Nearly a decade has passed since the American Family Association called on its members to boycott the Walt Disney Company, accusing the entertainment giant of having “gone from trusted friend to hostile foe.” The AFA was disturbed by offensive adult content in productions from some of Disney’s subsidiary companies (including Miramax Films and ABC-TV), and also Disney’s alleged support of the homosexual agenda. The Southern Baptist Convention, Focus on the Family and other Christian groups soon followed the AFA’s lead.

|

|

|

|

The impact that this boycott has had over the years is hard to quantify (although the recent attempt to oust CEO Michael Eisner indicates that all is not well in the Magic Kingdom). But it’s safe to say that the Christian community and Disney still don’t always see eye to eye when it comes to acceptable entertainment.

So it’s a bit surprising to see two new books with the words “Disney” and “gospel” in the title, especially one that is aimed squarely at the Christian market.

The Gospel According to Disney is Orlando Sentinel religion reporter Mark I. Pinsky’s second exploration of the moral values found in popular culture, following up his successful The Gospel According to The Simpsons. (See Pinsky’s CT stories on The Simpsons here.) The Disney book is a more sizable undertaking, however, as he examines over 30 Disney animated films spanning eight decades, from Snow White and Seven Dwarfs to last year’s Brother Bear.

The late Philip Longfellow Anderson, who was a minister in the United Church of Christ, has a narrower focus in The Gospel in Disney, looking only at the 18 animated films produced during Walt Disney’s lifetime. But Anderson also goes into greater detail on the animated anthologies from Disney (“Make Mine Music,” “Fun and Fancy Free,” etc.), and also finds life lessons in the characters of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. (It’s worth noting that Anderson’s book was originally self-published published in 1999; Augsburg Books has since picked it up.)

Different gospels

It’s important to note the different definitions of “gospel” in each book.

For Pinsky, who is Jewish, it’s “the Disney gospel,” which he describes as “a consistent set of moral and human values in these movies, largely based on Western, Judeo-Christian faith and principles. … Good is always rewarded; evil is always punished. Faith is an essential element—faith in yourself, and even more, faith in something greater than yourself, some higher power.”

That higher power, according to “the Disney gospel,” isn’t God, but most often providential magic. When Geppetto wants his puppet to become a real boy in Pinocchio, he adopts a prayerful pose beside his bed, but he’s appealing to a “wishing star,” and it’s a Blue Fairy that grants his request. Cinderella has a Fairy Godmother to help her get to the ball, and when evil forces put Snow White and Sleeping Beauty to sleep, both are awakened by a prince’s magical kiss.

Pinsky says Walt Disney’s decision to avoid traditional religion in his animated films “was in part a commercial one, designed to keep the product saleable in a worldwide market.” When the characters in his stories needed some outside intervention to get them out of a difficult situation, “magic, Disney apparently decided, would be a far more universal device to do this than any one religion.”

But that doesn’t discourage Anderson from finding messages from God in the Disney films, as he uses these stories as a springboard to discuss themes also found in the gospel of Christ (along with a few forays into the Old Testament), derived from his own “Disney sermons.”

“Jesus of Nazareth used allegories, anecdotes, illustrations to teach about the kingdom of God,” notes Anderson, who also believes Christians can find plenty of valuable content in these animated classics—”the loss of innocence, the cost of righteousness, vanity leading to disaster, sacrifice leading to resurrection—such are the recurring themes in these films.”

Anderson introduces each discussion with a relevant Scripture passage before going into a description of each film’s story and the life lessons that can be extracted from it, usually embellished with relevant anecdotes from real life.

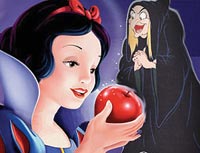

For example, Anderson sees parallels between Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, where the evil queen offers Snow White a seductive “wishing apple” (that’s really poisonous), and Genesis 3:1-7, where the serpent tempts Eve with a piece of fruit. But just as love’s first kiss provides the antidote for Snow White, God’s love expressed through Christ’s sacrifice can do the same for mankind.

Anderson’s other explorations are equally illuminating. Peter Pan’s shadow is equated with the influence each of us can have on the people around us, Bambi illustrates the beauty and fragility of creation, and Dumbo’s huge ears show that what we may first regard as a handicap can be a gift from God.

Each of Anderson’s chapters closes with some questions for family discussion after watching the film.

An analytical eye

In many ways, The Gospel According to Disney offers a similar approach, although with a more analytical eye rather than spiritual. Pinsky outlines the stories in detail, then points out the moral and theological themes that can be found in each.

Pinsky also explores the background of Walt Disney, whose opinions about organized religion were influenced by an authoritarian father, along with Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg, who were responsible for the Disney renaissance that began with 1989’s The Little Mermaid. He even touches on Christians’ clash with Disney in a chapter titled “The Baptist Boycott.”

Because the early Disney films had such a strong moral element, there aren’t many touchy issues to be dealt with. Pinsky does get fairly critical of the portrayal of American Indians in Peter Pan (even suggesting he would “fast forward through the whole repulsive village sequence”), and points out some controversy with perceived African-American stereotypes seen in the black crows in Dumbo.

However, the later material does get more problematic, particularly for Christian viewers, from the overtly occult elements in The Black Cauldron to the more subtle, Hindu-influenced “circle of life” philosophy of The Lion King. And then to top it all off, along came 1995’s Pocahontas, which found spirits in the trees and was criticized for ignoring the fact that the Native American heroine later converted to Christianity.

So what are we to do with Disney? Like all entertainment, it usually comes down to making wise choices, and these books can help in that process—whether or not to see them in the first place, what to look for if you do view them, and things to noodle on after the fact.

Of course, one could take the old AFA route and avoid them entirely, although personally I share Anderson’s belief, particularly with respect to the early Disney features. There is some classic storytelling in these old films, with ample opportunities to extract biblical truths while being entertained.

Mark Perry, a freelance writer and editor from Naperville, Illinois, is the former editor of PREVIEW Family Movie and TV Review, a newsletter that reviews entertainment from a Christian perspective.

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.