Five new titles for your consideration this spring.

Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, edited by Walter A. Elwell (Baker Book House, 1984, 1204 pp.; $29.95)

Thomas Corneille published the ancestor of modern theological and philosophical encyclopedias in 1696, but it was Peter Bayle’s Dictionnaire historique et critique (which came out the following year) that established the genre. Bayle used his alphabetized collection of articles to attack anything he thought was superstitious, irrational, or stupid—especially Christianity. In fact, he meant to destroy the Christian faith, but would do so by intellectual undermining, not bludgeoning.

The theological dictionary, then, came into being as an antidote to the faith—making it all the more ironic that the latest member of the species, the Evangelical Dictionary of Theology (EDT) avows intent to educate Christians from an evangelical point of view.

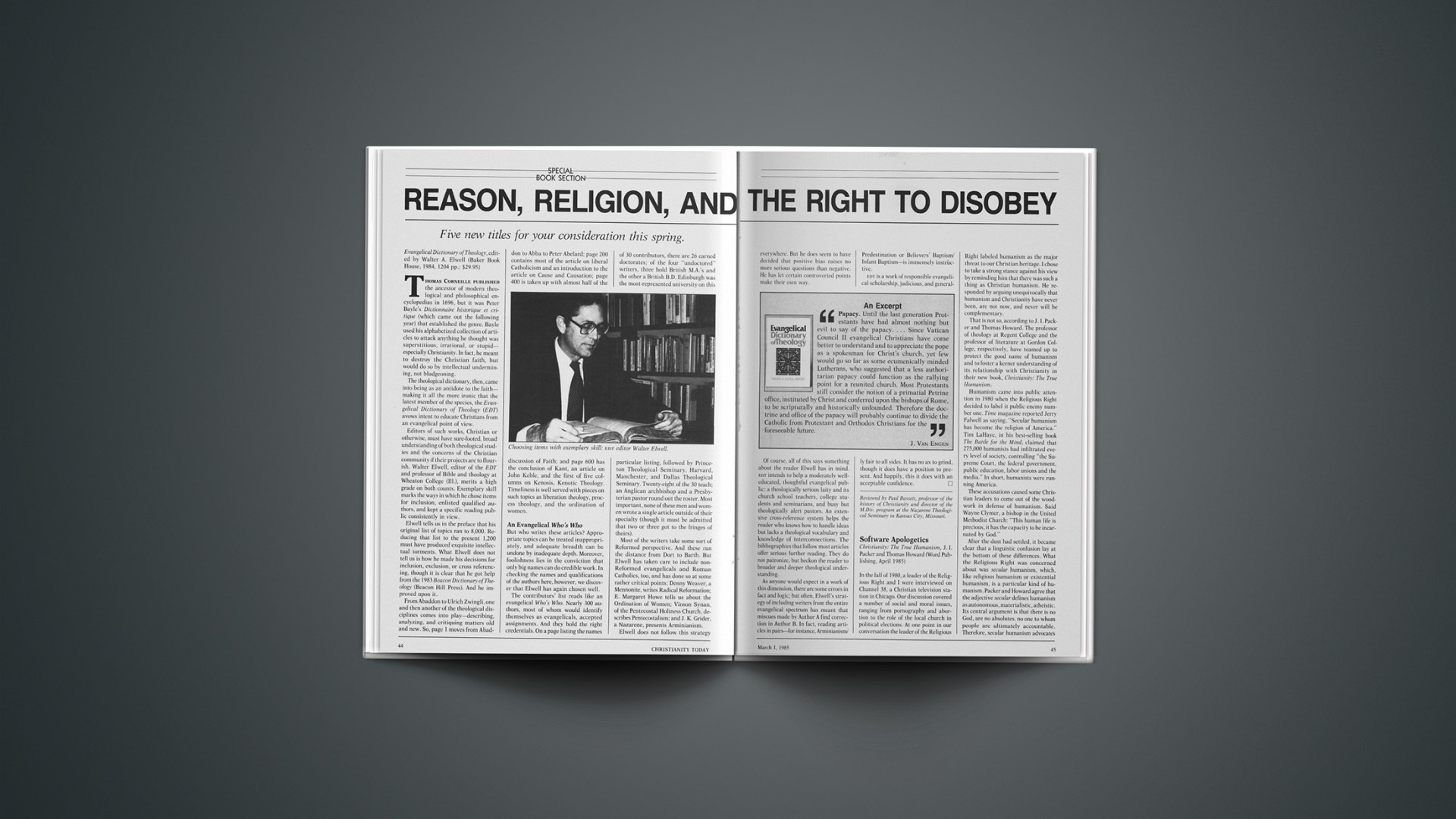

Editors of such works, Christian or otherwise, must have sure-footed, broad understanding of both theological studies and the concerns of the Christian community if their projects are to flourish. Walter Elwell, editor of the EDT and professor of Bible and theology at Wheaton College (Ill.), merits a high grade on both counts. Exemplary skill marks the ways in which he chose items for inclusion, enlisted qualified authors, and kept a specific reading public consistently in view.

Elwell tells us in the preface that his original list of topics ran to 8,000. Reducing that list to the present 1,200 must have produced exquisite intellectual torments. What Elwell does not tell us is how he made his decisions for inclusion, exclusion, or cross referencing, though it is clear that he got help from the 1983 Beacon Dictionary of Theology (Beacon Hill Press). And he improved upon it.

From Abaddon to Ulrich Zwingli, one and then another of the theological disciplines comes into play—describing, analyzing, and critiquing matters old and new. So, page 1 moves from Abaddon to Abba to Peter Abelard; page 200 contains most of the article on liberal Catholicism and an introduction to the article on Cause and Causation; page 400 is taken up with almost half of the discussion of Faith; and page 600 has the conclusion of Kant, an article on John Keble, and the first of five columns on Kenosis, Kenotic Theology. Timeliness is well served with pieces on such topics as liberation theology, process theology, and the ordination of women.

