On the weekend of April 3 the Romanian security police rounded up a number of dissidents who have been campaigning for human rights. Press reports from Paris said that novelist Paul Goma, 42, one of Romania’s leading writers, had been arrested in Bucharest and eight others sent to work camps for a year. They apparently were the architects of a human-rights appeal publicized earlier this year and subsequently signed by hundreds of other Romanians.

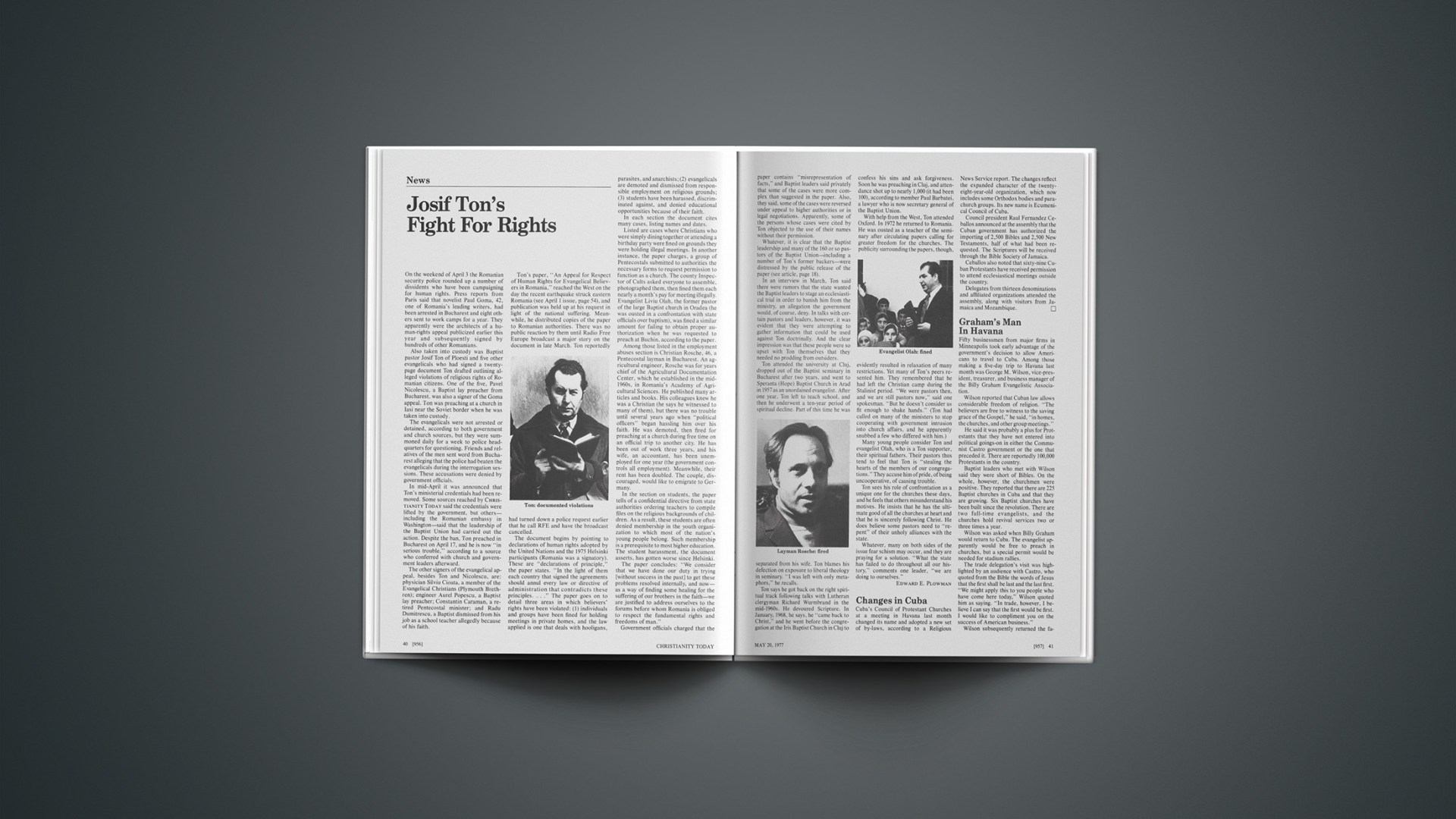

Also taken into custody was Baptist pastor Josif Ton of Ploesti and five other evangelicals who had signed a twenty-page document Ton drafted outlining alleged violations of religious rights of Romanian citizens. One of the five, Pavel Nicolescu, a Baptist lay preacher from Bucharest, was also a signer of the Goma appeal. Ton was preaching at a church in Iasi near the Soviet border when he was taken into custody.

