For more than fifty years, those wanting to keep an eye on trends have turned to the Gallup Poll. It has long supplied reliable data on social, political, and economic changes-and religious ones as well.

The man responsible for taking this religious pulse, who saw spiritual attitudes as a societal vital sign long before religion was front-page news, is George H. Gallup, Jr., president of the Gallup Poll and executive director of the Princeton Religion Research Center, both based in Princeton, New Jersey. Gallup’s father pioneered the science of survey research, scoring a coup with his prediction of Roosevelt’s victory over Alf Landon in 1936, and son joined father in 1954.

But George Gallup is more than a household name; he is a committed Christian seeking to keep church leaders informed about significant factors of public belief and practice, pressing to find data churches can use to make positive changes.

LEADERSHIP editors Jim Berkley and Kevin Miller journeyed to Princeton to question the master of questioning on the changes facing pastors.

You once planned to enter the ministry. What led you into public opinion research instead?

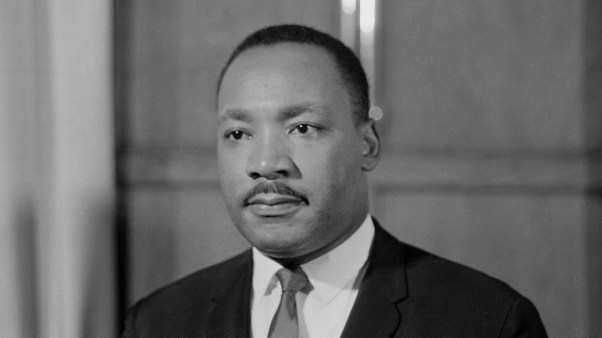

I majored in religion at Princeton University and intended to go into the Episcopal clergy. Toward that end I worked one summer in a church in Galveston, Texas. It was a black church, with a white rector for the first time in nearly one hundred years. My job was to help him run the summer Bible school, the baseball team, and activities like that.

It was a great experience. Indeed, if I were yet to go into the ministry-and I sometimes still long for it-I would want to serve in such a setting. The rector I worked with was instrumental in breaking down racial barriers in the church, and it meant a lot in my life to see that.

But while weighing the choice of the priesthood or survey research, I realized that in a way my father’s field provided a lot of things I was looking for in the ministry. It gave me a way to help people, by raising the level of information and finding out what the public’s needs are. More specifically, it provided an opportunity to help churches of all denominations determine how to reach people better.

Surveys are an invaluable guide to show pastors and leaders the church’s levels of belief, knowledge, and practice, which can help pastors deepen beliefs, raise the level of practice, make it more meaningful, and reach out to new people.

So polling is, for you, a ministry?

I first realized that when I was with those people in Galveston. They are remarkable people, but how do you give them a voice? Through surveys. It’s wonderful to give people a voice.

Surveys can penetrate deeply and give people a chance to be heard or to commiserate-a chance to be. People get to talk about their church, their way of life, their country. Giving them that chance says, “I care enough about you to want to know what you think and feel.”

I do have to wear two hats in a sense: a pollster’s hat and a Christian’s hat. But speaking as a Christian, I think our duty as a church is to create a setting that allows a person to have a personal encounter with Jesus Christ. And I think understanding people’s attitudes helps make that possible.

If you were to become a pastor, what would be the first thing you’d do?

I’d want to create the feel of an extended family in my church. People everywhere are hurting, and the church, as an extended family, can help hurting people.

But the first thing I would do is take a survey. I’d want to find out where people are in their religious lives and what are their potentials and frustrations. Then the next step would be to try to encourage everybody to get involved in a Bible study or a prayer-fellowship group.

My wife, Kingsley, and I are in a couple of small groups. Both are made up of a wide variety of people, and that’s the strength of the group experience. We’re from diverse backgrounds, but we meet together in a spirit of openness and love.

Some people would say that religion is a private, internal matter that can’t or shouldn’t be scrutinized by research. How would you respond?

I conduct research into religion for three reasons. One is sociological. The spiritual or religious element in American life is a key determinant in our behavior-in some respects more so than traditional background characteristics such as education, political affiliation, and age. If you want to understand society, you need to understand the religious dynamic.

Second is a practical reason: If ministers want to minister to people, they need to know what the challenges are, what they have to do. Surveys can help them focus their efforts.

Third is the religious reason. If there is a God looking over us, and I believe there is, then to bring us closer to God, we should do everything possible to examine the relationship between God and humankind.

We have been focusing our efforts in the area of religion more and more. Religion is the last area for pollsters to explore in depth. Political and economic beliefs have been explored ad nauseum. But not much has been done in the area of religious research. I think many exciting discoveries lie ahead as we explore the spiritual life of people around the world.