An Evangelical Who’s Who

But who writes these articles? Appropriate topics can be treated inappropriately, and adequate breadth can be undone by inadequate depth. Moreover, foolishness lies in the conviction that only big names can do credible work. In checking the names and qualifications of the authors here, however, we discover that Elwell has again chosen well.

The contributors’ list reads like an evangelical Who’s Who. Nearly 300 authors, most of whom would identify themselves as evangelicals, accepted assignments. And they hold the right credentials. On a page listing the name of 30 contributors, there are 26 earned doctorates; of the four “undoctored” writers, three hold British M.A.’s and the other a British B.D. Edinburgh was the most-represented university on this particular listing, followed by Princeton Theological Seminary, Harvard, Manchester, and Dallas Theological Seminary. Twenty-eight of the 30 teach; an Anglican archbishop and a Presbyterian pastor round out the roster. Most important, none of these men and women wrote a single article outside of their specialty (though it must be admitted that two or three got to the fringes of theirs).

Most of the writers take some sort of Reformed perspective. And these run the distance from Dort to Barth. But Elwell has taken care to include non-Reformed evangelicals and Roman Catholics, too, and has done so at some rather critical points: Denny Weaver, a Mennonite, writes Radical Reformation; E. Margaret Howe tells us about the Ordination of Women; Vinson Synan, of the Pentecostal Holiness Church, describes Pentecostalism; and J. K. Grider, a Nazarene, presents Arminianism.

Elwell does not follow this strategy everywhere. But he does seem to have decided that positive bias raises no more serious questions than negative. He has let certain controverted points make their own way.

Of course, all of this says something about the reader Elwell has in mind. EDT intends to help a moderately well-educated, thoughtful evangelical public: a theologically serious laity and its church school teachers, college students and seminarians, and busy but theologically alert pastors. An extensive cross-reference system helps the reader who knows how to handle ideas but lacks a theological vocabulary and knowledge of interconnections. The bibliographies that follow most articles offer serious further reading. They do not patronize, but beckon the reader to broader and deeper theological understanding.

