On the edge of the Amazon jungle in Peru, at a mission station called Yarinacocha, I waited with a few others to board a six-seater Helio Courier for a two-hour trip into the jungle. Rain and other complications had slowed us down. So we sat with the pilots in their “office,” a grimy little room that smelled like fuel oil, the walls plastered with maps, the workspace cluttered with radios, oil cans, dirty coffee mugs, and dog-eared log books. One of the pilots asked me, “If a plane is flying and there is a bird flying inside the plane, does it add weight?” Pilots love putting these kinds of questions to innocents like me who are unschooled in aerodynamics. I was saved when someone announced that we had been cleared for departure, and I never let on that I didn’t have a clue.

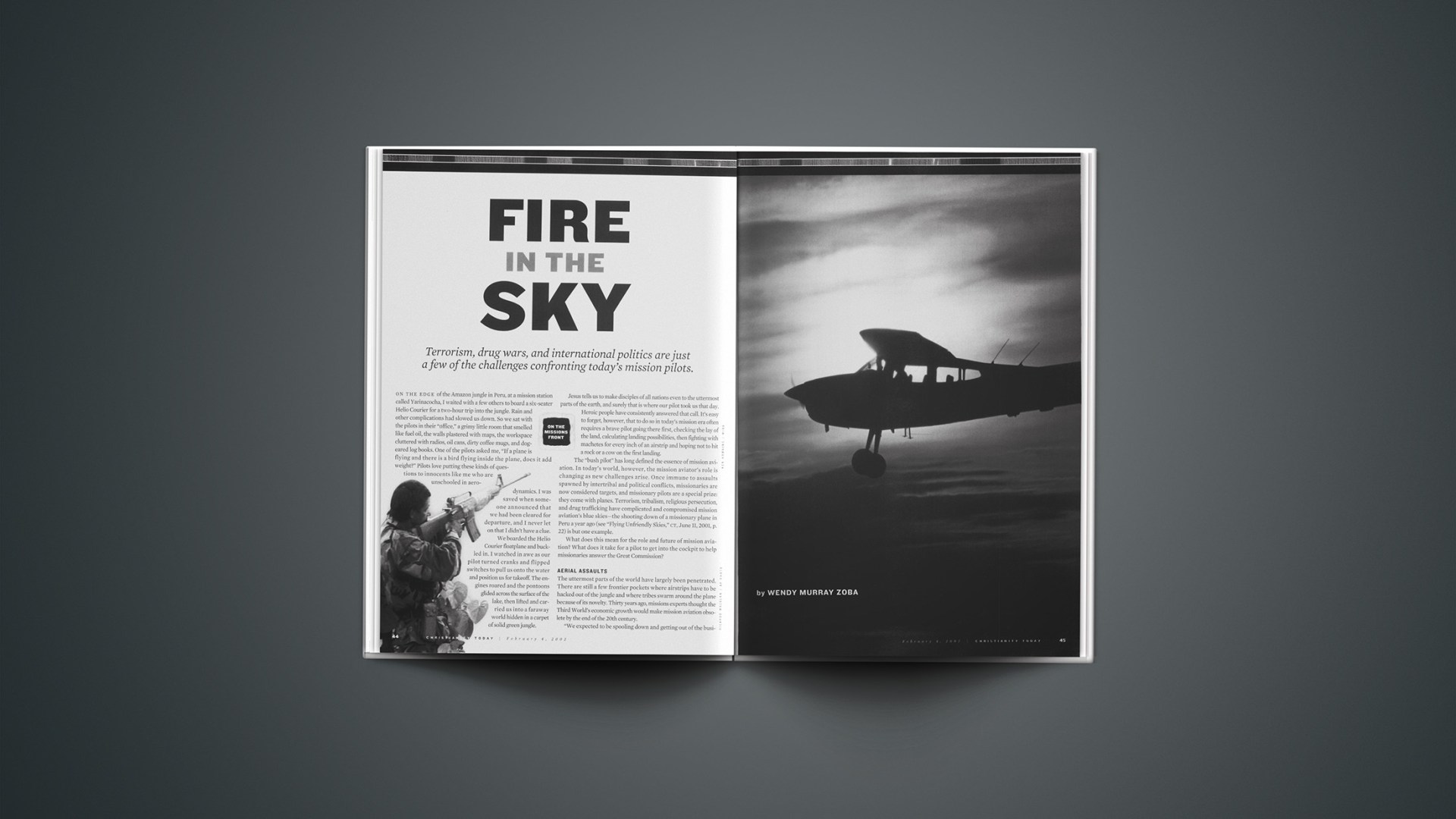

We boarded the Helio Courier floatplane and buckled in. I watched in awe as our pilot turned cranks and flipped switches to pull us onto the water and position us for takeoff. The engines roared and the pontoons glided across the surface of the lake, then lifted and carried us into a faraway world hidden in a carpet of solid green jungle.

Jesus tells us to make disciples of all nations even to the uttermost parts of the earth, and surely that is where our pilot took us that day. Heroic people have consistently answered that call. It’s easy to forget, however, that to do so in today’s mission era often requires a brave pilot going there first, checking the lay of the land, calculating landing possibilities, then fighting with machetes for every inch of an airstrip and hoping not to hit a rock or a cow on the first landing.

The “bush pilot” has long defined the essence of mission aviation. In today’s world, however, the mission aviator’s role is changing as new challenges arise. Once immune to assaults spawned by intertribal and political conflicts, missionaries are now considered targets, and missionary pilots are a special prize: they come with planes. Terrorism, tribalism, religious persecution, and drug trafficking have complicated and compromised mission aviation’s blue skies—the shooting down of a missionary plane in Peru a year ago (see “Flying Unfriendly Skies,” CT, June 11, 2001, p. 22) is but one example.

What does this mean for the role and future of mission aviation? What does it take for a pilot to get into the cockpit to help missionaries answer the Great Commission?

Aerial Assaults

