One of the most stirring martyrdoms recorded in church history is Polycarp’s. When the venerable bishop of Smyrna (modern-day Izmir, in Turkey) heard the Romans were planning to arrest him, he heeded his friends’ advice and withdrew to a small estate outside of town. But while in prayer there, he had a vision. “I must be burned alive,” he told his friends. When the soldiers arrived, his friends once more urged him to run, but Polycarp answered, “God’s will be done.”

After being escorted to the proconsul, Polycarp carried on a witty dialogue with his questioner, who flew into a rage and threatened Polycarp with death by fire. “The fire you threaten burns but an hour and is quenched after a little,” Polycarp answered; “for you do not know the fire of coming judgment, and everlasting punishment, that is laid up for the impious. But why do you delay? Come, do what you will.”

At the execution scene the soldiers began to secure him to the stake, but Polycarp stopped them: “Leave me as I am. For he who grants me to endure the fire will enable me also to remain on the pyre unmoved, without the security you desire from nails.” He prayed and the fire was lit. The second-century chronicler of this martyrdom said it was “not as burning flesh but as bread baking or as gold and silver refined in a furnace.” The martyrdom, he added, was remembered by “everyone”—”he is even spoken of by the heathen in every place.”

Calm demeanor. Courageous words. A death noted by unbelievers. One can’t help admiring this type of martyrdom and feeling ennobled and encouraged by it. Unfortunately, not all martyr stories are so inspiring.

There were about 300,000 baptized believers in Japan at the end of the 1500s, thanks to the efforts of Catholic missionaries. But in 1614, the Japanese emperor decreed: “The Kirishitan [Christian] band have come to Japan, not only sending their merchant vessels to exchange commodities but also longing to disseminate an evil law, to overthrow true doctrine, so that they may change the government of the country and obtain possession of the land. This is the germ of great disaster and must be crushed.”

When the fury was unleashed, crucifixion was the preferred method of execution. On one occasion, 70 Japanese were crucified upside down on the beach at low tide. As the tide rolled in, wave after wave, the water lapped at the Christians’ hair, then their foreheads, and finally their noses and mouths, until all 70 were drowned.

A relentless, ferocious persecution was carried out for years, so that by 1630 nearly all Christians had been killed or had committed apostasy. “Christianity in Japan had been destroyed,” wrote missions historian Stephen Neill.

A small remnant remained, however—hidden, scared, constantly looking over their shoulders, never daring to tell any but the closest loved ones of their true beliefs. In such an insular atmosphere, their beliefs slowly metamorphosed: within three generations, the Trinity had become Father, Mother Mary, and Christ the Son. The children’s children remembered that Jesus had died on a cross, but they didn’t know why he had died.

Apostasy. Ineffectual witness. Theological decline. The obliteration of a church. Though a regular feature of the church’s history, these are not the kinds of martyr stories we love to hear about or talk about. Why is that?

Obviously, these kinds of stories don’t make for good sell copy—”Christians Killed, Church Dies”—or good devotional material—”Sometimes, when Christians are martyred, the bad guys win!”

