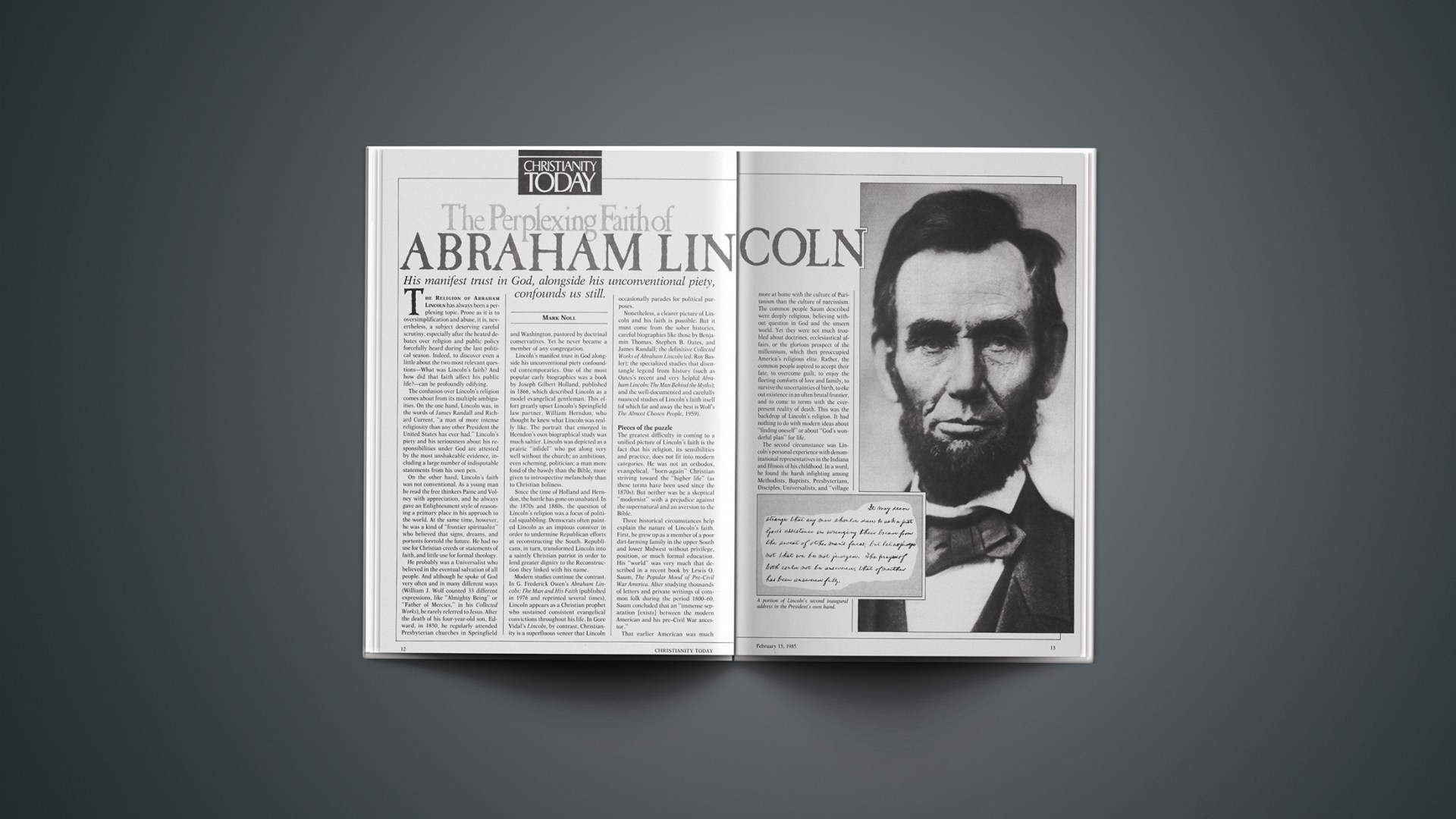

His manifest trust in God, alongside his unconventional piety, confounds us still.

The Religion of Abraham Lincoln has always been a perplexing topic. Prone as it is to oversimplification and abuse, it is, nevertheless, a subject deserving careful scrutiny, especially after the heated debates over religion and public policy forcefully heard during the last political season. Indeed, to discover even a little about the two most relevant questions—What was Lincoln’s faith? And how did that faith affect his public life?—can be profoundly edifying.