The uttermost parts of the world have largely been penetrated. There are still a few frontier pockets where airstrips have to be hacked out of the jungle and where tribes swarm around the plane because of its novelty. Thirty years ago, missions experts thought the Third World’s economic growth would make mission aviation obsolete by the end of the 20th century.

“We expected to be spooling down and getting out of the business because of development,” says Ed Robinson, director of Moody Aviation, a premier flight-training school run by Moody Bible Institute and located in the mountains of eastern Tennessee.

Some locations, in fact, have “spooled down” and “gotten out.” Andy Halbert, former program manager for Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) in Honduras and pastor of administration and missions at Christ Covenant Presbyterian Church in Knoxville, Tennessee, oversaw the closing of MAF in Honduras. “Technology, the building of roads, and the advancement of the gospel have caused this era of mission aviation to end there,” he says.

Yet in other parts of the world, contrary to predictions, it is a different story. “When you look at certain places in Africa, the needs are greater now than they were 40 years ago,” says Robinson. “Today, in some locations there are only about 10 percent of the usable roads that were there in 1960.”

In Africa and many other corners of the world, the few roads that exist are rugged and riddled with bandits. “The back country is incredibly unsafe,” he says. “We hear horror stories about killings, lootings, rapes, and robberies.”

So, on one level, traditional mission aviation—taking up where the highways left off—is becoming less frequent. But the need for viable, safe, and expeditious transportation of mission personnel remains acute. And the approximately 600 pilots now serving mission agencies worldwide must adapt to a new world.

Terrorist activity, drug trafficking, religious persecution, and political instability complicate the picture. Says former Moody flight instructor Larry Tierney, “Today you might be living in Zaire and tomorrow it’s the Democratic Republic of Congo. You may have to evacuate two or three times.” JAARS (formerly Jungle Aviation and Research Service) closed its aviation program in Colombia in 1998 because of safety concerns, the first such closing in its history. JAARS pilot Mark Borland served there for ten years, transporting team members from Wycliffe Bible Translators. The civil war made flying extremely unpredictable and risky. Political groups on both ends of the spectrum, leftist rebels and right-wing paramilitaries, supported their efforts through kidnaping, extortion, and drug running.