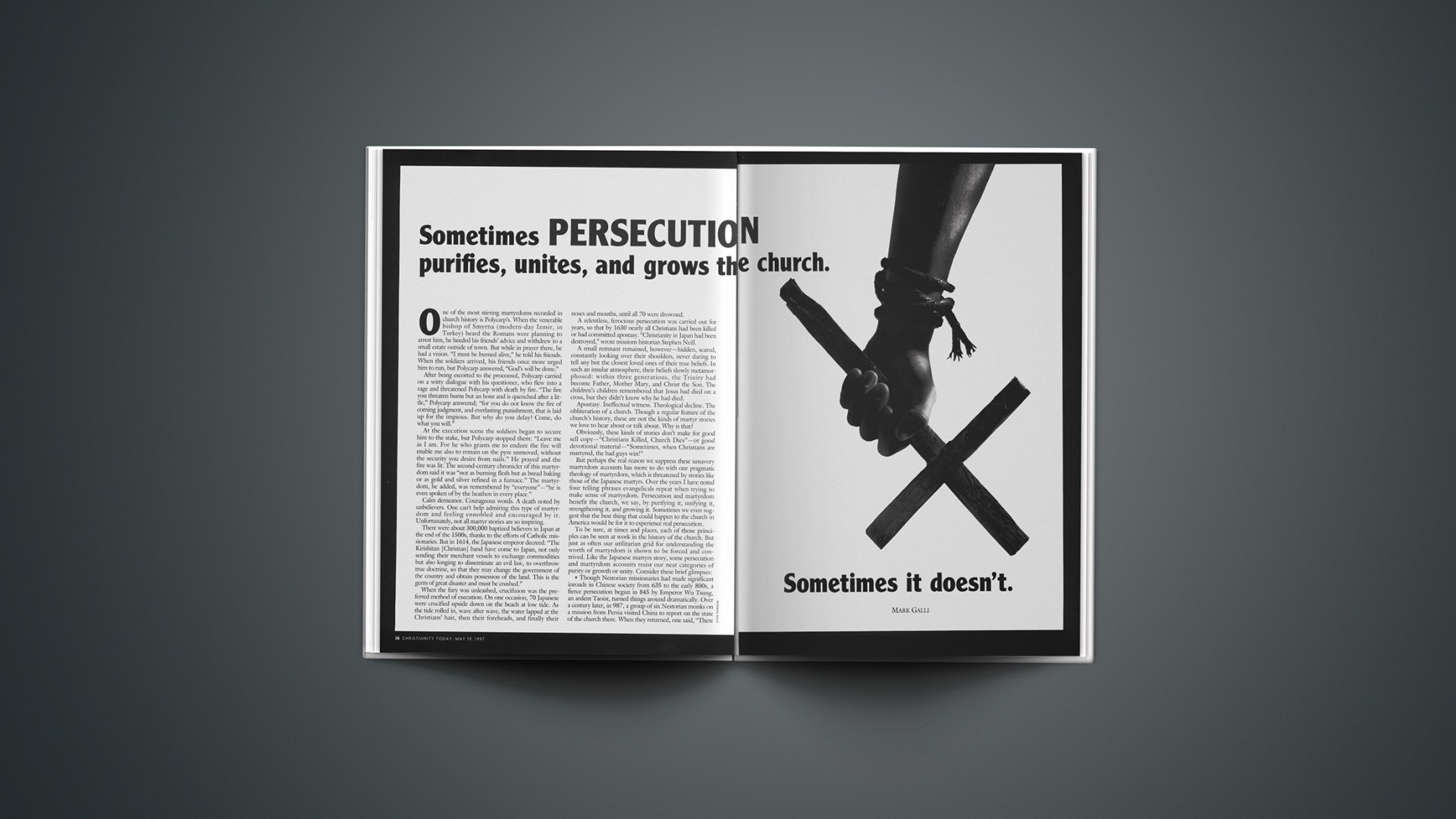

But perhaps the real reason we suppress these unsavory martyrdom accounts has more to do with our pragmatic theology of martyrdom, which is threatened by stories like those of the Japanese martyrs. Over the years I have noted four telling phrases evangelicals repeat when trying to make sense of martyrdom. Persecution and martyrdom benefit the church, we say, by purifying it, unifying it, strengthening it, and growing it. Sometimes we even suggest that the best thing that could happen to the church in America would be for it to experience real persecution.

To be sure, at times and places, each of those principles can be seen at work in the history of the church. But just as often our utilitarian grid for understanding the worth of martyrdom is shown to be forced and contrived. Like the Japanese martyrs story, some persecution and martyrdom accounts resist our neat categories of purity or growth or unity. Consider these brief glimpses:

—Though Nestorian missionaries had made significant inroads in Chinese society from 635 to the early 800s, a fierce persecution begun in 845 by Emperor Wu Tsung, an ardent Taoist, turned things around dramatically. Over a century later, in 987, a group of six Nestorian monks on a mission from Persia visited China to report on the state of the church there. When they returned, one said, “There is not a single Christian left in China.” So fierce and thorough was the persecution that no one was left even to tell the stories of martyrdom.

—In 1453, one of the greatest missionary churches in our history suddenly stopped doing evangelism because of persecution. Eastern Orthodox missionaries had evangelized all the Slavic countries (through Cyril and Methodius) as well as Russia. But by the mid-1400s, Eastern churches were doubly paralyzed: on the one hand, Islam had aggressively advanced through Asia Minor almost to the heart of Christian Europe; on the other, pagan Tartars were invading Russia. The capture of Constantinople in 1453 marked the end of the Eastern Empire and, as Stephen Neill noted, “the end of the great missionary history of the Greek-speaking churches.”

—North Africa was once the home of a vibrant Christianity and of the most influential Christians of the early church: Tertullian of Carthage, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, and Augustine of Hippo, to name a few. But with the coming of Islam to the region in the late 600s, a steady, quiet, but relentless persecution (military, economic, and social) over hundreds of years wiped the church out of many areas. In 700 there were about 30 to 40 Christian bishops in the Maghrib (northwest Africa). By 1050, there were 6 left; by 1300, 1. By 1400, none.

