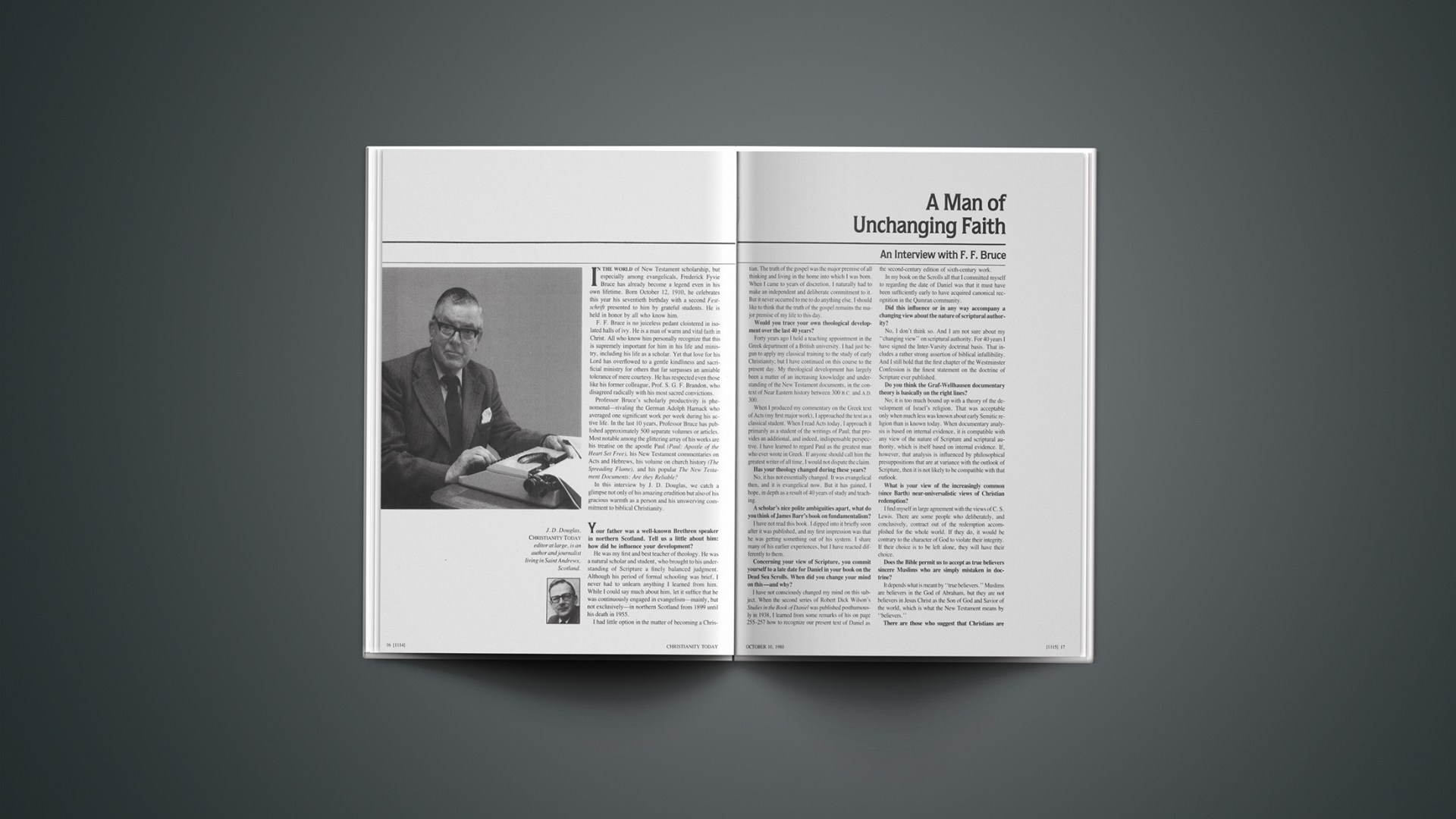

In the world of New Testament scholarship, but especially among evangelicals, Frederick Fyvie Bruce has already become a legend even in his own lifetime. Born October 12, 1910, he celebrates this year his seventieth birthday with a second Festschrift presented to him by grateful students. He is held in honor by all who know him.

F. F. Bruce is no juiceless pedant cloistered in isolated halls of ivy. He is a man of warm and vital faith in Christ. All who know him personally recognize that this is supremely important for him in his life and ministry, including his life as a scholar. Yet that love for his Lord has overflowed to a gentle kindliness and sacrificial ministry for others that far surpasses an amiable tolerance of mere courtesy. He has respected even those like his former colleague, Prof. S. G. F. Brandon, who disagreed radically with his most sacred convictions.

