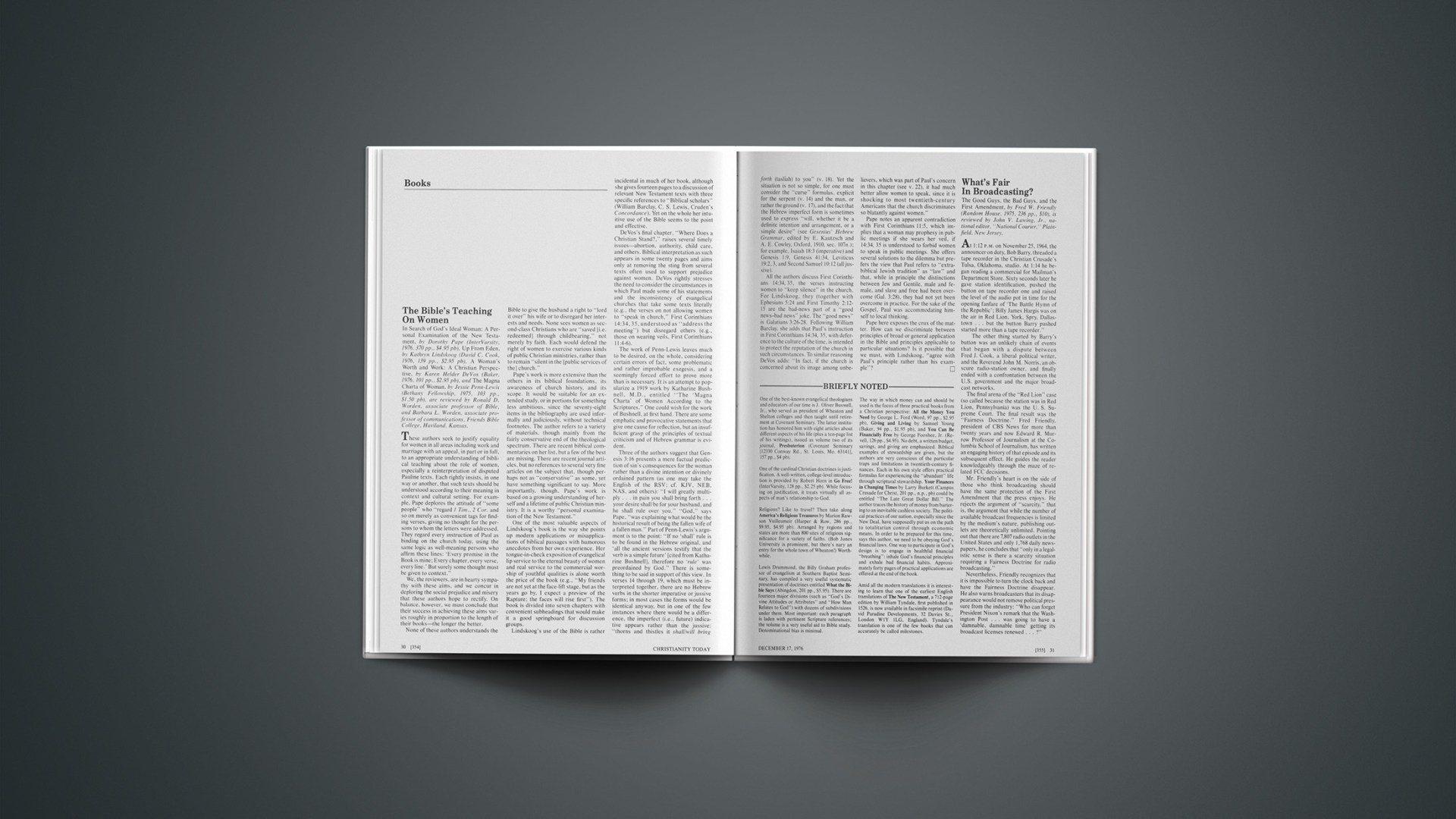

The Bible’S Teaching On Women

In Search of God’s Ideal Woman: A Personal Examination of the New Testament, by Dorothy Pape (InterVarsity, 1976, 370 pp., $4.95 pb), Up From Eden, by Kathryn Lindskoog (David C. Cook, 1976, 139 pp., $2.95 pb), A Woman’s Worth and Work: A Christian Perspective, by Karen Helder DeVos (Baker, 1976, 101 pp., $2.95 pb), and The Magna Charta of Woman, by Jessie Penn-Lewis (Bethany Fellowship, 1975, 103 pp., $1.50 pb), are reviewed by Ronald D. Worden, associate professor of Bible, and Barbara L. Worden, associate professor of communications, Friends Bible College, Haviland, Kansas.

