Saving The Preborn And Pulling “Human Weeds”

Suffer the Little Children, by Mark Belz (Crossway Books, 177 pp.; $7.95, paper). Reviewed by Guy M. Condon, executive director of Americans United for Life.

Many have noted the similarity between the mounting efforts to block the doorways of abortion clinics and the now-revered tactics of the civil-rights movement. Not surprisingly, the comparison irks abortion-rights leaders, such as the National Organization for Women’s Molly Yard, who calls prolife direct activism a “right-wing charade of harassment and terrorist action.”

More surprising, however, is the conservative Christian establishment’s tendency to discredit direct activism as a worthy expression of prolife concern. Yet, ironically, this may prove the most significant aspect of the comparison. The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., also was forced to defend his tactics to his fellow black Christian leaders, who feared that civil disobedience would hinder the movement. Many prolife leaders are reacting to direct activists, often publicly, in the same way.

Because of the emerging potential for infighting and the need for understanding, if not coalition, Mark Belz’s Suffer the Little Children has come at a timely moment.

Belz, who heads a St. Louis law firm and holds the master of divinity in addition to his law degree, has written a cogent treatise on prolife direct action in distinctly Christian terms. His work constitutes an effective integration of philosophy, law, theology, and courtroom testimony. That he has been arrested and has legally represented others in the prolife struggle lends authenticity to his treatment.

Belz explains the nub of the controversy by saying, “Evangelicals want both respect for life and respect for authority, and at the door of the abortion clinic, these values collide.” Focusing on the unborn child whose mother is heading for an abortion, he argues that “while Roe V. Wade is the law of the land, the last thing in the world that the unborn child needs, at this point in time, is a law-abiding citizen.”

Belz will rattle the psyches of some who rely on Romans 13—where Paul calls Christians to submit to governing authorities—for their final word on civil disobedience. He reminds us that the Hebrew midwives in Exodus disobeyed the order to kill the baby boys born to Hebrew women in Egypt. Moses’ parents, Obadiah, Shadrach, Meshach, Abednego, Daniel, and Peter are also on the list of the civilly disobedient. If the section on biblical precedents doesn’t soften attitudes against civil disobedience, the chapters on Christian involvement in the Underground Railroad and Nazi resistance might.

Whether or not readers are swayed by his arguments, the testimonies of the direct activists who have undergone arrest, imprisonment, disemployment, and estrangement make for compelling reading. Christy Anne Collins, for example, has been arrested 28 times. When she appeared for sentencing in 1988, she told the judge, “You cannot rehabilitate people from resisting evil.” She added, “Most of the people sitting in the front of this courtroom earn their living from the abortion industry. If I did to an animal what this court sanctions their doing to children, you would call me mentally deranged.”

Unfortunately, Belz has a tendency toward overstatement. Moreover, he could have portrayed both child and mother as victims of the abortion system, instead of defining the mother as the killer of her child. That could unnecessarily distract some otherwise sympathetic readers.

For those who want to explore prolife direct activism from a specifically Christian vantage point, Belz’s book will prove a worthwhile resource.

