I have a confession to make. And although I know I am not alone in this sentiment, I am still a bit ashamed by it. OK, here it goes: As a child, I was terribly afraid of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971).

Many people say that Roald Dahl’s original children’s book, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, was meant as a children’s horror story—a dark Grimm’s Tale-like fable to scare kids into not being rotten, spoiled, overeating, gum-chewing, TV-obsessed little monsters. But I wasn’t spooked by the punishments suffered by the kids in the movie. Instead, I just found the movie—and Gene Wilder as Wonka—generally creepy, trippy and weird. I just didn’t get it.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve grown to appreciate Wilder’s darkly funny performance, his spot-on line delivery and the film’s whimsical fantasy. But still, I remember my fear of that bizarre little factory. With that said, it intrigued me to hear the new version of Dahl’s book would be directed by Tim Burton and star Johnny Depp, two guys with a bit of a resumé in creepy, trippy, and weird. And so, I viewed Burton and Depp as the two biggest wild cards in whether this movie would be any good.

It turns out that the duo has each succeeded in creating a fable that is not creepy or trippy, but just possessing a gentle weirdness (just wait for the scene with the “Small World” attraction) that is completely appropriate to Dahl’s original book. In fact, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a charming, engrossing, and often laugh-out-loud funny fairy tale that captures the book’s spirit while still marking its own territory.

Perhaps the best news is that Tim Burton didn’t make this movie 5 to 10 years ago. Burton, now a father, is apparently thinking a lot about fatherhood and family matters—and it shows. This is not the Planet of the Apes or Batman Returns Tim Burton. Or the Sleepy Hollow, Nightmare Before Christmas, or Beetlejuice Tim Burton. This is the Big Fish Tim Burton—a director who can weave a sweet, sentimental story in a wonderfully imaginative world akin to ours, but not.

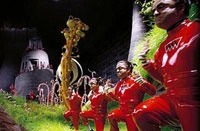

Burton directs a screenplay by John August (Big Fish, Charlie’s Angels, Titan A.E.) that is both very loyal and supplemental to Dahl’s book. For the most part, August’s screenplay follows the book page-for-page in its story about an eccentric chocolate maker who invites five lucky children into his factory for a tour full of imagination and lessons in humility and good behavior. This film, with its musical numbers performed only by Oompa Loompas, is much more direct from the book than the 1971 movie. In fact, the story includes several little bits from the book left out of the original film, including the Indian prince, Mr. Bucket’s job at the toothpaste factory, the children’s exit from the factory, and nut-shelling squirrels. Some of the kids’ bad habits are updated a bit, though. Mike Teavee now takes out his aggressiveness in violent video games instead of TV, and Violet’s vice isn’t just chewing gum but being a “driven young woman” who has trophies and championships in everything—including gum chewing.

Where August and Burton really change things up is with Willy Wonka (Depp). The chocolateer now has a back story to explain his career, his choice of solitude and his quirky personality. Roald Dahl was never happy with 1971’s Willy Wonka because he felt it focused too much on Wilder and his portrayal of Wonka—and not enough on Charlie (Freddie Highmore), the poor local boy who makes a special impression on Wonka. Burton reportedly had to convince Dahl’s widow to allow his film version, and one would think he had to pledge to focus more on Charlie. This is odd then that the film actually adds to Wonka’s character and fleshes him out in greater detail. But the new storyline doesn’t just increase Wonka’s presence. His back story, along with several new scenes at the very end, add a whole new theme: the importance of your family’s love (carried out in a way comparable to Big Fish). Thankfully, this new moral actually adds to Dahl’s warnings against greed, selfishness, anger and other vices to talk about how we truly become good, respectful, well-adjusted people: through the love and teachings of our parents and families.

The new storyline also dramatically changes Wonka’s character—as does the fact that he’s played by Johnny Depp. Probably one of the best character actors working today, Depp deals with the prospect of playing an iconic character by making the wise choice to not even go near what Wilder did. Wilder’s Wonka was an emotional, smooth and thrilling showman who may not have cared for the kids visiting his factory, but at least tried to act like it. Depp’s Wonka is an awkward, skittish, socially inept introvert who doesn’t even pretend to care if he doesn’t. He’s pale and almost greenish. He has a high-pitched voice and a lisp. In all, he comes off as a guy who’s been alone for many years—which he has been. He has to read off cue cards when he first meets his guests. He seems to be most amused by things in his own head. And he doesn’t understand manners or good appearances—and doesn’t try. In a way, Depp seems to play Wonka as a cross between a four-year-old and Dr. Evil.

