When the Christian Coalition held its first rally in Orlando in 1989, the organization boasted 5,000 members and the rally drew 600 supporters. Today, little more than six years after its inception, the coalition numbers 1.6 million members and supporters, includes 2,000 local chapters, and distributes 33 million voter guides. In his book Active Faith, founder Ralph Reed writes that the Christian Coalition is a "middle class, highly educated suburban phenomenon of baby-boomers with children who are motivated by their concerns about family" and has "normalized a religious impulse that has heretofore been treated as abnormal."

But others in the Christian community might interject: That depends upon what you mean by "normalize" and "impulse." Tony Campolo, professor of sociology at Eastern College (St. Davids, Penn.), has said that "the people who make up this group represent only a minority of the Christian community." To counter the perception that the coalition is the sole voice for the believing community in the political arena, Campolo, along with other colleagues who do not identify themselves as part of the Religious Right, launched in late 1995 an organization known as the Call for Renewal. The Call mounted its campaign both to dissent publicly from the coalition's policies and perceived allegiances and to develop "a new way" for Christians to engage in politics.

Despite both of these activist impulses, Charles Colson, one-time political insider and leading Christian voice on things cultural and political, expresses concern that the day may be fast approaching when Christians, Left or Right, might not have a voice in the political conversation at all. He wrote in ct last April 29: "Christians joining the abortion debate are denounced as 'illegitimate political participants … in the sense of operating outside the rules of the political system.' Christians are becoming outcasts."

