Illegal immigration tests the compassion and reason of Christians confronting this emerging national crisis.

A recent bout of raids on “illegal immigrants” had one Hispanic pastor’s church members frustrated and worried. As the Latino believers—some in the United States illegally, most legally, yet all in search of a better life—gathered for a service, their pastor spoke reassuringly: “Esta no es oficina de imigracion. Es casa de Dios y puerta del cielo!” he said, paraphrasing the words of the biblical refugee Jacob. (“This is not the office of immigration. It is the house of God and the door of heaven!”)

Indeed, thousands of Mexican believers in recent years have illegally crossed the border into California, joining millions of others in search of work, good health care, and education for their children.

Whether they are called illegals or undocumented workers, the rising U.S. immigrant population, and especially the growing presence of Latinos in the Southwest, has set a political brushfire that is testing the core of constitutional guarantees.

For evangelical Christians, the immigration issue raises many scriptural questions, such as how to apply the biblical mandate to care for the poor and dispossessed; how to resolve the tension between nationalism and the global concerns of Christianity; and whether evangelical theology can address the real-life problem of developing a compassionate and orderly immigration policy.

With the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement by Congress, the fundamental relationship between Mexico and the United States is shifting dramatically on all fronts. And at times, the goals of public policy and Christian ministry are in conflict.

“I would say that the evangelical church doesn’t even perceive the problems,” says Luis Madrigal, a former World Vision worker who is now executive director of the new Hispanic Association for Bilingual/Bicultural Ministries (HABBM) in Los Angeles.

While some evangelicals and churches have helped individual families or groups of immigrants, Hispanic Christian leaders say few evangelical leaders have outspokenly opposed the politically popular trend of blaming undocumented workers for California’s economic and state budgetary woes.

“Given the rhetoric going on in California … the evangelical church needs to come forward and question [its] attitude,” says Eldin Villafane, professor of Christian social ethics at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and author of The Liberating Spirit: Towards an Hispanic-American Pentecostal Social Ethic (Eerdmans).

The new immigrants

Illegal immigrants exist in America’s shadows, hoping to avoid the authorities, while scrambling to make a living on the lowest rung of the economic ladder.

