Croatia’s evangelical church has been thrust into a breadth of service far out of proportion to its size.

You can’t huddle for days in a cellar with your neighbors, mortar shells bursting about you, and maintain a self-imposed isolation. Croatian writer and editor Ksenja Magda says the shared experience of a brutal war has forced the evangelical church in that former Yugoslavian republic out of its shell and into the streets, the homes, and even the hearts of its neighbors.

Croatia’s evangelical church is one of Europe’s smallest evangelical bodies, counting only 3,000 members in a predominantly Roman Catholic country of 4.5 million. But it has been thrust into a breadth of service far out of proportion to its size.

Six or seven Protestant relief organizations and individual churches in Croatia administer multimillion-dollar relief projects financed largely by Western churches and Christian relief organizations. Nearly every local church has been pressed into service to its own community or communities around it, as some 600,000 refugees from Croatia and neighboring Bosnia-Herzegovina flee the vicious ethnic fighting that has engulfed the region. It is a role for which the churches were unprepared, in a war that has pitted Orthodox Serbians against Catholic Croats, and resulted in the deliberate destruction of both Orthodox and Catholic churches.

In Marshal Tito’s nonaligned Yugoslavia, Christians enjoyed more freedom than in communist countries within the Soviet sphere. However, until a few years ago, a theology of withdrawal from the world coupled with what some Christian leaders there describe as a “sectarian spirit” shielded the evangelical church from contact with nonevangelical outsiders and kept it splitting into ever-smaller groups. At less than one-tenth of 1 percent of the total population of the former Yugoslavia, the Protestant church had hardly grown in decades.

That is changing, as a shocked church confronts staggering human need. In Croatia, where nearly 3,000 apartments and houses have been damaged or destroyed since fighting began last year, all available housing is full to overflowing. For the first nine months of the war it was possible to house most refugees with families or in hotels. Now, as the conflict in Bosnia broadens and some 1.8 million Bosnians surge toward borders in a desperate attempt to escape the “ethnic cleansing” campaign of Serbian forces, tent cities have sprung up. Refugee trains stranded at inhospitable borders turn into cramped “hotels” for thousands of miserable, hungry, thirsty, and frightened people.

In Croatian cities like Osijek, where bombing has destroyed 50 to 90 percent of the local industries, thousands of people are unemployed and unlikely to find work in the near future. The Croatian economy hovers on the edge of disaster as inflation surges. The value of the average I Croat’s salary has dropped from about $350 a month to $60, barely enough to pay the soaring cost of utilities—not to mention food, housing, and clothing.

Relief Efforts

One of the largest of the new evangelical humanitarian agencies in Croatia is Duhovna Stvarnost, an interdenominational organization that began many years ago as a Christian publishing house but whose work now is 80 percent humanitarian. The organization provides food and basic supplies for some 500 refugee families in Zagreb and 600 local people whose income is too low to supply their basic needs. In addition, it operates a clothing distribution center and, through Western relief organizations, provides medicines and equipment to hospitals.

My Neighbor, the humanitarian outreach of the Baptist Union of Croatia, operates relief centers in eight communities through the auspices of local Baptist churches. The churches directly administer relief programs or, when larger shipments of goods are received, oversee their distribution through government agencies.

Agape, the humanitarian organization of Croatia’s Pentecostal denominations, administers relief through 12 regional centers, where church leaders have overseen the distribution of nearly $2 million worth of food, clothing, toiletries, and medicine.

Gethsemane, an independent evangelical mission that grew out of the 30-member Baptist church in Sisak, now distributes aid to some 1,000 families.

A number of Western evangelical organizations and churches have channeled tons of supplies through the Croatian agencies. Food, blankets, medicine, and clothing have come from the Tear Fund, the relief arm of Britain’s Evangelical Alliance; Samaritan’s Purse, which sent a 72-bed emergency field hospital to be set up on the edge of the war zone; Euroevangelism Trust; World Vision; Operation Blessing; the Assemblies of God; and dozens of local churches and groups in Europe. Other organizations such as the World Council of Churches, World Relief, and the European Baptist Federation have also helped fund the efforts.

