Jesus said no one can serve two masters; either God or mammon ultimately takes control. Yet despite desires to serve God, church leaders find money issues unavoidable. For some reason, God seems to have wed money and ministry, even while warning of the dangers of money’s allure. How does the church leader deal with this uneasy marriage?

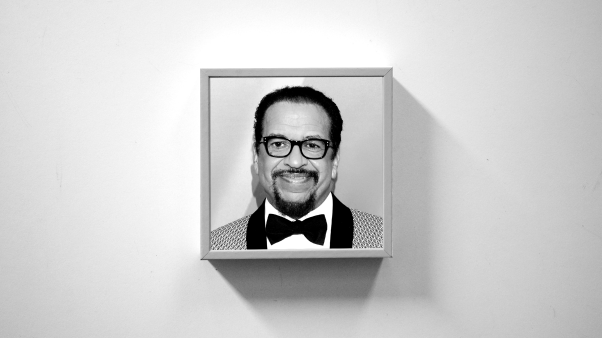

LEADERSHIP sought out a pastor who has known years of both lean and fat.

Jerry Hayner grew up in West Virginia, one of four sons of a glass-factory worker, and as he says, “We wore out the erasers on pencils because we didn’t have a lot of paper.” A basketball scholarship put him through college, and he later graduated from Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. He has pastored in Vanceburg, Kentucky; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Gainesville, Florida; and is now pastor of Forest Hills Baptist Church in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Many pastors feel guilty or embarrassed talking about money, whether the church’s or their own. Why is that?

Money seems so “unspiritual.” It’s mammon, which represents the selfishness of life. Our Christian faith accents self-denial. Money can buy you comforts, which hardly seems like self-denial. Also, Jesus was poor by the world’s standard, and he moved among the poor. These combine to make many assume there is something spiritual about a lifestyle of poverty.

Let me hasten to say I don’t agree with that concept. Money is not unspiritual. It’s a fact of life, and the important thing is what we do with it, whether it controls us or we control it.

It’s been said that money is one leading cause of ministerial casualties. How so?

Many churches today are caught up in the business model. The pastor is seen as head of the corporation, and if the annual report doesn’t show a profit, there’s panic. Many pastors are not fund raisers. It’s neither their gift nor their calling. But if the church isn’t meeting the budget, or if it isn’t providing the full program people expect, the pastor bears the blame.

I know people who are unashamed to say the first item they read in the church newsletter is the financial statement-how much money was taken in last Sunday. That’s the scorecard.

In every church I’ve been in, I’ve had people who judge me more by that standard than by my sermons, the number of baptisms, or how many ministries are offered. Money is the bottom line. It’s their measure of the church’s success.

Paradoxically, people expect the pastor to keep the church well funded, but sometimes neglect to take care of their pastor.

I’m grateful that the last two churches I’ve pastored have treated the ministerial staff very well financially, but there are still churches that believe if you keep a pastor poor, you keep him humble. And a number of pastoral casualties occur because pastors can’t afford to stay in the ministry.

One man, formerly a successful pastor, told me recently it became apparent that if he remained in the pastorate, his children would be deprived of a college education and a lifestyle that would even remotely resemble their peer group. He said, “I went through that as a son of a pastor, and I vowed it wasn’t going to happen to my children.” So he went into another line of work.

One complicating factor is that pastors, professionally, are on the level of doctors, lawyers, and company presidents. And socially, pastors are expected to hold their own with these people. But the salaries are rarely comparable. So when you go out to eat at a nice restaurant with some of these people, for them it’s pocket change; for the pastor it takes three months to pay off the MasterCard bill.

Fortunately, this is changing. Churches are becoming more realistic, much more human. Part of this is because churches are discovering the high cost of replacing pastors.

When I left one church in 1973, for instance, I was making $14,000-counting everything including the potatoes we were given! Much of that money, of course, I never actually saw because it went into insurance or pension. I’d been there six years, and the church had grown from less than two hundred attenders to nearly five hundred, had bought ten acres of suburban land, had paved the parking lot and remodeled the building-and my wife, Karen, and I were virtually living at a poverty level. We never were able to afford a car with a radio.

The point of all this isn’t self-pity, but simply to point out that after I left, they couldn’t find anyone qualified who would accept the job at that salary. My successor came at $27,000. The church was forced to upgrade.

Occasionally pastors are given gifts by generous members of the congregation. How do you handle that when you know you’re unable to reciprocate?

It’s true. You can’t give back at their level.

In Knoxville, Karen and I had friends who were almost like parents to us. They were older and had no children, and they gave us season tickets to University of Tennessee sporting events each year. They gave us steaks, and at Christmas they’d give us a $500 check “to buy something for the children.” They were gracious people.

How do you pay back people like that? You certainly can’t match their gifts. But we did want to give something that conveyed our love and appreciation, a gift that showed thought.