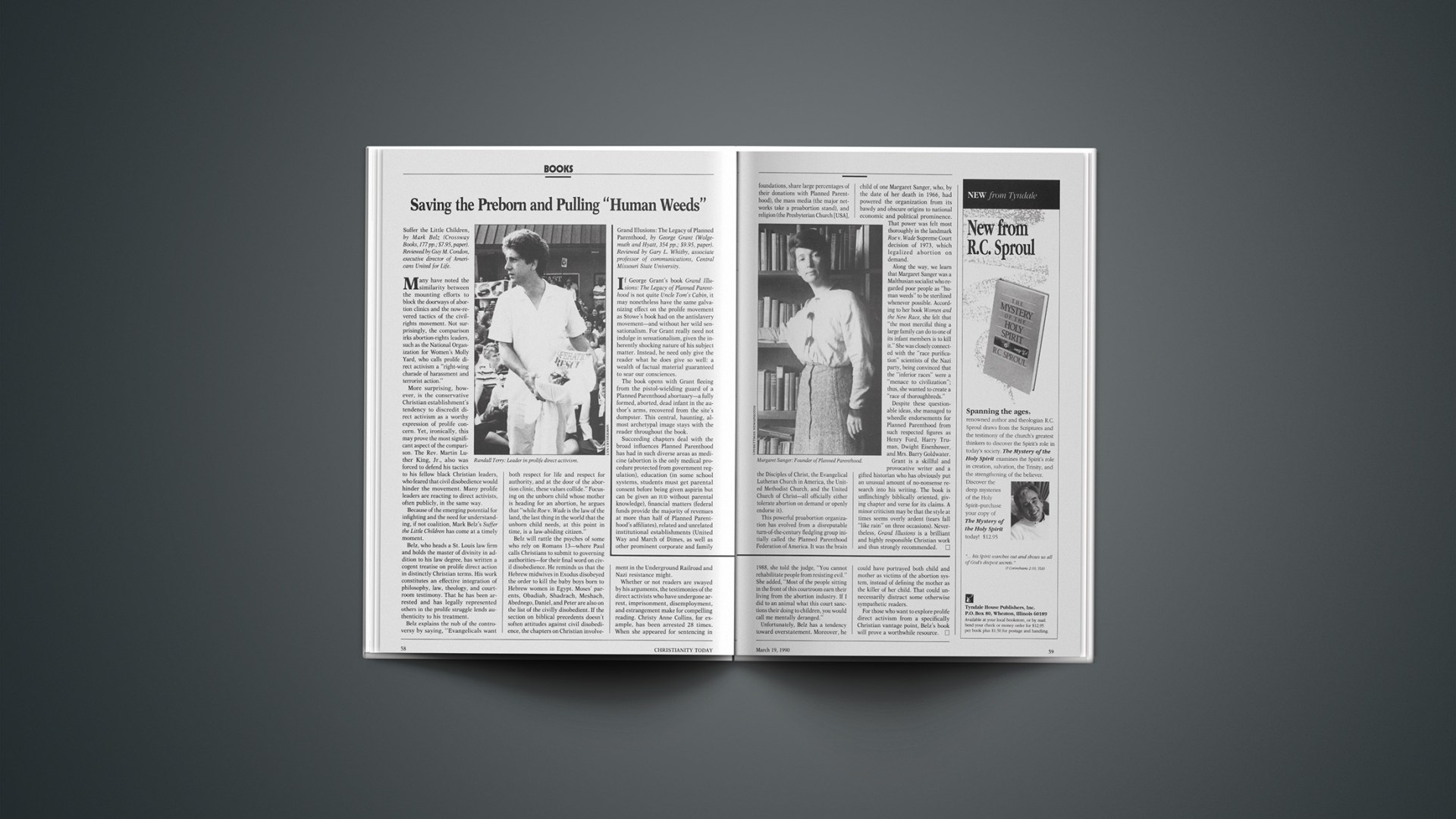

Grand Illusions: The Legacy of Planned Parenthood, by George Grant (Wolgemuth and Hyatt, 354 pp.; $9.95, paper). Reviewed by Gary L. Whitby, associate professor of communications, Central Missouri State University.

If George Grant’s book Grand Illusions: The Legacy of Planned Parenthood is not quite Uncle Tom’s Cabin, it may nonetheless have the same galvanizing effect on the prolife movement as Stowe’s book had on the antislavery movement—and without her wild sensationalism. For Grant really need not indulge in sensationalism, given the inherently shocking nature of his subject matter. Instead, he need only give the reader what he does give so well: a wealth of factual material guaranteed to sear our consciences.

The book opens with Grant fleeing from the pistol-wielding guard of a Planned Parenthood abortuary—a fully formed, aborted, dead infant in the author’s arms, recovered from the site’s dumpster. This central, haunting, almost archetypal image stays with the reader throughout the book.

