One of the nation’s newest and fastest-growing Christian movements may also be among the most dangerous, say campus ministers and religion scholars.

“It’s the most destructive religious group I’ve ever seen,” says Robert Watts Thornburg, dean at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel, commenting on the International Churches of Christ (ICC), based in Los Angeles.

The ICC’s 10 percent-plus annual growth rate places it among the fastest-growing religious groups in North America. The church lists membership at 143,000 in 292 churches, including 34 congregations that have an average weekly attendance of at least 1,000. About 80 congregations are in the United States.

The movement is active in 115 countries, and one of its new goals is to plant a congregation in every nation with a city of at least 100,000 people by the year 2000. Hope Worldwide, the ICC relief-and-development agency, operates 100 projects in 30 countries.

Religion analysts contend that the ICC has run afoul of many Christian groups not only because of its assertive evangelism but also because it promotes the view that it is the “faithful remnant” church and because it makes a practice of rebaptizing Christians from other denominations.

ICC’s discipleship practices, which some former members say are coercive and controlling, have also been held up as an example of the church’s unacceptable extremism.

Yet Al Baird, an elder in the Los Angeles Church of Christ and the ICC’s top spokesperson, vehemently denies that the church abuses its followers. He maintains that the group’s intense focus on evangelism and discipleship is grounded in Scripture.

“As we look around us, the job of evangelizing the world is not getting done,” Baird told CT. “Jesus said to go and make disciples of all nations. God’s plan for accomplishing that is revealed in the Bible. We’re trying to be the church that follows that plan.”

The ICC’s extensive site on the World Wide Web (www.intlcc.com) states, “To our knowledge, we are the only group that teaches the biblical principle of discipleship as a necessary part of the salvation process.”

BU’s Thornburg remembers two new religious groups arriving on campus for the first time in the fall of 1979: the Unification Church and the International Churches of Christ.

In the nearly two decades since, Thornburg knows of a total of four students who have dropped out of school upon joining the Unification Church, founded by Sun Myung Moon. By contrast, as many as 45 students a year quit school after becoming ICC members, he reports.

Boston University banned ICC members from its campus a decade ago when they refused to stop door-to-door recruitment inside dormitories. At least 20 other schools, including Boston College, Marquette University, the University of Southern California, Georgia Tech, Vanderbilt, and Emory University, have barred the group or denied campus registration because of allegations involving manipulative recruitment or harassment of students. College-age students are an important constituency to the ICC. The Los Angeles ICC reports about 22 percent of 11,000 attenders are college students.

WHOLESOME EXTERIOR: Church members cultivate a clean-cut and friendly image. In fact, “love-bombing,” in which potential members are smothered with praise and attention, is one of the ICC’s trademark techniques.

“Nice is the word for these people,” Thornburg says. “When they’re recruiting, they are polite and respectful.”

Theologically, the group seems orthodox in many ways. And many consider the fervor and sincerity with which ICC members attempt to follow the Bible’s teachings to be admirable.

Yet those who leave the ICC—and there are many—say they do so confused, angry, and sometimes disillusioned with Christianity altogether.

According to Dawn Lynn Check of United Campus Ministry, which coordinates activities at three Pittsburgh campuses, members typically learn students’ class schedules, then wait outside to meet them. “It catches them off guard,” says Check, “and makes it harder for them to say no.” Check questions the ICC’s legitimacy partly because members do not fully identify themselves when they invite students to an activity.

Last year, according to Check, members set up a table at an activities fair on the campus of Carnegie Mellon University, even though the group is not an official campus organization. When Check asked them to leave, they refused.

BU’s Thornburg says, “Peer control is the most important force on college campuses, and peer control is this group’s most important weapon.”

CHURCH ROOTS: Kip McKean, the group’s 43-year-old founder, started the movement with 30 people in the Boston suburb of Lexington in 1979. Renamed the Boston Church of Christ, the congregation grew quickly and soon moved to the Boston Garden sports arena.

McKean grew up in a Methodist home, and made a commitment to Christ while a student at the University of Florida in Gainesville upon visiting one of the 13,000 independent Churches of Christ congregations. That 1.6 million-member denomination is distinctive for shunning instrumental music during worship. In 1987, the denomination severed ties with McKean’s group, which it has labeled as divisive, authoritarian, and dangerous.

