available (Phillips is a doctor; his wife and Mrs. Johnson are nurses), and they were allowed a certain amount of freedom of movement. They built their own shelters and latrines, and they did their own cooking, frequently experimenting with new dishes. One favorite: donuts made from rice flour, sugar, and shortening. The missionaries laugh about how hard the donuts were, “even after ten minutes of dunking.” Once in a while they got dried fish, and they learned to like manioc root. They missed greens in their diet, so they kept sampling leaves that might serve as substitutes.

Everyday they had to cut back the jungle from their doors. They bathed in streams. The only illumination at night came from campfires. For their work they were paid a small sum with which to purchase food.

From the beginning, the foreigners were kept isolated from South Vietnamese prisoners. The missionaries were allowed to hold religious services, but Vietnamese Christians who tried to join in were driven away. The Vietnamese were not permitted to have services.

Mrs. Phillips developed a hobby during her jungle sojourn. She made a butterfly net and collected forty-five different varieties of butterflies. She even persuaded guards to pursue specimens that fluttered into off-limits areas.

The bamboo structures the prisoners built had no walls, and they had to sleep on the ground. When it rained the thatched roofs leaked badly. Many became ill, and most of the foreigners came down with malaria.

Conditions were much improved in North Viet Nam. The prisoners were housed in cement shelters that had electricity and running water. In the jungles the only reading matter the missionaries had were Bibles, but in Hanoi they were provided with books, magazines, and newspapers. Recreation facilities were made available, and the menu improved considerably (for breakfast: soup, fish, bananas, and cookies).

Mrs. Johnson was hospitalized for an infection requiring minor surgery, and she says she received good treatment and the proper medication.

Shortly before their release the missionaries were taken on sightseeing tours to a zoo and a museum but their request to visit a North Vietnamese church service was denied.

Throughout their captivity they were often subjected to tough interrogation sessions. Their questioners kept asking who they really were and why they really were in Viet Nam. Contrary to some speculation, the missionaries say they saw no atrocities, mass graves, or the like that might account for the North Vietnamese reluctance to release them sooner.

“They kept telling us that they had to wait for good relationships to develop between our countries and that they had to find out who we really were,” says Phillips.

Johnson complains that the North Vietnamese would not let him communicate with Canadian officials.

The missionaries, homesick for their families, at the encouragement of prison authorities wrote a number of letters to their children and other relatives, and Phillips prepared a tape for his family. He discovered after his release that none had been received.

They were required to attend indoctrination classes, but with the right questions and reasoning techniques the missionaries were able to turn some of these into witness sessions.

They held services on Sunday mornings in North Viet Nam. These consisted of some hymns, a Scripture reading, and a Bible message. There were regularly scheduled prayer meetings, and whenever anyone was in the interrogation room or was feeling especially low the others would all pray.

The missionaries say they were conscious of the prayers of people back home. “We want to thank everyone who prayed for us,” Mrs. Johnson told a broadcast interviewer. “That’s what brought us through.”

Canada: A Win For Women

After hours of debate, bishops of the 1.5-million-member Anglican Church of Canada voted 31–3 to give individual bishops power to admit qualified women to the priesthood after November 1, 1976. Meeting in Winnipeg, they asked Archbishop Edward Scott, the Canadian primate, to seek comments on their new policy from Anglican churches in other countries. Only “overwhelmingly negative” reaction could stall the move, but Scott anticipates no such reaction. The vote ratifies a move of the General Synod of the church last year.

A Church of England spokesman said it was unlikely that his church would object to the Canadian action. The English church decided in principle some time ago that it has no fundamental objection to women priests. The issue is now being considered by the Church of England bishops.

The decision was made despite several formidable attempts to block it. Some critics wanted to forestall action until the council’s next meeting. Others urged no action until after the 1978 Lambeth conference, which brings together Anglican and Episcopal bishops worldwide, but supporters saw such action as an “intolerable strain.” Reports have suggested that the purpose of a September visit to Canada by Presiding Bishop John N. Allin and eight provincial bishops of the Episcopal Church in the United States was to urge Canadian Anglicans to delay a decision. What effect the Canadian action will prove on the American scene is still a matter of speculation.

About 350 of Canada’s 2,700 Anglican clergy have signed a manifesto that calls for a total boycott against the ministry of any woman who accepts ordination. The manifesto states that “it is an impossibility in the divine economy for a woman to be a priest.”

The 1,000-member Council for the Faith, an alliance of Anglo-Catholics and evangelicals, described ordination of women as “schismatic if not heretical.” Some members of the council have threatened to quit the church to form a new Anglican church.

Archbishop Scott hopes that women candidates for the priesthood will be ordained next year at the same time as men wherever possible.