As anyone would expect in a work of this dimension, there are some errors in fact and logic; but often, Elwell’s strategy of including writers from the entire evangelical spectrum has meant that miscues made by Author A find correction in Author B. In fact, reading articles in pairs—for instance, Arminianism/Predestination or Believers’ Baptism/Infant Baptism—is immensely instructive.

EDT is a work of responsible evangelical scholarship, judicious, and generally fair to all sides. It has no ax to grind, though it does have a position to present. And happily, this it does with an acceptable confidence.

Reviewed by Paul Bassett, professor of the history of Christianity and director of the M.Div. program at the Nazarene Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri.

An Excerpt

“Papacy. Until the last generation Protestants have had almost nothing but evil to say of the papacy.… Since Vatican Council II evangelical Christians have come better to understand and to appreciate the pope as a spokesman for Christ’s church, yet few would go so far as some ecumenically minded Lutherans, who suggested that a less authoritarian papacy could function as the rallying point for a reunited church. Most Protestants still consider the notion of a primatial Petrine office, instituted by Christ and conferred upon the bishops of Rome, to be scripturally and historically unfounded. Therefore the doctrine and office of the papacy will probably continue to divide the Catholic from Protestant and Orthodox Christians for the foreseeable future.”

Software Apologetics

Christianity: The True Humanism, J. I. Packer and Thomas Howard (Word Publishing, April 1985)

In the fall of 1980, a leader of the Religious Right and I were interviewed on Channel 38, a Christian television station in Chicago. Our discussion covered a number of social and moral issues, ranging from pornography and abortion to the role of the local church in political elections. At one point in our conversation the leader of the Religious Right labeled humanism as the major threat to our Christian heritage. I chose to take a strong stance against his view by reminding him that there was such a thing as Christian humanism. He responded by arguing unequivocally that humanism and Christianity have never been, are not now, and never will be complementary.

That is not so, according to J. I. Packer and Thomas Howard. The professor of theology at Regent College and the professor of literature at Gordon College, respectively, have teamed up to protect the good name of humanism and to foster a keener understanding of its relationship with Christianity in their new book, Christianity: The True Humanism.

Humanism came into public attention in 1980 when the Religious Right decided to label it public enemy number one. Time magazine reported Jerry Falwell as saying, “Secular humanism has become the religion of America.” Tim LaHaye, in his best-selling book The Battle for the Mind, claimed that 275,000 humanists had infiltrated every level of society, controlling “the Supreme Court, the federal government, public education, labor unions and the media.” In short, humanists were running America.

These accusations caused some Christian leaders to come out of the woodwork in defense of humanism. Said Wayne Clymer, a bishop in the United Methodist Church: “This human life is precious, it has the capacity to be incarnated by God.”

After the dust had settled, it became clear that a linguistic confusion lay at the bottom of these differences. What the Religious Right was concerned about was secular humanism, which, like religious humanism or existential humanism, is a particular kind of humanism. Packer and Howard agree that the adjective secular defines humanism as autonomous, materialistic, atheistic. Its central argument is that there is no God, are no absolutes, no one to whom people are ultimately accountable. Therefore, secular humanism advocates human self-determination, and freedom of the individual to do what brings the greatest pleasure and personal fulfillment.

However, unlike the Religious Right, Packer and Howard will not throw the term humanism into the closet of four-letter words. Humanism, they say, ultimately addresses the question, “What constitutes the good life—that is, the truly human life—for mankind?” Therefore, it is perfectly appropriate to speak of Christian humanism, for Christian humanism promotes the true human life.