McKean declined to be interviewed for this article, but in a 1992 interview with the Miami Herald he said, “We are not a cult. You don’t have to shave your hair and give all your money to the church. But you do have to give your heart. In our minds, we’re just trying to get back to the Bible.”

In 1990, McKean moved the headquarters to Los Angeles. Congregations typically meet in public facilities, and less than 2 percent of churches own their own buildings.

GOD’S TRUE CHURCH? The ICC’s claim to be the only truly Christian church is expressed in numerous ways.

Former members report that they were instructed that if they left the ICC, they would no longer be following Jesus. “If you walk away from the church, you’re leaving Jesus, and you absolutely lose your salvation,” says Baird, who has been in the movement since 1983.

He believes it is theoretically possible for a person outside the ICC to follow God’s plan as revealed in the Bible, but he says he has “yet to find another group that is living the lifestyle, being a light to the world, and going out and making disciples as Jesus taught us to do.”

The ICC’s contention that it alone follows God’s plan revolves around its distinctive views of how baptism and discipleship lead to salvation. The ICC teaches that a person is not saved until being baptized by immersion. This baptism, Baird says, constitutes the “culmination of the new birth.”

According to Eastern College theology and Bible professor Christopher A. Hall, traditional Christian doctrine regards salvation and baptism as a “package deal,” but it is not the baptism itself that accomplishes salvation. Hall adds, “I consider it heretical for any group to say that only its form of baptism is efficacious.”

New Testament scholar Craig Keener has debated and counseled ICC members on the Duke University campus and elsewhere. He says that Christians who have been baptized by immersion and who were living disciplined Christian lives have nevertheless been told by the ICC they had to be rebaptized in order to be saved. “Being baptized is not enough,” says Keener. “They teach that a person has to be baptized with the understanding that with baptism they are saved.” That is tantamount, Keener maintains, to saying that Jesus “is not fully adequate for salvation.” Baird believes his salvation was not complete until his second baptism in 1987, four years after joining the church.