For instance, they enjoyed serious Bible study but weren’t aware of all the resources, so one Christmas we gave them a Bible dictionary set. It certainly didn’t match their gifts, but it was appropriate and had meaning for them. I wrote a note of appreciation in the front, and they genuinely seemed to enjoy that gift.

How important is the financial package in deciding whether to accept a church’s call?

Obviously a major factor, but not the most important. The hardest career decision I ever made was turning down a call that would have meant an $18,000 pay increase. That church had wealth and great facilities-family-life center, gymnasium, offices, grounds, sanctuary, education space, retreat center in the mountains. It was first-class. My wife and I visited the place three times trying to convince ourselves to accept that call, but neither of us could come to peace with it, even though it would have put us in an economic bracket that would have made it easy for us to put our daughter through college.

Why did you say no?

You have to understand who you are and what your ministry is. That’s the bottom line. In considering any change, I ask myself two questions.

First, can I motivate these people? I’ve got to feel I have something to give to a prospective congregation. And if I get to the place where I feel I am no longer motivating my present congregation, if I’m a voice they’ve heard so much that it’s too familiar, and if I feel this way over a period of time-not just on Monday after a bad Sunday-then I’m willing to consider a call elsewhere.

Second, do these people motivate me? If my present congregation no longer causes me to dig in and work hard, and if they are not making me excited to get up in the morning, that at least opens the door for me to consider another place of service, should one come along.

In this case, the new church did not present me the challenge the church I was pastoring offered. It didn’t motivate me. I was still motivated where I was, and I felt I was at the peak of my ability to motivate the people there. I could not in good conscience leave simply to take a higher income.

Frankly, I’ve never regretted that decision.

What are the consequences of using finances as a measurement for ministry?

Ultimately, despair. The financial measuring stick is almost always used to compare our situation with someone else’s-either another person’s salary or another church’s budget. And there will always be someone who makes us look small.

It’s tough to graduate from seminary and see college graduates being pursued by IBM or Eli Lilly or Burroughs for tens of thousands of dollars more than you’re making. If you see life through financial lenses, it’s hard to accept a call to a small church in Oklahoma, where some of the other pastors in town have never been to seminary.

On the congregational level, with the corporation mindset, you judge churches by their prestige, size, or wealth. And again, you can never win that game! People in your congregation will always tell you about another church in Houston they just heard about that has some fantastic ministry, and unless you start it here, your church is deficient.

It breeds despair and disillusionment.

So the effect on ministry is a quenching of your spirit, your motivation?

Yes, but it also causes ministers to begin pursuing things they shouldn’t just to satisfy the people who are on their backs.

Every church, for instance, has certain influential people who want you to really push tithing. They’ll take you out to lunch and say, “Pastor, we’re really concerned that you’re not preaching enough about money. We’re not making budget like we ought. We’re not able to give as much to missions as we’d like. You need to come down hard on that.”

Now suppose the pastor is focusing this year on pastoral work with families, with hurting people, or with some issue in the community. The pastor has to make a choice: Will I continue on that track? Or am I going to take their track?

Several pastors I know have given in to that pressure and said, in effect, “If that’s what it takes to survive, then that’s what I’ll do.” So every sermon has its jabs, every decision is weighed by its effect on giving patterns. Consciously or subconsciously, they feel they have to produce a profitable corporation.

Even with the stereotype that says, “The church only wants my money,” you still find church members wanting you to ask for more?

Not the rank and file. It’s the financial watchdogs who put the pressure on, and usually that’s only a few individuals.

People outside say, “Every time I go to church, they talk about money.” Those are voices crying in the wilderness. The other voices are crying in your board room.

They’re probably not saying, “Preach to us about money.” Isn’t it “Preach to them”?

True. And with that constant pressure, I’ve had to answer to myself and to the Lord. I tell myself, They can take my job, but they’re not going to get my soul.

I told someone the other day, “Look, every time I step into that pulpit and see twelve hundred people, I know some of them are hanging on by a thread, just trying to survive, and this service gives them hope for another week. I absolutely refuse to make every Sunday a pitch for money.”

I remind myself that the purpose of the church, financially, is not to accumulate as much money as possible but to give away as much as possible.

So how often do you mention money in a sermon?

I do my share. We have our times and seasons during the year that lend themselves to focusing on a person’s stewardship. But I have to resist the steady pressure to do more.

In the Southern Baptist Convention, for example, we have four major mission offerings a year: home missions, foreign missions, world hunger, and state missions. Each promotion lasts a month and comes complete with literature, envelopes, messages, articles in denominational newspapers, everything. The denomination really pushes it, and all the churches set giving goals. If you don’t reach the goal, some think you’ve failed.