Tender Mercies

Christianity: The True Humanism is software apologetics. It is not written to please those who want to “whip those secular humanists into a corner.” This is a book about tender mercies. Its appeal is to those who want to love the errant into the kingdom. Its vision of Jesus is not of the tough guy with a whip casting sinners out of the temple, but of the meek and mild Jesus with a towel, wiping dirty feet, acting out the role of the servant. In short, it is a reasoned, well-mannered, C. S. Lewis-type apologetic for the Christian faith. To be sure, the enemy is secular humanism, but the guns and bombs have been traded for gentle but incisive persuasion.

According to Packer and Howard, the real contrast between secular and Christian humanism is the quality of life they engender. Consider, we are asked, the differences in secular and Christian humanism when it comes to the life longing for freedom, the inner hope that keeps us going, the interrelationship between health and virtue, the source and practice of human dignity (and the kind of culture each produces), the sense of the sacred, and the feeling of personal esteem and identity. Where, our authors ask, does secular humanism leave us, and where does Christianity lead us in these matters?

At first, I wondered about this methodology. Is the book really setting forth Christianity as an alternative humanism? However, the more I read—the more I allowed the Christian persuasion of freedom, hope, human dignity, and other matters to lodge inside my soul, shape my perspective, help me envision the ideal—the more I felt the power of its argument. The book persuaded me that secular humanism cannot be defeated by arguing against the loss of historical religious sensibility; it is not put away by calling for a return to the principles that made America great; it will not be defeated by the power of a religious vote. Rather, the antidote to secularism is the power of life that is lived in humble submission to the God-man. He came to redeem us from the power of the Evil One and to call us to walk in his footsteps.

Indeed, true humanity was achieved in Jesus. And those who have been his followers, millions of them—apostles, martyrs, and saints—have left a testimony emblazoned in history that God in Christ can and does lead us into personal human fulfillment. Even more, he leads us to affirm the worth of humanity and to advocate the sanction of human life for all peoples, including the defenseless unborn child, the poor in the ghetto, the Jew harassed by the continuing presence of nazism, the old and infirm.

Christianity: The True Humanism is similar in methodology, then, to the second-century First Apology written by Justin Martyr. His appeal to the emperor Titus to become a Christian was based on the very thing the emperor sought. Titus, a man of enormous intellect, placed reason above all things. Justin called upon him to receive Jesus the Logos (reason) incarnate, the one in whom his life would find complete fulfillment. Packer and Howard, like Justin, are appealing to the humanist on the basis of what the humanist respects and desires most of all: a true experience of the human for himself and others. Come to Jesus Christ, the authors urge, for in him and him alone is found the true and ultimate source of humanity.

This approach is compelling. It recognizes the humanity of the opponent. It clearly sets forth two alternative paths—the one ultimately leading to the denial of what it means to be human, and the other leading to the affirmation of the humanity of all people, marred surely by sin, but awaiting release through repentance, conversion, and regeneration. In method and content, Christianity: The True Humanism is a tract for the times and stands in the tradition of the best apologetics that evidence both head and heart, mind and feeling, intellect and will.

Perhaps the book will ultimately help us all—fundamentalists, evangelicals, ecumenicals, Catholics and Orthodox—to find a rallying point, a unified center from which we can approach the secularists of our day and lovingly win them to Christ, the embodiment of all that is truly human.

Reviewed by Robert Webber, professor of theology at Wheaton College. He is the author of numerous books, including Secular Humanism: Threat and Challenge (Zondervan, 1982) and Worship Is a Verb (Word, 1985).

Looking For The Hand Of Heaven

Beyond Reason, by Pat Robertson with William Proctor (William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1985, 178 pp.; $12.95)

Most modern adults—and not a few Christians among them—would nod agreement to Santayana’s definition of miracles: “Propitious accidents, the natural causes of which are too complicated to be readily understood.”

Pat Robertson, however, is one who believes there is more to the matter than that. His new book (his first with a secular publisher) unabashedly credits God for a wide range of “extraordinary, amazing events … which typically inspire a reaction of great wonder.” To trigger such wonder, in fact, is among the popular author’s motives for writing Beyond Reason.