For most viewers, Wonka’s new portrayal and the added storyline will determine if they appreciate the film or not. Some fans of Wilder’s Wonka won’t take well to Depp. And fans of the old movie and book may not like the added scenes. But they worked for me. In the preview commercials, I thought Depp’s Wonka seemed too odd and most likely annoying. But in the context of who the screenplay makes Wonka out to be—an awkward kid who is his own only friend and family member—Wonka’s childishness and eccentric quirks make sense. And the new storyline helps to not only explain Wonka but also to give Charlie a place to really shine and almost become Wonka’s peer as they both learn a bit about life, priorities, and what really makes people happy.

In fact, as fun as Depp can be, the film is really best when Charlie is in the driver’s seat, which is a tribute to both the writing and the amazingly captivating performance of Highmore. The scenes outside the factory are the best in the film: full of sweet charm and sincere emotion (thanks to Charlie and the whole Bucket family). The film’s only real downfalls are some slightly tedious and drawn-out factory sequences, including the new Oompa Loompa dance numbers. The film’s disappointing Oompa Loompas (all played by actor Deep Roy) use Dahl’s actual song lyrics from the book, but are largely unintelligible because the music is very fast, loud and rocking.

While some of the movie’s musical messages about naughty kids get lost, most of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory‘s pro-family, anti-naughtiness fable is still clear. However, I wonder if some small children may be unable to fully appreciate the film—much like myself with the original. But still, the movie is a funny and sweet adventure for kids and parents thanks to Burton’s ability to stir the imagination and tell a sweepingly charming story.

And thankfully, I don’t have to admit to being scared of this one.

Talk About It

Discussion starters

- Why do you think Willy Wonka is the way he is?

- Why did Charlie win? What made him different than the other kids?

- What do you think is the purpose of imagination? Why do people need it?

- What does Willy Wonka mean when he says “Family is not conducive to the creative process?” What is Willy’s problem with family?

- Charlie tells Willy that family is very important. Why do you think he says that? How is family important to you?

The Family Corner

For parents to consider

Rated PG for quirky situations, action and mild language. Children are put into perilous situations (like stuck in pipes, blown up like blueberries, etc.), but unlike the 1971 version, they are shown to be OK at the end. A father is also kicked down a hole. Wonka is often pretty weird and some of his actions may need explaining to small kids. He talks about cannibalism at one point. He also yells for a child not to touch a squirrel’s nuts, but that is the only anatomical joke or euphemism.

Photos © Copyright Warner Bros.

Copyright © 2005 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

What Other Critics Are Saying

compiled by Jeffrey Overstreet

from Film Forum, 07/21/05

“There is no place I know to compare with pure imagination.” Gene Wilder sang that dreamy refrain when he played Willy Wonka, the candy-making madman in the beloved but creepy 1971 film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, based on Roald Dahl’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

That famous song would fit in beautifully with director Tim Burton’s “take two” of Dahl’s whimsical adventure. Burton turns the story into an explosion of “pure imagination.” In fact, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is so alive with visual invention that some critics are saying there’s too much imagination on screen.

Fans will come away with mixed reactions. Burton’s version sticks closer to the original narrative, and young Freddie Highmore (Finding Neverland) is brilliant as Charlie. No one denies that Burton still has a knack for opulent spectacle. But the candy man has suffered yet another extreme makeover. In the 1971 film, director Mel Stuart transformed Dahl’s jumpy genius of junk food into a warm and endearing figure … and then put Wonka’s name in the title in place of Charlie’s. Johnny Depp, Tim Burton’s favorite leading man (Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood), plays Wonka as a somewhat-androgynous oddball with a much more elaborate back story than Dahl ever delineated.

Christian press critics have varying opinions, but most of them find the film a worthwhile confection with some substantial lessons.

