Each year during the liturgical celebration of the Passion, Christians relive the events of Christ’s last week on earth before his resurrection. To highlight this season, we showcase the work of seven contemporary artists who consider the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus anew with a variety of approaches.

Using a vibrant palette, Tanja Butler communicates the spiritual transaction underlying Jesus’ humble act of footwashing and, shown on the cover, Jesus’ last meal. The mundane is illumined with joy. In contrast, the subdued tones and foggy atmosphere of her Road to Emmaus (p. 47) create a gentle mood, suggestive of Christ’s everlasting patience as he waits for us to recognize him. Butler is a full-time printmaker and painter in rural upstate New York, a stepmother to nine children, and a lifelong Christian whose earliest childhood memories recall images from her parents’ illustrated Bible.

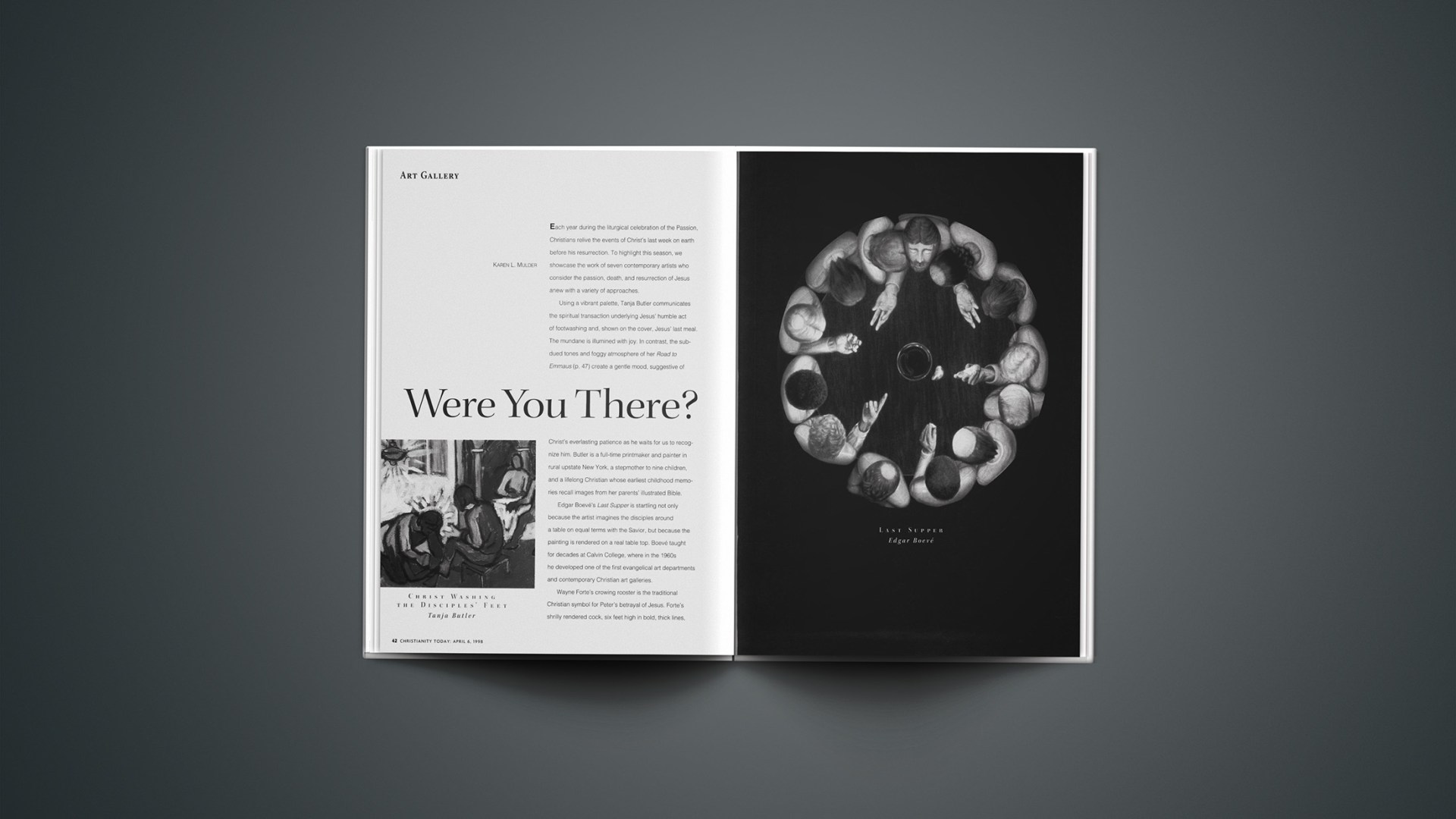

Edgar Boeve’s Last Supper is startling not only because the artist imagines the disciples around a table on equal terms with the Savior, but because the painting is rendered on a real table top. Boeve taught for decades at Calvin College, where in the 1960s he developed one of the first evangelical art departments and contemporary Christian art galleries.

Wayne Forte’s crowing rooster is the traditional Christian symbol for Peter’s betrayal of Jesus. Forte’s shrilly rendered cock, six feet high in bold, thick lines, reminds us of our continual propensity to fall short of the mark, as did Peter. Forte, a successful California artist from the Philippines, will soon relocate to Brazil.

Bruce Herman’s haunting works boldly portray the face of Christ under the burden of his sufferings. As they are partly inspired by self-portraits, they intimate that the Lord is sympathetic to our personal sufferings. The Crowning and The Flogging (shown on the table of contents) are from the book Golgotha, published by Gordon College, where Herman is professor and chair of a burgeoning art department.

Black Sun Crucifixion echoes the distortion and pain found in the Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grunewald’s sixteenth-century painting for a congregation of patients with skin lesions. Catling sees that fallen humanity is constantly dealing with its self-inflicted disfigurement and victimization—and that Christ’s acceptance of this agonizing part of the human experience reveals his true, tough love for us. A well-known sculptor and art professor, Catling lives near Los Angeles.

James Disney’s ethereal Christ is otherworldly—neither totally solid, nor spiritually wispy—but his resurrected presence recolors the landscape, cutting through darkness with a golden light. Disney, a full-time Lutheran pastor and self-taught painter, “plucks faces” from his church’s pictorial directory to depict Christ, emulating Renaissance painters who intentionally portrayed Jesus as an ordinary person to invite the viewers’ empathy towards him.

William Weber, an art teacher from Illinois, leaves us with the ineffable peace of Jesus in a figure reminiscent of a timeless icon out of past history, but his Christ is also a modern and expressionstically drawn figure. In this way, the artist affirms the fact that Jesus Christ is as timeless as his peace is everlasting.

Karen L. Mulder is assistant professor of art and art history at Union University and cofounder of Christians in the Arts Networking, Inc. To contact these artists, e-mail klmulder@buster.uu.edu or write K. L. Mulder, Union University, Jackson, TN 38305.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.