The architect of the Great Books, Mortimer Adler, has moved beyond big ideas to the mysteries of faith.

You would not usually expect a renowned, twentieth-century philosopher to be a friend of orthodox Christianity. Yet one keeps running into people—committed Christians, deep thinkers all—who have nothing but respect for Mortimer Adler, the author, teacher, philosopher, and intellectual giant who is best known, perhaps, for his work with the Great Books series of the classics of Western culture. They listen to his lectures (on education and philosophy, mostly), they read his books (over 25 to date), and they generally give the impression they would give their eye teeth to speak with the man. Apparently there are some things about his work that attract the righteous.

But Mortimer Adler’s entry in Who’s Who in America gives little hint that he is a believer. A philosopher educated at that hotbed of naturalism, Columbia University, and a longtime professor at the University of Chicago—no, there is no clue there.

How about his résumé? He left the university in 1942 to start the Institute for Philosophical Research in Chicago, a position that enabled him to give editorial direction to the fifteenth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and develop, edit, write, promote (you name it) the Great Books of the Western World, on the surface a collection of classics, but in reality an attempt to revolutionize American education. No. These are signs of extraordinary energy and scholarship, perhaps, but certainly not Christian apologetics.

Adler’s office and headquarters on Ontario Street, a half-block off Michigan Avenue’s “Magnificent Mile” on Chicago’s Near North side, has the unmistakable feel of a college philosophy department. Old books on philosophers and logic line the walls. Not far away are shelf after shelf of new books: several sets of the Great Books, and whole rows of multiple copies of Adler-authored books—heady titles like Reforming Education, Six Great Ideas, Ten Philosophical Mistakes, The Paideia Proposal. There are dust jackets for his newest books, including his most recent, Truth in Religion: The Plurality of Religions and the Unity of Truth. There are also celebrity photographs (Adler with TV commentator Bill Moyers, another with Pope Paul VI), and awards, medals, and certificates of appreciation.

“I’ve known I would be a philosopher ever since one of my professors at Columbia, F. J. E. Woodbridge, gave me a copy of Aristotle’s Metaphysics in 1931,” says Adler. “I read it, and was hooked.”

Behind his desk is a 15-foot-long credenza with hundreds of open files, future books in progress: “I’ve talked my publisher [Macmillan] into letting me do two books a year from now on. I’m 88 and I still have much to do.”

Adler has never been known to be shy about saying things. Friends might call him loquacious; opponents might say cantankerous. He himself would probably settle for disputatious. He believes in rational argumentation in its best, logical sense.

It is when Mortimer Adler talks about the debates and the controversies and the battles he has spent his life fighting that his voice rises above octogenarian tiredness, and we get clues to the fundamentals of his thought.

On scientists: “Scientists have exceeded their bounds. They are theologically naïve. But that doesn’t seem to stop them from talking about beginnings and endings. The beginning wasn’t a Big Bang and the end won’t be a Final Freeze. But don’t try telling a scientist that.

“The Hubble telescope isn’t going to tell us anything new about the metaphysical world, but that doesn’t stop Stephen Hawking from pretending [in A Brief History of Time] that he can. Scientists barge in where angels fear to tread.”

On the language philosophers (the school of linguistic philosophy developed by Ludwig Wittgenstein earlier this century and dominant in the universities): “Minor annoyances. I love metaphysics. But the language philosophers want to be scientists, not metaphysicians.”

On the mood of the country: “Anti-intellectual.”

On academics: “Hopeless.”

For all his life, Adler has written, taught, and lectured on a central, classical truth: There is one, absolute unity of truth, and the philosopher’s job is to discover and define it so the good life can be known to all. Now, when Adler sees scientists, scholars, and even the man-on-the-street claim that truth is merely relative, that all individuals shop for it themselves and create their own recipe, with a pinch of culture, a dash of ethnicity, and a smidgen of serendipity, Adler sees red.

Perhaps it is just this foundational presupposition—the conviction that a single truth exists—that has attracted orthodox Christians to him.

Yet, in his years of swashbuckling swagger through Columbia, Chicago, educational reform, and popular philosophical publishing, Adler has never aligned himself with, fought for, or even talked like he belonged to, Christianity.