Harry Forbes (Catholic News Service) calls it a “hugely inventive rethinking of writer Roald Dahl’s original work. Overall, director Burton’s take on the Dahl tale is predictably darker than the last version, and combines Dickensian atmospherics (though the setting is contemporary) with mordant wit.”

Steven D. Greydanus (Decent Films) says viewers will cry “with delight at all the film gets so magically right, and with frustration that in spite of that, the film is still nearly ruined by Burton’s obsessions and a spectacularly miscalculated performance by star Johnny Depp. No one but Burton could possibly have so perfectly nailed Dahl’s blend of whimsical fantasy and withering comeuppance, or the Dickensian glee and extravagance of its morality-play tableau, with abject poverty and decency lavishly rewarded while excess and surfeit and decadence are mercilessly punished.”

Steven Isaac (Plugged In) says, “The tone of the script owes more than a little to Wilder’s 1971 movie. … And it burrows deeper into the book and the stage play while it’s at it. An added bonus is that the special effects are super-cool, kid-friendly and positively hunger-inducing, and the Oompa-Loompas’ song-and-dance routines are a riot. All told, I’m sure author Roald Dahl, were he still with us, would be pleased. His playful morality tale is respected here, and the lessons he sought to teach arrive alive and kicking.”

Andrew Coffin (World) says the film’s “strong points mostly overcome the film’s weaknesses. One is Charlie himself—British actor Freddie Highmore, one of the best things about last year’s very good Finding Neverland. Another is Mr. Burton’s emphasis on the familial aspects of the story, staging wonderful scenes in Charlie’s poor but happy home. … This Charlie is a worthy improvement [on] the original film and a decent companion to Dahl’s book.”

Lisa Rice (Crosswalk) says, “The message of the movie is that the importance of the love and unconditional acceptance of a father cannot be overstated. And [the movie] does a fine job in making this theme clear. The production value is high, with some good acting, a brilliant music score, and some clever special effects.”

Mainstream movie critics turn in primarily positive reviews, while a minority finds Burton becoming more stylist than storyteller.

from Film Forum, 07/28/05

Peter Suderman (Relevant) says, “like his previous film, Big Fish, Burton’s eyes are too big for his brain, and his grandiose sets overwhelm the movie. Despite its gloriously realized, meticulously detailed world, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is marked by thin characters, stolid pacing and trite sentimentality. It’s all flashy color and puffed-up fluff, a cinematic cotton candy lacking in any real substance.”

Kevin Miller (Joy of Movies) says, “In terms of my childhood influences, Roald Dahl occupied the same rare air as J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and Dr. Seuss. … Needless to say, then, when someone like Tim Burton ventures to bring a book like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to the big screen, for me and countless other former children, he is treading on holy ground. Thankfully, even though Burton’s account of the gospel of Wonka is eerily unorthodox, he avoids falling into full-blown heresy. I wouldn’t necessarily call the changes he has made to the story improvements, but Burton’s film is definitely an intriguing adaptation of Dahl’s beloved children’s tale.”

Andrew Coffin (World) says, “Mr. Burton’s visual style is perfect for Charlie, and he rarely gives in to his more grotesque impulses (although smaller kids might be frightened). This Charlie is a worthy improvement on the original film and a decent companion to Dahl’s book.”

Denny Wayman and Hal Conklin (Cinema in Focus) conclude that it’s “a masterpiece of fantasy and morality. … Like all fables with clear moral instruction for children and adults, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is a worthy tale to be told to all.”

from Film Forum, 08/04/05

Josh Hurst (Reveal) says, “The most startling thing about Burton’s film is that, unlike many of his other movies about misunderstood geniuses, this one gives no excuses for self-indulgence and irresponsibility. Like the central character in Burton’s Big Fish, Willy Wonka is a man who has retreated to his own created world of fantasy, and with his seclusion he has forgotten how to show others compassion and love. His life is fractured because of his tormented childhood, and he carries with him a cold disdain for any and all grown-ups—particularly parents. But rather than make a hero of this man, as he did in Big Fish, Burton instead shows us what a lonely road Wonka walks, pointing us to the more excellent path of love, forgiveness, and family.”