Reading Robertson’s book is a little like watching his “700 Club” telecast: you may not agree with everything, but you don’t feel inclined to dismiss it outright, either. The book, like much of the show, is an upbeat parade of testimonials to the power of God in people’s lives.

What Robertson and his coauthor have done is stitch together 26 contemporary miracle stories. Journalistically speaking, they are well told and generally believable; Robertson does not appear to traffic in hearsay. He cites names, places, dates, and times; he quotes newspaper reports and medical records where relevant. He has talked face to face with many of his subjects on “The 700 Club,” some of whom had been brought to faith in Christ through watching the program and phoning one of its counselors.

Of course, some readers will comment that one man’s miracle is another man’s fluke, or coincidence. After all, we have all had our fill of overblown accounts of how God allegedly saved a parking place or arranged a sale on this or that necessity. One kind of reader may frown at Robertson’s crediting God for turning a hurricane away from CBN’s transmitter tower, but be awed by the restoration of Mike MacIntosh’s LSD-soaked brain—while another might have the opposite reaction.

It is hard, however, to write off the entire book as happenstance. The reports, arranged in chapters by category, deal with general healing (six accounts, ranging from lupus to brain tumor), reversal of cancer (four accounts), survival of air crashes (two), controlling deadly storms (five), restoring minds shattered by drugs or other trauma (six), and unusual financial blessing (three).

“We find we don’t live in a closed system that can be completely understood if smart humans just work hard enough at it,” Robertson asserts. “On the contrary, the real universe is open-ended.… Things are not at all what they seem.” It is this mystifying but unavoidable characteristic that coaxes us toward the supernatural, beyond the ropes of reason. The author shows familiarity with such benchmark works on this subject as C. S. Lewis’s Miracles and essays by Robert Jastrow. The writing style, however, is for the common man or woman who wonders whether God ever really does anything spectacular anymore.

Signs And Wonders

Educated Westerners have trouble with a book like this if they insist on holding separate mental compartments for “the natural order” and “miracles” (i.e., “intrusions”). Such a dichotomy arises more from the Enlightenment than from Scripture, which views God as intimately involved in each breath and sunrise. In fact, the various Hebrew and Greek words for the miraculous, translated “sign,” “wonder,” or “mighty deed,” seek not so much to cross-examine the event as to describe its effect on human observers. (Of course God sent the manna and opened Peter’s jail; the only remarkable part was the crowd’s response.)

Occasionally Robertson risks a somewhat mechanical analysis of how a certain miracle came about (“Faith Step Two: Kris made a firmer commitment of his life to Jesus.… Faith Step Three: Kris’s entire being was filled with God’s Spirit …”). Is he proposing a set of sure-fire techniques to force miracles from God’s hand? Some may assume that, but the various lists of “steps” are too general to form much of a blueprint. “Regard these examples and the principles they reveal more as pointers to establishing a deep faith than as hard-and-fast models or rules,” he cautions.

Robertson is also candid enough to include one story about a time he insisted on a miracle—for a 12-year-old girl struck by a car in front of the church he served as assistant pastor—and did not get it. She died.

“Obviously, we can ask God for what we want. But better still that we should ask God to show us what He wants.”

All things considered, Robertson is on the side that says it is better to ask confidently for supernatural help, even expect it—and sometimes be disappointed—than not to risk asking at all. “God, of course, can do what He wants, regardless of the faith or expectations of any human being. But it’s part of His scheme of things in the universe to involve men and women in His work—including miraculous work.”

Reviewed by Dean Merrill, senior editor of LEADERSHIP journal.

Who To Obey?

Holy Disobedience: When Christians Must Resist the State, by Lynn Buzzard and Paula Campbell (Servant Books, 1984, 248 pp.; $7.95, pb).

When the late Francis Schaeffer and his son Franky agree with Jim Wallis of Sojourners on something, that something is worth noting. And the basis of this noteworthy agreement? Disagreement—or, more exactly, civil disobedience.