“They were looking for airplanes and people to kidnap and ransom. It was very common to kill the operators to get the airplanes,” Borland says. He and his fellow Wycliffe pilots had an advantage: they flew Helio Couriers, which have the reputation of being difficult to fly. “Our airplanes weren’t as valuable because they knew they’d have to kidnap a pilot to go along with it.” Still, the dangers were ever present. He would communicate over the radio in code and look to trusted friends on the ground to signal when it was safe to land. “We did depend upon the Lord’s security there,” he says.

Jonathan Egeler serves with aim Air (Africa Inland Mission) and lived in Kenya and Tanzania for eight years before coming to Moody, where he teaches maintenance. “When I started with aim Air, we weren’t operating in any war zones. Now we’re operating in two or three at a time. You have to sign a waiver because insurance won’t cover operating in war zones.” I asked him what the greatest risks were for today’s missionary pilot: Getting shot down? Hijacked? Kidnaped?

“All of the above,” Egeler says. He has flown over southern Sudan where, he says, there’s “always a chance of getting shot down. We don’t have permission from the Khartoum government to fly into southern Sudan. It is held by rebels whom they’re actively fighting. But we have permission from the rebel forces to support their people there.

“I don’t think I ever heard it mentioned during my training that you might get shot at,” he says. “The thought was so remote, nobody had heard of it happening. But when I talk with students here, I do mention that they will probably have to fly somewhere wondering if they’re going to be shot at. That should be something they come to terms with on this end. That is where things are headed. We’re seeing more insecurity throughout the world, and mission aviation is part of that.”

“What does a pilot do if he or she is shot at?” I ask.

“Just keep going. Our planes are slow. If somebody on the ground is shooting at you, you have to keep going. If you’re on fire, well, then you have to put it down.”

Kevin Donaldson, the ABWE (Association of Baptists for World Evangelism) pilot who flew the Cessna in Peru, faced that scenario. Having been fired upon by the Peruvian Air Force, which mistook him for a drug runner, his plane was on fire, two passengers were dead, and he had no rudder control because his ankle was shattered by the gunfire (the rudder is operated by a foot pedal). He managed to land the plane on water without rudder control. Both wingtips hit the water and the plane could have easily spun around and flipped over. But he kept it under control and got the remaining passengers out.

Ed Robinson describes how in the 1970s, when he served first in the Philippines and later in Irian Jaya, warring tribes used to meet on the airstrips to fight one another. “It was an open area, and the warring villages could do their fighting. When somebody got hurt, they’d drag him to the missionaries for treatment. Today? Increasing numbers of our graduates haven’t facilitated evacuations of others so much as they’ve had to evacuate their own families. Their houses are looted and burned by the time they get back. And not just once—twice. Three strikes and you’re out. We bring them home.”

A Changing Flight Plan

The good news is that your typical missionary pilot doesn’t shrink back from such challenges. Larry Tierney worked for MAF for 20 years, 8 years as chief pilot on the field in Honduras. “There’s no doubt that the average missionary pilot has a little bit of cowboy in him,” he says. (I’ve heard Tierney, for instance, share stories about hunting and eating alligator while living on the Mosquito Coast of Honduras.) He quickly qualifies his comment: “But we try to make it boring, in the sense of being safe-boring.” I once flew through mountainous terrain with Larry, and after a soft landing on a grassy airstrip, I said, “Good landing.” He replied, “Any landing you walk away from is a good landing.” (He calls it “aviation humor.”)