What do we know about spiritual life, and what remains to be discovered?

We don’t know an awful lot-except that spiritual experiences are very common. For example, in one of our surveys we found that about 40 percent of Americans have had an unusual, life-changing experience. The British recently found roughly 50 percent having this kind of experience.

So that brings up questions: What are the common elements of these experiences? What brought them about? How are they changing lives? The early evidence indicates that lives are being changed in a more ethical direction. Or for these people, life has more meaning. They are less fearful of death, or more eager to reach out to others.

Thus it becomes important to examine this experience and determine how it can be encouraged-not in an artificial way but in settings that will allow these spiritual experiences to happen, since they are life changing in a positive direction.

Up until now, it seems, our emphasis in the church has been on “the day I found Christ.” I’d like us to look a little more at the day after-what do you do with this experience?

Have any of the results of your polls truly surprised you?

Oh yes. I was surprised at the high proportion of people who have had spiritual experiences: four in ten. The proportion who believe in a living Christ surprised me. I thought people would be thinking of Jesus Christ more in a historical perspective, but 64 percent express certainty that Christ rose from the dead and is a living Presence. As a Christian, I find this very encouraging.

I’m amazed, however, at the low level of Bible knowledge. It’s shocking to see that only 42 percent know that Jesus was the one who delivered the Sermon on the Mount.

And I think the fact that nine in ten Americans are not deeply committed Christians is worthy of concern.

What do you mean by committed?

We use a list of ten questions that deeply committed people of all denominations would agree to totally-such things as believing in the divinity of Christ, or believing one’s faith should grow, or trying to put faith into action on behalf of others. These are the givens, the very basics. We have people respond to each of these on a four-point scale: strongly agree, agree somewhat, disagree somewhat, or disagree strongly. Taking all the people who say “agree strongly” on the ten questions, we arrive at about 10 percent. On that basis we have labeled them the highly spiritually committed.

Then we looked at those people in terms of volunteerism, how happy they are, tolerance, concern about the family. That’s where the exciting discoveries are, not with the churchgoers or the people who even say religion is very important. You have to go deeper.

What have you been able to discover about this committed 10 percent?

These people are much more concerned about the betterment of society. They’re more tolerant of other people. They are more involved in charitable activities. And they’re far, far happier than the rest.

These factors are especially interesting sociologically since these people tend to be in what we call “downscale” or lower socio-economic groups.

Downscale people typically are less involved in charitable activities because they have less time, less tolerant because their level of formal education is lower, and less happy for obvious reasons. Because they go against the grain for their socio-economic group, they really stand out. They are a breed apart, the truly spiritually mature.

If the numbers of these people can be increased, they will have a disproportionately powerful impact on society.

That’s why I’ve tried to develop commitment scales to put calipers on the spiritually committed segment of the populace. I hope to write more about these people, because this segment is going to make a difference in the future.

With people like these, the church is going to change from the bottom up. It’s not going to be pronouncements, conferences, strategies from the top, it’s going to be people on the grassroots level bonding together and inspiring the church.

That’s a rather radical proposition. Leadership won’t come through the leaders . . .

I think it will trickle up, although it will probably be a result of both factors-from the top down and from the bottom up. The most fervently committed persons are generally from the downscale groups, but the influence of these highly committed Christians moves back up into other groups.

How much do people’s stated opinions truly reflect their behavior?

In view of the fact that religion does not appear to be creating a more loving society, I’d have to say “Not much.” Something is wrong with the way religion is being practiced. It doesn’t seem to be working in the broad sense. We’re still beset with many problems, so there is apparently a gap between belief and action.

My friend Terry Fullam, rector of Saint Paul’s Episcopal Church in Darien, Connecticut, says that true believers are people who act upon their belief. It’s as simple as that. And as difficult.

In a survey we did for the Christian Broadcasting Network called “Twenty-four Hours in the Spiritual Life of Americans,” we concluded that much of religion, unfortunately, is superficial-“feel-goodism.” Prayer becomes mostly petition, and the Bible is not approached in a meaningful way. People want the fruits of faith but not the obligations. They’re not willing to take up the cross. As Anglican bishop Michael Marshall puts it, “People are following their own agenda and not Christ’s.”

How reliable is church attendance as a predictor of behavior?

There’s little difference in ethical behavior between the churched and the unchurched. There’s as much pilferage and dishonesty among the churched as the unchurched. And I’m afraid that applies pretty much across the board: religion, per se, is not really life changing. People cite it as important, for instance, in overcoming depression-but it doesn’t have primacy in determining behavior.