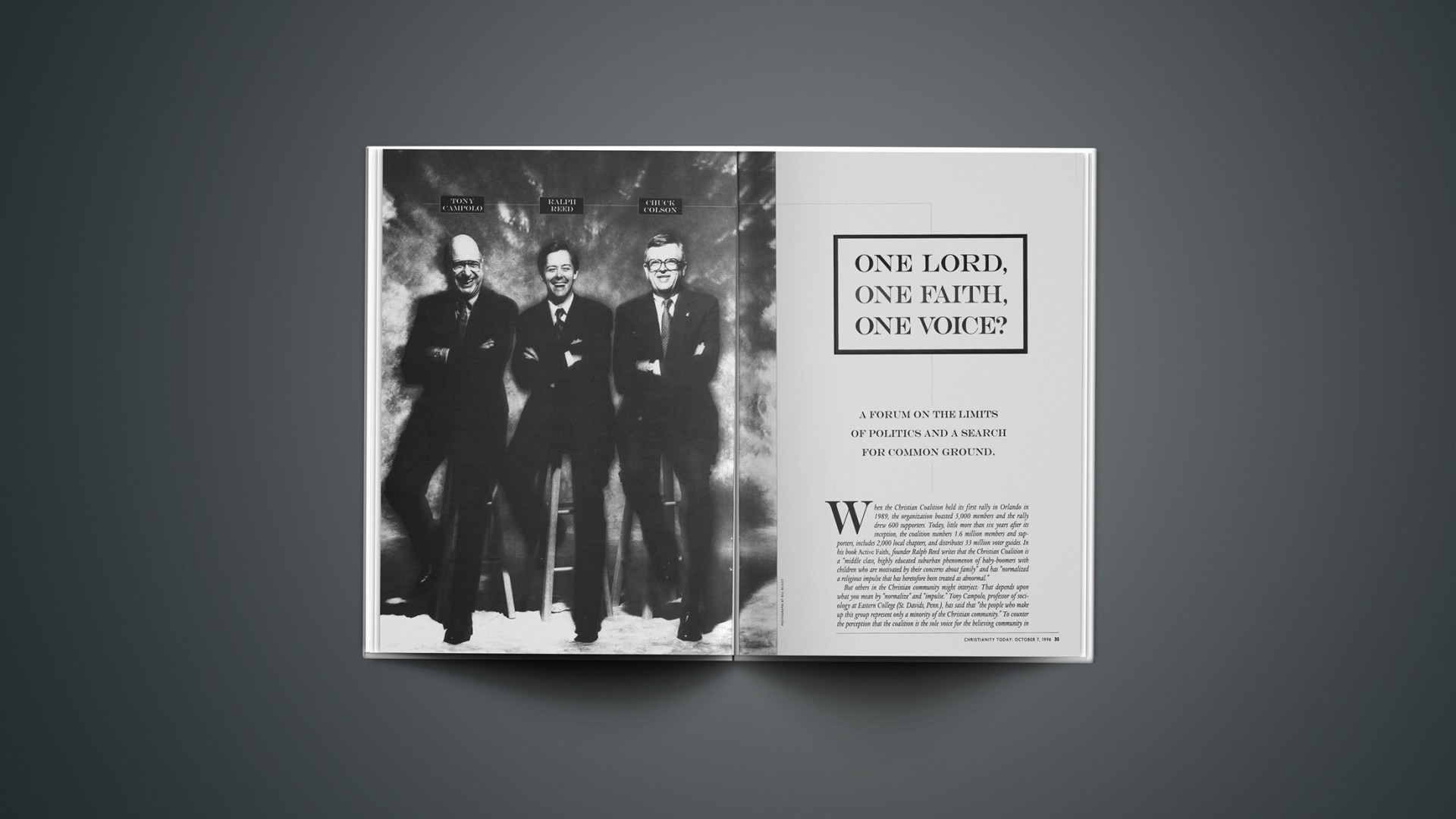

CHRISTIANITY TODAY felt the time had come to bring this cacaphony of voices together and try to move the discussion on the role of Christians in politics into new territory. In the spirit of unity, reconciliation, and accountability, we invited Christian leaders Ralph Reed, executive director of the Christian Coalition; Tony Campolo, sociologist, activist, author, speaker, and personal friend to President Clinton; and Charles Colson, founder of Prison Fellowship and Nixon White House insider, to join us in a forum to discuss the concerns raised on these and other fronts. Have political allegiances overridden the concern for a unified Christian witness? Can a distinction be made between those issues that Christians are compelled to address as a matter of conscience over against issues that arise out of political philosophy? Where should Christians agree and assert a unified voice?

Michael Cromartie, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C., and director of the center's Evangelical Studies Project, moderated the discussion, which included this joke from Tony Campolo: "Somebody is drowning 100 yards off shore. A Republican throws out 50 yards of rope and says, 'We've done our part, you have to do yours.' A Democrat throws out 200 yards of rope and drops his end."

POLITICIZED EVANGELICALS Recently the director of the Pew Resource Center said, "The conservatism of white evangelicals is the most powerful political force in the country today." The center released a survey in June that found evangelicals had increased their strength to 23 percent of the electorate, up from 19 percent in 1987. What is the reason for this?

Ralph Reed: If anything, the Pew Foundation study understates the size of the constituency. They assume equal turnout across the board. If you take "likely" or "actual" voters, in 1992 it was 24 percent of the electorate; in 1994 it was 33 percent. It is the largest, the most dynamic, the most vibrant, and the most transformational force in American politics today.

This constituency was engaged in a self-imposed act of retreat from the political culture for three generations. Now it feels that the social pathologies have become so threatening to their families, their children, their churches, and their synagogues that they feel that they can't not be involved. It is no longer a choice; it is an obligation.

There's another part of that Pew study that is equally fascinating. If you look at the 1987 data, this constituency was about one-third Republican, one-third Democrat, one-third Independent. Today it is 42 percent Republican, 19-20 percent Democrat, and 25-30 percent Independent. This is the most significant movement of a constituency-remember these people voted overwhelmingly for Jimmy Carter in 1976-since the African-American vote switched from Republican to Democrat between 1932 and 1936.

Finally, they feel that the national Democratic party-and I want to emphasize the national Democratic party, because at the state and local level there is still a lot of involvement-is insensitive to, and in some cases hostile to, their values, their views, their faith, and religion as a political force.

Chuck Colson: I think the 23 or 24 percent figure is grossly exaggerated. It all depends on how you define evangelical. If you take "evangelical" as meaning someone reacting against the moral decline in America, 24 percent might be a realistic figure. If you look at [George] Barna's data, which tries to determine who are serious Christians, that number shrinks appreciably.

Clearly there's an emerging political movement on the Right of people who listen to Rush Limbaugh and have a knee-jerk reaction to the political agenda. It defines a political phenomenon that is occurring, but I don't think it defines the church or is a fair measure of the church.

Why it is happening seems very clear: People are reacting against the law being uprooted from its moral base in areas that are important to them, if only symbolically, like the right of voluntary student-led prayer.

Tony Campolo: The evangelical fundamentalism that I grew up in was politically inactive, and what stirred this sleeping giant was the abortion issue. I believe another reason evangelicals have become active politically is because of Ralph Reed and the Christian Coalition. Whether or not you agree with their positions, all of us as evangelicals have to be grateful to the coalition for raising political concerns as genuine religious concerns-that politics is far too serious a business to be left to politicians.

TOBACCO AND GAMBLING Tony, has the Democratic party been insensitive to the concerns of many evangelicals, as Ralph said?

Campolo: The Democratic party has got to do some good housecleaning of its value system. It made a big mistake in its last convention in not letting [Pennsylvania's pro-life governor] Bob Casey speak. And at this convention they're not going to make that mistake. Tony Hall (D-Ohio) is leading a coalition of 40 Democrats in Congress who are going to have their say.

But the reason some of us have organized the Call for Renewal as an alternative to the Christian Coalition is because we feel that the Christian Coalition has become too closely allied with the Republican party. We're talking about perception in the general society. I believe that if you were to ask people, they would say that evangelical Christianity equals Republicanism. We felt that it was time for a group to stand up and say it doesn't necessarily equal Republicanism, even though on many issues we would support the Republican agenda.