The confusion over Lincoln’s religion comes about from its multiple ambiguities. On the one hand, Lincoln was, in the words of James Randall and Richard Current, “a man of more intense religiosity than any other President the United States has ever had.” Lincoln’s piety and his seriousness about his responsibilities under God are attested by the most unshakeable evidence, including a large number of indisputable statements from his own pen.

On the other hand, Lincoln’s faith was not conventional. As a young man he read the free thinkers Paine and Volney with appreciation, and he always gave an Enlightenment style of reasoning a primary place in his approach to the world. At the same time, however, he was a kind of “frontier spiritualist” who believed that signs, dreams, and portents foretold the future. He had no use for Christian creeds or statements of faith, and little use for formal theology.

He probably was a Universalist who believed in the eventual salvation of all people. And although he spoke of God very often and in many different ways (William J. Wolf counted 33 different expressions, like “Almighty Being” or “Father of Mercies,” in his Collected Works), he rarely referred to Jesus. After the death of his four-year-old son, Edward, in 1850, he regularly attended Presbyterian churches in Springfield and Washington, pastored by doctrinal conservatives. Yet he never became a member of any congregation.

Lincoln’s manifest trust in God alongside his unconventional piety confounded contemporaries. One of the most popular early biographies was a book by Joseph Gilbert Holland, published in 1866, which described Lincoln as a model evangelical gentleman. This effort greatly upset Lincoln’s Springfield law partner, William Herndon, who thought he knew what Lincoln was really like. The portrait that emerged in Herndon’s own biographical study was much saltier. Lincoln was depicted as a prairie “infidel” who got along very well without the church; an ambitious, even scheming, politician; a man more fond of the bawdy than the Bible, more given to introspective melancholy than to Christian holiness.

Since the time of Holland and Herndon, the battle has gone on unabated. In the 1870s and 1880s, the question of Lincoln’s religion was a focus of political squabbling. Democrats often painted Lincoln as an impious conniver in order to undermine Republican efforts at reconstructing the South. Republicans, in turn, transformed Lincoln into a saintly Christian patriot in order to lend greater dignity to the Reconstruction they linked with his name.

Modern studies continue the contrast. In G. Frederick Owen’s Abraham Lincoln: The Man and His Faith (published in 1976 and reprinted several times), Lincoln appears as a Christian prophet who sustained consistent evangelical convictions throughout his life. In Gore Vidal’s Lincoln, by contrast, Christianity is a superfluous veneer that Lincoln occasionally parades for political purposes.

Nonetheless, a clearer picture of Lincoln and his faith is possible. But it must come from the sober histories, careful biographies like those by Benjamin Thomas, Stephen B. Oates, and James Randall; the definitive Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (ed. Roy Basler); the specialized studies that disentangle legend from history (such as Oates’s recent and very helpful Abraham Lincoln: The Man Behind the Myths); and the well-documented and carefully nuanced studies of Lincoln’s faith itself (of which far and away the best is Wolf’s The Almost Chosen People, 1959).

Pieces Of The Puzzle

The greatest difficulty in coming to a unified picture of Lincoln’s faith is the fact that his religion, its sensibilities and practice, does not fit into modern categories. He was not an orthodox, evangelical, “born-again” Christian striving toward the “higher life” (as these terms have been used since the 1870s). But neither was he a skeptical “modernist” with a prejudice against the supernatural and an aversion to the Bible.

Three historical circumstances help explain the nature of Lincoln’s faith. First, he grew up as a member of a poor dirt-farming family in the upper South and lower Midwest without privilege, position, or much formal education. His “world” was very much that described in a recent book by Lewis O. Saum, The Popular Mood of Pre-Civil War America. After studying thousands of letters and private writings of common folk during the period 1800–60, Saum concluded that an “immense separation [exists] between the modern American and his pre-Civil War ancestor.”

That earlier American was much more at home with the culture of Puritanism than the culture of narcissism. The common people Saum described were deeply religious, believing without question in God and the unseen world. Yet they were not much troubled about doctrines, ecclesiastical affairs, or the glorious prospect of the millennium, which then preoccupied America’s religious elite. Rather, the common people aspired to accept their fate, to overcome guilt, to enjoy the fleeting comforts of love and family, to survive the uncertainties of birth, to eke out existence in an often brutal frontier, and to come to terms with the ever-present reality of death. This was the backdrop of Lincoln’s religion. It had nothing to do with modern ideas about “finding oneself” or about “God’s wonderful plan” for life.