Where does he stand, then, on the Christian faith?

It is Sunday morning at Grace Episcopal Church, just a block from historic Dearborn Station on Chicago’s Near South side. This three-by-four-block area knew the bustle and joy of creative enterprise early in this century when Printers’ Row, Chicago’s prestigious publishing empire, flourished. When the big printing plants went south, however, the area fell to semislum status. Now it is being reborn under yuppie influence.

It is still a balkanized neighborhood—a half-block walk in any direction can take you from the land of gourmet-food stores and hair salons to low-income housing, and another half-block has you back to $300,000 condos and upscale bookstores.

Grace Church ministers to the patrons of all these communities, and on this morning, Mortimer Adler is guest preacher.

“Six years ago they asked me to preach, and I said yes,” he explains. Once a year, every year, he ministers to this mixed-race, mixed-class, mixed-everything congregation of about 40.

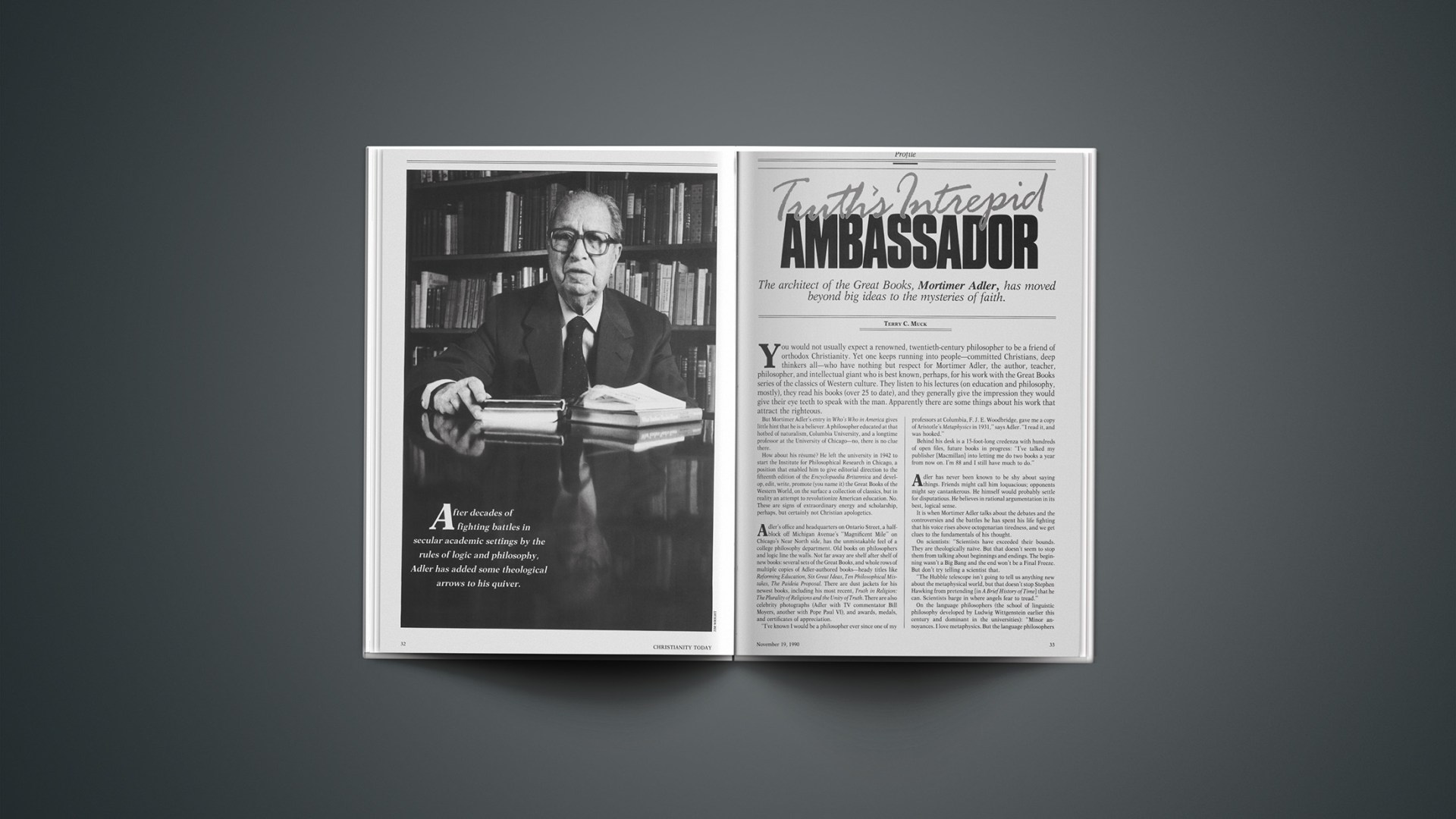

Adler looks less imposing in church than he does in his office. At the office, he is a lion in his den, bellowing midwinterview to his administrative assistant of 28 years, Marlys Allen, to bring him a copy of the Syntopicon, the introductory volume he wrote to the Great Books, distilling the 102 key ideas of Western intellectual history. In his office he sits large behind his desk, master of his domain.

In church, by contrast, he walks to the podium with a tentative, 88-year-old shuffle, he looks his 5′2″ height, and he selectively participates in the Anglican liturgy, not willing to attempt even the slow cadence of the hymns.

The minute Adler finally gets to the pulpit and begins a 30-minute homily, the disparity between office and church disappears altogether.

The sermon is remarkable. How many sermons have you heard recently that began with a quote from the second-century Latin apologist Tertullian? Adler’s does.

“I believe because it is absurd,” Adler quotes and quickly shows how Augustine and Aquinas both second Tertullian’s credo.

Adler then himself ascribes to the credo: “Articles of faith are beyond proof. But they are not beyond disproof. We have a logical, consistent faith. In fact, I believe Christianity is the only logical, consistent faith in the world. But there are elements to it that can only be described as mystery.”

We read the Nicene Creed together, and Adler glosses on the three main mysteries of the Christian tradition: the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Resurrection.