But I think that the Republicans are also insensitive to a large number of concerns of evangelicals. For instance, I think that political considerations have led the Christian Coalition to ignore environmental issues as a concern of Christians. Also, the Republican party has gotten in bed with the tobacco industry, and we don't feel that the Christian Coalition has been sufficiently negative on this issue. We feel they ought to be raising questions about people like Jesse Helms, who took $77,000 last year from the tobacco lobby. Here is an industry that, if we are pro-life, we have to be against.

Are you saying that abortion and smoking are morally equivalent?

Campolo: I would not, because at least the people who kill themselves with cigarette smoking do exercise some degree of choice. But one would argue that an industry that chooses to make people addicts before the age of 12 has a lot to answer for. We are appalled by an industry that destroys 450,000 Americans and a million people worldwide every year. And we would call upon our brothers and sisters in the coalition to join us in the opposition to the cigarette industry even as I would hope you would call us to join you on the abortion concern.

But it should be noted that 84 cents out of every dollar contributed by the tobacco industry for political campaigns goes to Republican candidates.

Colson: This year. Not last year or the year before. Factual precision here. While Bob Dole is hung with the tobacco industry because of some, I think, ill-advised statements, we ought to point out that the tobacco money has been spread around generously in both parties. So a plague on both your houses.

Reed: Tobacco is one of about three major issues that I would cite where we strenuously disagree with the national Republican party and have made it clear in public statements. We will be supporting legislation that will force this industry to be more responsible and that will protect children.

The second issue I would mention where we clearly disagree with the national Republican party, and for that matter the Democratic party, is the issue of gambling. Bob Dole has taken in excess of $400,000 in gambling money. The Republican National Committee has taken in in excess of a million, as has Bill Clinton. I've not heard a figure of prominence on the Religious Left criticize this administration for having done so. I have criticized both the rnc and the Dole campaign for taking that money. So our agenda is not a partisan agenda. There will be times when we will have to take on the Republican party as well. We're willing to do it.

But where were my liberal friends in the Christian community when Surgeon General Jocelyn Elders was calling for the legalization of drugs? She was using the bully pulpit of her office to advocate activity by young people-sexually and in terms of drugs-that is clearly destructive to children.

Campolo: What I hope comes out of this is a meeting in which we actually go to the public and say, Here are the things that the Left and the Right in the evangelical community are unified about, opposition to gambling and smoking being right on top of the list.

Do I take from what you are saying, Ralph, that you would be willing to put whether a politician takes money from the tobacco industry onto your voting guides for the upcoming election?

Reed: I'll take that under advisement, but I think it would be hard because, as Chuck accurately pointed out, both parties have taken money.

Campolo: But that's the point. We should condemn both parties for taking it.

Colson: To get back to the original question, the reason many Democrats have moved to the Republican party is the abortion issue and the gay-rights agenda, period. These are moral issues. Our consciences will not let us be compromised. And the Republicans have, to now, embraced those issues; and the Democrats have turned their backs on them, and that's why 10 million people have gone from being evangelical Democrats to being evangelical Republicans.

The big question is, Will they stay there? I think that exodus of evangelicals into the Republican party might stop dead in its tracks if Dole keeps suggesting that moral issues like abortion are subjective, and something like tax policy is nonnegotiable. Ralph's troops will shrivel up.

RACE The Pew study found that 34 percent of black Christians think Republicans care more about religion than Democrats do. Does this represent an opportunity for religious conservatives to pull the African-American community away from the Democratic constituency?

Reed: I think the answer is yes and no. The truth is that the African American church is one of the most conservative social institutions in America today. They are a lot tougher on welfare, drugs, and crime than I would ever dream of being because of what it's done to their communities and families they're trying to shepherd. There's extensive polling data available that show that Latinos and African Americans are more conservative than whites on issues like welfare, crime, school prayer, and abortion. The African-American community is in favor of school choice, and the white community is ambivalent about it because their kids already go to the good schools; and it is the Latinos and the African Americans in the inner city who are for school choice and a voucher program. So there are opportunities.

On the other hand, we've got a long way to go. The legacy of Jim Crow segregation and racism that the white evangelical community still carries is like an albatross, and there is a chasm of a very painful history that we've still got to bridge. I think Promise Keepers making racial reconciliation one of the seven promises is a very hopeful sign, as is the Southern Baptist Convention's recent public apology for its past complicity in slavery, racism, and Jim Crow.

Still, when Bill Clinton said that he was going to go to that black church in South Carolina and pray at the dedication ceremony after it was rebuilt and was criticized by some Republicans for having done so, that was an example, to me, of where Republicans didn't understand the issue. The Christian Coalition, and I think the conservative evangelical community more broadly considered, is going to make this a bigger part of its agenda in years to come.