Spiritual Aid

Churches offer not only humanitarian but spiritual help. Some 60,000 copies of Billy Graham’s Peace with God, published by Duhovna Stvarnost, have been handed out to refugees, soldiers, and others. Many more could be distributed if funds were available for printing, says Duhovna Stvarnost chairman Branko Lovrec, who translated the book.

Some 400,000 copies of the Gospel of Mark have been printed by Iavorie, the publishing house of the Evangelical Church of Croatia, the country’s largest Pentecostal denomination. So far, about 100,000 Gospels and tracts have been distributed to refugees, says Damir Spoljaric, assistant director of the Evangelical Theological Faculty and temporary head of the publishing division.

Students Plan Return To War-Damaged Seminary In Croatia

When bombardment of Osijek, Croatia, forced a flood of refugees out of the city last fall, a seminary was among those that found temporary refuge outside the country. Leaving behind a new, million-dollar building and hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of books and equipment, some 60 students of the Evangelical Theological Faculty and their instructors moved to a makeshift campus in the facilities of churches in two towns in neighboring Slovenia, once a republic of Yugoslavia, now an independent country.

While classes continued in Slovenia, the sturdy new building in Osijek served a new and unanticipated function—its basement transformed into a neighborhood bomb shelter and temporary living quarters for people forced underground for weeks at a time.