The second circumstance was Lincoln’s personal experience with denominational representatives in the Indiana and Illinois of his childhood. In a word, he found the harsh infighting among Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Disciples, Universalists, and “village atheists” repulsive. As a consequence, Lincoln several times professed willingness to join a church that required nothing of its members but heartfelt love to God and to one’s neighbors. The competing creeds of the churches were not for him.

The third circumstance was instruction in reality by the coldest master, death. The passing of his mother when he was nine, the death of his sister shortly after her marriage, the death of two of his sons (in 1850 and at the White House in 1862), the death of several close friends in the early days of the Civil War (his Civil War), and increasingly, the heart-wrenching lists of casualties from the battlefields, left him no taste for easy believism, no escape from the mysteries of God and the universe.

The truly remarkable thing about Lincoln’s religion was how these circumstances drove him to deeper contemplations of God and the divine will. The external Lincoln, casual about religious observance, hid a man of profound morality and an almost unbearable God consciousness binding a vision for the nation with the providence of God. This religion, the real faith of Abraham Lincoln, was made up of a nonsectarian attachment to the Scriptures, a growing commitment to prayer, an unswerving moral consciousness, and a belief that American ideals closely reflected the principles of divine morality.

Although details are scanty about his early study, Lincoln somewhere and somehow acquired a wide and deep knowledge of the Scriptures. In his great debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858, he several times corrected his opponent’s inaccurate use of the Bible. After early doubts about the veracity of the Scriptures, he became convinced that they contained the voice of God. In a well-attested story from the last year of his life, Lincoln told an old friend who called himself a skeptic, “Take all this book upon reason that you can, and the balance on faith, and you will live and die a happier and better man” (Wolf, p. 86).

In that same year he accepted a magnificent ceremonial Bible from “the Loyal Colored People of Baltimore” and replied with oft-quoted words, “In regard to this Great Book, I have but to say, it is the best gift God has given to man. All the good the Saviour gave to the world was communicated through this book. But for it we could not know right from wrong. All things most desirable for man’s welfare, here and hereafter, are to be found portrayed in it” (Wolf, CM 7:542). Much earlier, in 1846, when a congressional candidate accused Lincoln of infidelity, he had replied that though he was a member of no church, he had “never denied the truth of the Scriptures” (Wolf, CW 1:382). The circumstances of life only deepened this early respect.

Unconfessional Christianity

Lincoln, like his political heroes Washington and Jefferson, was intensely private about his religious practice. But it does seem clear that he came to pray more regularly and devoutly as he moved through life. In the middle of the war, he wrote to two Iowans who had commended him for the recent Emancipation Proclamation and assured him of their prayers. In response, Lincoln said he was “sustained by the good wishes and prayers of God’s people” in such difficulties (Wolf, CW 6:39). And he often spoke of his own appeals to God for a speedy, just end to the conflict.

As was his habit, Lincoln joked about matters that were most important to him. On more than one occasion he told the story of two Quaker women discussing the war. “I think,” said the first, “Jefferson Davis will succeed.”

The second asked, “Why does thee think so?”

The reply came, “Because Jefferson is a praying man.”

“And so is Abraham a praying man,” was the immediate rejoinder.

“Yes,” said the first, “but the Lord will think Abraham is joking” (Oates, pp. 151–2).

Lincoln’s personal integrity was undeviating throughout his adult life. Legendary accounts of how as a youth he would expend vast energy to redress trivial discrepancies over pennies or borrowed books are not required to perceive a person of steady and unswerving morality. And nowhere does his public integrity appear more clearly than in his opposition to slavery.

Far too many learned books have discussed this issue to give more than the briefest summary here. But it seems clear that Lincoln was motivated in his struggle first by his feeling that slavery violated American principles of freedom. Second, he came to be more and more convinced of the rights of all people—even blacks—under God and under the law.

Lincoln was never a modern egalitarian, and he clung for a long time to the idea that liberated slaves could be resettled in Africa. Moreover, the timing of emancipation was politically expedient to be sure. Yet he also held with growing conviction that God had called him to national leadership precisely to extend freedom to all who lived in America, whether they had been traditionally granted the rights of citizenship or not. Contemporary advocates of abolition, like the ex-slave statesman Frederick Douglass, recognized the integrity of Lincoln’s actions. After emancipation was proclaimed on January 1, 1863, for slaves in occupied territory, Douglass, who had earlier criticized the president’s delays, wrote in his journal, “We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous decree” (Oates, p. 107). Lincoln did not posture when he invoked “the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God” in the last words of the Proclamation.