LESLIE K. TARR

Harvest Time On Taiwan

It was harvesting time as well as watering time in Taiwan early this month when evangelist Billy Graham ended a five-day crusade, breaking all records for a religious event on the 300-mile-long “island beautiful.”

The water was both spiritual and physical in Taipei, capital of the Republic of China. Rain fell each day, turning the playing field of the city stadium into a morass. People came from all over the island, however, sometimes huddling under umbrellas and sometimes squatting on styrofoam squares.

Only on the fourth night did the rain stop briefly, and the estimated 65,000 then filling every space in the stadium broke an attendance record for the facility. It was a special kind of victory for island evangelicals since ecumenical forces had predicted about six months earlier that the government would not allow a crusade in the stadium. On the final day, Graham preached to 60,000 in the rain on Noah, “the man who dared to stand alone.” In the audience was the top man in the government, Chiang Ching-kuo, premier and son of the late president Chiang Kai-shek.

Absent, but sending cabled greetings, was Madame Chiang Kai-shek, honorary chairman of the crusade. She was in the United States for medical attention. Her personal chaplain, Chow Lien-hwa, translated Graham’s messages into Mandarin Chinese. (Translation was also provided in Japanese and Taiwanese.)

Cumulative attendance for the five meetings was estimated at 250,000. Many of the listeners came from outlying towns and villages on the mountainous island, and Taipei churches provided sleeping space for thousands of visitors.

The harvest came as Graham issued an invitation at the end of each service. More than 11,500 decisions were recorded during the five days.

Graham’s team musicians were on hand, but the wet weather had the effect of making the music more Asian than American. Area instrumentalists and vocalists stepped in to lead when rainfall made it impossible to play the piano and organ.

A 5,000-voice choir was only one of the groups of volunteers recruited by local churches to assist. The 300 supporting congregations of some forty denominations also provided more than 3,000 counselors and 2,000 ushers.

A veteran Presbyterian pastor, C. C. Chen, was crusade chairman. “This is the biggest thing I have seen happen in the church life of Taiwan,” he said of the cooperative effort. “It is with deep thanksgiving and joy that I have watched us come together to save our brothers’ souls.”

A school of evangelism conducted in connection with the crusade attracted 2,900 pastors, pastors’ wives, and college and seminary students. Among those enrolled were 160 students, virtually the entire student body, of a seminary at Tainan. They rode eleven hours on a steam-powered train to attend.

China-born Ruth Graham, the evangelist’s wife, accompanied him to the Far East, where he was to conduct a crusade in Hong Kong two weeks after the Taipei meetings. Correspondent Nell Kennedy reported that the Grahams planned to meet in Tokyo with U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger, prompting speculation that they were arranging for a visit to Mrs. Graham’s childhood home in Mainland China.

Rio In Retrospect

Evangelicals in the Rio de Janeiro area staged an anniversary commemoration a year after Billy Graham’s crusade in famous Maracana Stadium, and an estimated 10,000 came through a downpour of rain to attend. It was still pouring at the end of the sermon, but some 500 came forward for counseling when the invitation was given.

Sponsors said that live radio broadcasting of the service gave additional thousands an excuse to stay home in the bad weather. They also emphasize that the Rio meeting is just one of many indications of the impact made on all of Brazil by the 1974 Graham campaign.

Graham biographer John Pollock of Britain was in the country to assess the impact a year later, and he reported that the crusade “set in motion a great surge of evangelistic activity, not just in greater Rio but wherever School of Evangelism students returned.” The “school” was a seminar series for Christian workers.

Among the places Pollock visited were the cities of Recife and Belem in the north and Brasilia and Belo Horizonte in the south. He says he found unprecedented cooperation among evangelicals and record response to their evangelistic endeavors.

Perhaps most important of Pollock’s discoveries was what he described as a new respect for the Gospel throughout the country. He attributed this mostly to the network telecast of the final Sunday rally of the 1974 crusade. It went into all major cities and into most states. Viewers saw a record crowd at Maracana.

Organizers reported to Pollock that decisions for Christ are still being recorded, and that initial inquiries are still coming to the phone number set up in October, 1974. More than 50,000 inquiries have been noted.

The crusade, its preparatory work, and its aftermath have “demolished the inferiority complex” of Brazilian evangelicals, Pollock found. He also attributed to the campaign these results: seminary enrollments in the Rio area are up to capacity and beyond; Baptists have met their national budget early; sales of evangelical literature are up, with one Rio bookshop experiencing a 50 per cent increase this year. The biographer also found that since Graham’s meetings evangelicals have made historic penetrations into intellectual and political circles.

The sense of achievement realized by the cooperating Christians also taught them they can work together “without having to unite in formal organization,” Pollock was told.