With activist agendas on both the Right and the Left encompassing such volatile issues as abortion and the nuclear arms race, a growing number of evangelicals are deliberating the consequences of disobeying their government, and openly espousing civil disobedience.

That is not to say that such belligerence isn’t shocking or a little threatening to many evangelicals. We may have heard of Gandhi; we may remember the great exploits of Martin Luther King in fighting racial discrimination; but, for the most part, we have not grown up in traditions where civil disobedience is discussed, let alone practiced. Holy Disobedience is a primer on the subject, providing a wide and deep historical context for understanding the reasons behind obeying God rather than man.

Authors Lynn Buzzard, executive director of the Christian Legal Society, and Paula Campbell, a practicing attorney, take their subject seriously. After introducing and attempting to define civil disobedience in general terms, they jump into the history of civil disobedience in America. They describe, in some detail, the “creative legacy” of Henry David Thoreau and Martin Luther King, Jr., and follow with a brief review of the “Christian tradition” of civil disobedience, beginning with the early church and continuing right up to John Howard Yoder, Jim Wallis, and Francis Schaeffer.

In dealing with what the Scriptures have to say about the subject, Buzzard and Campbell offer surface treatments only. They are more concerned with presenting the variety of interpretations given to such passages as Romans 13:1–7 than they are building a biblical justification for one or the other view. (This same tack is used in their discussion of legal precedents and predicaments relating to civil disobedience.)

The authors keep their objective distance from the critical question of when to disobey the state, and they do not campaign for a particular program of disobedience. They do, however, make it clear that Christians should be willing to disobey the state in order to remain faithful to God—thus implying that they are not opposed to civil disobedience.

Readers, then, who are looking to Buzzard and Campbell for specific direction on when it is okay to disobey the state will be disappointed. The “bottom line” for the authors is not a particular agenda for action, but simply an outline of several facts and principles for the Christian considering civil disobedience. The authors state their purpose this way: “… to assist in exploring the issues, examining the nature of biblical and Christian thinking (albeit in a necessarily summary fashion), and suggesting some fundamental concepts and prudential principles for Christians who are increasingly sensitive to the claims of God clashing with those of contemporary culture.”

While excellent discussion starters, the outline of seven “canons” or principles to consider before taking disobedient action against the state exposes the authors’ conservative restraint. After all, who can disagree with the first canon proclaiming that one’s basic presuppositions will shape one’s view of civil disobedience? Or with the fourth stating that not every act of government appearing to be unjust warrants civil disobedience? Indeed, the reader who wants to fight abortion, the arms race, or some other evil with civil disobedience will not find unqualified encouragement in this book.

While it lays intelligent and easily accessible groundwork on a complex subject, Holy Disobedience needs to be followed by another book that is more specific in evaluating the Christian’s use of civil disobedience as a means to an end. Furthermore, a “sequel” should try to answer some of the questions raised here but not answered. For example, we are told that a Christian’s decision to disobey the government should presuppose a Christian understanding of government and the state. But what exactly should that be? What is a just state, and how do we know when civil disobedience is called for? And if a government is legitimate and just, should not Christians promote change through legal means if they have the freedom to do so?

Also, many questions about the relation between “higher law” and “actual laws” need to be answered more fully. Should not Christians view the challenge to state law as coming from divine norms of justice calling unjust laws into question? If so, then the tension in the conscience of the Christian is not between a general “moral conscience” and particular public laws, but between the demands of justice for a just government and the actual promotion of injustice by those laws and authorities.

Finally, do unjust public laws not demand public communal responses from groups of citizens—whether those responses are legal attempts to change the laws or illegal acts of disobedience to protect those laws? If so, then why do these authors place their emphasis on individual, conscientious acts in contrast to organized, communal acts?

Holy Disobedience is neither a handbook on technique nor an argument in support of or in opposition to civil disobedience. It is, instead, a collection of timely and highly readable materials on a subject bound to loom even larger in evangelical churches in the volatile days ahead.