These authors seek to justify equality for women in all areas including work and marriage with an appeal, in part or in full, to an appropriate understanding of biblical teaching about the role of women, especially a reinterpretation of disputed Pauline texts. Each rightly insists, in one way or another, that such texts should be understood according to their meaning in context and cultural setting. For example, Pape deplores the attitude of “some people” who “regard 1 Tim., 2 Cor. and so on merely as convenient tags for finding verses, giving no thought for the persons to whom the letters were addressed. They regard every instruction of Paul as binding on the church today, using the same logic as well-meaning persons who affirm these lines: ‘Every promise in the Book is mine; Every chapter, every verse, every line.’ But surely some thought must be given to context.”

We, the reviewers, are in hearty sympathy with these aims, and we concur in deploring the social prejudice and misery that these authors hope to rectify. On balance, however, we must conclude that their success in achieving these aims varies roughly in proportion to the length of their books—the longer the better.

None of these authors understands the Bible to give the husband a right to “lord it over” his wife or to disregard her interests and needs. None sees women as second-class Christians who are “saved [i.e. redeemed] through childbearing,” not merely by faith. Each would defend the right of women to exercise various kinds of public Christian ministries, rather than to remain “silent in the [public services of the] church.”

Pape’s work is more extensive than the others in its biblical foundations, its awareness of church history, and its scope. It would be suitable for an extended study, or in portions for something less ambitious, since the seventy-eight items in the bibliography are used informally and judiciously, without technical footnotes. The author refers to a variety of materials, though mainly from the fairly conservative end of the theological spectrum. There are recent biblical commentaries on her list, but a few of the best are missing. There are recent journal articles, but no references to several very fine articles on the subject that, though perhaps not as “conservative” as some, yet have something significant to say. More importantly, though, Pape’s work is based on a growing understanding of herself and a lifetime of public Christian ministry. It is a worthy “personal examination of the New Testament.”

One of the most valuable aspects of Lindskoog’s book is the way she points up modern applications or misapplications of biblical passages with humorous anecdotes from her own experience. Her tongue-in-check exposition of evangelical lip service to the eternal beauty of women and real service to the commercial worship of youthful qualities is alone worth the price of the book (e.g., “My friends are not yet at the face-lift stage, but as the years go by, I expect a preview of the Rapture; the faces will rise first”). The book is divided into seven chapters with convenient subheadings that would make it a good springboard for discussion groups.

Lindskoog’s use of the Bible is rather incidental in much of her book, although she gives fourteen pages to a discussion of relevant New Testament texts with three specific references to “Biblical scholars” (William Barclay, C. S. Lewis, Cruden’s Concordance). Yet on the whole her intuitive use of the Bible seems to the point and effective.

DeVos’s final chapter, “Where Does a Christian Stand?,” raises several timely issues—abortion, authority, child care, and others. Biblical interpretation as such appears in some twenty pages and aims only at removing the sting from several texts often used to support prejudice against women. DeVos rightly stresses the need to consider the circumstances in which Paul made some of his statements and the inconsistency of evangelical churches that take some texts literally (e.g., the verses on not allowing women to “speak in church,” First Corinthians 14:34, 35. understood as “address the meeting”) but disregard others (e.g., those on wearing veils, First Corinthians 11:4–6).

The work of Penn-Lewis leaves much to be desired, on the whole, considering certain errors of fact, some problematic and rather improbable exegesis, and a seemingly forced effort to prove more than is necessary. It is an attempt to popularize a 1919 work by Katharine Bushnell, M.D., entitled “The ‘Magna Charta’ of Women According to the Scriptures.” One could wish for the work of Bushnell, at first hand. There are some emphatic and provocative statements that give one cause for reflection, but an insufficient grasp of the principles of textual criticism and of Hebrew grammar is evident.