Campolo: I think both Ralph and I would probably join in saying that our biggest concern is not whether the African-American community moves to the Democratic or the Republican party. Our concern is that their greatest linkage right now is to the Nation of Islam. When [Louis] Farrakhan emerges instead of an evangelical black pastor as the prime spokesperson for the black community, we are concerned and are looking at where we have failed.

The African-American community has negative attitudes toward evangelicals and toward conservative politics. Whether they're right or whether they're wrong, the question you raise is, Do you expect there to be a strong movement in the African-American community over to the Republican party? Probably not, because they're carrying a lot of baggage from the past. Conservatives in the past have denounced the heroes of the African-American community, specifically Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King. Also, gun control is a great concern in the black community. The fact that conservatives support the right of people to own attack weapons keeps African Americans out of their camp.

Colson: We should all be worried about the movement to Farrakhan, who is an outrageous demagogue and one of the most dangerous men who has come along in a long time in American life. And we should be much more concerned about that than whether they're Republicans or Democrats.

Reed: The Bible teaches that sometimes you've got to go back and do your first works over again before you can move on in your walk with Christ. I think this was an area of social justice where many-not all-in the white evangelical community were dead wrong. And until we fully repent of that and, as a community, become more aggressively biracial and multiracial in our aspirations for the nation and for the faith community, I do not believe that God will bless our efforts on issues like religious freedom, school prayer, or abortion.

One of the most powerful moments I've had in my entire political life was holding hands with black pastors and praying at our summit [regarding the church burnings] in Atlanta. And you could sense a curse breaking on this community, because we've been an almost exclusively white movement. I'm not saying that everybody in the movement is racist; that's not fair. But I do think that we've got to build those kinds of bridges. And I think there are some emerging figures in the Republican party who can play a role in this regard.

THE LIMITS OF GOVERNMENT Aren't there some issues the legal and political realm simply can't address?

Reed: The first book other than the Bible that I read after I became a Christian was Born Again, by Chuck Colson. I think God wanted me to read that book, because it was the story of someone who wanted to change the world and tried to do it through politics and came to a point where he saw that politics wasn't the answer. That book changed my life, because up until I got saved I thought the same thing. If we could just elect the Gipper, if we could just cut the marginal tax rate, if we could just get rid of the Soviet empire, it would be a great world.

I want to instill in the hearts and minds of activists that you should not make your political involvement the sole repository of your hopes and aspirations as a Christian for the reformation of society.

Colson: I think 95 percent of the things that are ailing our country today, that most of us feel passionately about, are beyond the reach of government. And I think we have lived in an era of political illusion where we believed there were political solutions to all problems. Politicians feed this. They can come on television and say, "Elect me. I'm going to solve this problem." Actually, they have very little that they can control, as I discovered after four years in the White House. If you want to penetrate the moral imagination, you don't do that with legislation.

Reed: The reality is that the limits of politics are great and large. And I think Christians who get involved in the political process because they want to usher in a millennial kingdom or establish justice and righteousness in this world are going to experience a tremendous amount of frustration.

My call for political involvement is based on a biblical doctrine of citizenship that we should be salt and light. An extension of that call is civic involvement in a fallen world. But to attempt to take theological precepts, even broadly defined, and legislate them on people who do not share those in their hearts is a recipe for disaster. It's not only bad politics, it's bad theology.

Having said that, I do think there's a real role for political involvement. Martin Luther King said, "I cannot pass a law that will force the white man to love me, but I can pass a law to stop him from lynching me." I may not be able to pass a law that says to somebody, Don't drink and beat your wife and mistreat your children, but I can pass a law that says, If you drink and get behind the wheel of a car, we're going to take your driver's license away, and we're going to put you in jail. You're conceding that you can't usher in the kingdom through political involvement, but recognizing the obligation to try and protect the innocent.

The question is, Where do you draw that line?

Colson: It is George Will's argument that if one person drinks, that is his or her business. If a whole society drinks, it becomes society's business. And maybe that's where that line gets drawn. In a society that lives with the experiment of a certain tension between order and liberty, you want to allow the maximum liberty you can, consistent with preserving order. It's always going to be a pendulum that swings back and forth.

I think the question lies in striking that balance between order and liberty, which is what our founders wrestled with. The grave danger of the libertarian and libertine lifestyles that we have demanded-as Michael Sandel says, "the pursuit of the unencumbered self in the sixties until today"-tilts that balance way over. The Supreme Court had to construct a legal fiction in order to satisfy the sacrament of the sixties on the basis of the implied right of privacy.

My worry about the Christian Coalition or the Call for Renewal or any other group that is organized as a Christian political movement is that we're focusing the church on redressing that balance through political means, which, to me, is a very limited remedy. It is going to take a profound cultural transformation in this country. The critical question "How shall we live?" has got to be decided by the people in the great apologetic over the backyard fence.

