A CHRISTIANITY TODAY editor gives his “on-the-scene” impression.

Leading the parade was a man without any legs. He was fully uniformed, in the blue suit and white cap of the United States Marine Corps. He proceeded in a wheelchair, and it was plain that in Vietnam he had lost his limbs but not his patriotism. He held an American flag proudly aloft.

Behind the Marine marched unlikely and motley troops. They were not uniformed, and their parade was straggly—two men wide here, four or five wide there. These men were carrying signs, picketing. And they sang. But not soldier songs, not protest songs. Their song was “Victory in Jesus,” chorused hesitantly and a little timidly. Clearly, the marchers had sung the old hymn many times before—but not on the street, not protesting in their beloved America. These marchers, these protestors, were fundamentalist pastors. At the end of their line came a man pulling a cross equipped with a wheel at its foot.

The pastors, coming from more than 30 states, marched in the county seat of Cass County, Nebraska. They were protesting the jailing of Everett Sileven (Sil-e-ven), pastor of Faith Baptist Church, 15 miles away in Louisville. Sileven was in jail because his church continued to operate a private school for 29 children, though it lacked a state license and certified teachers.

Protesting is new for twentieth-century fundamentalists. Blacks, feminists, and antiwar demonstrators all learned two decades ago the skills of protest—marches, sit-ins, boycotts. But most fundamentalists rallied for law and order when blacks took to the streets; they are still opposed to feminism; and they believe the Vietnam War was a mistake only in that it was not fought intensely enough to be won. These conservative Christians are learning about protest quickly, however.

They know the biggest club they can wield against the state of Nebraska is public opinion. And they know that public opinion is reached and finally swayed through the conduit of mass media. Marches drew those media and made “good” television. A parade led by a wheelchair-bound, flag-bearing Marine made even better television. The garnish of a man dragging a cross on a training wheel made some of the journalists think they had been transplanted into a Flannery O’Connor story.

But the fundamentalists, intuitively and consciously, knew the power of the symbolic. The Louisville church had been padlocked to stop classes inside. Soon after police removed lock and chain to open the church for Wednesday evening worship, the fundamentalists put their own lock back on. The Marine, yet in uniform, posed with chain cutters at the door. Shutters clicked, videotapes whirled, and the message went out in the form of an evocative image: a man who had fought for freedom—who had given up his legs for freedom—and who had come back home to find a Baptist church chained shut.

It attracts attention. It moves hearts. It applies torque to that amorphous, all-important American force, public opinion. “It’s all a poker game,” a series of orchestrated bluffs, admitted Greg Dixon, one of the leaders at Louisville. Dixon, an Indianapolis pastor and national secretary for the Moral Majority, at one point thanked a New York Times reporter and praised the news media in general. “We wouldn’t be anywhere without them.”

Louisville was not the first place fundamentalists understood the power of the press. The Separation of Church and Freedom, subtitled “A War Manual for Christian Soldiers,” was published in 1980. It includes an entire chapter on press relations. “Our freedom will live or die, not in the U.S. Supreme Court, but in the court of public opinion,” wrote Pastor Kent Kelly, who fought the church education battle in his state of North Carolina. “Get on your knees. Get out the Bible. Meet the attorneys. Meet the issues. But don’t forget to meet the press!”