Three of the authors suggest that Genesis 3:16 presents a mere factual prediction of sin’s consequences for the woman rather than a divine intention or divinely ordained pattern (as one may take the English of the RSV; cf. KJV, NEB, NAS, and others): “I will greatly multiply … in pain you shall bring forth … your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” “God,” says Pape, “was explaining what would be the historical result of being the fallen wife of a fallen man.” Part of Penn-Lewis’s argument is to the point: “If no ‘shall’ rule is to be found in the Hebrew original, and ‘all the ancient versions testify that the verb is a simple future’ [cited from Katharine Bushnell], therefore no ‘rule’ was preordained by God.” There is something to be said in support of this view. In verses 14 through 19, which must be interpreted together, there are no Hebrew verbs in the shorter imperative or jussive forms; in most cases the forms would be identical anyway, but in one of the few instances where there would be a difference, the imperfect (i.e., future) indicative appears rather than the jussive: “thorns and thistles it shall/will bring forth (taslîah) to you” (v. 18). Yet the situation is not so simple, for one must consider the “curse” formulas, explicit for the serpent (v. 14) and the man, or rather the ground (v. 17), and the fact that the Hebrew imperfect form is sometimes used to express “will, whether it be a definite intention and arrangement, or a simple desire” (see Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar, edited by E. Kautzsch and A. E. Cowley, Oxford, 1910, sec. 107n.); for example, Isaiah 18:3 (imperative) and Genesis 1:9; Genesis 41:34; Leviticus 19:2, 3, and Second Samuel 10:12 (all jussive).

All the authors discuss First Corinthians 14:34, 35, the verses instructing women to “keep silence” in the church. For Lindskoog, they (together with Ephesians 5:24 and First Timothy 2:12–15 are the bad-news part of a “good news-bad news” joke. The “good news” is Galatians 3:26–28. Following William Barclay, she adds that Paul’s instruction in First Corinthians 14:34, 35, with deference to the culture of the time, is intended to protect the reputation of the church in such circumstances. To similar reasoning DeVos adds: “In fact, if the church is concerned about its image among unbelievers, which was part of Paul’s concern in this chapter (see v. 22), it had much better allow women to speak, since it is shocking to most twentieth-century Americans that the church discriminates so blatantly against women.”

Pape notes an apparent contradiction with First Corinthians 11:5, which implies that a woman may prophesy in public meetings if she wears her veil, if 14:34, 35 is understood to forbid women to speak in public meetings. She offers several solutions to the dilemma but prefers the view that Paul refers to “extra-biblical Jewish tradition” as “law” and that, while in principle the distinctions between Jew and Gentile, male and female, and slave and free had been overcome (Gal. 3:28), they had not yet been overcome in practice. For the sake of the Gospel, Paul was accommodating himself to local thinking.

Pape here exposes the crux of the matter. How can we discriminate between principles of broad or general application in the Bible and principles applicable to particular situations? Is it possible that we must, with Lindskoog, “agree with Paul’s principle rather than his example”?

Briefly Noted

One of the best-known evangelical theologians and educators of our time is J. Oliver Buswell, Jr., who served as president of Wheaton and Shelton colleges and then taught until retirement at Covenant Seminary. The latter institution has honored him with eight articles about different aspects of his life (plus a ten-page list of his writings), issued as volume two of its journal, Presbuterion (Covenant Seminary [12330 Conway Rd., St. Louis, Mo. 63141], 157 pp., $4 pb).

One of the cardinal Christian doctrines is justification. A well-written, college-level introduction is provided by Robert Horn in Go Free! (InterVarsity, 128 pp., $2.25 pb). While focusing on justification, it treats virtually all aspects of man’s relationship to God.

Religious? Like to travel? Then take along America’s Religious Treasures by Marion Rawson Vuilleumeir (Harper & Row, 286 pp., $9.95, $4.95 pb). Arranged by regions and states are more than 800 sites of religious significance for a variety of faiths. (Bob Jones University is prominent, but there’s nary an entry for the whole town of Wheaton!) Worthwhile.