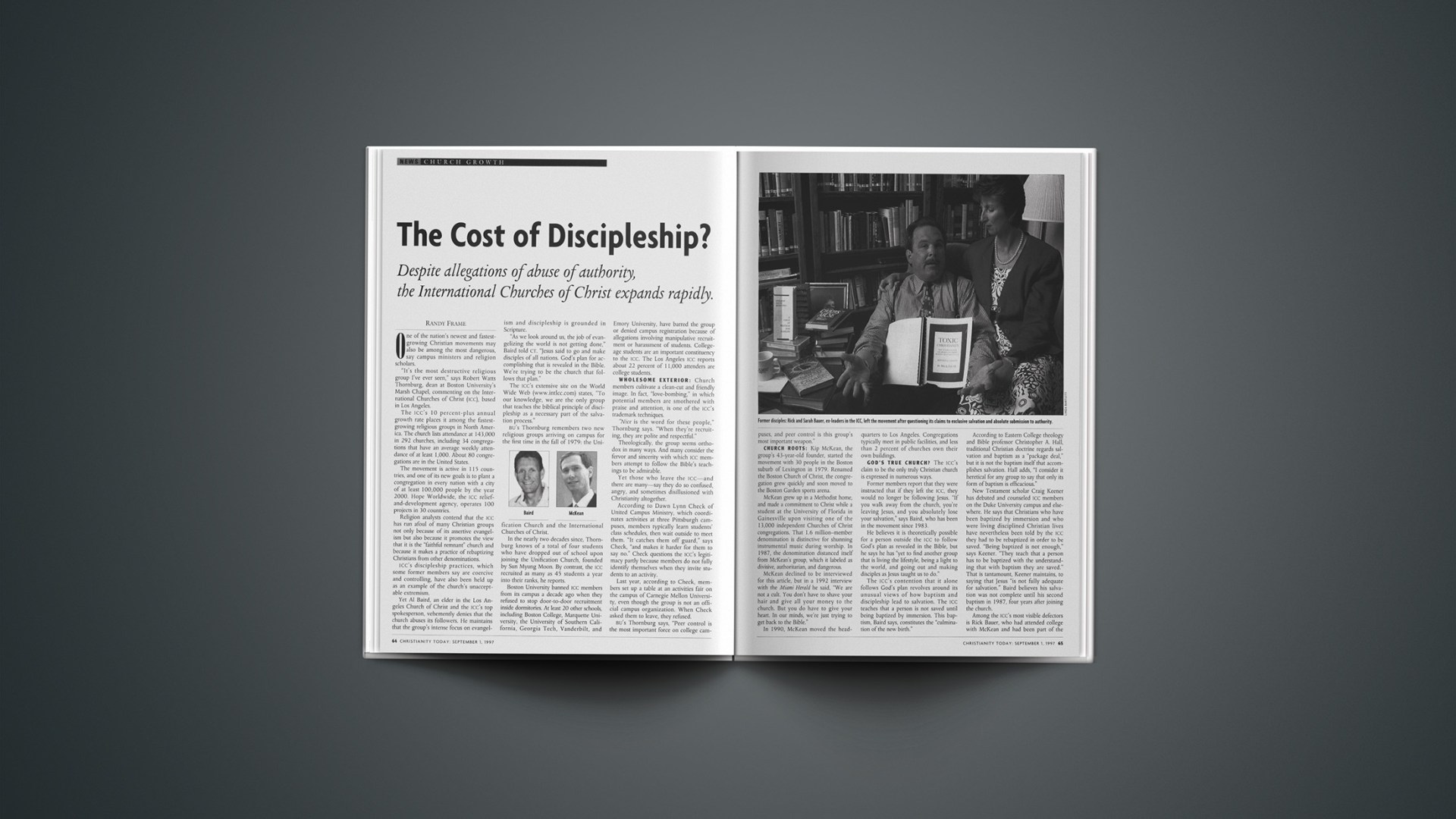

Among the ICC’s most visible defectors is Rick Bauer, who had attended college with McKean and had been part of the movement from its beginning before leaving in 1991. Formerly a high-ranking leader, Bauer was “discipled” by church founder McKean himself.

Bauer says the church sent him to Harvard Divinity School in the late 1980s to groom him as an apologist.

“The movement and I parted paths on a number of theological issues,” Bauer says. “I could not accept the view that it is the only visible representation of God’s church on earth.” In 1991, Bauer and his wife, Sarah, formed a ministry in Bowie, Maryland, called Freedom House Ministries, through which they counsel former and current members.

Bauer objects to the movement’s recruiting practices. “What they do is highly orchestrated,” he says. “They don’t say who they really are. They approach people saying they just want to sit and study the Bible.”

NECESSARY FOR SALVATION? The ICC teaches “the biblical principle of discipleship as a necessary part of the salvation process.” To qualify for baptism—and thus salvation—a person’s behavior undergoes rigorous scrutiny by local church leaders who look for signs of godly living.

This methodology leads religion researcher Joanne Ruhland of San Antonio to conclude, “Although they profess to uphold the orthodox tenet of salvation by grace through faith, in practice they deviate from that.” Ruhland has focused on the ICC for more than four years and has studied more than 200 sermon tapes of church leaders.

Ruhland says that to be a candidate for baptism, disciples must list and confess all their sins to at least one leader, study the Bible daily, share faith with others, and submit to authority. In most locations, she says, church attendance and tithing are considered mandatory.

According to Yun Kim of Santa Monica, California, who was involved in the ICC from 1994 to 1996, during the prebaptism discipleship period, “People are told they are not disciples if they are not out there making other disciples.”

Detractors say the emphasis on becoming a disciple as a prerequisite to salvation did not become part of church doctrine until 1987. Bauer recalls McKean saying that the new emphasis did not mean that “new truths were being revealed, but that old truths were becoming clearer.” As a result, church members—including those who had been discipled by McKean—had to be “rebaptized.” Bauer says he and a few others dissented, but to no avail.

Despite his questions about the ICC, Keener believes the religious world can learn from the movement.

“A lot of people after leaving have a hard time finding a body of believers that has the same level of intimate fellowship and commitment to God,” Keener says. “This is a tragic indictment of the church.”

According to Hall, it is precisely this high level of commitment that contributes to the group’s appeal. “Groups such as these tend to have some teaching that no other group has, a strong central personality, a high level of commitment, strong sense of discipline, and fear of the consequences of leaving.”

ABUSIVE CONTROL? In the late 1980s, research psychologist Flavil R. Yeakley, then of Abilene Christian University, developed personality profiles of 900 ICC members at the invitation of the movement and compared them with other religious groups.

He concluded, “The Boston Church of Christ is producing in its members the very same pattern of unhealthy personality changes that is observed in studies of well-known manipulative sects.” Yeakley said church members were influenced to “conform to the group norm.”