Reed: I certainly don't disagree with that, but I think it still begs the question-if you go to Washington, D.C., and you see the large buildings devoted to the entrenched lobbying interests of the aclu and the labor unions and the veteran organizations and the business groups-does faith have a voice in that process? We are trying to be that voice. We are not trying to speak for the church or to suggest that our political involvement is the sum total of the church's mission on earth.

Campolo: I believe that one of the purposes of law is to instruct, and not just to control, the people. And so the civil-rights legislation may not have corrected the problems of racial discrimination in this country, but it sent a clear message as to what was morally right and morally wrong.

I think that the liberal political establishment has been humbled over the last decade, and justifiably so, because we tended to believe that government was the instrument to bring about social justice in this society. During the sixties when liberal Christians got involved in politics, it meant that they marched on Washington and said, You must create justice and help the poor and reach out to people in the Third World. They saw government as the primary instrument for addressing social problems.

I'm now worried about the other extreme that suggests that the church alone can get the job done. And I hear this emerging ideology that suggests that government should not be involved at all in trying to achieve social good. The Bible is very clear about those who are in positions of political power using government to help the poor-Psalm 72, Amos 5, Jeremiah 22, Ezekiel 34, Daniel 4.

Has the church become too politicized both on the Right and the Left?

Campolo: I think the general public has the sense that evangelicals want to take over the government and impose Christian values on the rest of this pluralistic society. When you say we just want to have our voice heard, and we don't want to be discriminated against as Christians have been in the past, I think you're on target. But there's a growing cynicism among those of us in the Call for Renewal. We pick up the "Contract with the American Family" [booklet] and read on page 18: "The Christian Coalition's top legislative priority since 1993 has been tax relief for America's hard working families." Now, I'm wondering. Are you guys pro-life? Or are you guys simply Republicans looking for tax relief?

Reed: When Bill Clinton came to office in 1993, we announced that our number-one priority was to reduce the crushing tax burden on the American family. Now, was that because that was the most important issue in the hierarchy of our values? No. It was because we recognized that this was an issue that we cared about and that President Clinton also cared about, and we felt we could get some movement. And so we proposed a $500-per-child tax credit, which President Clinton has vetoed twice.

Now, I wouldn't argue that there's a biblical mandate for lower taxes on the family, but I will say that the crushing tax burden on Americans has been hurtful of the family. I think there are a lot of women who have been driven out of the home into the work force, not because they wanted to be, but because they had to support the family. And one of the reasons for that has been the tax burden.

Campolo: Mainline churches are now bearing the consequences of making the Democratic party agenda the message from the pulpit all during the sixties and seventies. The reactions were severe. Now the evangelical church stands in the same danger of making the agenda of the Republican party the message from the pulpit. George Bernard Shaw once said, "God created us in his image, and we decided to return the favor." And as I hear Jesus being proclaimed from one end of this country to the other, he is increasingly coming across as a white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant Republican; and that's what scares me.

I find increasingly the rhetoric of "welfare mothers" in political dialogue. And that, to me, has racist overtones. America has learned to talk in code. "Willie Horton" had a meaning to it, and "welfare mothers" has a meaning to it. I don't like hearing those kinds of words on religious television. Ralph, you've spoken to this eloquently in your book, that within the Religious Right there is rhetoric emerging that has to be stilled and dealt with. You have done well to speak out against that in saying that unless we evangelicals start talking right, we are going to lose much more than we will ever gain in this political process.

Another fear I have is that, for the first time, Christians are beginning to taste political power. And power has a very corrupting influence on people. I am concerned that whenever Christians operate from a position of power rather than from a position of servanthood, they betray the gospel and become something other than what Christ wants them to be. How to hold power and express love simultaneously is beyond my understanding and imagination, and that's why I'm scared whenever we come to politics. I'm afraid of what we'll do with power, and I'm afraid of what it will do to us.

Colson: There is a risk that the gospel will be held hostage by a political party, that we are so anxious to get our views across that we'll compromise and hedge and end up being in their pocket, or being perceived as being in their pocket. I think the grave danger is that once you create a Christian political movement you almost are doomed, Left or Right, to associate the gospel with a particular political agenda. And in our culture, with the press so heavily secularized, the Christian agenda gets submerged and the political agenda looms large.

The so-called New Religious Right is the bogeyman of American political life. And it is a tragedy, because there are moral issues that compel us as Christians to be in the debate. We not only deserve a place at the table, we have historically provided the moral consensus that allows limited government to exist, not just as individuals, but as a Christian political movement. Wilberforce had an openly Christian political movement to bring an end to slavery. And to me, abortion is a moral equivalent of slavery today. And so Christians belong in there with a Christian banner flying.