The fact is that some persecutions are successful. Some martyrdoms do not unify or purify or grow the church. Sometimes in some regions for long periods of time, the gates of hell prevail against the church.

Herbert Schlossberg, in his book Called to Suffer, Called to Triumph: Eighteen True Stories of Persecuted Christians, writes, “People who grow rhapsodic about the ‘purity’ of the persecuted church are not likely to have seen much of it. … Christians living in countries of persecution … show a confusing combination of saintliness and sin, courage and fear, wisdom and foolishness—just as we ought to expect.”

Presbyterian missiologist Samuel Moffett offers an apt, if depressing, metaphor: “Sharp persecution breaks off only the tips of the branches. It produces martyrs and the tree still grows. Never-ending social and political repression, on the other hand, starves the roots; it stifles evangelism and the church declines.”

So how are we to understand these martyrdoms in which none of the good we expect comes about: Are they failed martyrdoms, or is it our theology that is failing these unsung heroes of the faith?

Learning from the early church Recently I reviewed the writings by and about the early church martyrs and was surprised to find how relevant their insights were for understanding “pointless” martyrdoms and persecutions.

For the early church, the bottom line of martyrdom was not the pragmatic improvement of ecclesiastical life but the spiritual regeneration of the people of God. As Paul put it, martyrs “complete the sufferings of Christ.” Or, more simply, martyrs redeem the church.

This is startling to Protestant sensibilities, but we don’t have to understand this as some propitiatory exchange that adds something to the work of Christ (which is what some early church writers implied). Instead, martyrdom is an act of faith that re-presents key elements of the gospel to us. That, in turn, helps redeem us from our bondage to a myopic and weak faith and to enjoy afresh the saving work of Christ.

This re-presenting of the gospel happens at four levels:

First, in martyrdom we see again the power and destructiveness of evil. In our one-dimensional age, we are apt to blame persecution on a pernicious form of government (communism, fascism), or on the intolerance of another religion (Islam), or on the wickedness of some individual (Idi Amin). The early church knew better. W. H. C. Frend, in his monumental study of early martyrs, Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church: A Study of a Conflict from the Maccabees to Donatus, observed, “There is no evidence that the Christians regarded their quarrel specifically with the authorities, let alone with the Roman Empire. … The Devil was their enemy. … The Devil ‘fighting with all his strength,’ was the active agent of mischief.”

The early church knew that, most of the time, the Devil stalks quietly, slyly, as a wolf in sheep’s clothing. During severe persecution, though, he roars and claws, and foolishly shows his colors, making it plain what he is about: working feverishly, madly, dreadfully to roll back the advances of the gospel.

This clear-headed world-view is grounded, of course, in the New Testament. Even when the New Testament writers refer to “rulers and authorities,” they speak of spiritual forces. “For our struggle,” Paul wrote, “is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Eph. 6:12, NRSV).

Especially the “ineffective” martyrs, whose deaths we cannot remember and whose only legacy was a destroyed church, help us see the ugly reality of this present darkness.

The early church was also clear that for all the Devil’s temporal power, the Devil cannot win, and that, ironically, every time he seems to win, he actually loses. Tertullian wrote, “We conquer in dying; we go forth victorious at the very time we are subdued.” Early Christians were gleeful about this turn of the spiritual tables, a glee based again on biblical revelation: “Death has been swallowed up in victory!”

The Devil’s defeat Second, in the early church, the day of a martyr’s death was celebrated as his or her “birthday,” the day new life with Christ in heaven began. When it came to the assurance of salvation, the early church taught that martyrdom was the guarantee. Tertullian said, “Your blood is the key to Paradise.”

This connection between martyrdom and heaven was strong indeed. In fact, the early church had a hard time holding back voluntary martyrs, men and women who deliberately provoked authorities or threw themselves on the stake to die for Christ.

For example, in about a.d. 170, at Pergamum, on the coast of Asia Minor, a Christian named Carpus was nailed down to a stake to be burned. He laughed. When his persecutors asked why, Carpus said he had just seen “the glory of the Lord.” The fire was lit, and Carpus uttered a prayer and “gave up his soul.” A woman named Agathonike, one of the onlookers, said she saw also “the glory of the Lord.” She believed it was a call from heaven and “threw herself joyfully” upon the stake.

Though voluntary martyrdom was strongly condemned by the church, it speaks volumes for the early Christians’ confidence that martyrdom was the sure path to glory. This is no insidious form of works righteousness, but a simple deduction based on the plain language of the New Testament. The writer of Hebrews, in describing past martyrs, put it bluntly: “Others were tortured, refusing to accept release, in order to obtain a better resurrection.”