Succeeding chapters deal with the broad influences Planned Parenthood has had in such diverse areas as medicine (abortion is the only medical procedure protected from government regulation), education (in some school systems, students must get parental consent before being given aspirin but can be given an IUD without parental knowledge), financial matters (federal funds provide the majority of revenues at more than half of Planned Parenthood’s affiliates), related and unrelated institutional establishments (United Way and March of Dimes, as well as other prominent corporate and family foundations, share large percentages of their donations with Planned Parenthood), the mass media (the major networks take a proabortion stand), and religion (the Presbyterian Church [USA], the Disciples of Christ, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the United Methodist Church, and the United Church of Christ—all officially either tolerate abortion on demand or openly endorse it).

This powerful proabortion organization has evolved from a disreputable turn-of-the-century fledgling group initially called the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. It was the brain child of one Margaret Sanger, who, by the date of her death in 1966, had powered the organization from its bawdy and obscure origins to national economic and political prominence. That power was felt most thoroughly in the landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision of 1973, which legalized abortion on demand.

Along the way, we learn that Margaret Sanger was a Malthusian socialist who regarded poor people as “human weeds” to be sterilized whenever possible. According to her book Women and the New Race, she felt that “the most merciful thing a large family can do to one of its infant members is to kill it.” She was closely connected with the “race purification” scientists of the Nazi party, being convinced that the “inferior races” were a “menace to civilization”; thus, she wanted to create a “race of thoroughbreds.” Despite these questionable ideas, she managed to wheedle endorsements for Planned Parenthood from such respected figures as Henry Ford, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, and Mrs. Barry Goldwater.

Grant is a skillful and provocative writer and a gifted historian who has obviously put an unusual amount of no-nonsense research into his writing. The book is unflinchingly biblically oriented, giving chapter and verse for its claims. A minor criticism may be that the style at times seems overly ardent (tears fall “like rain” on three occasions). Nevertheless, Grand Illusions is a brilliant and highly responsible Christian work and thus strongly recommended.

An Experiment In Unity

Torches Rekindled: The Bruderhof’s Struggle for Renewal, by Merrill Mow (Plough, 309 pp.; $10.50, paper). Reviewed by Arthur Boers, pastor of Windsor Mennonite Fellowship in Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

In the sixties and seventies, Christian intentional communities blossomed in North America, but many later faded or folded. Loosely affiliated with one such community, I witnessed the members’ bitter disillusionment. Two disenchanted families eventually made their way to a Bruderhof community.

The Bruderhof communities began as a renewal movement in Germany during the 1920s. Their founder, Eberhard Arnold, longed for a Christian community modeled on the early church and the Sermon on the Mount, committed to poverty, common property, modest dress, nonresistance, and separation from the world. Rejecting nazism, the group was persecuted and compelled to flee in 1938. Their communities ended up in England, Paraguay, and the United States. There are presently over a thousand Bruderhof members in five communities, mostly in the U.S.

Arnold led the Bruderhof communities into unity with the Hutterites, descendants of the sixteenth-century Anabaptist Reformation. Arnold died in 1935, and Torches Rekindled reflects on the history of the Bruderhof communities since then, a “struggle for renewal” marked by many conflicts.

Bruderhof communities have a reputation for joyful enthusiasm. Visitors return with stories of astonishing unity and dedication. But they are also uneasy. There is strong centralized leadership. Bruderhof members have unity of clothing. Women, in submissive modesty, wear long dresses and keep their heads covered. This separation from the world (and indeed from the wider church) both attracts and repels outsiders. Its foreignness is forbidding.

In their self-examination, scrutiny, and thoughtful confessions, Bruderhof members are not afraid to be self-critical. Sincerity shines through these pages. Yet the nature and personalities of the intense problems are often only hinted at, never adequately explained.