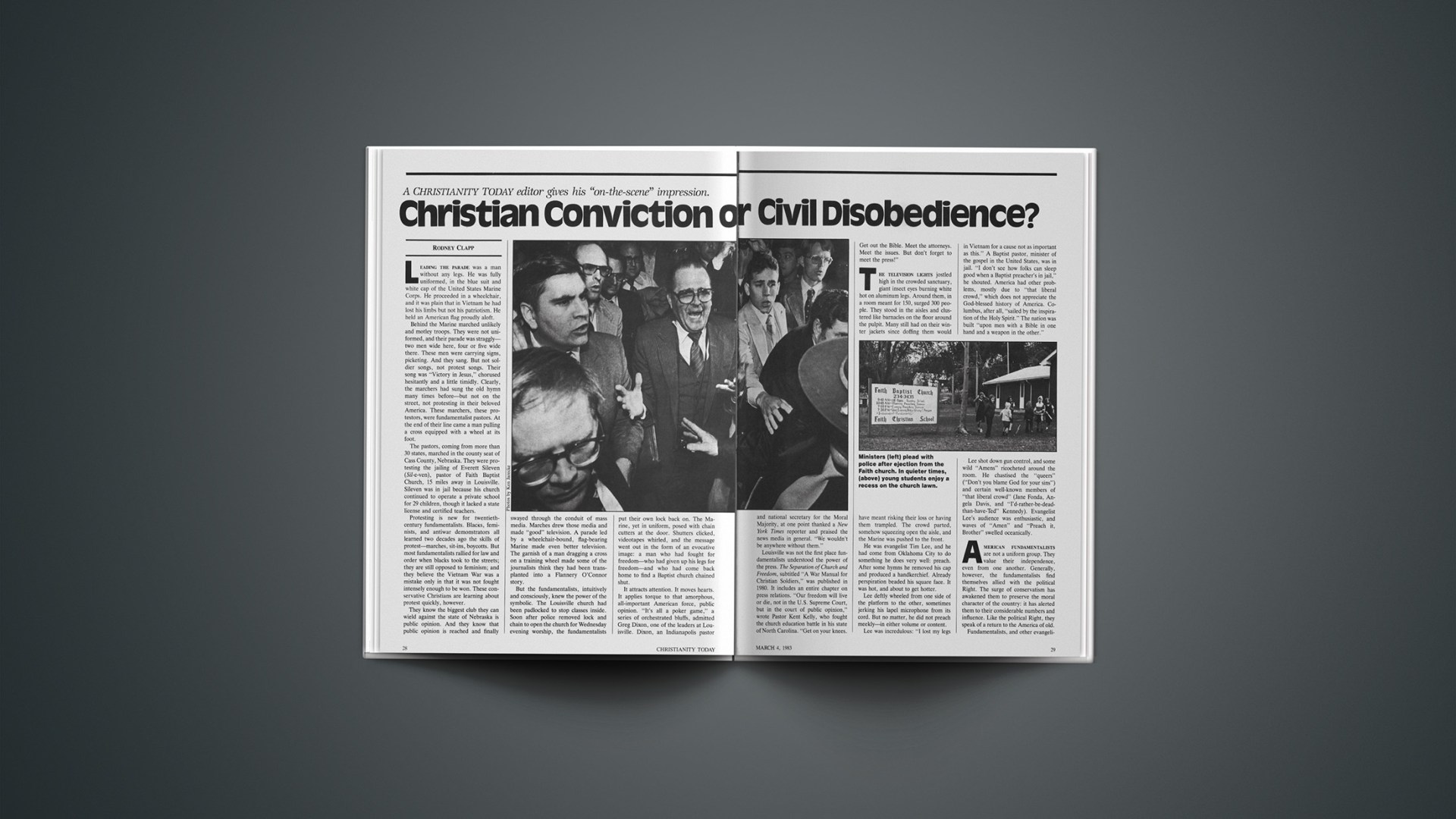

The television lights jostled high in the crowded sanctuary, giant insect eyes burning white hot on aluminum legs. Around them, in a room meant for 150, surged 300 people. They stood in the aisles and clustered like barnacles on the floor around the pulpit. Many still had on their winter jackets since doffing them would have meant risking their loss or having them trampled. The crowd parted, somehow squeezing open the aisle, and the Marine was pushed to the front.

He was evangelist Tim Lee, and he had come from Oklahoma City to do something he does very well: preach. After some hymns he removed his cap and produced a handkerchief. Already perspiration beaded his square face. It was hot, and about to get hotter.

Lee deftly wheeled from one side of the platform to the other, sometimes jerking his lapel microphone from its cord. But no matter, he did not preach meekly—in either volume or content.

Lee was incredulous: “I lost my legs in Vietnam for a cause not as important as this.” A Baptist pastor, minister of the gospel in the United States, was in jail. “I don’t see how folks can sleep good when a Baptist preacher’s in jail,” he shouted. America had other problems, mostly due to “that liberal crowd,” which does not appreciate the God-blessed history of America. Columbus, after all, “sailed by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.” The nation was built “upon men with a Bible in one hand and a weapon in the other.”

Lee shot down gun control, and some wild “Amens” ricocheted around the room. He chastised the “queers” (“Don’t you blame God for your sins”) and certain well-known members of “that liberal crowd” (Jane Fonda, Angela Davis, and “I’d-rather-be-dead-than-have-Ted” Kennedy). Evangelist Lee’s audience was enthusiastic, and waves of “Amen” and “Preach it, Brother” swelled oceanically.

American fundamentalists are not a uniform group. They value their independence, even from one another. Generally, however, the fundamentalists find themselves allied with the political Right. The surge of conservatism has awakened them to preserve the moral character of the country: it has alerted them to their considerable numbers and influence. Like the political Right, they speak of a return to the America of old.