The evangelicals were not arrested or detained, according to both government and church sources, but they were summoned daily for a week to police headquarters for questioning. Friends and relatives of the men sent word from Bucharest alleging that the police had beaten the evangelicals during the interrogation sessions. These accusations were denied by government officials.

In mid-April it was announced that Ton’s ministerial credentials had been removed. Some sources reached by CHRISTIANITY TODAY said the credentials were lifted by the government, but others—including the Romanian embassy in Washington—said that the leadership of the Baptist Union had carried out the action. Despite the ban, Ton preached in Bucharest on April 17, and he is now “in serious trouble,” according to a source who conferred with church and government leaders afterward.

The other signers of the evangelical appeal, besides Ton and Nicolescu, are: physician Silviu Cioata, a member of the Evangelical Christians (Plymouth Brethren); engineer Aurel Popescu, a Baptist lay preacher; Constantin Caraman, a retired Pentecostal minister; and Radu Dumitrescu, a Baptist dismissed from his job as a school teacher allegedly because of his faith.

Ton’s paper, “An Appeal for Respect of Human Rights for Evangelical Believers in Romania,” reached the West on the day the recent earthquake struck eastern Romania (see April 1 issue, page 54), and publication was held up at his request in light of the national suffering. Meanwhile, he distributed copies of the paper to Romanian authorities. There was no public reaction by them until Radio Free Europe broadcast a major story on the document in late March. Ton reportedly had turned down a police request earlier that he call RFE and have the broadcast cancelled.

The document begins by pointing to declarations of human rights adopted by the United Nations and the 1975 Helsinki participants (Romania was a signatory). These are “declarations of principle,” the paper states. “In the light of them each country that signed the agreements should annul every law or directive of administration that contradicts these principles.…” The paper goes on to detail three areas in which believers’ rights have been violated: (1) individuals and groups have been fined for holding meetings in private homes, and the law applied is one that deals with hooligans, parasites, and anarchists; (2) evangelicals are demoted and dismissed from responsible employment on religious grounds; (3) students have been harassed, discriminated against, and denied educational opportunities because of their faith.

In each section the document cites many cases, listing names and dates.

Listed are cases where Christians who were simply dining together or attending a birthday party were fined on grounds they were holding illegal meetings. In another instance, the paper charges, a group of Pentecostals submitted to authorities the necessary forms to request permission to function as a church. The county Inspector of Cults asked everyone to assemble, photographed them, then fined them each nearly a month’s pay for meeting illegally. Evangelist Liviu Olah, the former pastor of the large Baptist church in Oradea (he was ousted in a confrontation with state officials over baptism), was fined a similar amount for failing to obtain proper authorization when he was requested to preach at Buchin, according to the paper.

Among those listed in the employment abuses section is Christian Rosche, 46, a Pentecostal layman in Bucharest. An agricultural engineer, Rosche was for years chief of the Agricultural Documentation Center, which he established in the mid-1960s, in Romania’s Academy of Agricultural Sciences. He published many articles and books. His colleagues knew he was a Christian (he says he witnessed to many of them), but there was no trouble until several years ago when “political officers” began hassling him over his faith. He was demoted, then fired for preaching at a church during free time on an official trip to another city. He has been out of work three years, and his wife, an accountant, has been unemployed for one year (the government controls all employment). Meanwhile, their rent has been doubled. The couple, discouraged, would like to emigrate to Germany.

In the section on students, the paper tells of a confidential directive from state authorities ordering teachers to compile files on the religious backgrounds of children. As a result, these students are often denied membership in the youth organization to which most of the nation’s young people belong. Such membership is a prerequisite to most higher education. The student harassment, the document asserts, has gotten worse since Helsinki.

The paper concludes: “We consider that we have done our duty in trying [without success in the past] to get these problems resolved internally, and now—as a way of finding some healing for the suffering of our brothers in the faith—we are justified to address ourselves to the forums before whom Romania is obliged to respect the fundamental rights and freedoms of man.”

Government officials charged that the paper contains “misrepresentation of facts,” and Baptist leaders said privately that some of the cases were more complex than suggested in the paper. Also, they said, some of the cases were reversed under appeal to higher authorities or in legal negotiations. Apparently, some of the persons whose cases were cited by Ton objected to the use of their names without their permission.