In my first couple of years in my present church, either the goal was too high or the people dragged their feet or something. I was doing some kind of promotion every Sunday that month. When the four weeks ended and we hadn’t reached the goal, I had to extend the promotions another three or four Sundays until the goal was met. It was taking eight weeks to finish one missions offering. Multiply that by four, and thirty-two Sundays a year were spent raising funds-and we hadn’t even mentioned our own church budget!

I finally had to take a stand: “We will give each appeal four weeks. That’s it. After that, nothing more will be said in the bulletin, newsletter, or pulpit.”

The upshot has been that we have reached most of the goals, but not because of extended pulpit appeals. Those concerned about the goals talk privately to people, which is fine with me.

I tell our finance committee, “I can’t criticize this church. Our income has gone from $500,000 to nearly $1 million in four years, and while we’ve had healthy growth in attendance, it hasn’t been in proportion to our financial growth. That money has been coming from the same people. And when people increase their giving like that, I’m not going to berate them for not doing more.”

Has it been a struggle to meet such a rapidly growing budget?

I’ve been criticized for making budgets too high. My philosophy, however, is that the budget ought to cause you to stand on tip-toe to reach it, but if you’re standing on tip-toe, you ought to be able to reach it. In other words, it ought to be a challenge, but a realistic challenge.

We’re running behind budget right now, and we may not reach it this year. But we’re not pulling out our hair, because we realized we were setting it high-$110,000 more than last year, an 18 percent increase. And our budget has enough flex with contingency funds and optional maintenance items that we won’t cripple our ministry.

Among Southern Baptists, 10 percent is the normal increase for a healthy church. Anything more is taking a risk. And we’ve had increases of 14, 18, 22, and 18 percent in the last four years.

In years past, if we didn’t make budget, people felt like failures. Now we look at it this way: “Even if we didn’t raise it all, we still gave $90,000 more than we did last year. And that’s a successful year.”

Does the congregation know your own level of giving?

I’ve told the people that ever since my first summer job at J. C. Penney as a high school sophomore, I have tithed. I don’t say that to brag; it was simply the way I was brought up. My wife and I believe the Lord deserves at least a tenth of our income, and in addition, we contribute to the seminary where I graduated and to other causes we feel are worthy.

Recently, during a special stewardship drive, I had to give public testimony about how my wife and I planned to increase our giving over the next fifteen years. I like the denomination’s concept here; we don’t emphasize the amount of the increase, but the percentage of increase.

For instance, we don’t care if you give 5 percent or 30 percent. If people haven’t tithed before, many of them are terrified at the thought of giving away 10 percent of their income. So we might ask people to increase their giving by l/2 percent of their annual income. When they divide that number by fifty-two Sundays to see what their weekly increase will be, they realize it’s not all that much.

If they increase by l/2 percent each year, after fifteen years even nontithers will be giving 7l/2 percent.

What did you and your wife say you would do?

Our plan is to get up to 16 percent in that period. Right now we’re giving close to 12 percent. For the first five years, we’re going to add l/2 percent per year, and then reevaluate at that time. I want to set an example of steady increase for at least the next five years.

Do you teach people to base percentages on take-home pay, gross salary, or total pay package?

Everyone’s situation is so different. One person has to cover his insurance, social security, and annuity out of his take-home pay. Another person has that paid by the company. So I don’t get into that.

When someone presses me for specifics, I say, “If you need a figure to work from, just start with your take-home pay.”

When you come up against a financial problem in the church, where do you go for help?

Every church has its “E. F. Huttons,” the people who, when they talk, everyone else listens. When I come to a church, these are the people I look for first. And when we face a problem, I seek them out.

How do you spot the “E. F. Huttons”?

I observe business meetings, committee discussions, and informal conversations. I notice the names people invoke. In business meetings, you’ll hear a lot of ideas batted around, and then someone will say, “Well, it seems to me . . .” After a few more minutes, the vote is taken, and it goes that person’s way.

They’re usually not the first to speak. They’re not ones to wave flags or call attention to themselves. But if you watch, you’re able to see their influence. Many times they’re people of great spiritual sensitivity, which is what makes others in the church follow them. I try to cultivate a relationship with these people.

What are some of the things you’ve gone to them for?

In one church, the previous pastor had been highly conservative in financial matters. No budget could be higher than last year’s income. Now that’s safe! For years he’d always reached his budget because, in reality, he’d reached it the year before. It’s like putting your dart on the wall and drawing circles around it. You always hit the bull’s eye.

My philosophy is a bit different. He ran three downs up the middle, and if he didn’t make it, he punted. Now I won’t pass from my own end zone, but I’ll pass from my five-yard line. I’m willing to take a few more risks.

When I went to that church, I’d been led to believe the church was looking for a passer, a more progressive signal caller. That assessment was accurate for 80 percent of the congregation, but not for the heart of the church, the decision makers.