Professor Bruce’s scholarly productivity is phenomenal—rivaling the German Adolph Harnack who averaged one significant work per week during his active life. In the last 10 years, Professor Bruce has published approximately 500 separate volumes or articles. Most notable among the glittering array of his works are his treatise on the apostle Paul (Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free), his New Testament commentaries on Acts and Hebrews, his volume on church history (The Spreading Flame), and his popular The New Testament Documents: Are they Reliable?

In this interview by J. D. Douglas, we catch a glimpse not only of his amazing erudition but also of his gracious warmth as a person and his unswerving commitment to biblical Christianity.

Your father was a well-known Brethren speaker in northern Scotland. Tell us a little about him: how did he influence your development?

He was my first and best teacher of theology. He was a natural scholar and student, who brought to his understanding of Scripture a finely balanced judgment. Although his period of formal schooling was brief, I never had to unlearn anything I learned from him. While I could say much about him, let it suffice that he was continuously engaged in evangelism—mainly, but not exclusively—in northern Scotland from 1899 until his death in 1955.

I had little option in the matter of becoming a Christian. The truth of the gospel was the major premise of all thinking and living in the home into which I was born. When I came to years of discretion, I naturally had to make an independent and deliberate commitment to it. But it never occurred to me to do anything else. I should like to think that the truth of the gospel remains the major premise of my life to this day.

Would you trace your own theological development over the last 40 years?

Forty years ago I held a teaching appointment in the Greek department of a British university. I had just begun to apply my classical training to the study of early Christianity; but I have continued on this course to the present day. My theological development has largely been a matter of an increasing knowledge and understanding of the New Testament documents, in the context of Near Eastern history between 300 B.C. and A.D. 300.

When I produced my commentary on the Greek text of Acts (my first major work), I approached the text as a classical student. When I read Acts today, I approach it primarily as a student of the writings of Paul; that provides an additional, and indeed, indispensable perspective. I have learned to regard Paul as the greatest man who ever wrote in Greek. If anyone should call him the greatest writer of all time, I would not dispute the claim.

Has your theology changed during these years?

No, it has not essentially changed. It was evangelical then, and it is evangelical now. But it has gained, I hope, in depth as a result of 40 years of study and teaching.

A scholar’s nice polite ambiguities apart, what do you think of James Barr’s book on fundamentalism?

I have not read this book. I dipped into it briefly soon after it was published, and my first impression was that he was getting something out of his system. I share many of his earlier experiences, but I have reacted differently to them.

Concerning your view of Scripture, you commit yourself to a late date for Daniel in your book on the Dead Sea Scrolls. When did you change your mind on this—and why?

I have not consciously changed my mind on this subject. When the second series of Robert Dick Wilson’s Studies in the Book of Daniel was published posthumously in 1938, I learned from some remarks of his on page 255–257 how to recognize our present text of Daniel as the second-century edition of sixth-century work.

In my book on the Scrolls all that I committed myself to regarding the date of Daniel was that it must have been sufficiently early to have acquired canonical recognition in the Qumran community.

Did this influence or in any way accompany a changing view about the nature of scriptural authority?

No, I don’t think so. And I am not sure about my “changing view” on scriptural authority. For 40 years I have signed the Inter-Varsity doctrinal basis. That includes a rather strong assertion of biblical infallibility. And I still hold that the first chapter of the Westminster Confession is the finest statement on the doctrine of Scripture ever published.

Do you think the Graf-Wellhausen documentary theory is basically on the right lines?

No; it is too much bound up with a theory of the development of Israel’s religion. That was acceptable only when much less was known about early Semitic religion than is known today. When documentary analysis is based on internal evidence, it is compatible with any view of the nature of Scripture and scriptural authority, which is itself based on internal evidence. If, however, that analysis is influenced by philosophical presuppositions that are at variance with the outlook of Scripture, then it is not likely to be compatible with that outlook.

What is your view of the increasingly common (since Barth) near-universalistic views of Christian redemption?

I find myself in large agreement with the views of C. S. Lewis. There are some people who deliberately, and conclusively, contract out of the redemption accomplished for the whole world. If they do, it would be contrary to the character of God to violate their integrity. If their choice is to be left alone, they will have their choice.

Does the Bible permit us to accept as true believers sincere Muslims who are simply mistaken in doctrine?