Lewis Drummond, the Billy Graham professor of evangelism at Southern Baptist Seminary, has compiled a very useful systematic presentation of doctrines entitled What the Bible Says (Abingdon, 201 pp., $5.95). There are fourteen major divisions (such as “God’s Divine Attitudes or Attributes” and “How Man Relates to God”) with dozens of subdivisions under them. Most important: each paragraph is laden with pertinent Scripture references; the volume is a very useful aid to Bible study. Denominational bias is minimal.

The way in which money can and should be used is the focus of three practical books from a Christian perspective: All the Money You Need by George L. Ford (Word, 97 pp., $2.95 pb), Giving and Living by Samuel Young (Baker, 94 pp., $1.95 pb), and You Can Be Financially Free by George Fooshee, Jr. (Revell, 126 pp., $4.95). No debt, a written budget, savings, and giving are emphasized. Biblical examples of stewardship are given, but the authors are very conscious of the particular traps and limitations in twentieth-century finances. Each in his own style offers practical formulas for experiencing the “abundant” life through scriptural stewardship. Your Finances in Changing Times by Larry Burkett (Campus Crusade for Christ, 201 pp., n.p., pb) could be entitled “The Late Great Dollar Bill.” The author traces the history of money from bartering to an inevitable cashless society. The political practices of our nation, especially since the New Deal, have supposedly put us on the path to totalitarian control through economic means. In order to be prepared for this time, says this author, we need to be obeying God’s financial laws. One way to participate in God’s design is to engage in healthful financial “breathing”: inhale God’s financial principles and exhale bad financial habits. Approximately forty pages of practical applications are offered at the end of the book.

Amid all the modern translations it is interesting to learn that one of the earliest English translations of The New Testament, a 712-page edition by William Tyndale, first published in 1526, is now available in facsimile reprint (David Paradine Developments, 32 Davies St., London W1Y 1LG, England). Tyndale’s translation is one of the few books that can accurately be called milestones.

What’S Fair In Broadcasting?

The Good Guys, the Bad Guys, and the First Amendment, by Fred W. Friendly (Random House, 1975, 236 pp., $10), is reviewed by John V. Lawing, Jr., national editor, “National Courier,” Plainfield, New Jersey.

At 1:12 P.M. on November 25, 1964, the announcer on duty, Bob Barry, threaded a tape recorder in the Christian Crusade’s Tulsa, Oklahoma, studio. At 1:14 he began reading a commercial for Mailman’s Department Store. Sixty seconds later he gave station identification, pushed the button on tape recorder one and raised the level of the audio pot in time for the opening fanfare of ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’; Billy James Hargis was on the air in Red Lion, York, Spry, Dallastown … but the button Barry pushed started more than a tape recorder.”

The other thing started by Barry’s button was an unlikely chain of events that began with a dispute between Fred J. Cook, a liberal political writer, and the Reverend John M. Norris, an obscure radio-station owner, and finally ended with a confrontation between the U.S. government and the major broadcast networks.

The final arena of the “Red Lion” case (so called because the station was in Red Lion, Pennsylvania) was the U. S. Supreme Court. The final result was the “Fairness Doctrine.” Fred Friendly, president of CBS News for more than twenty years and now Edward R. Murrow Professor of Journalism at the Columbia School of Journalism, has written an engaging history of that episode and its subsequent effect. He guides the reader knowledgeably through the maze of related FCC decisions.

Mr. Friendly’s heart is on the side of those who think broadcasting should have the same protection of the First Amendment that the press enjoys. He rejects the argument of “scarcity,” that is, the argument that while the number of available broadcast frequencies is limited by the medium’s nature, publishing outlets are theoretically unlimited. Pointing out that there are 7,807 radio outlets in the United States and only 1,768 daily newspapers, he concludes that “only in a legalistic sense is there a scarcity situation requiring a Fairness Doctrine for radio broadcasting.”

Nevertheless, Friendly recognizes that it is impossible to turn the clock back and have the Fairness Doctrine disappear. He also warns broadcasters that its disappearance would not remove political pressure from the industry: “Who can forget President Nixon’s remark that the Washington Post … was going to have a ‘damnable, damnable time’ getting its broadcast licenses renewed …?”