So I looked for my E. F. Huttons, and I found them. They were people everyone seemed to love dearly. I enjoyed getting together with them and talking about the past-how the church got started-and then I’d ask, “Where do you think the church should be going?” We developed a good friendship.

Then an issue came up. The church was landlocked and really needed to buy some property. Previously, the church had rejected purchasing that property. Now we had no choice: either buy that property or stop growing. I, along with most of the younger members, was for the purchase.

But some of the 20 percent saw me as the villain who was going to lead the church into financial ruin.

So I went to my E. F. Hutton, told him what was being said, and asked for his help.

He said, “Don’t you worry about it.” He was director of the adult Sunday school, and he stood up the next Sunday and reminded them of their great days of faith when they launched out without knowing where they were going and without great resources. He pointed out how the Lord provided, and he said, “Now this is a new time, and we have new challenges. Let’s get behind this program.”

End of chapter. The resistance evaporated.

Some people might call these “games” you have to play. I don’t call them games. It’s reality, learning to deal effectively in human relationships.

What do you do when the resistance remains?

I don’t argue. As I told the deacons one time, “Even if the Lord appeared visibly to me and told me our church was to do certain things, if you didn’t agree to do them, I wouldn’t do them. I’m not going anywhere without you. If you can’t support the program, it’s going to die right here in this room, because I won’t fight you on the floor of the church. If you who are elected spiritual leaders of this church cannot run with the program and believe in it, then I’m not going to do an end run.”

Have you ever had to do that?

Oh, yes. After I went to one pastorate, we had a committee examining the possibility of buying a computer to help us with our financial and visitation records-things that would help us manage a large church effectively.

Well that was new stuff for a lot of people who still used pencil and paper because they didn’t trust a hand calculator to balance their checkbooks. Talking about a computer was like launching a space ship from a horse and buggy.

We voted on it and won. That is, we got the numbers: 70 percent for, 30 percent against. But I told the congregation the next week that we weren’t going to buy the computer. Afterward some of the 70 percent criticized me: “When are you going to let the majority win around here?”

I said, “This isn’t a majority/minority thing. Why risk the fellowship in the church over a silly computer? Maybe we’re premature.”

We did some more research, even changed computer companies, came back about four months later, made another presentation, and received nearly 100 percent approval.

Often it pays off to wait your time.

If the church is in good health and the people aren’t fighting with each other, time generally will let all of them move along with you. If they are fighting with each other, however, nothing you can do is going to help, because they’re going to vote against each other, not for or against the issue.

What do you know now about money that you wish you’d known at the beginning of your ministry?

I think I’ve learned to be a little more realistic than idealistic. Early in my ministry I thought if you could just present the Great Commission and have your planes and ships lined up, people would automatically want to get to them. I’ve learned you have to be realistic in developing both budgets and the feelings of people. You have to adjust your expectations.

I don’t claim for a half second to be a financial wizard; that’s not my gift. But I try to know enough not to be naive.

And I’ve tried to put round pegs in round holes-to put people with capabilities in leadership positions and let them know this is their gift and this is where God has placed them in this church at this time for this purpose. After all, the church isn’t my church. Under God, it’s their church, too.

* * *

NOT IN IT FOR THE MONEY

As I was finishing seminary, I met with the pulpit committee of a Baptist church in South Carolina. They were considering me as an associate minister, and they seemed to like me. Soon we were talking specifics.

The chairman of the finance committee looked at me and said, “Now we don’t have much money, and we’re deeply in debt. We want to know, Jamie, how little can we pay you and still have you come?”

That put me on the spot. They didn’t know it, but I wanted to be in ministry so bad, I probably would have paid them to work there. Nevertheless, they wanted an answer, and I didn’t know what to say.

I asked for some time to consider

I went back to Fort Worth and talked with my pastor, James Harris.

“They want me to set my own salary, but as low as possible,” I said. “What do I tell them?”

“You tell them you will come for whatever they want to pay you,” he advised. “And that means you will live at whatever level they choose. If they want you to wear the same pair of pants every day for the next year because you can’t afford to buy another, say you’ll do that. And if they want your wife never to go to the hairdresser because you can’t afford it, she’ll never go to the hairdresser. Tell them they can choose the level, and you’ll live at that level.”

That seemed a wise answer, so I went back and told them what Dr. Harris had coached me to say. I waited for their response.

“Fine!” said the committee chairman. “That means you’ll come for $3,500 a year”-which meant I couldn’t buy a new pair of pants and my wife would see no hairdressers!

We lived in the poverty they imposed, but within six months I was made pastor, and gradually we began to prosper.

When I look back on that situation, I see how God honored our commitment. Our hearts were right. We were willing to go. I wanted to minister, and I was not ministering for money.

I never have.

-Jamie Buckingham

Tabernacle Church

Melbourne, Florida

Copyright © 1987 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal. Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.