It depends what is meant by “true believers.” Muslims are believers in the God of Abraham, but they are not believers in Jesus Christ as the Son of God and Savior of the world, which is what the New Testament means by “believers.”

There are those who suggest that Christians arepledged to preach Christ—not to combat one or another particular ideology.

That is true; our primary commitment is to preach Christ. But this will inevitably involve opposition to ideologies that are incompatible with the preaching of Christ.

What about the controversy over human rights?

The biblical view of God and man has greatest possible bearing on this. My paramount reason for respecting human rights is my belief in God the Father, who has created me and all mankind, and in Jesus Christ his Son, who has redeemed me and all mankind. Moreover, the biblical view of God and man teaches me to be as concerned about my own duties as I am about other people’s rights.

As you travel overseas, what encourages you most about churches in the world?

I am specially encouraged by the thoroughgoing commitment of so many young people to the cause of Christ. Although my travel does not take me much into the non-Western world, I see this in both the Western and non-Western world.

What advice would you give to a young man or woman about to begin teaching in a theological faculty?

Teach the fruit of your own study—not second-hand opinions, whether orthodox or unorthodox. And encourage your students to think for themselves and to form their own judgments on the acceptability or unacceptability of what you teach them.

There is an American religious encyclopedia that has slipped in a spoof entry in order to catch plagiarists. Have you found plagiarism to be widespread in the academic world?

No, not very widespread, although it crops up sometimes in, say, the lifting of references from other people’s works without verifying them. But the ease with which this practice can be detected is a check on it.

Have you found membership in the Christian Brethren to be a handicap in your academic career?

No; in no way.

Your fellow Scot, Prof. William Barclay, doubted whether his wife had ever read one of his books. He seemed to imply that this contributed to a happy marriage. Does this reflect Mrs. Bruce’s position?

No. She has read several of my books. In addition, she has helped to check the proofs and compile the indexes of some. This does not appear to have detracted from the happiness of our marriage.

Which of your books has given you the most satisfaction?

Probably Paul: Apostle of the Free Spirit, if I may call it by its proper title, the text of which has been corrupted in American transmission by subtitling it—presumably to avoid ambiguity—“Apostle of the Heart Set Free.”

Is it true that you are relinquishing the editorship of the Evangelical Quarterly after more than 30 years?

Yes; and I am delighted to pass on the job to my distinguished friend, Prof. Howard Marshall of Aberdeen University.

I know you are still busy. Could you tell us what you are working on at present?

I have practically finished the volume on Galatians for the New International Greek Commentary series. Then I plan to start on a similar work on Thessalonians for the new Word Commentary series.

In The English Bible (1961) you expressed a hope for more translations in “modern English.” Would you call a halt now—since we seem to have had a flurry of them in recent times?

Yes. We have enough versions now to satisfy all requirements and I can’t see what good purpose would be served by adding to them. I can’t keep up with all that we have.

Remembering your own training in what Matthew Arnold once called the “grand, old, fortifying, classical curriculum,” how do you regard the declining emphasis in schools on the teaching of Latin and Greek?

It leads to cultural impoverishment in more areas than one might imagine. Further, no civilization will flourish that deliberately cuts itself off from its roots, and the roots of our Western civilization are in the Greek and Latin classics, together with the Bible. People who ignore such areas of study disable themselves from appreciating their cultural heritage.

What factor do you think is more likely than any other to decide Christianity’s influence upon the secular thought of the next decade?

The faithfulness of Christian people to the essential gospel of redeeming grace, intelligently believed and clearly proclaimed. If Christianity is thought to say the same sort of thing, albeit in a religious idiom, as, say, the United Nations says in a nonreligious idiom, its influence on secular thought will be imperceptible.

What is your attitude toward mass evangelism?

There is no nobler gift than the gift of the evangelist—a gift I do not possess. You will not think I am decrying mass evangelism for a moment, however, if I add that one-to-one is the most effective. Only personal evangelism could have reached, for example, Nicodemus or the woman at the well.

What do you think is the proper line to take on the doctrine of the Second Advent?

What is not important is a preoccupation with matters of timetable. The Gospels remind us that we do not know the time; I think they imply also that we do not know the manner. I must confess to some uneasiness over the fact that colleges and schools have been founded on some finely drawn eschatological interpretation. What is important is that we be prepared for the coming of the Son of Man.

Carl F. H. Henry, first editor of Christianity Today, is lecturer at large for World Vision International. An author of many books, he lives in Arlington, Virginia.