Reviewed by James W. Skillen, executive director of the Association for Public Justice in Washington, D.C.

West Meets East

Islam: A Christian Perspective, by Michael Nazir-Ali (Westminster, 1984, 185 pp.; $11.95).

With epic shifts convulsing the Muslim world, many Christians sense they need a basic understanding of the religion behind the turmoil. But most available books are either of the strident apologetic variety that, like a prosecuting attorney, seizes on every perceived flaw in classic Islam, or of the syrupy dialogue variety that, like a labor negotiator, can read commonalities into the most divergent positions.

Happily, this one is different. It is not a textbook introduction to Islam, but a succinct, broad-ranging survey of the religion’s background, development, and interaction with Christianity. Michael Nazir-Ali has written an evaluation that is sympathetic and critical at the same time. A Muslim convert, now vicar of Cathedral Church of the Resurrection in Lahore, Pakistan, he comes by this balance naturally: “As a Christian I accept joyfully much in the culture of Islam as God-given and good. There are, however, other aspects of Islamic culture which seem to come under the judgment of the gospel and are to be rejected by the Christian.”

The author gets right down to specifics—never pugnacious, but never pulling his punches. He deals directly, for instance, with shortcomings in Muhammad’s character, but also cautions against the mentality that always compares the Muslim prophet with Jesus. Muhammad stands up well, Nazir-Ali asserts, when compared to most other men of his time, and even of later times. And in this vein the author notes a parallel between the autocratic manner in which Muhammad ruled Medina and Calvin ruled Geneva.

Apostles And Apostates

The effect of the recent wave of Muslim fundamentalism felt most keenly by Christians in Iran, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Egypt is in laws restricting the conversion of Muslims to other faiths. Efforts have been made in Egypt and Pakistan even to impose the death penalty for apostates—but they have not prevailed. Nazir-Ali notes that the Quran speaks of punishment for apostasy, but it is clearly in the afterlife. Still, the tradition of the Prophet usually has been so interpreted that in an Islamic state Muslims would not be allowed to change their creed.

Nazir-Ali sees no relief from these restrictions so long as fundamentalists are ascendant in the Muslim world. (Iran, he says, “has chosen to go back several centuries as far as cultural mores and the law are concerned.”) But if fundamentalist economic remedies do not begin to work soon, he predicts progressive forces may yet restore more liberal and enlightened systems in these lands. This is clearly his hope.

Since the fundamentalist regimes have begun more strictly applying Islamic law, he observes, “Christian workers in Muslim countries have reported renewed interest among Muslims in the gospel of grace, forgiveness, and mercy as an alternative to the often harsh and dry interpretation of Islamic law which is being imposed upon them.”

But Christians are in error, the author says, when they claim their faith is unique in proclaiming that God loves: “The deep influence of Sufism has ensured that the Muslim too believes in the love of God. There is, however, a distinction which may still be validly and usefully made.… The Quran always speaks of God’s love for the righteous or for the believers and never of his love for sinners.”

Nazir-Ali denounces separate “convert churches” for Muslim converts, modeled on the “homogeneous unit” principle advocated by Donald McGavran and others, as “wholly against the testimony of Scripture and catholic tradition.”

Because Muslims suspect that Christians cooperate in social and educational development projects only to be able to proselytize, the author urges Christians to explain that they “do not serve simply to be able to preach the gospel, they serve because they are commanded to do so by the gospel.” It is unnecessary for Christians to “bribe” people into the kingdom since the gospel carries its own power to convince and to change. Throughout history men and women have become Christians without any incentive of material benefit and have often lost heavily in a material sense because of their commitment.

Nazir-Ali maintains that Christians who refrain from trying to persuade a Muslim of the truth of the Christian faith are leaning over backwards unnaturally. After all, he says, “a Muslim scarcely ever has much hesitation in affirming what he believes to be the truth and in trying to persuade others that it is indeed the truth. He understands this to be part of the Islamic da’wa (appeal) to the outside world.”