Whatever, it is clear that the Baptist leadership and many of the 160 or so pastors of the Baptist Union—including a number of Ton’s former backers—were distressed by the public release of the paper (see article, page 18).

In an interview in March, Ton said there were rumors that the state wanted the Baptist leaders to stage an ecclesiastical trial in order to banish him from the ministry, an allegation the government would, of course, deny. In talks with certain pastors and leaders, however, it was evident that they were attempting to gather information that could be used against Ton doctrinally. And the clear impression was that these people were so upset with Ton themselves that they needed no prodding from outsiders.

Ton attended the university at Cluj, dropped out of the Baptist seminary in Bucharest after two years, and went to Speranta (Hope) Baptist Church in Arad in 1957 as an unordained evangelist. After one year, Ton left to teach school, and then he underwent a ten-year period of spiritual decline. Part of this time he was separated from his wife. Ton blames his defection on exposure to liberal theology in seminary. “I was left with only metaphors,” he recalls.

Ton says he got back on the right spiritual track following talks with Lutheran clergyman Richard Wurmbrand in the mid-1960s. He devoured Scripture. In January, 1968, he says, he “came back to Christ,” and he went before the congregation at the Iris Baptist Church in Cluj to confess his sins and ask forgiveness. Soon he was preaching in Cluj, and attendance shot up to nearly 1,000 (it had been 100), according to member Paul Barbatei, a lawyer who is now secretary general of the Baptist Union.

With help from the West, Ton attended Oxford. In 1972 he returned to Romania. He was ousted as a teacher of the seminary after circulating papers calling for greater freedom for the churches. The publicity surrounding the papers, though, evidently resulted in relaxation of many restrictions. Yet many of Ton’s peers resented him. They remembered that he had left the Christian camp during the Stalinist period. “We were pastors then, and we are still pastors now,” said one spokesman. “But he doesn’t consider us fit enough to shake hands.” (Ton had called on many of the ministers to stop cooperating with government intrusion into church affairs, and he apparently snubbed a few who differed with him.)

Many young people consider Ton and evangelist Olah, who is a Ton supporter, their spiritual fathers. Their pastors thus tend to feel that Ton is “stealing the hearts of the members of our congregations.” They accuse him of pride, of being uncooperative, of causing trouble.

Ton sees his role of confrontation as a unique one for the churches these days, and he feels that others misunderstand his motives. He insists that he has the ultimate good of all the churches at heart and that he is sincerely following Christ. He does believe some pastors need to “repent” of their unholy alliances with the state.

Whatever, many on both sides of the issue fear schism may occur, and they are praying for a solution. “What the state has failed to do throughout all our history,” comments one leader, “we are doing to ourselves.”

Changes in Cuba

Cuba’s Council of Protestant Churches at a meeting in Havana last month changed its name and adopted a new set of by-laws, according to a Religious News Service report. The changes reflect the expanded character of the twenty-eight-year-old organization, which now includes some Orthodox bodies and para-church groups. Its new name is Ecumenical Council of Cuba.

Council president Raul Fernandez Ceballos announced at the assembly that the Cuban government has authorized the importing of 2,500 Bibles and 2,500 New Testaments, half of what had been requested. The Scriptures will be received through the Bible Society of Jamaica.

Ceballos also noted that sixty-nine Cuban Protestants have received permission to attend ecclesiastical meetings outside the country.

Delegates from thirteen denominations and affiliated organizations attended the assembly, along with visitors from Jamaica and Mozambique.

Graham’s Man In Havana

Fifty businessmen from major firms in Minneapolis took early advantage of the government’s decision to allow Americans to travel to Cuba. Among those making a five-day trip to Havana last month was George M. Wilson, vice-president, treasurer, and business manager of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Wilson reported that Cuban law allows considerable freedom of religion. “The believers are free to witness to the saving grace of the Gospel,” he said, “in homes, the churches, and other group meetings.”

He said it was probably a plus for Protestants that they have not entered into political goings-on in either the Communist Castro government or the one that preceded it. There are reportedly 100,000 Protestants in the country.

Baptist leaders who met with Wilson said they were short of Bibles. On the whole, however, the churchmen were positive. They reported that there are 225 Baptist churches in Cuba and that they are growing. Six Baptist churches have been built since the revolution. There are two full-time evangelists, and the churches hold revival services two or three times a year.