“Your faith and my faith must include these three mysteries. They are difficult to understand. They are not unintelligible—God understands them. But for us there is an element of mystery.

“I’m not always sure whether I’m making that judgment as a philosopher or a Christian believer.”

But Adler’s credo concludes: “The greatest error anyone can make is to think they can fully understand these three mysteries. It makes a mockery of faith.”

After decades of fighting battles in secular academic settings by the rules of logic and philosophy, Adler has added some theological arrows to his quiver.

One is the sovereignty of God: “In the beginning, the scientists forgot about God. Now when they realize he must be there, they’re trying to remake him in their own image.”

Another is the truth of Christianity: “A property of true religion is to be evangelical. When I hear the term evangelical, I don’t think about TV preachers—I think about the mission. Christianity is the only world religion that is evangelical in the sense of sharing good news with others. Islam converts by force; Buddhism, without the benefit of a theology; Hinduism doesn’t even try.”

With these additional insights, Mortimer Adler faces the future with hope: “I’m pessimistic about the future in the short run. We won’t get over relativism in 10 or even 20 years. But in the long run, by the middle of next century, I’m convinced we can get philosophy and education back on track.”

One suspects that such a prospect will be helped along by Adler’s persuasive efforts.

Mortimer Adler usually makes it clear to interviewers—either explicitly or indirectly—that he will not talk about his own faith. In so doing, he probably shows more sense than most celebrity Christians. He refuses to wear his faith like a badge.

But one wonders if this restriction is really necessary. These days, so many of his books, conversations, and lectures invariably lead to absolute truth and God. The mystery of why Mortimer Adler is into the mystery of Christian theology is really no mystery at all. In 1984 he became a Christian.

“My chief reason for choosing Christianity was because the mysteries were incomprehensible. What’s the point of revelation if we could figure it out ourselves? If it were wholly comprehensible then it would be just another philosophy.”

Call him a Christian, then.

But if you should get carried away and ask this wonderful old man to tell you the story of his conversion, he may arise, and mumbling something about another appointment, pick up and leave. He is still a professional philosopher, and has work to do—and arguments to win.