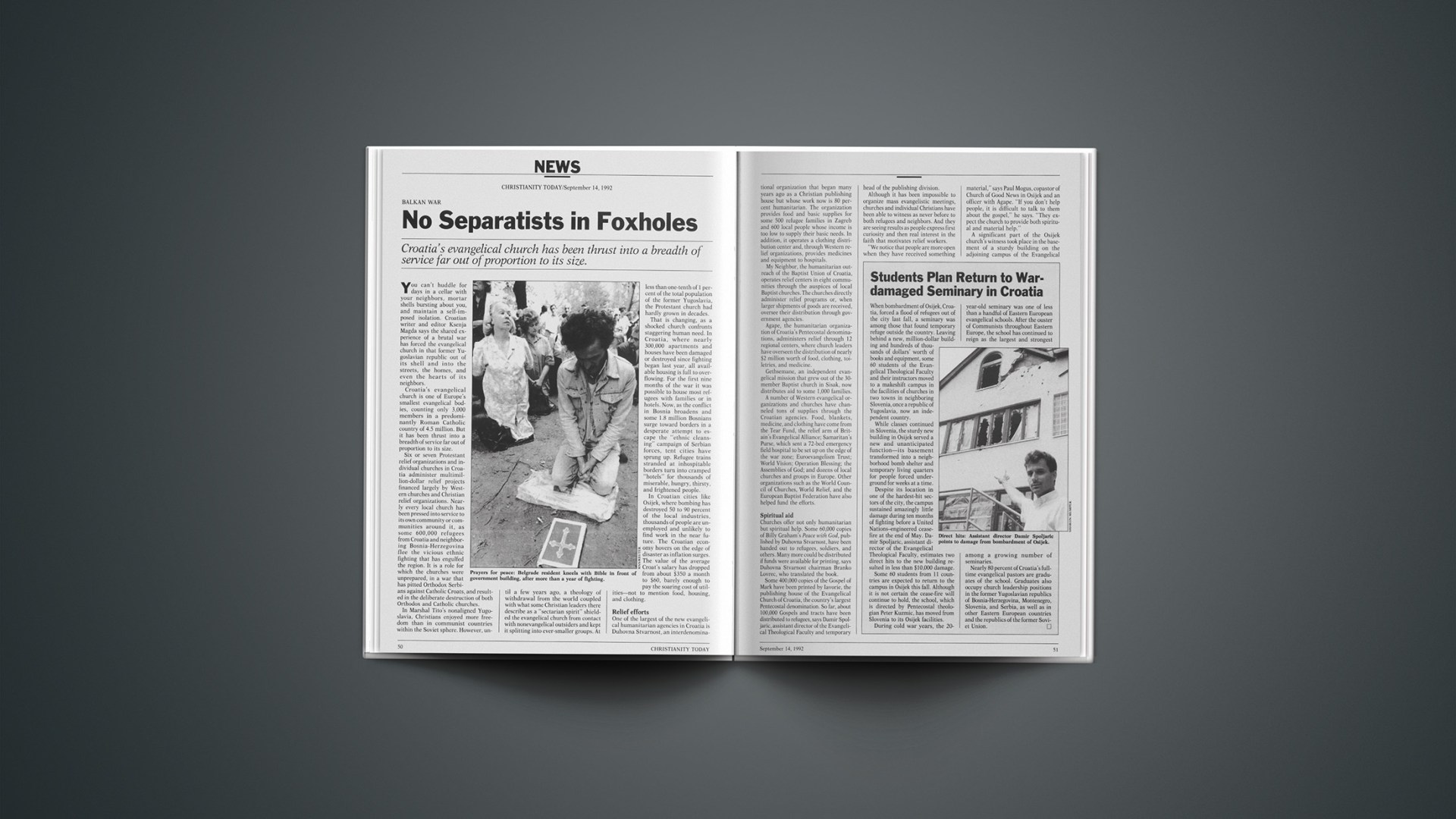

Despite its location in one of the hardest-hit sectors of the city, the campus sustained amazingly little damage during ten months of fighting before a United Nations-engineered cease-fire at the end of May. Damir Spoljaric, assistant director of the Evangelical Theological Faculty, estimates two direct hits to the new building resulted in less than $10,000 damage.

Some 60 students from 11 countries are expected to return to the campus in Osijek this fall. Although it is not certain the cease-fire will continue to hold, the school, which is directed by Pentecostal theologian Peter Kuzmic, has moved from Slovenia to its Osijek facilities.

During cold war years, the 20-year-old seminary was one of less than a handful of Eastern European evangelical schools. After the ouster of Communists throughout Eastern Europe, the school has continued to reign as the largest and strongest among a growing number of seminaries.

Nearly 80 percent of Croatia’s full-time evangelical pastors are graduates of the school. Graduates also occupy church leadership positions in the former Yugoslavian republics of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro, Slovenia, and Serbia, as well as in other Eastern European countries and the republics of the former Soviet Union.

Although it has been impossible to organize mass evangelistic meetings, churches and individual Christians have been able to witness as never before to both refugees and neighbors. And they are seeing results as people express first curiosity and then real interest in the faith that motivates relief workers.

“We notice that people are more open when they have received something material,” says Paul Mogus, copastor of Church of Good News in Osijek and an officer with Agape. “If you don’t help people, it is difficult to talk to them about the gospel,” he says. “They expect the church to provide both spiritual and material help.”

A significant part of the Osijek church’s witness took place in the basement of a sturdy building on the adjoining campus of the Evangelical Theological Faculty during months of frequent bombardment by Serbian forces (see “Students Plan Return to War-damaged Seminary”). During attacks, nonevangelical neighbors shared makeshift quarters underground, gladly joining in nightly worship and prayer meetings. A number of those people became Christians and were baptized this summer. Others continue to come to the church, which, despite the fact that some members are still scattered in other countries, is as full as it has ever been on Sunday mornings.

Even Bosnian Muslims have been open to the gospel. “Cross-cultural sharing is going on with Muslims,” says Kesnija Magda. “They very much depend on what we as Christians give them.” In Cakovic, at the Hungarian border, Croatian evangelical churches have been providing relief goods to Muslim Bosnians stranded on trains and, at their request, bringing them to church services.

Nationalistic Spirit

It is difficult to say whether evangelical churches are growing, church leaders say. Many church members are scattered throughout Croatia or other countries. Some churches are in Serbian-held areas, and leaders are unable to get information about them. Church leaders can say, however, that people are being converted.

In a country so strongly Roman Catholic, where church membership is tied up with nationalistic spirit, conversion is difficult. Those most responsive to evangelistic efforts are former Communists or other unchurched people, says Spoljaric. Nevertheless, he says, the fact that the evangelical church is ethnically mixed appeals to many people who are disgusted with the war.

The crisis has forever changed not only the former Yugoslavia and its citizens, but the evangelical church in Croatia. Never again will it be able to fit back into its shell. And despite the tragedy that has befallen their country, Croatian Christians have hope for the future.

“Croatia—and Yugoslavia as a whole—has never had a spiritual awakening,” says Magda. “Many people are hoping and praying that after this war, people will come to know the Lord in a special way. We hope it is the same for Serbia and the other parts of the former Yugoslavia.”

By Sharon E. Mumper in Croatia.