Wilson was asked when Billy Graham would return to Cuba. The evangelist apparently would be free to preach in churches, but a special permit would be needed for stadium rallies.

The trade delegation’s visit was highlighted by an audience with Castro, who quoted from the Bible the words of Jesus that the first shall be last and the last first. “We might apply this to you people who have come here today,” Wilson quoted him as saying. “In trade, however, I believe I can say that the first would be first. I would like to compliment you on the success of American business.”

Wilson subsequently returned the favor by praising Cuban hospitality and quoting from Proverbs 24 from The Living Bible, “Any enterprise is built by wise planning, becomes strong through common sense, and profits wonderfully by keeping abreast of the facts.” Wilson added: “This we need to do in our future relations with you.”

Signals From Space

The Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) of Virginia Beach, Virginia, last month dedicated a $1 million satellite earth station and began daily religious broadcasting of radio and television programs by way of RCA’s SATCOM II satellite 22,000 miles away in space. The network said it had signed a $5.5 million, six-year contract with RCA to use the satellite for 47.5 hours a week now and for twenty-four hours a day by the middle of this summer.

Stations must have special reception equipment to receive the satellite transmission. Signals are beamed to SATCOM II and retransmitted to other earth stations and satellites, and then to television, radio, and cable television stations around the globe.

The dedication ceremonies, televised live via SATCOM II on April 29, were part of the International 700 Club, a popular CBN program seen or heard on four continents.

CBN is developing an international communications center in Virginia Beach that will provide counseling services, translation facilities, and communications training for students from Third World countries.

Meanwhile, the Southern Baptist Radio and Television Commission (SBRTC) dedicated debt-free its new $3.3 million television studio and training center in Fort Worth, Texas. The studio was described as the largest of its kind between New York and California. SBRTC has grown from four employees in 1955 to become the world’s largest producer of religious programs for radio and television, according to SBRTC spokesmen.

SBRTC president Paul M. Stevens declared during dedication ceremonies that the Christian world is entering a new era of electronic communication, signaling “the beginning of the greatest evangelistic effort in the world’s history.”

Episcopalians: Words of Caution

When Episcopal bishop Paul Moore of New York ordained Ellen M. Barrett, a self-proclaimed lesbian, to the priesthood last January, he touched off a controversy that overshadows in some sectors the debate over women’s ordination. Some parishes cut off denominational giving in protest. Late last month in a meeting at Louisville, the Executive Council of the Episcopal Church went on record expressing the “hope” that “no bishop will ordain or license any professing and practicing homosexual until the issue [is] resolved by the General Convention.” (The General Convention, which normally meets triennially, is the highest policymaking body in the church.)

Without specifically singling out homosexuality, the council also voted to “condemn all actions which offend the moral law of the church,” and to underscore the “necessity” for the church to give moral leadership in world affairs.

The council decried what it called “abuse” of Episcopal marriage canons (an issue apparently raised by the recent remarriage of Elizabeth Taylor by an Episcopal priest) and the “refusal of priests to honor the godly admonitions of their bishops.” The latter statement referred to dissident priests who refused to accept the 2.8 million-member denomination’s decision last fall to allow women to become priests. At least half a dozen priests have been suspended and charged with “abandoning the communion” of the Episcopal Church in their actions of dissent, it was reported.

Among those suspended is Canon Albert J. duBois, executive director of Anglicans United and for twenty-four years executive director of American Church Union, an Anglo-Catholic (“high church”) faction within the Episcopal Church. Anglicans United was formed to fight against acceptance of women priests and a new prayer book at last year’s General Convention.

The diocese of Long Island informed duBois in April that he will be deposed from the ministry in six months. One of the charges against him is that he is attempting to form a new denomination through Anglicans United, but DuBois denies having participated in any such plans. Yet AU announcements have indicated it intends to form a new church body, complete with bishops, to carry on as the “true” Episcopal Church. A convention to form the new body is set for St. Louis in September. Retired bishop Albert A. Chambers of the diocese of Springfield, Illinois, last month succeeded duBois as international president of Anglicans United.

In California, Rector Robert Morse of St. Peter’s Church in Oakland, was suspended and threatened with defrocking by Bishop C. Kilmer Myers after Morse’s congregation voted overwhelmingly to break with the national church over the women’s-ordination issue. Defrocking, cautioned Myers, would be honored by the Archbishop of Canterbury, spiritual leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The implication is that the traditionalist Episcopal body Morse, duBois, and others want to organize will not be recognized as part of the Anglican fellowship.