The romantic image of the cowboy missionary pilot has its downside. Joe Hopkins, founder and president of Mission Safety International (MSI), says often a young man or woman will read a book like Jungle Pilot (a biography of Nate Saint by Russell T. Hitt) and catch a vision for mission aviation. “They come to Moody and put up with hassles and financial difficulties, but they have that goal,” he says. “They finish the training, face the obstacles of candidating with a mission agency, orientation, and raising support—but they have that goal. Finally, they get on the field. Then after they’ve been flying the same flights with the same people, they start noticing the problems and the hassles. They start thinking about coming home and giving it up. What’s really happened is that they’ve reached their goal but failed to set a new goal.”

A missionary pilot is “basically a glorified truck driver,” says Mark Borland of JAARS. “After you’ve hauled the umpteenth bucket of fuel up top of the wing, filtering it through, and rolling barrels around, it gets old pretty quickly.”

The tedium of the work has challenged the new breed of pilot trainees who are coming through the ranks. Some of the older, seasoned pilots and instructors at Moody are noticing a new mindset. “The Gen X people are very relational,” says Tierney. “They see their ministry in those terms. If they’re not getting their relational needs met, they begin to think, ‘What am I doing this project for?'”

For many, Tierney says, flipping switches and turning cranks to transport someone in West Africa who works for gold companies doesn’t satisfy. (Some host countries require mission aviation pilots to service national industries as part of the arrangement.) “These are some of the gut issues that go with a technical ministry, where you are often isolated from mainstream ministry,” he says.

The newer pilots also seem to lack long-term commitment. Says Tierney, “We’ve seen more turnover in mission aviation over the last few years than we did back when I started. ‘Long term’ for many is two years, which is hard because you spend so much time and money to train them.”

Hopkins believes it goes back to those frustrated expectations. “The missions are taking a realistic look at the investment it takes to get somebody out on the field,” he says. “They recognize they have to adapt. If they stay two or three terms [a term can consist of two to four years], that’s good. It’s a young man’s game anyway. They normally don’t want you flying after 60.” (Women also are joining the ranks of missionary pilots, though their numbers are small. Of approximately 80 students at Moody Aviation, 5 are women.)

Steve Compton is a young pilot in his second year at Moody Aviation, and he does not dispute Hopkins’s assessment. Still, he sees it less as a lack of commitment and more as being “open to God’s leading.” “A lot of people I’ve heard about here have gone from feeling called to mission aviation, to evangelism or church planting. They’re open to wherever God leads.”

Hidden Challenges

Kevin Swanson served with MAF for 16 years in Latin America, the last four as regional director, and now serves on MAF’s board. He says the key to equipping the new harvest of missionary pilots, and keeping them, is in the recruiting process. “You lay it all out and train young pilots in expectations,” he says.

Another more nuanced aspect to recruiting and training, Swanson adds, is to read your people. “You can take all missionary pilots and put them on this continuum,” he says. “At one end there are pilot-missionaries: they are highly skilled technicians with excellence in all things technical. They become the safety officers, the trainers, the ones who keep the rest of the organization honest.

At the other end are the missionary-pilots: they say the airplane is a good tool to get me out there where the ministry is. They’re the ones who’ll think, ‘Oh what’s a little rattle? We’ve got to get out there to show the Jesus film tonight.’ If the latter didn’t have the former, they would kill themselves,” he says. “You’ve got to figure out where your people fall on this continuum and then assign them appropriately, otherwise you’ll drive them crazy.”

Joe Hopkins credits Wycliffe Bible Translators for modeling an approach to ministry that has sustained its pilots over the long haul. “You ask a Wycliffe person what they’re about and the same answer comes back every time: Bible translation. Driving a truck, flying an airplane, turning a wrench, or working on a computer, their ultimate goal is Bible translation. Their goal is bigger than just flying an airplane. That keeps them challenged and motivated and willing to put up with the hassles.”

To sustain mission efforts, hundreds of pilots must be recruited every year. “They cannot produce enough pilots to meet the present demands,” says Swanson. MAF, for example, has 123 pilots and an immediate need for 30 to 40 more.