The fact that I'm a Christian and am trying to bring my views to bear in the political marketplace does not mean that my views are illegitimate because they are motivated by deeply held moral concerns. The other side has got a moral agenda of its own-it's simply not recognized as such. All legislation is going to be morally based and have moral implications and affect moral behavior.

My grave fear is that after a disillusioning 1996-which I think is going to be inevitably very disillusioning to Christians-that they will be drawn to the notion that we should retreat from the political process, disengage, not stain ourselves with the sin of the world, but go back to building up our churches and be the resident aliens that we always are in every society. I fear that as Christians we'll withdraw from the political arena and no longer argue those moral issues. Then the cultural decay in America simply hastens, and the church loses its effectiveness.

Reed: Have Christians become too politicized? I think the answer is no. Christ numbered among his disciples Matthew, who was a tax collector for the Romans and considered a traitor to the cause of Zionism, and Simon the Zealot, who was a member of a terrorist political party devoted to the violent overthrow of the empire. I find it hard to believe that there weren't some fairly fractious political debates going on around those campfires when Christ was alone with his disciples after they had fed people and sent them out.

I am pleased that groups like the Call for Renewal and other groups on the Left have begun to become energized. Because the truth of the matter is, I don't want people to equate the church with the Christian Coalition. That would be wrong.

I don't share the same fear that Chuck does about the reaction to the 1996 election, and let me tell you why. The momentum in a conservative, religious, and moral direction of our politics is so overwhelming that no matter what happens in the presidential election level, the Republicans are likely to retain control of both houses of Congress and perhaps build on those majorities. And no matter what happens at the congressional level, my sense is that what happened in 1992 and 1994 will be repeated, and that is that you'll see huge gains by religious conservatives in school boards, city councils, state legislatures, county commissions, and other local offices.

And so I don't think they'll withdraw. I think there will be some disappointment no matter what happens. But underneath, where people live, there will continue to be significant and historic gains by this community that are irreversible.

Campolo: I think we are becoming too politicized. An example of this is found in the voter guides being put out by the Christian Coalition. These guides do not tell us as much about the Christian values of the candidates as much as they tell us how Republican they are. As a case in point, Tony Hall, a Democrat, who almost everyone agrees is one of the finest Christians in Congress, gets a 31 percent rating in the coalition's voter guide. This in spite of the fact that he got a 100 percent rating by both the Family Research Council and the National Right to Life Council. His only sin seems to be that he strongly supports appropriations to help the poor in Third World countries. But the coalition gives Helen Chenoweth (R-Idaho) a 100 percent rating in spite of the fact she endorses the militia movement.

Colson: I think Tony has raised a very good question, and it points to a fundamental problem with trying to create a broadbased political movement and call it Christian. I would endorse Tony Hall any chance I get. I think it is terrible for us to us to turn our back on an evangelical brother who is with us on the issues.

Don't we have to ask the fundamental question, What is government's role? Tony cites all the Old Testament passages-and I like to use them whenever they fit my own criminal justice agenda. But I do it with an awareness of my own hypocrisy because I don't believe in theocracy, which is what Israel was in the Old Testament. I'm not a reconstructionist or a theonomist. And so when I look at those passages, all I can do is reflect on the character of God.

I think a Christian needs to look at government and say what is government's role in a pluralistic environment in a New Testament perspective. And it isn't, as Muggeridge said, to abandon any interest in government, but rather it is to see that government performs the fundamental function, which is clear in the Bible: to restrain sin, promote justice, and preserve order.

God obviously passionately cares about the poor and the suffering. But I don't think God designed the kind of utopian system that this country embraced in the sixties and seventies that we've now found to be completely bankrupt. And for some now to embrace the utopianism of the Right would be an equal catastrophe. I think it was our friend at Boston University, Glenn Loury, who said he's seen utopianism of the Right, and it is not any prettier than the utopianism of the Left.

GAY RIGHTS AND THE SUPREME COURT This year the Supreme Court in Romer v. Evans struck down Colorado's attempt to stop antidiscrimination laws based on so-called sexual discrimination. It suggests that any opposition to these laws was based on "animus." How does each of you feel about the implications of the Romer decision?

Colson: Romer v. Evans is the unraveling of the rule of law in America. It is the end of connecting the law to any objective standard or natural law to which man-made law must be responsible. The decision is so shocking that it is hard for me, having taken my doctorate in constitutional law, even to talk about it.

Justice Kennedy said that the action of the Colorado voters raised the inevitable inference of animus and reflected bias motivated by their religious convictions. He did that without a single finding of fact on the record. As a matter of fact, the findings on the record were precisely the reverse. Governor Romer said that they were not motivated by religious bias or by any antihomosexual beliefs but simply that they did not want to extend civil-rights protection to sexual classification. They don't want to make whether you get civil-rights protection a question of who you sleep with at night.

