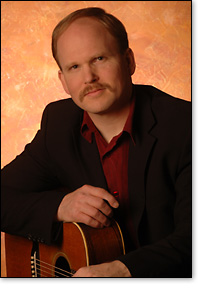

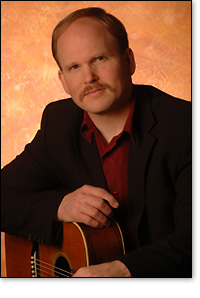

A winner of 13 Grammy Awards for his musicianship and songwriting, Ron Block is an unlikely premier bluegrass guitarist and banjo player. He first was attracted to the art form as a teenager in California, but later brought his own style to Alison Krauss and Union Station, with whom he has been a member since 1991. But his place in the band as well as his sanity were threatened in the mid 1990s, when he lost faith in the talent on which he had built his identity. He reflected on that dark period for our interview, while also discussing his second solo album DoorWay, influenced as much by C.S. Lewis and George MacDonald as by Bill Monroe and Lester Flatt.

How did a kid who grew up in Los Angeles come to love bluegrass?

Ron Block I worked at my dad’s rock ‘n’ roll music store. I had gotten an acoustic guitar in 1975 and played all the time, but then I picked up a banjo and just fell in love with it. I was thrilled with the sound of bluegrass. I also think it was a way to rebel. In the ultimate sense, it was God calling. If I had played rock ‘n’ roll, the path would have been much different than the one I’ve been on.

What has that path been like?

Block I grew up with a low sense of self-worth, and saw God as this distant, kind of stern figure. I was always trying to please him but felt I never measured up. One night as a teen, I was sitting in a car with a friend I was in a band with, and I remember him saying, “Ron, we’re not saved by doing; we’re saved by trusting God.” That was a huge epiphany for me. I went home and it was as if I had a whole new Bible. I began to look at the Bible as promises rather than commands. I learned from Matthew 6 that God would take care of my needs if I put him first.

But my identity was still wrapped up in being a musician. My attitude was, “I’ll work five times as hard and become great at this.” This identity track continued to escalate through my teens and early twenties. When Alison [Krauss] and the guys asked me to join in 1991, my sense of worth reached an all-time high—they were very vocal with their praise. But when you’re hooked into an identity source that’s rooted in the world’s system of performance-based acceptance, it’s going to fluctuate, and your self-concept is going to flop up and down with it. That high feeling I had was just the top of the roller coaster; in a short time it started to head straight down to the rocky bottom where the track suddenly ended.

What happened then?

Block God started to deal with the false identities I’d created from childhood. Around 1992, I prayed a Tozer prayer: “Lord, work your will in my life no matter what the cost.” God took that and ran.

One of God’s ways to break me was through my high standards [and perfectionism] in the studio. It was always, “Let me play that part one more time … Oh, that note was a little flat, do it again.” I began to believe I was no good and that I couldn’t play or sing at all because I couldn’t do it perfectly.

My perfectionism was kicking into high gear, and it was killing me. My perceptions and false beliefs—and through them my actions—were completely whacked out. As my sense of musical worth fell, I wasn’t Mr. Nice Guy anymore; all kinds of bitterness and resentments started coming up. It’s a tribute to how much the group loved me and loved the way I played that I’m still in the band.

What brought you out of that?

Block I’ve always known the Bible has the answers—I’ve read it since I could read—so I started digging through it. I started finding out about my identity in Christ, who I am in him, and who he is in me. I’d never paid much attention to verses like that before, but when you’re desperate and you think you’re a wretched person, they’re really powerful. So for several years, I was being transformed by this renewing of my mind, and I came out on the other side a different person. That was my second major epiphany, and again the Bible took on a whole new layer of meaning.

How are you different from the person you were before?

Block Previously, I wasn’t as outgoing or gregarious; more self-conscious and self-absorbed. Now I consider myself an extroverted introvert. I love talking with others about things, eternal and otherwise, and people are much more important to me.

I’ve learned that I no longer have to compare myself to anyone else. All I’m called to do is what God has called me to do. There’s a freedom in not worrying that I’m not as good as [so-and-so]. I still work on improving, but it’s coming from a different source. It doesn’t come from a fear-based place of not being good enough. I just want to be the best me I can be. As a result, I’m having much more fun on stage, and playing more freely.