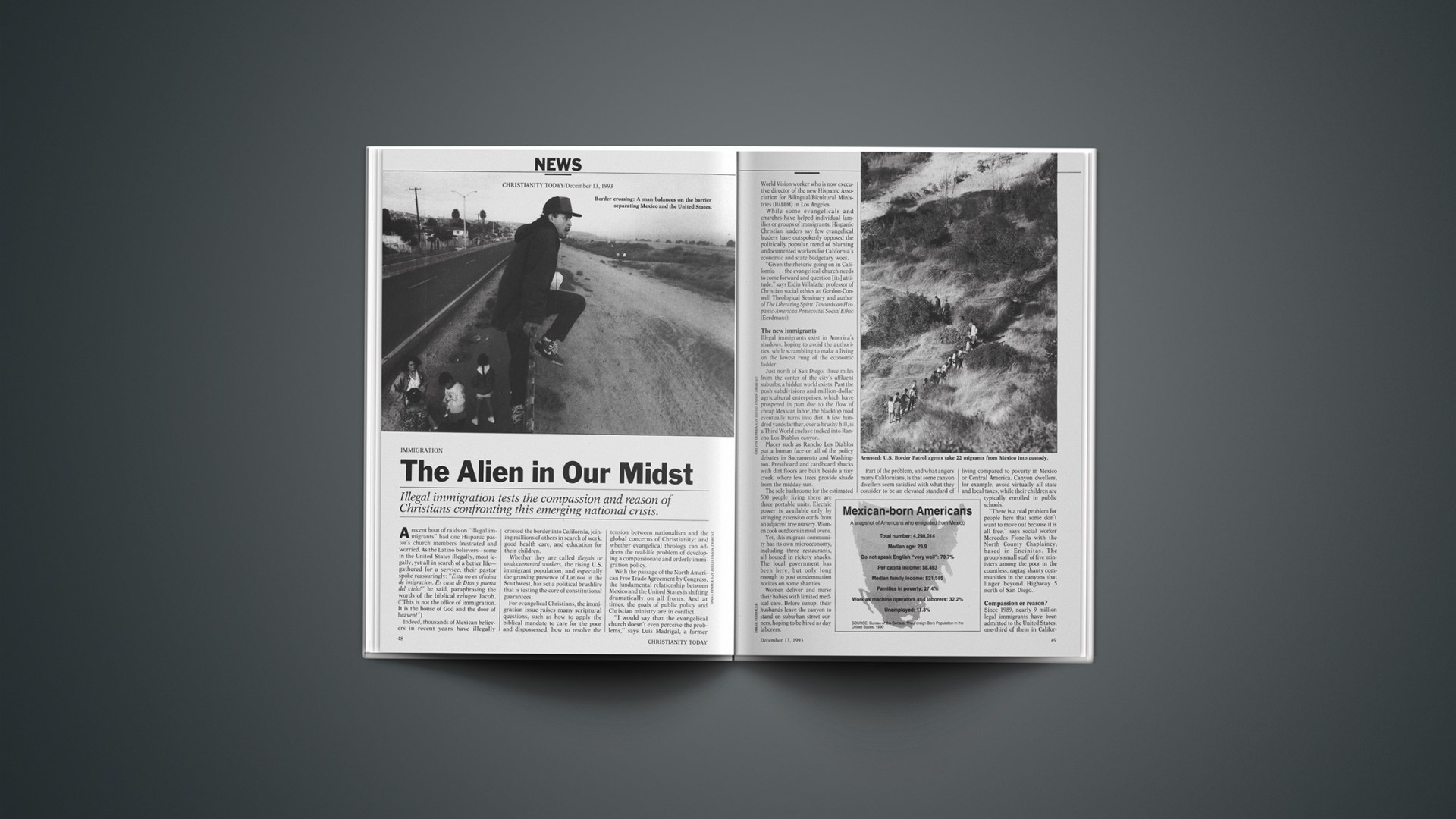

Just north of San Diego, three miles from the center of the city’s affluent suburbs, a hidden world exists. Past the posh subdivisions and million-dollar agricultural enterprises, which have prospered in part due to the flow of cheap Mexican labor, the blacktop road eventually turns into dirt. A few hundred yards farther, over a brushy hill, is a Third World enclave tucked into Rancho Los Diablos canyon.

Places such as Rancho Los Diablos put a human face on all of the policy debates in Sacramento and Washington. Pressboard and cardboard shacks with dirt floors are built beside a tiny creek, where few trees provide shade from the midday sun.

The sole bathrooms for the estimated 500 people living there are three portable units. Electric power is available only by stringing extension cords from an adjacent tree nursery. Women cook outdoors in mud ovens.

Yet, this migrant community has its own microeconomy, including three restaurants, all housed in rickety shacks. The local government has been here, but only long enough to post condemnation notices on some shanties.

Women deliver and nurse their babies with limited medical care. Before sunup, their husbands leave the canyon to stand on suburban street corners, hoping to be hired as day laborers.

Part of the problem, and what angers many Californians, is that some canyon dwellers seem satisfied with what they consider to be an elevated standard of living compared to poverty in Mexico or Central America. Canyon dwellers, for example, avoid virtually all state and local taxes, while their children are typically enrolled in public schools.

“There is a real problem for people here that some don’t want to move out because it is all free,” says social worker Mercedes Fiorella with the North County Chaplaincy, based in Encinitas. The group’s small staff of five ministers among the poor in the countless, ragtag shanty communities in the canyons that linger beyond Highway 5 north of San Diego.

Compassion or reason?

Since 1989, nearly 9 million legal immigrants have been admitted to the United States, one-third of them in California alone. But California is also home to more than half of the nation’s 4 million undocumented immigrants.

Perhaps as many as three-quarters of those who are undocumented and living in California are Mexicans who have crossed the border near Tijuana.

Add to that 3 million “illegals” who claimed amnesty in California under a 1986 federal law that granted citizenship to any illegal alien who had U.S. residency before 1982. The result has been a radical change in California’s ethnic landscape. San Diego has gained the nickname “the illegal immigrant capital of the world,” due largely to its 30-minute proximity to the border and Tijuana.

On the edge of Tijuana, a city of 1 million people, is a massive, urine-scented, concrete-lined river of green slime and a foreboding, steel-fence border. Despite the fence and concrete barrier, the border is anything but secure. Most of the illegal immigration occurs along a 200-mile strip in California and Texas that is patrolled by only 200 border police.

President Clinton, seeking to respond to pressure from Californians, has proposed adding 600 new border-patrol officers.

In addition, California governor Pete Wilson, facing the gubernatorial election in 1994 and low popularity due to the state’s poor economy, has offered several controversial initiatives:

• A constitutional amendment to deny citizenship to children born in the United States to undocumented immigrant parents.

• “Congressional action to remove rewards for illegal immigration by repealing the federal mandates that make illegal immigrants eligible for health [care], education, and other benefits.”

• “Creation of a tamper-proof, legal resident eligibility card that would be required as proof of eligibility for all legal residents seeking benefits.”