Reviewed by Harry Genet, director of communications for World Evangelical Fellowship.

Browsings

Crumbling Foundations, by Donald G. Bloesch (Zondervan Publishing House, 1984, 168 pp.; $6.95, pb)

Theologian Donald Bloesch describes in broad strokes and few pages the fall and rise of the church in an age of technological humanism. “It is not autonomy,” writes Bloesch in his Preface, “but conformity to the collective values of the nation-state that is championed by the new technological liberalism. It is not the separation of church and state, which has received traditional support from traditional humanists, but the enthronement of the state or nation that presents the most dire threat to the integrity and independence of the church in our time.”

An evangelical scholar of the first order, Bloesch offers little comfort to those who identify the gospel with either the humanistic political Left or the nationalistic political Right. Yet he accentuates the positive by including, among other things, a Hebrews-like litany of twentieth-century saints (political liberals and conservatives) whose lives offer models for the church in these later days. “It is the proclamation of the gospel,” writes Bloesch, “that will arouse the special ire of a secularized world. Life and words, of course, go together, but the stumbling block that will elicit the rage of the world is Jesus Christ himself and those who bear witness to him.”

That the church has not only survived such rage, but proved victorious in its midst, are both the book’s challenge and hope.

Philosophy of Religion, by C. Stephen Evans (InterVarsity Press, 1985, 200 pp.; $5.95, pb)

Built upon the obvious assumption that, despite secularist doomsayers, religion is an important force in human life and human history, philosopher C. Stephen Evans addresses questions of such cosmic significance as “Is there a God?,” “Does God influence our lives?,” and “Is there only one true religion?” He investigates the meaning and significance of personal religious experience, revelation, and miracles, and looks at the relationship of religious pluralism to individual religious commitment.

A scholarly apologetic written in a style more accessible than most, the book offers the theologically inclined an introduction to the philosophy of religion and some answers to those questions that are its focal points.

Turning Fear to Hope: Help for Marriages Troubled by Abuse, by Holly Wagner Green (Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1984, 228 pp.; $5.95, pb)

Disturbed with the church’s silence on the subject of wife abuse in Christian families, Holly Wagner Green responded with this articulate look at the complexities of domestic violence. Case histories and “reasons why” are compassionately and realistically presented in the context of such confounding questions as “How is it possible for a Christian man to be abusive to his wife?” and “Is it wrong for a Christian wife to try to escape from an abusive husband?”

Green, a specialist in human growth and development, makes an especially noteworthy contribution by devoting an entire chapter to reconciliation—a dirty word to many counselors faced with situations of abuse. However, the reconciliation talked about here is neither a blind reentry into an abusive situation nor a Pollyanna application of the faith. Instead, it is the acknowledgement of its possibility despite seemingly insurmountable odds.

Quoting the administrator at a shelter for battered women, Green writes: “We do not in any way mean to imply that we simply push the couple back together. Before husband and wife can live together in peace, the marriage must change substantially. As peacemakers we attempt to create harmony out of discord. We do not ignore or minimize conflict. We do not apply ‘Band-Aids’ over the tears. Rather we work together with the two individuals to build up their own strengths, and then we slowly and painstakingly work at reweaving the fabric of the marriage.”

Long Road Home, by Wendy Green (Lion Publishing Corporation, 1985, page length, cost unavailable at press time)

Reflections on a spouse’s or close friend’s terminal illness is certainly nothing new. In fact, books of this genre tend to be more cliched than compelling. But what Wendy Green has done here is present a lyrical odyssey taking us through her pastor husband’s diagnosis of cancer, its emotional and spiritual stress on the family, and their coping after death.

The telegraphic, stream-of-consciousness writing style employed may occasionally bog some readers down. But ultimately, this diary of deep inner emotions allows the reader to get close to Green, and to relate to those questions and doubts characterizing so much of life.

This is a spiritual song. Not of joy, but of holding on.

HAROLD SMITH