The book is actually transcripts of talks that Merrill Mow, a proselyte who eventually became a Bruderhof leader, gave to the community. Unfortunately, the editors did little to translate speech into text, thus retaining repetitions, awkward sentences, and confusing syntax. There is too much insider language and trivia. Yet their message deserves to be heard.

Bruderhof beliefs are simple, but nevertheless hard. “God is God, and we are not to make our own teachings.… We have no right to interpret God. What is important are the words of Jesus: first, sell what thou hast and give it to the poor; second, go and sin no more; third, love thy neighbor as thyself.… Do it. Don’t interpret it, don’t write papers about it, do it.”

Mow relinquished his prior theological achievements because private possessions—whether objects, knowledge, or skills—interfere with one’s relationship to God. Similarly, all members must give up their possessions. Likewise, newcomers cannot expect to practice their professions or skills; doing something well is too likely a source of pride. Calling for deep commitment, they discourage some from joining.

Torches Rekindled recounts the monumental efforts put forth to hold the Bruderhof communities together, even though scattered in North America, South America, and Europe. In the 1950s they were excluded (banned) from the Hutterites for usurping control of a Hutterite colony. The ban lasted for 20 years. Overcoming those hostilities was no mean feat, largely the work of Heini Arnold, Eberhard’s son.

The energy devoted to unity is astonishing, involving frequent exchanges and special meetings. Expecting a high degree of unanimity and obedience, the communities laboriously work through many issues. We witness lengthy and emotional meetings. Conflicts inevitably end with the mournful repentance (or departure) of dissidents.

This seems exceedingly introspective and draining, but they insist that unity is mission: “that they may all be one … so that the world may believe that thou hast sent me” (John 17:21).

I was moved by their desire to be rooted in God. Deeply mystical, they see God working in all of life. Since they believe that God is known in community, they are especially wary of such community destroyers as individualism, gossip, quarreling, opinionatedness, and disunity.

The Bruderhof communities take seriously their outreach in deed and word. And, against the odds, they grow. Relying on God and demanding a wholehearted commitment to the gospel, they do not worry about scaring people away. The challenge may be unpopular, but I hear the gospel in it. “Every one of us has to decide whether he is on the side of Jesus … or whether he is on the side of power, efficiency, gifts, or anything else that misleads us”

A Battalion Of Peacemakers

Non-Violence: The Invincible Weapon? by Ronald J. Sider (Word, 118 pp.; $6.99, paper). Reviewed by Rodney Clapp, general books editor for InterVarsity Press.

It remains, to most of us, an unlikely premise: rather than building armies of soldiers, build armies of peacemakers; rather than arming them with rifles, arm them with convictions; rather than preparing them to kill, prepare them to die. In his newest book, Ron Sider is not concerned to make every Christian a pacifist, assuming instead that all Christians are followers of the Prince of Peace. “To have any integrity, both the pacifist and just war traditions demand a massive commitment to nonviolence.” Thus, violence should always be a last resort. “How then can Christians in the just war tradition claim they are justified in resorting to war until they have devoted vast amounts of time and money to explore the possibilities of non-violence?”

Accordingly, this small and simple book is an appeal to the imagination. The first three-fourths of it is devoted to accounts of successful nonviolent resistance: in ancient Palestine, Gandhi’s India, the Norway and Bulgaria of World War II, and in Central America. Sider gives an entire chapter to the bloodless 1986 overthrow of Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

Sider’s tales have a cumulative effect. It is easy enough to dismiss nonviolence as a sustained political strategy when we limit ourselves to one or two examples of successfully employed nonviolence. So the most famous example (Gandhi) is dismissed by an appeal to “real” causes, such as the civility of the British, and any serious consideration of nonviolence is avoided. But what happens when the catalog of examples is lengthened? As nonviolence succeeds in various times and places, how much longer can we insist that it is idle dreaming?

Sider is never utopian. He grounds the Christian concern for peace in witness to Christ, allowing that nonviolence will not always be effective. In some ways, he is only asking us to see the real and the obvious in a new light—the light of the Cross.