Romer v. Evans makes it impossible for the Supreme Court not to approve same-sex marriages in the sense that any time you would vote to prohibit them you have raised the inference of animus. Liberty, as defined in Casey v. Planned Parenthood, means everybody is entitled to find for him- or herself the mystery and meaning of life. And so it is very hard to legislate public policy when that becomes the standard of the Court.

It also means, if you take Romer v. Evans, if you take Compassion in Dying v. Washington, if you take Casey v. Planned Parenthood and wrap them together, that sodomy will be considered a constitutionally protected liberty, and laws against it will be unconstitutional. And if there are no laws against sodomy, polygamy has to go next. No laws against sodomy, polygamy-probably no laws against incest-can survive this avalanche, and then there is no compelling state interest in banning same sex marriage.

The only thing that could possibly stop them is a constitutional amendment. If I were looking for a good issue in the Congress right now, I'd be talking about a constitutional amendment to define marriage as being between a man and a woman; because normal legislation will be dispensed with the back of Justice Kennedy's hand.

This is the biggest shift in the culture war yet. This is the mother of all battles, and it has been decided six to three. There is no appeal. I care less about the Colorado statute than I care about the legal reasoning that struck it down, because it will make the formulation of any public policy based on moral values impossible in the future.

Reed: Clearly, I disagree with the Romer decision. I think it was wrongly decided. I agree with Chuck. It was probably the most specious and threadbare legal reasoning that I've read in a Supreme Court decision since Lee v. Weisman, which was equally absurd. The Court has, through judicial fiat, said that no state, no municipality, no government can prevent the extension of civil-rights protection based on a sexual preference. I have no rights as a heterosexual. If my boss calls me in tomorrow and says, "I really don't want you around any more because you're a heterosexual," I have no legal recourse under the civil-rights statutes. Now, if he dismisses me because of the color of my skin, my ethnicity, my gender, I do. And my opposition to the granting of civil-rights protection based on one's sexual proclivity is that it is a Pandora's box. Does a sadomasochist, a polygamist, or an adulterer have the same rights?

Campolo: What you have stated shows the bankruptcy of politics in many respects, because that Supreme Court decision that you correctly say has such far-reaching effects is by a Supreme Court in which the opinion was written by a conservative Republican appointee.

But I think Chuck is a bit alarmist when he sees the gay civil-rights movement in these severe terms. The American family is in serious trouble. Divorce rates are at astronomical levels. Desertion rates are scaring everybody to death. But the problem with the American family is not due to gays wanting to live together in committed relationships. I'm not endorsing this, but the gays want to get married. It is the heterosexuals who want to get divorced. We're beating up on gays for what is, in fact, a problem in America in general. There's something wrong with a society when one of two people who have lived together for 25 years can be prohibited from being at the other's deathbed because the family says he or she has no rights. I am worried that there are referendums all across this country that are aimed at limiting what I consider to be the legitimate rights of gays. And I worry that we end up looking to the world as a group of gay-bashing, insensitive people who are the enemies of the gay community. We are not. You are not.

On the other hand, when we talk about family values, I find very little being said about what is going on in our own churches with the acceptance of divorce and the acceptance of the breakdown of the family. I find that ministers are lowering their voices on this issue as they try to raise their budgets. It's frightening.

Colson: I'm talking about the Court decision. It didn't matter that the issue was homosexuality. My concern lies in the fact that the Court legislated in the way that suggests that the very act of legislating restrictions on someone's sexual behavior raises an inference of animus-that it's automatically bias. Heterosexuals living outside of marriage are denied spousal benefits in the Disney Company. Homosexuals living outside marriage get them. So there is a favoritism toward homosexuals.

Court decisions have brought the culture war to a screeching halt, because there will not be another case that can be won in the Supreme Court with the present state of the law in Romer v. Evans. That was why Scalia wrote his blistering dissent and read it from the bench. Scalia recognized that the game is over. The door is closed in the Supreme Court.

And that raises profound questions for the viability of Christian political movements and about same-sex marriage and its impact on the sanctity of the family. And it raises profound questions about how you respond, because only a constitutional amendment or open defiance of the Supreme Court is going to stop the steamroller that is heading for us.

PARTIAL-BIRTH ABORTIONS Recently President Clinton vetoed the partial-birth abortion act. Sen. Patrick Moynihahn said that this was tantamount to a policy that would lead to infanticide. Is this a sobering decision or not?

Campolo: I was very upset by the President's veto. I called Chuck and talked to him about it. It is interesting that on this issue a significant proportion of the pro-choice people were upset. There were a lot of pro-choice people who would argue that early stages of pregnancy are different from this late stage. I'm not going to go into the ontological arguments about all of this, but there is a kind of gut reaction across the country that these late-term abortions are wrong. This may have been a rather disastrous decision on the part of the President in terms of his re-election. I think he's going to find a tremendous mobilization among people who otherwise might have supported his pro-choice stance, particularly the Roman Catholic community.