Fundamentalists, and other evangelicals like Francis Schaeffer, have proposed various strategies of restoration. The September 21, 1981, issue of Moral Majority Report suggested it might be appropriate to withhold taxes if Congress “does not have the backbone to pass a Human Life Amendment.” Schaeffer’s A Christian Manifesto (Crossway, 1981) has, in fact, been endorsed by organizations favoring the abolition of income taxes, although Schaeffer does not advocate that in the book. The New York Patriots Society said Manifesto is “going to shake up today’s church” and advised, “Buy it for your friends who hide behind Romans 13.” The religious/political Right’s co-opting of Schaeffer is evidenced in the purchase by Jerry Falwell’s “Old Time Gospel Hour” of 62,000 copies of Manifesto for distribution. Ken Campbell (sometimes called the Canadian Falwell) bought 8,000.

Pastor Kent Kelly, in his book The Separation of Church and Freedom, believes the nation now has a humanist government but “Christians were here first.” He continued, “If the humanists want a nation based on their religion, which is where we stand today through their efforts, they need to go somewhere else and start one.…” In this view, Christians once controlled America, and can do it again.

A low-profile proposal by an influential evangelical predicted Christians will excel in law, politics, and the media, “and will take over more and more of the centers of power in these areas. This is so because we know how to run the world better than those who have wrong views of basic reality.…”

What is the unbiased Christian to make of all this ferment? In Nebraska, there are mild demonstrations and a pastor is jailed. Thinkers as influential as Francis Schaeffer call for activism, even civil disobedience. The thoughtful Christian is increasingly pressured to take a stand. But where, and how, should she or he stand?

In making up our minds, we might consider Tolstoy’s statement: “In truth, the words ‘a Christian State’ resemble the words ‘hot ice’.” One hundred fifty years ago slave trade was flourishing; some would question whether America was more truly Christian then than now. Or was it more Christian at the turn of the century, when social Darwinism and industrialization had spawned child labor? Historians debate how “Christian” America’s history is. Yet, no matter how deeply Christian America may once have been, there was never a golden age, just as there has never been “hot ice.”

One is given further pause when he considers that America’s present-day pluralism must affect any approach treating the nation as a country ruled directly by God in much the same way as Judah in the seventh century B.C. Talk of a quasi-theocracy (whatever it might be called) ought to be offset by a sober consideration of America’s pluralism. Our nation was once a great melting pot, but is now split linguistically, culturally, and religiously. This may make it difficult or impossible to reestablish the degree of Christian influence America knew a century ago, especially when Christians (as illustrated by Lee’s sermon) can register only rage at the diverse groups currently well established in our culture. Surely a degree of tolerance is a component of the compassion Christ calls us to embrace. The conservative Christian activist commendably wants to influence society for Christ, but the process must always be exactly that: one of influence, not compulsion.

“Mob rule has triumphed Louisville.” So began the lead editorial of the Omaha World-Herald the day Everett Sileven was set free. After a week of rallies, pickets, all-night vigils, and perpetual phone calls to law keepers and legislators, Faith Baptist pastor Sileven was released from jail. It was a time to celebrate. In Louisville, cars were parked a half-mile in all directions from the church. The television lights were back on, and 300 people were back in the 150-person sanctuary. This time no one was noticing the heat.

“Victory in Jesus” was being sung again, confidently, in an accustomed setting, and resonating cobwebs out of corners. Tears streamed, and handkerchiefs waved: white flags surrendering to joy. Sileven, trailed by his tall and stately wife, bumped, and was pulled, from one hug and slap on the back to the next. They celebrated, even as the ink dried on the final morning edition of that day’s World-Herald.

The World-Herald was not celebrating. “Hundreds of Moral Majority members and other fundamentalist Christians” had gathered in support of Faith Baptist. “By sheer numbers and the implicit threat of violence, supporters of the school … have intimidated authorities and persuaded a judge to suspend a properly imposed court order.” That, in the judgment of the newspaper, was “chilling.”

“Particularly ironic is the prominence of the American flag in demonstrations contradicting what the flag stands for: a nation ruled by law,” the editorial continued. “When intimidation and the possibility of violence become political weapons, there is no safety for anyone under any law.”

Yet civil disobedience, however mild it may have been at Louisville, was no easy thing for the fundamentalists there. Few Americans remain as genuinely and unabashedly patriotic as fundamentalists. They love their country’s heritage, including its legal foundations. But fundamentalists are also committed people. In Nebraska, they were torn between two commitments: their government, and Jesus Christ.

All Christians at least potentially face the dilemma of the Louisville fundamentalists. What conservative Christians considered unthinkable 20 years ago has now come to pass: they find themselves at odds with the United States government. The question of whether or not to be civilly disobedient may confront more and more Christians in coming years. Once again, then, we must ask: Where should we stand?