Recruitment, however, is not the only big need. Surprisingly, a critical issue facing mission aviation today—in the case of MAF—is availability of reliable aircraft. “The staple Cessna six-place airplane we’ve used for years and years isn’t so useful anymore,” says Swanson. “The ‘bush-pilot’ market was once big enough that they were willing to cater to it, but not anymore. Cessna has turned their airplanes into flying SUVs, when before they were flying pickup trucks, which is what we needed.”

Another obstacle is finances. “Mission aviation has never been cost-effective,” Swanson says. “The generosity of the U.S. church has always been the behind-the-scenes funding for mission aviation. If we were just serving the national church in a poor country, there is no way we could do it. This is a very expensive ministry.”

And given the changing circumstances under which pilots are flying, they need larger aircraft that can fly longer distances, which requires more money. Buying used Cessnas, like MAF has been doing, also requires a higher degree of maintenance, which also means more money. Add to that the expense of training new pilots who, as we learned, aren’t necessarily in it for the long haul, and the costs could rise even higher. As Larry Tierney told me, “You really need long-term commitment to get the most bang for your buck.”

The Flight Stuff

I wanted to know what kind of person it takes to be a missionary pilot in today’s world, so I asked some seasoned “cowboys” of the air.

One replied, “A person who understands himself correctly and doesn’t have any false conceptions about his capabilities.” Another said, “A patient person. You’re using technology to try to speed things up, but you’re operating in a Third World country where everything is there to slow you down.” Others pointed to someone who is flexible (“you have to be willing to get to know the culture of the people”), self-confident (so “you can make the right decision without a lot of reflection”), and teachable (“someone who is willing to take input from others”).

“You have to have a commitment to serve and a sense of calling—that will carry them through when the going gets tough,” says Joe Hopkins. Jonathan Egeler adds that a big part of a missionary pilot’s ministry involves encouraging others. “You’re in contact with missionaries in remote areas. You need to be able to get to know them, share prayer requests, and pray for and with them. That’s what really keeps you there.”

Kevin Swanson says that when it comes to risks, “The world hasn’t changed that much in the last 50 years. We’ve buried a lot of our friends. This has always been a risky business. If a person believes the Lord has directed them into this, then they need to count the cost.”

Before I left Tennessee, I asked Larry Tierney about the bird flying inside a flying airplane. “Does it add weight?”

“What is holding the bird up?” he asked.

“Its wings.” (Isn’t that obvious?)

“What is holding the wings up?”

“Air.”

“What is holding the air up?”

“The plane.” So, the answer is yes—in case you’re ever stuck in a hangar with missionary pilots who are waiting to see if it’s safe to fly.

Wendy Murray Zoba is a senior writer for CT.

Copyright © 2002 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere

Mission Aviation Fellowship‘s site has MAF-related news from around the world, an “e-mail a missionary” program, and other resources.

Africa Inland Mission‘s site has information and history of AIM Air and resources for missionaries.

Moody Aviation has information on the flight-training school, the curriculum, and a list of questions to ask yourself before choosing to be a missionary.

Jungle Pilot is available at Christianbook.com.

In August, a State Department and Government of Peru joint investigation team released its report (videophotos) on what led to the April 20 shooting of the missionary plane over Peru. The Washington Post article on the report included a transcript of what was heard over the plane’s radio.

Christianity Today articles on the tragedy include:

- Hot ZoneMissionary aviators say their risky work at times puts them in mortal danger. (May 8, 2001)

- Peru’s Churches Want Inquiry into Why Missionary Plane Was Shot DownChristian leaders lament “absurd, excessive use of force” that killed Roni Bowers and her infant daughter. (May 2, 2001)

- Missionaries Shot Down in Peru, Mother and Infant KilledThe Peruvian air force, acting on information from a CIA-operated surveillance plane, believed the missionaries were actually drug runners. (April 23, 2001)