Bluegrass is a very traditional form, but in a speech several years ago you emphasized the importance of continuing to innovate. How does an artist do that in bluegrass today?

Block When I was developing musically, I was trying to play just like Earl Scruggs or J.D. Crowe. I got to the point where I realized I can’t sound like them. I don’t have their personality, their hands, or their life history. I can imitate them, but it’s still only going to be an imitation. It’s not going to be the real deal. I still study the music of others and learn from it, but I’ve got to bring who I am into the music.

It’s the same way in the Christian life. We can try by effort to imitate Jesus, but that just brings you to the point where you realize the impossibility of it. Recognizing the impossibility leads you to say, “Well, Lord, I’m not going to lift a finger to be more like you. I’m going to trust you to live through me and use my talents and my personality.” When we’re living in him and through him by inner reliance, we are becoming more ourselves than ever. The normal Christian life is meant to be one of freedom and spontaneity, but we don’t find that until we throw away all our false self-concepts and take up our real selves in Christ.

What is it about songs like “Man of Constant Sorrow,” covered by everyone from Rod Stewart to Alison Krauss—and a hit on the O Brother, Where Art Thou soundtrack?

Block In our band, we do a ton of sad songs—songs of lost love, desperation, and loneliness. I think they put people in touch with how they feel. What’s funny is these songs are negative in terms of bad circumstances, but people go away from the concert glowing and joyful because the music gets them in touch with the heart.

What about the notion that Christians should only listen to positive music?

Block I can’t abide by that. I don’t think we can quarantine negative aspects of things and put them off in the corner and then say we’re only going to listen to something “spiritual.” Real life will have sorrow. Jesus dealt with that all the time. We can’t have the Resurrection without Gethsemane and the Crucifixion. If we took the same attitude with the Bible, we’d only have about a third of the book to read. It doesn’t work that way.

You seem at ease sharing musically about struggles with belief.

Block You have to put your own humanness out there. What makes any of us able to help others is our common humanity, our temptability. Jesus was human, tempted in every way, as we are. That’s what makes him our kinsman, qualified to redeem us.

What do you hope people will take away from DoorWay?

Block Having gone through my “spiritual crash” in the mid 1990s and then coming out of it, I have a burning passion for God’s people to know who they are. Paul never talks about behavior without pointing to identity first: “You’re a temple; be that … You were darkness, now you’re light in the Lord; be that.” Our real identity is in our union with God. Understanding and abiding in that union relationship keeps us from legalism and other forms of sin. That’s what I want for God’s people.

You have said that C.S. Lewis and George MacDonald have been major influences for you. How so?

Block I think I was eight years old when I read the Chronicles of Narnia. Years later, I read where C.S. Lewis said George MacDonald baptized his imagination—it was in MacDonald’s book Phantastes where he first encountered holiness and goodness. For me it was the Narnia books, and after reading those in my early years, I began to read almost everything Lewis wrote. Mere Christianity, Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, Till We Have Faces— all of that stuff I’ve read and re-read and worn out. After I had gone through a lot of those over and over, I started going through MacDonald’s work. Other inspirations have been A.W. Tozer, A.B. Simpson, Norman Grubb, Dorothy Sayers, and lately William Law and Jeanne Guyon.

How did Lewis’ use of doorways inspire you?

Block “DoorWay” [the song] came really quick, and I didn’t realize the connection when I was writing the song. The image of a freestanding door popped into my head, where it’s in the middle of a beautiful field. But the door is open, and on the other side is the desert and you can see into a whole different place. I had that image in my mind, but didn’t think about it until after I was done with the song when I realized the Wardrobe [in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe] was a doorway. Lewis uses doorways in Prince Caspian and The Last Battle as well. And MacDonald uses the image of a doorway in Lilith, a mirror that’s a stepping off point into another realm.

Can you picture Lewis sitting back in his study and listening to bluegrass?

Block (laughing) Probably not. In 2005, I got to go to the pub in Oxford where he hung out with Tolkien and the Inklings. The Inklings’ Room is very small; it must’ve been mighty close and smoky in there with all those literary geniuses.

Click here to read our review of Ron Block’s second solo album, DoorWay. To listen to song clips and buy his music, visit Christianbook.com

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.