Civil disobedience is not new in Christianity. Ecclesiastical and governmental authorities threatened Christ to force him to stop his ministry. He disobeyed. Peter, Paul, and other New Testament Christians—despite their exhortations of general obedience—occasionally found themselves at odds with the authorities. By the fifth century, Augustine could declare, “A law that is not just goes for no law at all.” Tyndale resisted, and was executed. Bunyan refused to get a license to preach, and was jailed. Fifteen years before Thoreau (not a Christian) spent a night in jail for refusing to pay his poll tax, two Georgia missionaries defied a licensing law. Cherokee Indians were required to give up their land claims, and missionaries, to obtain preaching licenses, were by law supposed to advise the Indians to relinquish their claims. One of the missionaries wrote that he refused to give such advice because he was under a “clear moral obligation—a question of right or wrong—of keeping … the commands of God.”

It is the question of lordship that presents dilemmas for the patriotic Christian. Scripture evidences a clear concern for lawful order—the Antichrist, after all, is preeminently seen as “the man of lawlessness” (2 Thess. 2:3). And Romans 13:1–7 counsels Christian obedience to the government, as do Titus 3:1–2 and 1 Peter 2:13. But in Christ and the Powers (Herald Press, 1962), Hendrik Berkhof notes nine other New Testament passages that demonstrate ambivalence toward “principalities and powers” such as the state. He notes that government is a necessary mediator of order and justice in society, and therefore good. But government is also part of the fallen order, and so it may itself attempt to become a god. When the state’s will contradicted that of God, the apostles chose to resist it. Their teaching and example are of general obedience to the state, but never-failing obedience to the lordship of Christ.

What triumphed at Louisville was not the World Herald’s “mob rule.” It is true, as constitutional authority Alexander Bickel recognized, that all civil disobedience is coercive in its “ultimate intent,” After all, civil disobedience is a last resort, an attempt at correction after more ordinary forms of persuasion have failed.

It is also true that the anarchic potential of civil disobedience cannot be denied. Social philosopher Hannah Arendt spoke of the “anarchic nature of divinely inspired consciences, so blatantly manifest in the beginnings of Christianity.” An appeal directly to God sails over the heads of magistrates. It instantaneously produces crisis and confrontation, for who (or what) can be appealed to above God? Indeed, Paul apparently tried to restrict that potential for civil or moral anarchy, even advising slaves to accept their status unless freedom was offered (1 Cor. 7:20–22).

Scripture would advise us, then, not to take civil disobedience lightly. It must be undertaken only with caution, prayer, and the counsel of the church. It is an act of gravity since it is, in a sense, law breaking. But it is law breaking of a unique kind, an activity that affirms law in general while violating law in the particular case.

Aristotle said the good man could be a good citizen only in a good state. Thus the Christian—striving always to be a good man in the Christlike sense—should not be surprised if at some time he has to be a “bad” citizen in a fallen society. Gen. William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, said, “No great cause ever achieved a triumph before it furnished a certain quota to the prison population.” Most men go to jail because they are worse than their neighbors; a few go because they are better.

And jail is often where the civilly disobedient person lands. That is how he or she affirms the legal structure while violating a particular law. Law preserves the order and health of a society: the person who is civilly disobedient has classically accepted that, and when he reluctantly defies a law, he accepts the penalty. He may be an outlaw, but no true civil disobedient is a fugitive.

The Louisville fundamentalists, still uncomfortable with confronting government, may be reassured to know that civil disobedience is very much of the American heritage. Arendt argues that it is uniquely American in substance, and that the American system is the government most capable of coping with it, “not, perhaps, in accordance with the statutes, but in accordance with the spirit of its laws.” Evangelical ethicist Stephen Charles Mott notes that “civil disobedience, stepping into the breaches of constitutional order, gives justice a second chance.” Without such a safety valve, violence and even revolution would be more likely. “Thus,” Mott observes, “civil disobedience can truly be a way of paying our obligations of respect and honor to the the political system (Rom. 13:7).

A visitor to faith baptist church crossed the starchy autumn grass of the church lawn. Ahead of him was a mongrel, chewing its paws. A young, jeans-clad Louisville resident passed on the sidewalk. He thought the visitor was a fundamentalist pastor, and commanded the animal: “Bite him, dog, bite him.”

Protest did not make the fundamentalists popular in Nebraska. Unfortunately, civil disobedience appears guaranteed to alienate and enrage. It has done so from the time of Socrates to that of Martin Luther King, Jr. The Louisville incident serves to remind all Christians (whether or not they approved of fundamentalist conduct there) of their inherent position of tension in this world. They are in the world but not of it. Christians seek to redeem the earth and all that is in it, but admit they are “aliens and strangers on earth” (Heb. 11:13).

The ancient Epistle to Diognetus notes that Christians must pass their lives on earth but are citizens of heaven, that they love all men but are persecuted by all. These words from the early church seem terribly odd to contemporary American Christians. A possible lesson of Louisville may be that the lordship of Christ can be uncanny and unnerving—even to Christians.