Jesus noted, “Brother will betray brother to death, and a father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death; and you will be hated by all because of my name. But the one who endures to the end will be saved” (Mark 13:12-13, NRSV). Or more simply still: ” … those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the gospel, will save it” (Mark 8:35).

The 70 crucified Japanese Christians—or to take modern martyrs like Paul Carlson or Jim Elliot—are assured of heaven not because of their martyrdom but because of their faith, which gave them courage to be martyrs. Martyrdom is simply the outward sign of that inward faith.

More important still, whether or not their deaths helped grow or strengthen or purify the church does not seem to be the concern. The point of honoring the effective and “ineffective” martyrs alike is that they today enjoy the presence of God.

This is especially important to remember in the case of severe persecution that destroys the church in a region. Rather than shun such history and sweep such instances into a dustbin of tragedy, we can look successful persecution in the face and say, with the New Testament and early church: “Ha!” For we know eternal freedom has been given those whose temporal freedom was stolen; eternal life was granted those whose life was taken. In short, martyrs remind us of the reality of heaven.

The cross in focus The early church teaches us a third lesson about martyrdom. W. H. C. Frend noted of the early martyrs, “They were seeking by their death to attain to the closest possible imitation of Christ’s Passion and death. This was the heart of their attitude. … The martyr was ‘a true disciple of Christ,’ one who ‘follows the Lamb wheresoever he goes,’ namely to death.”

The second-century author of the Martyrdom of Polycarp wrote, “We love the martyrs as disciples and imitators of the Lord, deservedly so, because of their unsurpassable devotion to their own King and Teacher.” Then he adds, “May it be also our lot to be their companions and fellow disciples!”

Again, the idea has its genesis in the New Testament. Paul said, “I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death, if somehow I may attain the resurrection from the dead” (Phil. 3:10-11, NRSV).

When we look at the martyrs whose stories we know—like that of the Ecuador martyrs—or those we can only guess at—like the silent Chinese martyrs who were slaughtered in the 800s—Jesus is immediately brought into focus. He was rejected and despised by others, yet he went to death willingly.

I’ve come to believe that God, in his wisdom, allows martyrdoms in every generation in part because, without them, the reality of Christ’s death for us becomes increasingly blurry. The martyrs, for those brief moments, look like our Lord on the cross. As we look at them, the mist that sometimes enshrouds first-century Golgotha is burned away, and we see with startling clarity the Lord nailed to the cross.

Whether a particular martyrdom actually does any practical good for the church does not matter. Whether we know the martyr’s name or history is not important. That we know the God who knows us knows them and that they are the ultimate imitators of Christ—that is what counts.

Redeemed by the blood Fourth, the early church believed martyrdom was a sacrifice for other Christians. Ignatius is the first Christian martyr (apart from the New Testament writers) who left us evidence of his state of mind before his martyrdom. Thinking of his impending death, he wrote to the church at Ephesus, “May my soul be given for yours.” He echoes Paul’s sentiments in 2 Corinthians 1:6: “If we are being afflicted, it is for your consolation and salvation.”

We do not have to posit some ontological transaction to grasp what these writers are talking about. There is a simple sense in which the martyrs redeem us.

In studying this topic, I often find myself picturing one of the thousands upon thousands of anonymous martyrs in China, in North Africa, and in central Africa today. I imagine the last minute of the last Christian, bound and dragged by authorities into some dreary courtyard in some distant village. This woman has been rejected by family and friends; no believer remains who can record this moment for others’ edification. This Christian is utterly alone.

Perhaps she looked desperately for a way out; perhaps she suddenly doubted whether all she believed was true; perhaps she broke down and wept. Perhaps she was on the verge of stamping on the cross or offering incense to the current Caesar or simply cursing Jesus—but she didn’t. And then she was hanged. Or perhaps shot. Maybe beheaded. Maybe crucified.

That sobering recollection blurs my eyes with tears; it also sharpens my sight. Once again I see Jesus hanging defenseless, rejected by family and friends, so alone he feels even God has deserted him. I see the nails puncturing his flesh, watch his body sag, and hear his resigned “It is finished.”

Something about that image always startles me, reminding me of the regular ease with which I compromise with the world. At the sight of this image, I repent again of my weak faith. And almost in the same moment I repent, I hear the words of Scripture reverberating within, “You are forgiven.” And before I begin going about my business again, I ask for at least some small measure of courage.

And so, once again, albeit ever so briefly, I am redeemed from bondage to self-centered cowardice—thanks to the martyrs, especially the ones who didn’t do any good.

Mark Galli is editor of CHRISTIAN HISTORY magazine, a publication of Christianity Today International.

Copyright © 1997 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.