Recently for CBN, we asked a series of questions on whether people rely more on human reason or on an outside power, such as God, for moral guidance and for planning for their future. More opted for human reason than for God, although less so among evangelicals. That shows that whatever people say about their beliefs, when they get right down to it, they are not totally prepared to trust God.

You’ve been polling for thirty-four years. What major changes in the church have you witnessed during that time?

The fifties were a boom period, and by that I mean that there was a lot of church building, religious book sales were going up, and church attendance was higher than it is today. Church membership was higher. People were placing great importance on religion.

Beyond that, however, it’s difficult to comment about commitment levels, because only recently have we started to develop scales that measure deep commitment. On the whole, 1950 was far different from now in terms of surface indicators, but commitment is harder to gauge. It might have been deeper, but we don’t know.

What other changes are quantifiable?

In terms of church involvement, there has been measurable change. Back in the late fifties, a much higher proportion of people said religion was very important in their lives-about eight out of ten. Now it’s down to five or six in ten, so there’s been a big drop, which came mostly in the mid sixties to the mid seventies.

Then, about ten years ago I picked up indicators of a revival of interest in religion. But that revival didn’t necessarily translate into dramatically climbing attendance or membership.

Religious interest still seems to be growing. When we polled for CBN on the question “Are you more interested in religious and spiritual matters than you were five years ago?” the majority said definitely yes. Bible studies and prayer-fellowship groups have grown. So increased interest is not necessarily seen in attendance or membership-that’s been remarkably flat-but it is seen in other religious activity.

What happened to that great evangelical surge of the late seventies?

It was a great surge of interest in and awareness of evangelicals. In terms of numbers, there hasn’t been any great growth in the proportion of evangelicals as far as we can tell. But evangelicals have been more vocal, more active, more visible. That’s given the perception that there’s been a huge surge in the evangelical movement.

Is church life significantly different now from what it was in the fifties, or are our perceptions colored by nostalgia?

The intensity of life was always present-the sorrow and human problems and all-but there’s a whole new complex of issues now, such as the drug issue. The pastor is called on for a much more active role in dealing with problems like divorce or alcoholism or pornography or other sex-related problems like disease and unwanted pregnancies.

How has people’s confidence in the church changed during the same period?

I can go back only about fourteen years, because that’s when we started a regular measurement of confidence in religion. Nothing much changed between that first measurement in 1973 and July 1986. But then confidence started to turn down, and it has taken quite a slide since then.

I think part of it-and this is speculation-was the discomfort over the relationship between religion and politics. And then, of course, the trend downward was accelerated by the scandals of 1987. They have given a black eye to organized religion as a whole. Frankly, all the squabbling and the chastising of one another has not enhanced religion’s image one bit Maybe some of it has been necessary, but it doesn’t sit well with the public. The damage may be only short-term, but I suspect it’s going to be difficult to recover from fully.

In another sense, perhaps the unveiling of a scandal can be for the good. It’s house cleaning, and that’s all to the good.

Is change occurring in the church at a greater rate as time goes on, or do we just seem to think that change is accelerating?

Futurists say change comes about at an accelerated rate. After all, things that took centuries to change now change in a matter of decades or years, so in that sense, change has speeded up. Technology certainly seems to be exploding.

But public attitudes are different from technology. Basic attitudes don’t change at that rate. They tend to change much more slowly.

How does a local pastor deal with the accelerated change around him or her?

I may sound hung up on surveys, but in order to find out what’s happening, you need to poll, even every year. What are the priorities? Where do people see improvement made in the church? Is your outreach plan working? Things like these can be monitored. That’s one way to keep on top of events.

Often it will take a pastor years to determine the level of knowledge in the parish: What are people doing about their faith? Do they know how to pray? Does the Bible have any meaning for them? Do they share their faith? What do they believe about God? Finding this information informally consumes time, and you still don’t know for sure.

Maybe mine is too mechanistic an approach, but I want to know exactly where people are in these areas. What are their reasons for believing or not believing? Are they having trouble with their prayer life? Is it meaningful? Is it something they want to keep doing? Are they reading the Bible? From our studies, the Bible is clearly not being read. It’s revered, but not read.

So you would validate your informal reading of the congregation’s pulse with a more formal poll?

Always. Often the pastor is surrounded by active people who are the hard workers. They may give the impression that things are better than they are. It’s easy to miss the attitudes of the majority. In the same way that politicians can get terribly misled by everybody around them saying, “You’re wonderful!” pastors may pick up a misleading perspective of the church.

As effective as surveys are, what are their limitations?