A recent Los Angeles Times survey proves the popularity of Wilson’s proposals, with 76 percent of those polled agreeing that illegal immigrants “take more from the national economy in social services and health care than they contribute in productivity and taxes.”

Explaining his point of view on illegal immigration, Wilson has commented, “We can no longer allow compassion to overrule reason.”

This struggle between compassion and reason places the policy debate clearly into moral and religious categories. HABBm’s Madrigal believes many of California’s evangelicals are either ambivalent about the immigration issue or assert strongly that much more stringent border controls are needed.

Opinions of Californians in part can be traced to the realization that the state’s population has shifted dramatically. Today, whole sections of major cities once populated by Anglos or Blacks now have a strong Hispanic presence. Educating the children of illegals now costs the state about $5.3 billion a year. About $350 million a year is spent incarcerating illegals, who make up about 14 percent of the state’s prison population.

Many Californians believe Mexicans are content to remain culturally distinctive while in the United States rather than assimilating into mainstream society.

Raul Ries, pastor of a multiethnic church in Diamond Bar, California, believes that many Hispanics, as well as other foreigners, are entering the United States because they are seeking economic, educational, or social opportunities. Ries says many of the immigrants are unskilled, uneducated, and take jobs at low wages. “We are seeing our country become a foreign land,” he says. “Every ethnic and minority group in America is demanding special rights and privileges. The result is a dividing of America.”

Patriotism and faith

The 2,000-member Solana Beach Presbyterian Church (PCUSA), a largely Anglo evangelical church in the San Diego area, is directly involved in working with immigrants. The church sends doctors into the canyons, teaches English classes, and works alongside the North County Chaplaincy.

Donald McCullough, Solana senior pastor, says, “We have been slow in thinking through how Christians should respond and what guidance we should be offering. There is very little movement that I can discern for the rights of Hispanics and aliens. In general, there is bewilderment.”

McCullough says Christians should “speak the truth about what the Bible calls us to do for the alien in our midst.” He believes relationship-building is a good first step.

Concerned that few evangelicals have taken a position in the immigration debate, Madrigal and other leaders have considered petitioning Evangelicals for Social Action (ESA) to help give a greater voice to their concerns.

Ron Sider, ESA executive director, told CHRISTIANITY TODAY, “As long as there is an enormous gulf between affluent North Americans and a poor Mexico and Central America, a lot of people will want to try to come to this country.” Sider says an effective and compassionate response is taking measures to help lift the economies of other countries. While he supports the North American Free Trade Agreement, he also believes more could be done by Christian groups.

In the meantime, Sider says the California controversy challenges Christians to debate whether modern-day nation-states with tight border control are in conflict with biblical teaching.

Evangelicals, Sider says, must view the controversy in light of the biblical standard that “everyone is a creation of God and is my brother or sister.”

Among Roman Catholics, immigration issues have provoked sharp comment as well. Cardinal Roger Mahoney has said, “The right to move across the borders to escape political persecution or in search of economic survival [is] a theme of extraordinary importance in Catholic social thinking. We must not follow the lead of those fanning the flames of intolerance.”

Whether Protestant or Roman Catholic, the immigrant church in the United States perhaps has the most difficult balancing act. Recently, in one California neighborhood, a surprise workplace raid by immigration agents netted a Latino Apostolic congregation’s youth auxiliary president and a companion, according to an account by Daniel Ramírez, a Pentecostal Christian who is an academic administrator at Stanford University.

Hours later, church members “dispatched [a car] to the U.S.—Mexican border. Discreet phone signals were arranged. Contact was made with the young men in Tijuana. Prayers were offered on their behalf.” Ultimately, the “lost sheep” were “restored … to the congregation in time for the Sunday night evangelistic service, much to the brethren’s joy.”

The local church that conducted the operation is affiliated with the Apostolic Assembly Churches of the United States, a Hispanic Pentecostal denomination of about 50,000, which also has many members in Mexico.

Ramírez says it is nearly impossible for the White evangelical church to comprehend the despair of Latino immigrants because of the socio-economic gulf between church communities that may reside in the same area.

Gordon-Conwell’s Villafan̄e says, “The bottom line for Christians is still the scriptural warranties rather than the constitutional warranties.” He says, “The tendency of the evangelical is not to address social issues until they become legitimized by leaders.” If evangelicals don’t get involved, he notes, this could result in another blemish on the church’s social witness much like when conservative Christians avoided early involvement in the civil-rights movement.

As the ethnic makup of the United States changes, the church’s unmet challenge is to bring biblical principles into the immigration policy debate.

By Joe Maxwell in San Diego.