However, the ICC has countered Yeakley’s findings by reasoning that church members are being made “after the image of Jesus Christ.”

According to researcher Ruhland, it is common for some leaders to exert a strong influence on their disciples’ choices for everything from which college courses to take to the right marriage partner. “They advised me on every aspect of my life—when to go to bed, where to work, whom to date, whether to go on vacation,” former member Kim says. “And they labeled people strong or weak Christians based on who would fall into line.”

She finally left the group after being told by her discipler that she was “rebellious, proud, and arrogant” for not participating in a mandatory, weeklong fast called by a church leader. Those who challenge their discipler sometimes are told that they are being attacked by Satan.

Amy Cimino of Agoura, California, a church member from 1984 to 1992, says, “After I left, it took me a while to regain the mental capacity to make my own decisions.” Cimino began to consider leaving after she chose not to attend a late-night birthday party for a church member and her discipler accused her of “being rebellious and having a bad heart.”

Cimino says that when word began to spread that she was rebellious, she requested a meeting with a church leader to explain her perspective. But when she showed up for the meeting, she found not one but five leaders, all there to interrogate her. “It was an open time for them to talk about all the bad things I had done.” Former members say this is known as a breaking session, intended to intimidate individuals into conformity. As part of the session, they say members are reminded of the sins they confessed to earlier.

Tom Recchuiti, administrator at the Greater Philadelphia Church of Christ, maintains that he has never found the discipleship process abusive in his three years in the ICC. “If I’m given advice I don’t agree with,” he says, “I talk about it with my discipler. If we can’t resolve it, we’ll take it to a third person, like it says in the Bible to do. These options are open to all church members.”

Recchuiti remembers that when he was a graduate student he was taken aside by his discipler after he signed up for a class that conflicted with the church’s midweek service. “He showed me from the Bible that is important to meet with the body of believers,” Recchuiti says. “I realized I’d made a mistake, but he advised me to make the best of it and go ahead with the class.”

However, Ruhland says members are taught that their discipler is given to them by God, and obeying the discipler is a measure of spirituality within the group. Ruhland says McKean has taught that “discipling is God’s plan. It’s not a choice. You don’t get to vote on it. You can’t go halfway with it any more than you can go halfway in marriage.”

Baird maintains, however, that the church’s approach to discipling is merely to advise. “Discipling is nothing more than mentoring, using the experience of an older person,” he says. “That does not give a discipler the right to define right and wrong for another person.”

According to Baird, for a discipler to make decisions for others in such areas as which car to buy or which course to take or whom to date is “totally inappropriate.” He adds, “I’ve never heard of a mandatory fast. If I would, I would absolutely put a stop to it.” Baird acknowledges that there have been rare abuses through the years: “We don’t claim that this system is infallible.”

Westmont College sociologist Ron Enroth has taken the movement to task in his books Churches That Abuse and Recovering from Churches That Abuse. “Because they claim the tag evangelical,” Enroth says, “I’m concerned that they will cast a shadow on legitimate campus ministries.” Enroth cites the group’s tendencies to sever ties with familiar social support systems, especially the family.

Some have found fault with the church’s structure, under which each member is directly accountable to a “discipler.” Bauer says the ICC’s approach to discipleship has its roots in the shepherding movement, which has been widely discredited in evangelical circles.

Former members allege this structure results in regular patterns of spiritual and emotional abuse, as disciplers attempt to control the lives of those under them in the discipleship hierarchy. According to Ontario Theological Seminary professor James Beverly, “Life inside the various branches of the ‘only’ true church can be a nightmare as members are subjected to high-pressure programs that ensure complicity and uniformity.”

BREAKING UP IS HARD TO DO: While staying within the group can be difficult, thoughts of leaving can be equally distressing, former members report.

Cimino says, “I had this incredible fear that if I would leave the group, I would be helpless and lost.”

According to BU chaplain Thornburg, “Many people are unable to cope with stress, they can’t form relationships, they can’t focus on studies.”

Former member Michelle Campbell of Berkeley, California, left the ICC in 1994 after four years, but experienced so much fear and guilt that she tried to return. Her process of restoration, she says, included proving her remorse to leaders through daily prayer and acts of discipleship.

During this time, she says, she was not permitted to attend any church or to speak with church members. After she broke ties for good in 1996, Campbell says she sought counseling for depression. “They teach that if you leave the church, you’re leaving God.”

Copyright © 1997 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.