To borrow from the political world, surveys are a good way to inform leadership. They’re a source of information. But they should not be the controlling factor, because a leader is to lead, not follow public opinion.

A leader will want to assess the information carefully, because, after all, the survey is the parishioners talking to their pastor. A leader would be committing a great error not to be attentive to what people need and want. But he or she also needs to use personal judgment.

How is public opinion changed?

It really doesn’t change very quickly without profound developments or events. For example, the Tet Offensive rapidly turned public opinion against the Vietnam War. People felt the war was unwinnable after that.

To be more specific, how can a pastor shape opinion toward change?

He or she can leave. (Laughter)

Seriously, let’s go back to the bottom-up theory. Really it’s not the pastor in charge of the church; it’s Jesus Christ. Everybody is a servant of Christ, and maybe he is speaking just as importantly through the laity. That’s why I believe in small fellowship groups. They have a correcting mechanism: If somebody feels God spoke to him, maybe God did. Maybe the change is necessary. But still the person has to convince others about the plan.

What’s the pastor’s role in change?

Certainly pastors are key players. They set the tone. But the leadership comes not only through them; it can come from people in cell groups who are constantly praying and seeking God’s will. There’s power from there, too, as well as from the top.

When pastors want to bring change into a church, how fast can they move?

Maybe it’s naive to say this, but I think it can be done quite quickly if they concentrate on getting groups together and finding good leaders to handle each of those groups. There’s tremendous power to sustain the church if you start with a good nucleus and move out through groups.

Americans are among the loneliest people in the world. We need to reconnect. In the church we’re beginning to rediscover each other and come together and bond. I think it’s the best thing that can happen to this country.

Earlier you said that attitudes change very slowly, and yet now you are saying that within a church some changes can be made rather quickly. Why is that?

You always have to allow for the Holy Spirit. The Spirit is often ruled out when people plan strategy. With the Holy Spirit operating, things can be done in a miraculous way and done quickly.

Since society is constantly changing, how far ahead can churches realistically plan?

Well, on a totally visionary level, an ideal wish list, you can dream ten or twenty years hence. But for a game plan, I don’t think churches can plan much beyond five years in most cases.

Let’s look toward the future. What changes will pastors face in the next decade or so?

I think sex-related issues-artificial insemination, abortion, premarital and extramarital sex, homosexuality-will be enormously important. The sexual revolution was so profound that I don’t think the pendulum will ever swing back all the way to the Victorian frame of mind, even if it does swing back a little.

We will still need to do a lot of talking about abstinence. Our society’s emphasis has been that you should be totally free; if you don’t do anything you want to do sexually, you might somehow harm your psyche. Because of this line, it is important for churches to emphasize restraint.

And another issue, without question, is the moral dilemma surrounding gene splitting. There’s also the problem of divorce and the problems of drug and alcohol use. And the whole area of child abuse is going to continue to be a problem. It’s some of these immediate problems, close to the church’s door, where we can step in and make a big difference.

The continuing breakdown in ethics and morality worries me. Materialism is one of our root problems in this country. We’re an addicted society, if not to drugs, then to overeating, to sex, to money, to cars, to owning. There’s far too much emphasis on having rather than being.

People’s hearts seem to be in the right place. Polls show that they put personal aspects of their life ahead of material aspects. They put their family ahead of possessions and getting ahead of the world, and that’s encouraging. But I think we’re overwhelmed with the allurement of and attachment to “the good things of life.” The church has a big challenge in fighting that continuing battle.

With reams of data about massive social problems, how do you keep from getting discouraged?

I think of the encouraging trends I see.

One is the great respect for education. Whether they pursue it or not, nearly everyone seems to put a high premium on education.

Another is our tradition of volunteerism. The proportion of people involved in volunteerism is growing, and volunteerism is important to the stability of our society.

Third, and the most important, is the spiritual dimension of Americans. It is seen in the volunteerism, much of which is religiously motivated. If somehow the importance of religion were to decline in this country, our country would be badly hurt.

The spiritual resilience of our country-it’s still there even though culture seems to be winning out over religion in many ways-gives me hope. I think there are enough people spiritually on fire to bring about change.

My wife and I attended the International Conference for Itinerant Evangelists in Amsterdam, led by Billy Graham. To see those evangelists, ten thousand strong, from all over the globe, joining in praise to God was one of the most moving events in our lives. The courage and commitment of those people is remarkable. In fact, we learned that three of the participants were martyred upon returning to their countries-just for having attended the conference.

They are examples of the highly spiritually committed. So you can see why I’m eager to pursue that research. I think there will be some valuable discoveries there that could be applied to help other people meet our Lord.

Copyright © 1987 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal. Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.