Much of Lincoln’s refined moral sensibility grew out of his love for American ideals. As a youth he had read Parson Mason Weems’s laudatory biography of George Washington and many other inspiring accounts of the nation’s founding. To Lincoln the ideals of the country, rather than the political compromises that had been necessary to launch the government, became beacon lights for his own efforts. He could call his country “the almost chosen people” and speak of the United States as “the last, best hope of earth.” But this represented, in Martin Marty’s phrase, a “prophetic” style of civil religion. It did not equate the nation or its actions with God’s blessing, but rather felt that the founding ideals had given the country a uniquely moral vision. This was a vision, moreover, that condemned national immoralities much more readily than sanctioned national complacency.

This, then, is the personal story that lies behind Lincoln’s public life. The manifest morality of that career arose from what Wolf calls a “biblical religion,” rather than from any confessional variety of Christianity. It came to expression in his debates with Douglas in 1858 over the extension of slavery, in several of the speeches he gave in the late 1850s, in his first inaugural address of 1861, in his proclamation of a national fast in 1863, and above all, in the eloquent simplicity of the second inaugural of 1865.

It is no exaggeration to say that there is nothing like this address in the long, often tedious, and frequently hypocritical history of American political discourse. Lincoln briefly reviewed the circumstances that led to the conflict: “Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.” He then singled out division over the extension of slavery as the spar that began a conflict that had lasted far longer than either side expected.

Everything common in American politics, at least in living memory, would lead us to expect that at this point in the speech Lincoln would begin to denounce the South (his foreign enemy) and his opponents in the North, and to justify his own actions and the actions of his party. But what came instead was utterly different. The last half of this short address, complete with quotations from Matthew 18:7 and Psalm 19:9, deserves to be quoted in full:

“Neither [side] anticipated that the cause of the conflict [i.e., slavery] might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. ‘Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!’ If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.’

“With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations” (Wolf, CW, 8:333).

Five weeks after he delivered this address on March 4, 1965, Lincoln was dead—and American politics returned to “normal.” What was missing immediately thereafter, and what has been largely missing since, is Lincoln’s unique blend of convictions:

• that the nation embodies lofty ideals about human dignity and worth;

• that these ideals are an expression of truths grounded in the Scriptures of the New, but especially of the Old Testament;

• that these ideals show us how far short we fall in most of our national life;

• that God’s judgment falls rightfully upon all of us, for personal and national sins alike;

• that national trauma is regularly deserved for the way in which we, as citizens, sanction or tolerate abuses against humanity;

• and that in spite of our weakness and guilt, God’s providence rules over the affairs of men and nations.

No one before or after Lincoln said such things so clearly. We have had many to champion the ideals of the nation, but usually without Lincoln’s clear sense that no party, no self-appointed guardians of public morality, no narrowly factional interest group, can embody the national ideals. We have had many call the nation to repentance, but few with the conviction that all stand guilty before God—even those who issue the call. We have had many who equate the United States with transcendent good, and more recently many who have identified it with root evil. But we have had precious few who, with Lincoln, have perceived how thoroughly the good and evil intermingle in our heritage; how completely our hope for the public future runs up against the legacies of private and corporate wrong.

In the end it is an irony that Lincoln, the man of deep, but unconventional faith, has so much to teach those of us whose evangelical faith is more orthodox and whose doctrinal bedrock is the lordship of Jesus Christ. A harsh upbringing, a melancholy disposition, a profound understanding of those Scriptures that portray the overarching providence of God, and an existential awareness of life’s transitory character gave Lincoln a grasp on reality that few of us ever achieve.

Abraham Lincoln knew he was no saint. “I have often wished that I was a more devout man than I am,” he told a delegation of Baltimore Presbyterians in 1863. Yet this ability to see himself realistically—to acknowledge that he had no right to condemn the unjust as if he had never sinned—allowed him to glimpse the realistic potential of human dignity. Even more, it allowed him to recognize that above and beyond all nations and national ideals, God prevailed. “Amid the greatest difficulties of my Administration,” he went on to the Baltimore Presbyterians, “when I could not see any other resort, I would place my whole reliance in God, knowing that all would go well, and that He would decide for the right.”

Lincoln had no illusions about what it meant for “all” to “go well.” The reason was that, whatever the deficiencies in his personal faith or religious practice, he knew, at its most profound level, where the world, the nation, and his own destiny fit into the scheme of things. Once more his humor illustrates this most clearly. On several occasions during the war he told visitors who prayed for God to be on “their” side that he was much more concerned that they be on God’s side. This is a message that, though its author is long dead, deserves to resound in our own day.