The professor calls on the FCC to institute a policy that will encourage stations to “invent formats for handling opposing viewpoints as a part of their regular programming,” a policy that will look at a station’s entire output and not one aspect. And he calls on broadcasters to provide a forum for dissent voluntarily as a part of their responsibility.

The book is fascinating reading for anyone and necessary reading for everyone in any way involved in broadcasting.

Waiting On God

The Genesee Diary: Report From a Trappist Monastery, by Henri M. Nouwen (Doubleday, 1976, 200 pp., $6.95), is reviewed by Noel Buchanan, religion writer, “The Lethbridge Herald,” Lethbridge, Alberta.

Standing on a quiet little beach in Waterton National Park, Alberta, recently, I was overwhelmed by the magnificent view of mountains and the lake. The familiar words of the hymn “How Great Thou Art” flooded my mind, and I very definitely felt, as I stood there physically alone, a strong arm reach across my back and hug me.

Henri Nouwen, a Dutch Jesuit, speaks of a similar awareness of God’s presence in his life in a personal diary published after he spent seven months at the Abbey of the Genesee in upstate New York.

“Just as a whole world of beauty can be discovered in one flower, so the great grace of God can be tasted in one small moment. Just as no great travels are necessary to see the beauty of creation, so no great ecstasies are needed to discover the love of God. But you have to be still and wait so that you realize that God is not in the earthquake, the storm, or the lightning, but in the gentle breeze with which He touches your back,” Father Nouwen writes. And throughout his diary, God touches every quiet soul that is listening for him.

Others have attempted to write about retreats, about meeting God and being rejuvenated in an outdoor setting. But the human element is often too present in such accounts, and they leave your heart focused on what someone else has “experienced” rather than on God himself. Father Nouwen’s book is different; it will draw any Christian’s heart toward God and his Son.

This is an excellent practical report on day-to-day life in a contemplative setting. Father Nouwen explains the difference between being a teaching priest (his usual role at Yale Divinity School) and a monk. He tells how he battled for acceptance in the monastery, shaving his head and dressing like the monks. He writes about prayer, about gathering rocks for a new chapel, about washing raisins in the bakery, about his reaction to world political news received during the retreat.

The Genesee Diary is far and away one of the most rewarding books I have read in years, because it so beautifully lifts the heart and mind to God and the Saviour.

Help For A Pastoral Problem

The Problem Clergymen Don’t Talk About, by Charles L. Rassieur (Westminster, 1976, 157pp., $3.95), is reviewed by Cecil B. Murphey, pastor, Riverdale Presbyterian Church, Riverdale, Georgia.

The problem is, as you might have guessed, sexual attraction—the kind male ministers sometimes face when they counsel women. Rassieur wants to help clergymen “cope more effectively, more confidently, and with a sounder theological understanding when they are sexually attracted to a female counselee or parishioner.” His material comes from his own practice in pastoral care and from research interviews with parish pastors.

Rassieur doesn’t waste the reader’s time pondering the question, Can a pastor find himself sexually attracted to women parishioners? He accepts that as the foundation of his book. And he limits his discussion to male, heterosexual clergy.

How does a married pastor get involved with another woman? Rassieur handles this beautifully, and concludes that a man allows himself to get involved. He can’t plead helplessness. Rassieur insists that ministers must first claim responsibility for giving in to their sexual responses. The section called “The pastor deals with himself” is in my opinion the best one in the book.

And how does the minister cope with the counselee who attracts him? Tell her? Ignore his feelings? The author offers common-sense suggestions and then leads into a chapter on how the minister should deal with his wife. The concluding chapter is by Rassieur’s own wife, Ginni, who offers practical advice to both husbands and wives.

New Periodical

The Journal of the Association of Evangelical Institutional Chaplains was launched in July as an occasional publication for those interested in ministering to prisoners and others involved with the criminal-justice system. The first issue, forty-three pages, offers several useful articles (such as “Discipleship Training in a Jail”) and also a ten-page list of organizations that either minister to offenders or else offer services especially useful to such a ministry. This issue costs $3; an annual subscription is $5 (1036 S. Highland St., Arlington, Va. 22204). For all theological libraries.