Colson: I think the partial-birth abortion ban act is a crossroads for evangelicals and conservative Catholics in this country. If the issue had never been raised, one could not say that this country endorses infanticide. Once the issue to outlaw it was raised, the President vetoed it. If that veto is not overridden, then this country has taken an action tantamount to approving infanticide. The Holy See spoke to that in an unprecedented statement. I've been unhappy that evangelicals haven't spoken with equal vigor.

One cardinal in the Roman Catholic church talks about this being a basis for civil disobedience. Christians have reached a point where we have to ask ourselves, Can we give the kind of support that has been the backbone of civil religion in America to a government that sanctions infanticide?

I think the biggest question that the Christian movement will have to wrestle with in the light of Romer v. Evans--the door being shut in the Supreme Court-and a nation embracing infanticide is whether we can lend moral legitimacy to this government.

Reed: I don't think you can blame the religious conservative community for its involvement in the only pro-life party in America today when one of the two political parties countenances an act that the Catholic bishops have properly equated with infanticide.

UNITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY Let's pretend for a moment that each of you attends the same church. Would you be able to make it clear to others that your faith is more important than your politics?

Reed: I am concerned about the quality of our witness and how we speak to the world about each other. To have Christians on the Left referring to conservative brothers and sisters in Christ as extremists or radicals is very destructive, even if we're worshiping together. There have been some on the Religious Left that have been critical of our involvement in the church-burnings issue, suggesting that our motives were impure, which I find extraordinary. This doesn't really bother me very much on a political level, but it bothers me a great deal as a Christian. The Religious Left seems to have as its sole function releasing a bunch of white papers criticizing us as an organization and as a community. I don't see that as a strong witness. And it's really not politically effective, because you become viewed as a sour-faced critic of someone else who's building and changing things. I would say the same thing of people on the Right.

In my book [Active Faith, Free Press, 1996] I issue a call for civility. And I had some of my dear friends in the conservative community who were very upset about it. But I'm glad I said it.

Campolo: I think the three of us have to make a commitment to hold our brothers and sisters who are associated with us accountable. I don't expect you to be the one to come over and say to the members of the Call for Renewal, "You're making some statements that are out of line." That becomes my responsibility. And I would hope that the same would be the case for you-that we become committed in the name of Jesus Christ to holding people accountable to speak the truth in love, as the Scripture says. So that the kind of rhetoric that could ruin our witness from one end of this country to the other doesn't take place.

Colson: If we were in the same church, could I be in fellowship with both of these guys? The answer is yes. You forget that I was discipled by Harold Hughes. He was a liberal Democrat then. He's even crustier and saltier about it now than he ever was. I can love them without saying I'll vote for them.

I think out of this discussion we are left with a couple of questions that need to be dealt with by the Christian world. One of them is whether Christians will, in disillusionment, give up on the political arena. The second question is whether Christians can bear allegiance to a government that sanctions infanticide and may soon undermine the first institution God created, the family. The third-and I think both of these guys are shying away from it-is agreeing that there are a lot of legitimate negotiable political issues that Ralph Reed, as a conservative Republican, and Tony Campolo, as a liberal Democrat, can be involved in. But when you hang the Christian label on them you divide the body of Christ, and you run the grave risk that you're going to bring the gospel hostage to the fortunes of one political party, Left or Right.

God wants justice. The biblical word in Hebrew is tsedekah, which means righteousness. And so our job is to bring righteousness to bear in all of public life. That may sometimes cut against the Republican grain and other times cut against the Democratic grain, but we're free to do that. And we should fight hard not to allow the media to stereotype us. I'd go to some lengths to reassert the independence of the gospel and not ever let it become hostage to either political party.

What Christians ought to be doing is striving to find those nonnegotiable issues, fundamental biblical questions that are not Left or Right issues, that our Christian commitment compels us to act upon.

What are some nonnegotiables that the Christian community should be unified around?

Colson: The issue of life is absolutely central. The issue of righteousness in public life is also a Christian issue-the kind of thing that motivated Wilberforce when he conducted the campaign against the slave trade-calling for righteous living and a reformation of manners among people and their political issues. The sanctity of marriage and the defense of the family is another. If the steamroller coming through the courts legalizes gay marriages and society says this is normative, it is undermining God's first institution. And also, the whole question of compassion and concern for the poor and the oppressed is always a fundamental Christian issue. The government has a role in this, but in the past it has snuffed out the role of the church.

Do you others agree with Chuck's nonnegotiables?

Reed: Absolutely.

Campolo: In answer to the question, Could we all worship in the same church, in the course of this afternoon I am convinced that we do all worship in the same church. And that is the good news that we have to communicate to people from one end of this country to the other.

Copyright © 1996 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Last Updated: October 2, 1996